The face of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) is changing. It has a dichotomous nature, with 1 subset of the disease associated with tobacco and alcohol use and the other having proven association with human papilloma virus infection. Imaging plays an important role in the staging and surveillance of OPSCC, and a detailed knowledge of the anatomy and pitfalls is critical. This article will review the detailed anatomy of the oropharynx and epidemiology of OPSS, along with its staging, patterns of spread, and treatment.

Key points

- •

Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) has a dichotomous nature with 1 subset of the disease associated with tobacco and alcohol use and the other having proven association with human papilloma virus infection.

- •

Imaging plays an important role in the staging and surveillance of OPSCC.

- •

A detailed knowledge of the anatomy and pitfalls is critical.

- •

This article reviews the detailed anatomy of the oropharynx and epidemiology of OPSCC, along with its staging, patterns of spread, and treatment.

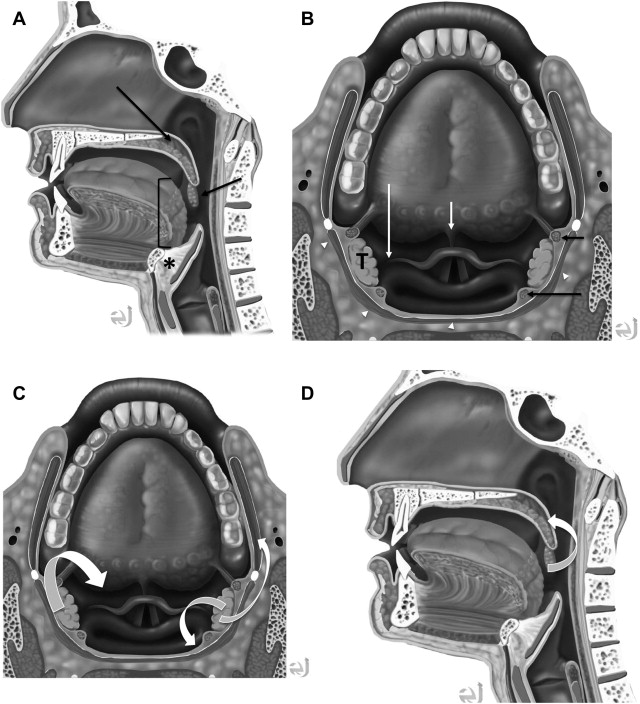

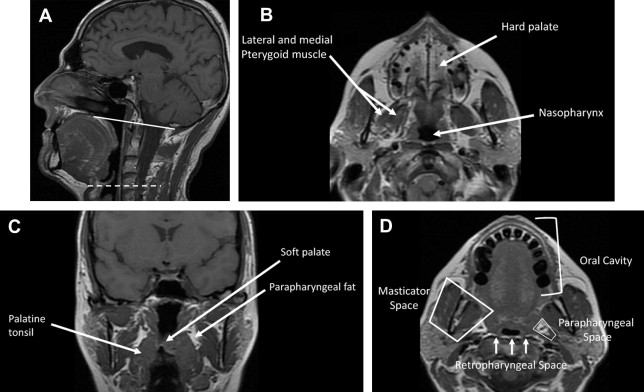

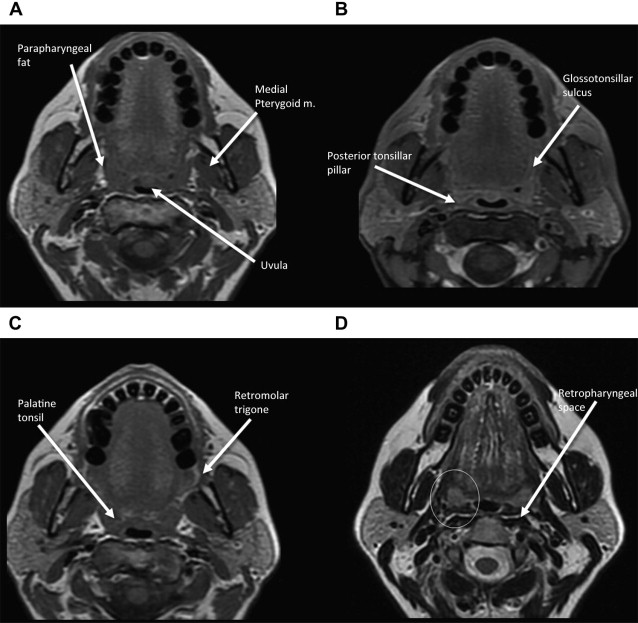

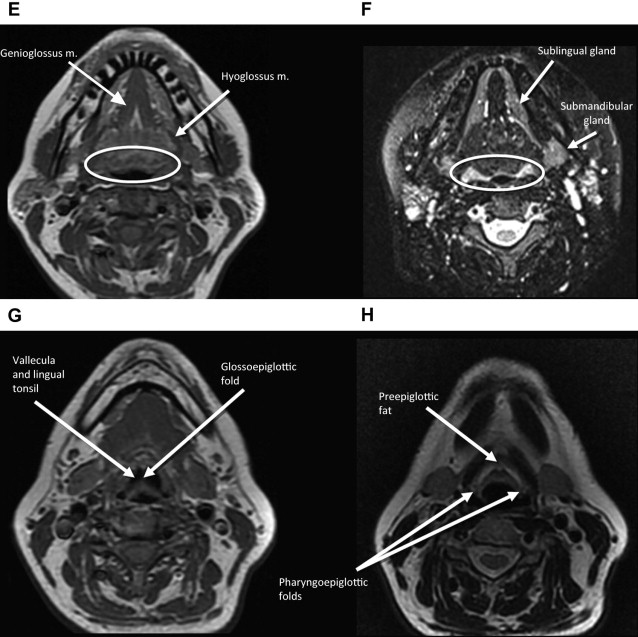

Anatomic extent of disease is central to determining stage and prognosis, and optimizing treatment planning for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). The anatomic boundaries of the oropharynx (OP) are the soft palate superiorly, hyoid bone, and vallecula inferiorly, and circumvellate papilla anteriorly. The OP communicates with the nasopharynx superiorly and the hypopharynx and supraglottic larynx inferiorly, and is continuous with the oral cavity anteriorly. The palatoglossus muscle forms the anterior tonsillar pillar, and the palatopharyngeus muscle forms the posterior tonsillar pillar. The OP has 4 subsites:

- •

Base of tongue including pharyngoepiglottic and glossoepiglottic folds

- •

Palatine tonsils including tonsillar fossa and anterior and posterior tonsillar pillars

- •

Ventral soft palate including the uvula

- •

Posterior and lateral pharyngeal walls at the oropharyngeal level

Contents of the OP include mucosa, lingual and palatine tonsillar lymphoid tissue, minor salivary tissue, constrictor muscles, and fascia. The overwhelming tumor pathology is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), arising from the mucosal surface. As the OP contents include lymphoid tissue and minor salivary glands, lymphoma and nonsquamous cell tumors of salivary origin can occur.

In understanding spread of disease from the OP, it is helpful to remember the fascial boundaries subtending the OP, to recall the relationship of the pharyngeal constrictor muscles with the pterygomandibular raphe and the deep cervical fascia, and to be aware of the adjacent spaces and structures. In staging of OP lesions, extension of malignancy to the larynx (but not the lingual surface of the epiglottis), oral cavity, masticator space, nasopharynx, and skull base or tumors with internal carotid artery encasement upstage the disease, regardless of tumor size. Note that mucosal extension to the lingual surface of the epiglottis does not constitute invasion of the larynx.

The OP is bounded deeply by the middle layer of deep cervical fascia (buccopharyngeal fascia), which is deep to the middle and superior constrictor muscles. The superficial (mucosal) surface of the OP is not bounded by fascia. To attach to the skull base, the superior constrictor muscle attaches to the pharyngobasilar fascia. The buccopharyngeal fascia is deep to the pharyngobasilar fascia. Tumors can potentially spread along the muscle and fascial routes from the OP to the skull base.

The middle pharyngeal constrictor muscle is connected with the buccinator muscle via the pterygomandibular raphe, which extends from the posterior mylohyoid line of the mandible to the hamulus of the medial pterygoid plate. This connection provides a potential route of tumor spread between the OP and the OC, between the OP and the central skull base (sphenoid bone), and between the OP and the pterygoid muscles in the masticator space ( Figs. 1–3 ).

Epidemiology

SCC accounts for 95% of neoplasms arising in the OP, and OP cancers represent over 50% of all head and neck cancers in the United States. Annually, 5000 OP cancers are newly diagnosed. The proportion of HNSCC arising in the OP increased from 18% in 1973 to 32% in 2005. Minor salivary tumors (adenomas/adenocarcinomas), lymphoid lesions (including lymphoma), undifferentiated malignancy, and sarcomas make up the balance of the tumors arising in the OP. While overall incidence of other HNSCCs has been declining since the 1980s, the incidence of OP SCC has been stable or increasing. Decline in smoking is the reason for the decline in overall numbers of HNSCC, while human papilloma virus (HPV)-associated malignancy explains the increase in otopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC), particularly in younger patients.

OPSCCs occur most frequently in men over the age of 40. Tumors are often insidious, growing in an infiltrative pattern, clinically silent until reaching a large size. The base of the tongue lacks pain fibers, and tumors in this location are often asymptomatic until quite large. Symptoms vary from site to site, but most commonly patients complain of throat discomfort. Small lesions can present as painless ulcerations. When the lesions are larger, the local extent is greater, and/or metastatic adenopathy is present, patients may complain of difficulty swallowing, ear pain, trismus, or neck mass from metastatic adenopathy.

Alcohol abuse and tobacco use, in a dose-dependent fashion, together and independently, are associated with increased incidence of OPSCC. Alcohol abuse has been found to potentiate the cancerous effects of tobacco exposure in the OP. In fact, it has been reported that synergistic action between alcohol and tobacco could increase relative risk of HNSCC by as much as 30-fold. Other factors implicated in the development of OPSCC include: history of SCC of the head and neck in a first-degree relative, history of cancer in a sibling, history of oral papillomas, poor oral hygiene, regular marijuana use, heavy tobacco use (20 pack–years or more), or history of heavy alcohol use (15 drinks or more per week for 15 years or more). Other risk factors identified for development of OPSCC are: a diet poor in fruits and vegetables, drinking mate, a brewed herb, and chewing betel quid.

In developed countries, OPSCC makes up 15% to 30% of head and neck cancers. In the past 25 years, the incidence of OPSCC has increased in the United States, Scandinavia, Canada, Netherlands, and Scotland in spite of stability or decline in overall HNSCC incidence. Three percent to 9% of OPSCC in these countries occurs in patients denying a history of tobacco/alcohol exposure, especially in young patients (10% to 30% nonsmokers and nondrinkers). HPV exposure and infection are responsible for the rise in OPSCC in western countries. Of the HPV-associated HNSCC, over 90% of cases arise in the OP and most commonly in the palatine tonsil, followed distantly by the lingual tonsil/base of tongue. HPV-negative tumors, on the other hand, are found in all subsites of the OP. HPV-associated tumors represent a separate subset of OPSCC with unique epidemiology, etiology and biologic characteristics, and prognosis.

HPV is an epithelliotropic DNA virus that primarily infects transitional epithelium that is found in the upper aerodigestive tract and anogenital regions. Over 120 different HPV types have been identified, but the subtypes implicated in OPSCC include HPV-16, 18, 31, 33, and 35, with HPV-16 identified in approximately 90% of HPV-positive tumors. The malignant potential of the HPV infection lies in the expression of viral oncoproteins E6 and E7; which, in turn, are able to inactivate 2 human tumor-suppressor proteins, p53 and pRb.

HPV is predominately a sexually transmitted disease, and infection is an independent risk factor for development of OPSCC. Its association with the development of cervical cancer and other anogenital malignancies is well known. People with HPV-16 oral infection are at a 15-fold higher risk for OPSCC and a 50-fold increased risk for HPV-positive HNSCC. As reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2007, lifetime number of vaginal sex partners of 26 or more was associated with development of OPSCC; so too was a lifetime number of oral-sex partners of 6 or more (with a 9-fold increase in relative risk). Synergy between tobacco and alcohol abuse/use and HPV infection with increased odds of OPSCC was not found.

HPV-positive OPSCC patients have been found to have significantly better outcomes as compared to HPV-negative patients, with a 28% lower risk of death than the HPV-negative patients. Also, nonsmoking patients with HPV- positive tumors have better disease-specific survival rates as compared with smokers with HPV-positive tumors. Black patients with head and neck cancer live significantly shorter periods after treatment than white patients, at least in part due to the fact that the black population in the United States has dramatically lower rates of HPV infection than Caucasian population. HPV status directly correlates with the significant survival disparities between the 2 patient groups. When survival is compared between black and white HPV-negative patients, survival is similar.

HPV-positive tonsillar cancers have been shown to have a lower number of chromosomal alterations as compared to HPV-negative OPSCC. HPV-associated OPSCCs are more likely to be undifferentiated and have basaloid histology and more frequent nodal metastasis. HPV-negative tumors, in contrast, have keratinized rather than nonkeratinized histology. Improved overall and disease-free survival after surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy have been reported in HPV-positive OPSCC.

Epidemiology

SCC accounts for 95% of neoplasms arising in the OP, and OP cancers represent over 50% of all head and neck cancers in the United States. Annually, 5000 OP cancers are newly diagnosed. The proportion of HNSCC arising in the OP increased from 18% in 1973 to 32% in 2005. Minor salivary tumors (adenomas/adenocarcinomas), lymphoid lesions (including lymphoma), undifferentiated malignancy, and sarcomas make up the balance of the tumors arising in the OP. While overall incidence of other HNSCCs has been declining since the 1980s, the incidence of OP SCC has been stable or increasing. Decline in smoking is the reason for the decline in overall numbers of HNSCC, while human papilloma virus (HPV)-associated malignancy explains the increase in otopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC), particularly in younger patients.

OPSCCs occur most frequently in men over the age of 40. Tumors are often insidious, growing in an infiltrative pattern, clinically silent until reaching a large size. The base of the tongue lacks pain fibers, and tumors in this location are often asymptomatic until quite large. Symptoms vary from site to site, but most commonly patients complain of throat discomfort. Small lesions can present as painless ulcerations. When the lesions are larger, the local extent is greater, and/or metastatic adenopathy is present, patients may complain of difficulty swallowing, ear pain, trismus, or neck mass from metastatic adenopathy.

Alcohol abuse and tobacco use, in a dose-dependent fashion, together and independently, are associated with increased incidence of OPSCC. Alcohol abuse has been found to potentiate the cancerous effects of tobacco exposure in the OP. In fact, it has been reported that synergistic action between alcohol and tobacco could increase relative risk of HNSCC by as much as 30-fold. Other factors implicated in the development of OPSCC include: history of SCC of the head and neck in a first-degree relative, history of cancer in a sibling, history of oral papillomas, poor oral hygiene, regular marijuana use, heavy tobacco use (20 pack–years or more), or history of heavy alcohol use (15 drinks or more per week for 15 years or more). Other risk factors identified for development of OPSCC are: a diet poor in fruits and vegetables, drinking mate, a brewed herb, and chewing betel quid.

In developed countries, OPSCC makes up 15% to 30% of head and neck cancers. In the past 25 years, the incidence of OPSCC has increased in the United States, Scandinavia, Canada, Netherlands, and Scotland in spite of stability or decline in overall HNSCC incidence. Three percent to 9% of OPSCC in these countries occurs in patients denying a history of tobacco/alcohol exposure, especially in young patients (10% to 30% nonsmokers and nondrinkers). HPV exposure and infection are responsible for the rise in OPSCC in western countries. Of the HPV-associated HNSCC, over 90% of cases arise in the OP and most commonly in the palatine tonsil, followed distantly by the lingual tonsil/base of tongue. HPV-negative tumors, on the other hand, are found in all subsites of the OP. HPV-associated tumors represent a separate subset of OPSCC with unique epidemiology, etiology and biologic characteristics, and prognosis.

HPV is an epithelliotropic DNA virus that primarily infects transitional epithelium that is found in the upper aerodigestive tract and anogenital regions. Over 120 different HPV types have been identified, but the subtypes implicated in OPSCC include HPV-16, 18, 31, 33, and 35, with HPV-16 identified in approximately 90% of HPV-positive tumors. The malignant potential of the HPV infection lies in the expression of viral oncoproteins E6 and E7; which, in turn, are able to inactivate 2 human tumor-suppressor proteins, p53 and pRb.

HPV is predominately a sexually transmitted disease, and infection is an independent risk factor for development of OPSCC. Its association with the development of cervical cancer and other anogenital malignancies is well known. People with HPV-16 oral infection are at a 15-fold higher risk for OPSCC and a 50-fold increased risk for HPV-positive HNSCC. As reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2007, lifetime number of vaginal sex partners of 26 or more was associated with development of OPSCC; so too was a lifetime number of oral-sex partners of 6 or more (with a 9-fold increase in relative risk). Synergy between tobacco and alcohol abuse/use and HPV infection with increased odds of OPSCC was not found.

HPV-positive OPSCC patients have been found to have significantly better outcomes as compared to HPV-negative patients, with a 28% lower risk of death than the HPV-negative patients. Also, nonsmoking patients with HPV- positive tumors have better disease-specific survival rates as compared with smokers with HPV-positive tumors. Black patients with head and neck cancer live significantly shorter periods after treatment than white patients, at least in part due to the fact that the black population in the United States has dramatically lower rates of HPV infection than Caucasian population. HPV status directly correlates with the significant survival disparities between the 2 patient groups. When survival is compared between black and white HPV-negative patients, survival is similar.

HPV-positive tonsillar cancers have been shown to have a lower number of chromosomal alterations as compared to HPV-negative OPSCC. HPV-associated OPSCCs are more likely to be undifferentiated and have basaloid histology and more frequent nodal metastasis. HPV-negative tumors, in contrast, have keratinized rather than nonkeratinized histology. Improved overall and disease-free survival after surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy have been reported in HPV-positive OPSCC.

American Joint Committee on Cancer staging

Appropriate staging of cancer at the time of presentation is important, as stage predicts survival rate and guides management. Prognosis and treatment are directly linked to cancer stage (based largely on anatomic factors) as well as other nonanatomically based patient or tumor-specific factors such as overall health, age, sex, race, and the tumor type or biology of malignancy. Evidence-based treatment paradigms are defined by reported outcomes relative to stage and treatment received. Interdisciplinary and interinstitutional reporting of results needs to be reproducible, clear, consistent, and comparable. With accurate staging, careful follow-up, and multidisciplinary input, treatment outcomes can be compared and related back to stage at presentation.

With the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 7 staging of OP cancer, as with all head and neck cancers, staging is primarily based upon anatomic information ( Tables 1 and 2 ). For OP, the AJCC 7 has only one change as compared to AJCC 6. The T4 lesions have been divided into T4a and T4b categories. T4a lesions are moderately advanced local disease, and T4b lesions are very advanced local disease. In association with the new stratification of T4 lesions, stage IV has been subdivided into stage IVA (moderately advanced local/regional disease), stage IVB (very advanced local/regional disease), and stage IVC (distant metastatic disease). For head and neck cancers, in general, the terms resectable and unresectable are replaced with moderately advanced and very advanced in the current staging manual. Extracapsular spread (ECS) of nodal disease is specifically denoted as ECS + (present) or ECS – (absent).

| Primary Tumor (T) | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ |

| T1 | Tumor 3 cm or less in greatest dimension |

| T2 | Tumor more than 2 cm but not more than 4 cm in greatest dimension |

| T3 | Tumor more than 4 cm in greatest dimension or extension to the lingual surface of the epiglottis |

| T4a | Moderately advanced local disease Tumor invades the larynx, extrinsic muscle of tongue, medial pterygoid, hard palate, or mandible a |

| T4b | Very advanced local disease Tumor invades lateral pterygoid muscle, pterygoid plates, lateral nasopharynx, or skull base or encases carotid artery |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, 3 cm or less in greatest dimension |

| N2 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, more than 3 cm but not more than 6 cm in greatest dimension; or in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension; or in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| N2a | Metastasis in single ipsilateral lymph node more than 3 cm but not more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| N2b | Metastasis in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| N2c | Metastasis in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| N3 | Metastasis in a lymph node more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

a Mucosal extension to lingual surface of epiglottis from primary tumors of the base of tongue and vallecula does not constitute invasion of larynx.

| Group | T | N | M |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| II | T2 | N0 | M0 |

| III | T3 | N0 | M0 |

| T1 | N1 | M0 | |

| T2 | N1 | M0 | |

| T3 | N1 | M0 | |

| IVA | T4a | N0 | M0 |

| T4a | N1 | M0 | |

| T1 | N2 | M0 | |

| T2 | N2 | M0 | |

| T3 | N2 | M0 | |

| T4a | N2 | M0 | |

| IVB | T4b | Any N | M0 |

| Any T | N3 | M0 | |

| IVC | Any T | Any N | M1 |

The importance of a thorough physical examination and clinical assessment of the primary lesion cannot be overemphasized. Cross-sectional and metabolic imaging is complementary, and can further define the T, N, and M status of the patient. In AJCC 7, general rules for tumor node metastases (TNM) staging after include

Microscopic confirmation of malignancy is needed.

When uncertainty exists with assignation of T, N, or M status, the lower category should be assigned.

Separate staging and independent reporting of synchronous primary tumors is necessary.

The guidelines also state that the clinical (pretreatment) stage assigned prior to institution of therapy (surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, or a combination thereof) is not changed on the basis of new information obtained at the time of pathologic examination.

The T portion of the TNM staging classification defines the malignancy by size or contiguous extension. T designation in the OP is mainly size-based for tumors confined to the OP and includes T1: a tumor 2 cm or less in size, T2: a tumor 2 to 4 cm in size ( Fig. 4 ), and T3: a tumor larger than 4 cm in size or with extension to the lingual surface of the epiglottis. T4 tumors have extension into adjacent structures. Moderately advanced local disease, T4a, is defined as tumor invasion of larynx ( Fig. 5 ), extrinsic tongue muscles ( Fig. 6 ), medial pterygoid muscle, hard palate, or mandible. T4b classification is used with very advanced local disease when tumor encases the internal carotid artery (ICA), invades the lateral pterygoid muscle or pterygoid plates, or extends into the lateral nasopharynx or skull base ( Fig. 7 ).