To accurately interpret pretreatment and posttreatment imaging in patients with hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), one must understand the complex anatomy of this part of the aerodigestive system. Common patterns of spread must be recognized, andpitfalls in imaging must be understood. This article reviews the epidemiology, anatomy, staging, treatment, and pitfalls in imaging of hypopharyngeal SCC.

Key points

- •

To accurately interpret pretreatment and posttreatment imaging in patients with hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), one must understand the complex anatomy of this part of the aerodigestive system.

- •

Common patterns of spread must be recognized.

- •

Pitfalls in imaging must be understood.

- •

This article reviews the epidemiology, anatomy, staging, treatment and pitfalls in imaging of hypopharyngeal SCC.

Introduction and epidemiology

Compared with laryngeal neoplasms, primary hypopharyngeal (HP) tumors, especially those exclusively in the HP subsites, are relatively uncommon, accounting for about 4% of all head and neck tumors. Tumors of the hypopharynx are generally advanced stage when detected, and have often already extended to the larynx or cervical esophagus. Imaging is critical in staging these advanced primary tumors for guiding treatment planning, and because locoregional control may be difficult to attain, accurate staging is especially critical.

Epidemiology is difficult to report, as laryngeal and oral-cavity squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) statistics are often lumped together with HP numbers. Patients are generally older than 50 years, and men are more commonly affected than women at a rate of 3:1. Tobacco and alcohol abuse are the risk factors responsible for SCC, statistically the most common malignancy of the hypopharynx. Alcohol potentiates the mutagenic effects of tobacco. The biology of HP SCC is interesting, and an area of ongoing study. Mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor gene are more common in HP SCC than in other head and neck sites. Field carcinogenesis, the concept that carcinogens affect surrounding tissue that has yet to be transformed to tumor, also is common in HP SCC. Thus tumors may be multicentric, spread submucosally, and be very difficult to stage with imaging or endoscopy alone. At presentation tumors are often at an advanced stage, and the rich lymphatic drainage of the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus result in frequent nodal metastases. The role of human papillomavirus (HPV) in HP SCC is still being determined, but early evidence suggests HPV infection is less commonly involved in SCC of HP than are oropharyngeal subsites.

A rare but well-described syndrome of upper esophageal webs, iron-deficiency anemia, and postcricoid HP SCC is Plummer-Vinson syndrome. Patients are usually Caucasian women between 40 and 70 years of age. Better nutrition including iron supplementation has led to a marked decrease in this syndrome.

Introduction and epidemiology

Compared with laryngeal neoplasms, primary hypopharyngeal (HP) tumors, especially those exclusively in the HP subsites, are relatively uncommon, accounting for about 4% of all head and neck tumors. Tumors of the hypopharynx are generally advanced stage when detected, and have often already extended to the larynx or cervical esophagus. Imaging is critical in staging these advanced primary tumors for guiding treatment planning, and because locoregional control may be difficult to attain, accurate staging is especially critical.

Epidemiology is difficult to report, as laryngeal and oral-cavity squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) statistics are often lumped together with HP numbers. Patients are generally older than 50 years, and men are more commonly affected than women at a rate of 3:1. Tobacco and alcohol abuse are the risk factors responsible for SCC, statistically the most common malignancy of the hypopharynx. Alcohol potentiates the mutagenic effects of tobacco. The biology of HP SCC is interesting, and an area of ongoing study. Mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor gene are more common in HP SCC than in other head and neck sites. Field carcinogenesis, the concept that carcinogens affect surrounding tissue that has yet to be transformed to tumor, also is common in HP SCC. Thus tumors may be multicentric, spread submucosally, and be very difficult to stage with imaging or endoscopy alone. At presentation tumors are often at an advanced stage, and the rich lymphatic drainage of the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus result in frequent nodal metastases. The role of human papillomavirus (HPV) in HP SCC is still being determined, but early evidence suggests HPV infection is less commonly involved in SCC of HP than are oropharyngeal subsites.

A rare but well-described syndrome of upper esophageal webs, iron-deficiency anemia, and postcricoid HP SCC is Plummer-Vinson syndrome. Patients are usually Caucasian women between 40 and 70 years of age. Better nutrition including iron supplementation has led to a marked decrease in this syndrome.

Normal anatomy and boundaries

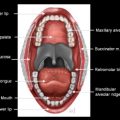

To conceptualize HP anatomy, one must understand that the larynx and the hypopharynx are so interrelated that it is impossible to know the anatomy of one without understanding the other. A simplified concept is that the larynx is immediately anterior with respect to the hypopharynx, forms the anterior wall of the hypopharynx, and the larynx “bulges into” the anterior aspect of the hypopharynx. Boundaries of the hypopharynx are often described as they relate to laryngeal subsites. The craniocaudal boundaries are quite specific: the superior boundary is at a plane at the hyoid bone level, and the inferior boundary is the lower border of the cricoid cartilage ( Fig. 1 ). As such, the hypopharynx is that portion of the aerodigestive tract between the oropharynx (superior) and the proximal cervical esophagus (inferior). The hyoid bone and cricoid are parts of the laryngeal skeleton. Immediately posterior and deep to the hypopharynx is the retropharyngeal space.

Another helpful way to understand HP anatomy is to know the individual subsite anatomy. The 3 HP subsites are the pyriform sinuses, lateral and posterior HP walls, and the postcricoid region. The pyriform sinuses are paired, right and left, and they extend from the pharyngoepiglottic folds of the suprahyoid epiglottis to the inferior cricoid cartilage. For each pyriform sinus, the lateral border is the lateral pharyngeal wall and the medial border is the aryepiglottic fold, specifically the HP surface of the aryepiglottic fold. The pyriform sinuses are shaped like upside down pyramids, with the apex located at the true vocal cord level. So even if they are collapsed and not filled with air, if the axial image is at the true vocal cord or arytenoid cartilage level, each pyriform sinus apex is posterior and lateral. The pyriform sinus is the most common location for HP SCC, accounting for about 60% of all cases.

The second subsite, the posterior HP wall, is the inferior extension of the posterior wall of the oropharynx. This portion extends to the postcricoid subsite of the hypopharynx.

The postcricoid portion of the hypopharynx, also the caudalmost region, is accurately named as located posterior to the cricoid cartilage, extending from the posterior wall of the hypopharynx at the cricoarytenoid joint level to the inferior cricoid cartilage and proximal cervical esophagus. On axial images, therefore, the mucosal overlying the posterior cricoid cartilage is the anterior aspect of the postcricoid HP. The posterior portion of the postcricoid HP is the cricopharyngeus muscle, which merges with the cervical esophagus. Postcricoid tumors are the least common of HP SCC.

American Joint Committee on Cancer staging

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging manual should be used as a guide, as it clearly lays out the anatomic details necessary to accurately stage tumors of the hypopharynx ( Table 1 ). Like other subsites, the difference between AJCC sixth and seventh editions is primarily the division of T4 lesions into T4a or moderately advanced disease and T4b, or very advanced local disease.

| Primary Tumor (T) | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ |

| T1 | Tumor limited to one subsite of hypopharynx and/or 2 cm or less in greatest dimension |

| T2 | Tumor invades more than one subsite of hypopharynx or an adjacent site, or measures more than 2 cm but not more than 4 cm in greatest dimension without fixation of hemilarynx |

| T3 | Tumor more than 4 cm in greatest dimension or with fixation of hemilarynx or extension to esophagus |

| T4a | Moderately advanced local disease Tumor invades thyroid/cricoid cartilage, hyoid bone, thyroid gland or central compartment soft tissue (includes prelaryngeal strap muscles and subcutaneous fat) |

| T4b | Very advanced local disease Tumor invades prevertebral fascia, encases carotid artery, or involves mediastinal structures |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, 3 cm or less in greatest dimension |

| N2 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, more than 3 cm but not more than 6 cm in greatest dimension; or in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension; or in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| N2a | Metastasis in single ipsilateral lymph node more than 3 cm but not more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| N2b | Metastasis in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| N2c | Metastasis in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| N3 | Metastasis in a lymph node more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| Note: Metastases at level VII are considered regional lymph node metastases | |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

Staging HP tumors requires both clinical and radiologic information. Knowledge of the specific subsites and the maximum diameter of the tumor are essential (see Table 1 ). A T1 tumor involves one subsite (posterior pharyngeal wall, pyriform sinus, or postcricoid hypopharynx) or is 2 cm or smaller in greatest dimension ( Figs. 2–4 ). A T2 tumor invades another HP subsite or an adjacent site (for example, a laryngeal subsite), or is greater than 2 cm but less than 4 cm ( Fig. 5 ). By definition, there is no fixation of the hemilarynx for a T1 or T2 tumor.

Fixation of the hemilarynx is defined as impaired motion of the true vocal cord. For HP SCC, this can be a result of tumor invading the larynx at the cricoarytenoid joint or the intrinsic laryngeal muscles. Thus, the vocal cord paralysis is from tumor extending from the hypopharynx into the larynx. Other mechanisms for vocal cord dysfunction from HP SCC are invasion of the recurrent laryngeal nerve or direct invasion of the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle. Tumor on the medial pyriform sinus wall often involves the hemilarynx, usually at the insertion of the aryepiglottic fold to the arytenoid cartilage ( Fig. 6 ). Therefore, vocal cord motion is often impaired when the tumor is in the medial pyriform sinus. Bulky pyriform sinus carcinomas may cause hemilarynx fixation owing to a weight effect. The tumor may cause arytenoid cartilage immobility at the top of the cartilage, but the base is still mobile. The arytenoid appears immobile to the endoscopist, but there is really no histologic tumor invasion of the arytenoid cartilage. Vocal cord, and not just arytenoid cartilage mobility, should be reported by the endoscopist.