Epidemiology

Colon cancer is a major public health problem in the United States, one of the most common significant cancers in the U.S. population, and the third most common cause of cancer mortality. It ranks third to lung and prostate cancer in men and third to lung and breast cancer in women. The American Cancer Society estimates that in the year 2014 about 136,830 will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer and that about 50,340 will die of the disease. The distribution of this disease varies widely throughout the world. It is common in North America, Europe, and New Zealand, but the incidence is low in South America, Africa, and Asia. The United States has one of the highest incidences of colorectal cancer in the world. However, even within the United States, the rates of occurrence vary considerably, being higher in the North, among the urban white population, and among blacks. Viewed in a personal way, U.S. adults have approximately a 1 in 20 chance of developing colorectal cancer during their lifetime and a 1 in 40 chance of dying of this disease.

Colorectal neoplasms account for about 9% of new cancer diagnoses in the United States. The incidence rates (per 100,000) have declined from a high of 71 in 1975 to 55.7 in 2004 to 2008 for men and from 54 in 1975 to 41.4 in 2004 to 2008 for women. This decline was seen mostly in whites, whereas incidence rates for blacks have slightly increased. In the United States, the incidence rates among blacks are about 23% higher than in whites, whereas mortality rates in blacks are about 48% higher than in whites. The decline in whites is probably because of increased screening for colon cancer and subsequent polyp removal. The lack of improvement over time in blacks may reflect historic underdiagnosis of colon cancer in blacks, racial differences in the trends in prevalence of risk factors for colon cancer, and lower access and use of recommended screening tests by blacks. Blacks are more likely to be diagnosed when the disease has spread beyond the colon but, once diagnosed, are less likely than whites to receive recommended surgical treatment and adjuvant therapy.

The distribution of cancer in the large bowel is of considerable importance because it affects the diagnostic approach. Approximately 50% of these cancers occur in the rectum and sigmoid colon, within reach of the short flexible sigmoidoscope ( Fig. 59-1 ). The remainder are scattered throughout the proximal colon. Some authors suggest that there has been a shift to the right, rendering fewer cancers diagnosable by digital and short sigmoidoscopic examinations. Although the overall incidence of colorectal tumors increases with age, this increase is greatest for proximal neoplasms beyond the reach of the sigmoidoscope. Also, race and gender can independently predict the location of the cancer. Generally, more distal cancers are found in Asians than in blacks or whites. Whites have more distal cancers than blacks, and men have more distal cancers than women.

Factors Involved

Dietary Factors

The wide variation and distribution of colorectal cancer throughout the world is probably related to dietary differences. In general, diets low in fiber and high in fat and animal protein (especially high and prolonged consumption of red or processed meat) are associated with a higher prevalence of colorectal cancer, which is inversely related to the incidence of gastric cancer. However, these conclusions are based on population studies, and a direct link between diet and colon cancer has not been demonstrated.

Hereditary Factors

The role of heredity in colorectal cancer has been a subject of considerable interest. Heredity probably plays a role in 5% to 6% of all cases of colorectal cancer. Adenomatous polyposis coli (see Chapter 61 ) is transmitted by the classic mendelian dominant inheritance pattern, and almost all patients with this condition eventually develop colorectal carcinoma. They account for approximately 1% of colorectal cancers. Another 5% occur in patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC). HNPCCs are subdivided into those in which colorectal cancer is clustered in families (type I) and those in which there is a familial clustering of colorectal cancer with other malignancies, such as carcinomas of the endometrium, ovary, and breast (type II). In all these syndromes, carcinomas tend to occur in the proximal part of the colon and are found at a relatively young age.

It has been suggested that an abnormality in the genetic material may be associated with the development of colorectal cancer. The discovery of four human mismatch repair genes ( hMSH2, hMLH1, hPMS1, and hPMS2 ) has provided novel insight into the genetic basis of this disease and raised the possibility of genetic diagnosis for the management of HNPCC patients and their family members. Therefore, it may be important to perform DNA testing in families suspected of having HNPCC.

Risk Factors

Although colorectal cancer is common in the U.S. population, several factors place individuals at higher than normal risk. These include older age, a personal or family history of colorectal polyps or cancer, certain hereditary conditions, diets high in saturated fat but low in fiber, excessive alcohol consumption, sedentary lifestyle, obesity, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The onset of colorectal cancer is clearly related to age. The incidence increases markedly in those older than 50 and peaks in those about 70 years old. First-degree relatives of patients with colon cancer have a twofold to threefold increase in cancer risk, as do patients who have previously been treated for colon cancer.

Patients with chronic ulcerative colitis have a higher incidence of colorectal cancer. The incidence starts to increase after the disease has been present for about 10 years, and approximately 10% develop cancer for every decade after 10 years of disease activity. These cancers tend to be more uniformly distributed throughout the colon, with a trend toward a more proximal location, and they often have a scirrhous appearance. Patients with pancolitis are predominantly affected. Sclerosing cholangitis is associated with a strong risk of developing colon cancer in patients with IBD; consumption of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) exerts a protective influence. The incidence, characteristics, and prognosis of colorectal carcinoma complicating Crohn’s disease are similar to the features of cancer in ulcerative colitis, including young age, multiple neoplasms, long duration of disease, and more than a 50% 5-year survival rate.

Pathogenesis

In the past, there was considerable controversy regarding the adenoma-carcinoma sequence. However, it is now believed that at least 70% of colorectal carcinomas start as benign adenomas that undergo malignant transformation (see Fig. 59-1 ). Up to 30% of cancers arise from a de novo sequence—that is, carcinoma developing in normal mucosa without an antecedent adenoma. Larger adenomas (>1 cm) pose a greater cancer risk. Thus, it is vital to detect and remove polypoid lesions larger than 1 cm. Their removal prevents the subsequent development of cancer. If the polyp has become a colon cancer, the earlier it is removed, the less likely it is to have spread.

Cancers that develop in patients with IBD generally arise from areas of high-grade mucosal dysplasia rather than from adenomatous polyps. Therefore, in the surveillance of these patients, blind biopsy specimens are often taken throughout the colon in an attempt to detect severe and persistent dysplasia.

Clinical Aspects

Colorectal cancer is a slow-growing malignancy, requiring a period of 7 to 10 years for a benign adenoma to undergo malignant transformation. Ideally, the disease should be detected before it becomes symptomatic. Colorectal cancer is sufficiently common in the Western world that routine screening is recommended. The American Cancer Society recommends that starting at age 50, men and women at average risk for developing colorectal cancer should follow one of the screening options listed below ;

- •

Fecal occult blood test (FOBT) or fecal immunochemical test (FIT) every year

- •

Stool DNA test, interval uncertain

- •

Flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years

- •

FOBT or FIT every year, plus flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years

- •

Double-contrast barium enema every 5 years or

- •

Colonoscopy every 10 years

- •

Computed tomography colonography (CTC) every 5 years

- •

The American College of Radiology recommends periodic (≈ every 5 years) double-contrast barium enema study, especially for patients at higher than normal risk of developing colorectal cancer. A cost-effectiveness study of double-contrast barium enema in the screening for colorectal carcinoma has shown that the double-contrast barium enema is a cost-effective screening procedure in average-risk patients. The results were based on the assumption that a missed benign 10-mm adenomatous polyp could become malignant within 5 years. Recent advances with CT colonography should aid in clarifying its exact role and further expands its role in screening and diagnosing patients with colorectal polyps or cancer (see Chapters 53 and 54 ).

If patients are at an increased risk for colon cancer, they should be tested at an earlier age than 50 years. In this group are patients with IBD, a personal or family history of colorectal polyps or colorectal cancer, and genetic syndromes, such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer.

Symptomatic colorectal cancer most often presents as bleeding. The severity of bleeding may range from the presence of occult blood in the stool to the passage of bright red blood per rectum to the development of iron deficiency anemia. The patient’s symptoms are usually related to the location of the tumor. Approximately one third of carcinomas are in the rectum and can be reached by the examining finger or a rigid proctoscope. About 50% of large bowel cancers are in the left half of the colon and can be reached with the flexible sigmoidoscope. Left-sided tumors often present with bright red rectal bleeding or constipation caused by obstruction. The remaining tumors are scattered throughout the colon. Cecal carcinomas constitute about 10% of the entire group and are most likely to present as iron deficiency anemia caused by chronic blood loss. Other frequent symptoms of colorectal cancer include abdominal pain, which may be related to the development of obstruction or to tumor invasion of adjacent tissues. Patients may also present with a change in bowel habit or nonspecific symptoms, such as weight loss or fever.

Radiology and Diagnostic Methods

Radiology plays a critical role in the diagnosis and management of patients with colorectal cancer. The double-contrast barium enema may be used for screening, especially for patients who are at higher than normal risk. It also can be used as a primary method for diagnosing symptomatic colorectal cancer. Single-column studies should be considered for detecting complications, such as obstruction or perforation. Radiology using multidetector computed tomography (MDCT), CTC, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and/or transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) also plays an important role in tumor detection and staging. Treatment decisions are often based on results from positron emission tomography and CT (PET/CT). Radiology has a significant role after treatment for colorectal cancer in the detection of recurrent disease, local and distant metastases, and metachronous colon tumors.

Contrast Enema

Radiologic examination of the colon can be performed with a single- or double-contrast technique. In most cases, double-contrast enema is superior for the examination of the rectum and the detection of small lesions. In most series of double-contrast studies, polyps are demonstrated in 10% to 13% of all patients, whereas in single-contrast studies, polyps are found in 7% of patients.

Colonoscopy

Many studies have claimed to show that colonoscopy is superior to contrast enema for the detection of polypoid lesions. However, most of these studies do not compare state of the art barium techniques with operators of similar interest and experience. There is an error rate inherent in colonoscopy. Part of this error rate derives from failure to reach the cecum in 15% of cases. In addition, there are blind spots within the colon. Generally, these are behind folds or around flexures, and polyps or even large cancers in these regions can be missed ( Fig. 59-2 ). If there are significant radiologic-endoscopic discrepancies, they should be resolved by consensus or by further examination, and it should not be assumed that the endoscopy result was correct.

Colonoscopy and double-contrast enema examinations have comparable overall accuracy, with detection of approximately 90% of all polypoid lesions if the radiographic examination is performed by an experienced radiologist with special interest in gastrointestinal (GI) radiology. However, the cost and complications of colonoscopy are considerably higher than those for double-contrast barium enema. Colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy should always be used to evaluate suggestive findings in contrast enema studies, particularly in patients with marked diverticular disease. It should also be used for biopsy of lesions and removal of polypoid lesions.

Cross-Sectional Imaging

CT has been used to detect and stage many tumors, including primary and recurrent colorectal neoplasms, and has been joined by MRI, TRUS, scintigraphy with monoclonal antibody (MoAb) imaging, and PET. 3D virtual reality techniques, such as CTC, have been used with increasing frequency, and results are excellent.

Few studies present an in-depth assessment of the value of the various techniques. A review of the large body of literature on this topic reveals many conflicting reports about the effectiveness of the various methods and opposing recommendations for their use. In many cases, this disagreement is because of early, overly enthusiastic conclusions about high success rates with each new imaging technique and underestimation of their pitfalls. Also, some literature reports contain incomplete proof of pathology or neglect to include all factors necessary for complete staging of colon neoplasms.

Benign Epithelial Polyps

Incidence

Benign tumors of the colon are extremely common and usually do not cause symptoms. These polyps are found in 10% to 12.5% of patients studied with double-contrast techniques, and the incidence rises dramatically with increasing age ( Fig. 59-3A ). Polyps occur most frequently in the left colon and are scattered throughout the remainder of the transverse and right colon ( see Fig. 59-3B ). As people age, there is a shift in the incidence of polyps to the right side of the colon, coinciding with a shift in the distribution of colon carcinoma to the right.

Pathology

The term polyp refers only to a focal, protruded lesion within the bowel. In general terms, a polyp may be neoplastic or non-neoplastic. Most non-neoplastic polyps are inflammatory or hyperplastic. They are generally small and usually occur in the distal colon. Neoplastic polyps may represent true neoplasms of any component of the bowel wall. Epithelial neoplasms—adenomas—are the most important because they serve as precursors to colorectal carcinoma. The demonstration of a polypoid lesion on a barium enema does not necessarily provide information regarding its pathologic nature. Whenever possible, polyps larger than 1 cm in diameter must be removed, preferably by colonoscopic polypectomy ( Fig. 59-4 ), because of the increased risk of harboring a malignancy.

Most colonic adenomas are tubular adenomas. However, tubular adenomas have various degrees of villous change and, as a polyp becomes larger, the degree of villous change increases. At the other end of the spectrum, some polyps are villous adenomas because the surface consists of frondlike structures arising from the base of the mucosa. Thus, there may be a transition from tubular adenoma to tubulovillous adenoma to villous adenoma. It has been suggested that any adenoma with more than 75% villous change should be referred to as a villous adenoma. In general, the risk of carcinoma is related to the proportion of villous change in an adenoma.

In small adenomas, it may be impossible to distinguish villous change radiologically. However, as the adenoma becomes larger and the proportion of villous change increases, a reticular or granular mucosal surface may be seen ( Fig. 59-5A ). Large villous adenomas have an atypical radiologic appearance. They are large, bulky polypoid masses with barium caught between the frondlike protrusions, producing a lacy surface pattern (see Fig. 59-5B ). Large villous tumors should be removed completely because malignant degeneration may occur in only a portion of the tumor, and random biopsy sampling is unreliable for the detection of malignant change.

Other non-neoplastic polyps may also be found in the colon. These include juvenile polyps, which may be single or multiple and may be found in adults and in children. Hamartomatous polyps are found in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and inflammatory polyps in patients with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (see Chapter 61 ).

Polyp Detection

Barium Enema

A polyp may be demonstrated as a radiolucent filling defect, contour defect, or ring shadow because it is simply a protrusion of the mucosa into the bowel lumen (see Chapter 2 ). The greatest and most frequent difficulty arises in distinguishing polyps from fecal residue. In general, fecal residue is mobile and is usually found on the dependent surface in the barium pool. In addition, several features may suggest that the filling defect represents a true polyp. These include the bowler hat sign ( Fig. 59-6A ) and Mexican hat sign (see Fig. 59-6B ). Although the bowler hat sign can also be produced by a diverticulum, the direction of the dome of the bowler hat distinguishes a polyp from a diverticulum. When the dome of the hat points away from the axis of the bowel, the lesion is a diverticulum; when the dome points toward the lumen of the bowel, it is a polyp. Villous adenomas may have a reticular or granular surface because of barium trapped between the fronds of the tumor. These signs are illustrated and discussed in detail in Chapters 2 and 3 . Some hyperplastic polyps may not appear as smooth sessile lesions measuring 5 mm or less, but as larger lobulated lesions that cannot be distinguished morphologically from adenomatous polpys.

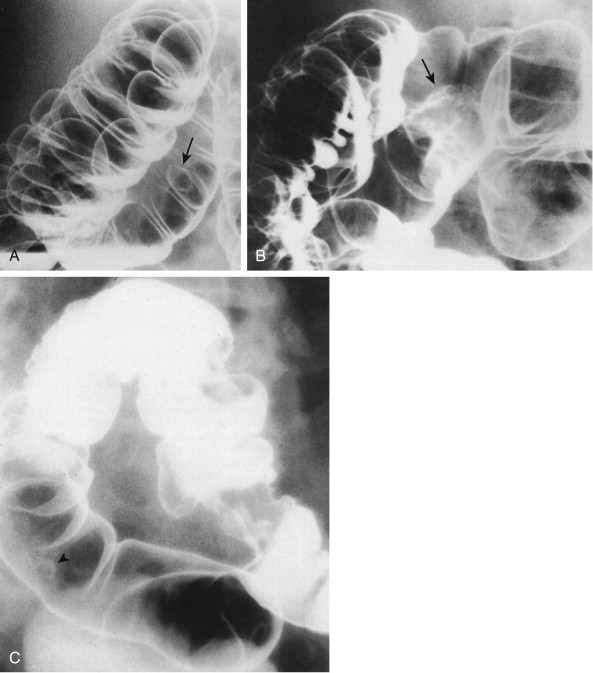

Rubesin and coworkers have used the term carpet lesion to describe a flat lobulated lesion that is manifest primarily as an alteration in the surface texture of the bowel ( Fig. 59-7A ). These lesions may be large and are mostly tubular adenomas with varying degrees of villous change. In some cases of colorectal carcinoma, the background of a benign carpet lesion can be recognized (see Fig. 59-7B ).

Cross-Sectional Imaging

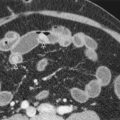

Benign lesions of the colon, such as hyperplastic polyps or adenomatous polyps, are usually not examined by CT or MRI. They are demonstrated by barium examinations or by an endoscopic technique and are seen during CT or MRI examinations only incidentally. These techniques are used only if these benign tumors become large enough to have a high likelihood of harboring a malignancy. Benign polyps appear as sessile soft tissue masses that protrude into the lumen of the bowel on axial images ( Fig. 59-8 ). They are usually detected only if the patient has undergone colonic cleansing or if the polyp is large. If the polyp is pedunculated, CT scans may demonstrate a large polypoid mass that represents the combined polyp and stalk (see Chapter 53 ).

Kim and colleagues have suggested that villous adenomas have a characteristic CT appearance based on their high mucus content. The CT features of villous adenomas include homogeneous water density (<10 HU) occupying more than 50% of the lesion and an eccentric location on the luminal side of the mass. No air-fluid level is seen, and the lesion should not have a round cystic configuration. Opaque oral or rectal contrast material should not be used to diagnose a suspected villous adenoma because it obscures the lesion. In these cases, insufflation of air, water, or oily substance administered per rectum may be helpful. Because of their malignant potential, larger villous adenomas should always be staged by CT or TRUS if located in the rectum.

On MRI scans, benign polyps appear as low-intensity structures on T1-weighted spin-echo sequences. If there are many mucin-producing cells, the signal intensity of the polypoid mass increases on T1-weighted sequences. TRUS is used for assessment of sessile polyps large enough to have an increased risk for malignancy. In these cases, TRUS can be used to determine the depth of invasion by a sessile mass that protrudes into the lumen. The depth of invasion is best assessed by TRUS because it is the only method that can demonstrate the various layers of the colonic wall. If the intraluminal component is large, false tumor measurements and erroneous depiction of the surface of the mass can occur because of compression of the tumor by the transrectal probe.

Adenocarcinoma

Barium Enema

Early Cancer

The radiologic detection of early colorectal cancer is basically an exercise in the detection of polyps. The typical early colon cancer is a flat, sessile lesion that may produce a contour defect ( Fig. 59-9 ). Although most polyps detected radiologically should be removed if they are larger than 5 mm in diameter, a number of radiologic criteria have been used for the detection of malignancy in colorectal polyps. The size of the polyp is the most important criterion. Carcinoma is very rare in polyps smaller than 5 mm. The incidence of cancer is approximately 1% in polyps in the 5- to 10-mm range ( Fig. 59-10 ), 10% in polyps measuring between 1 and 2 cm, and more than 25% in polyps larger than 2 cm.

Malignant polyps tend to grow more quickly than benign polyps, although there is considerable overlap between the two groups. If there is definite evidence of polyp growth on serial examinations, malignancy should be suspected. The presence of a long thin stalk is generally a sign of a benign polyp. Rarely, these polyps harbor malignancy. As a rule, the stalk associated with carcinoma is short and thick ( Fig. 59-11 ). If the head of the polyp is irregular or lobulated, the probability of malignancy is greater, although some benign polyps may have an irregular or lobulated surface.

Advanced Cancer

Most patients with symptomatic colorectal carcinoma have advanced lesions. These lesions are generally annular or polypoid tumors seen as filling defects in the barium column or as contour defects. In addition, plaquelike lesions can produce abnormal lines on double-contrast barium studies ( Figs. 59-12 and 59-13 ). Annular or semiannular carcinomas as seen with barium enema have a higher rate of serosal invasion and lymph node metastases than polypoid carcinomas.

Advanced cancers are often associated with sentinel polyps or additional polyps elsewhere in the colon. Approximately 5% of patients who have a colon carcinoma have additional, synchronous carcinomas in the colon (see Fig. 59-13 ). Therefore, whenever possible, the entire colon should be examined, even when a carcinoma is encountered in the distal bowel. The barium enema may be used to search for neoplastic lesions larger than 1 cm in patients with incomplete colonoscopy.

Carcinomas are particularly difficult to detect in patients with extensive diverticular disease of the sigmoid colon ( Fig. 59-14 ). If the radiologic examination leaves any doubt regarding the presence of a carcinoma, flexible sigmoidoscopy should be recommended to confirm or exclude lesions in the sigmoid colon.

Advanced carcinoma may have an atypical appearance. The linitis plastica type of carcinoma has predominant submucosal infiltration and fibrous reaction. The radiologic appearance may be suggestive of an inflammatory stricture. This type of carcinoma is particularly likely to develop in patients with ulcerative colitis (see Chapter 57 ).

Complications

The most important complications of colorectal cancer include bleeding, bowel obstruction, and perforation. Massive rectal bleeding caused by colon carcinoma is rare; the bleeding is more often manifest as occult blood in the stool or as chronic anemia. Colorectal cancer is one of the major causes of large bowel obstruction. Obstruction may be caused by encroachment of the tumor mass on the lumen of the bowel ( Fig. 59-15A ). Antegrade and retrograde obstruction tend to be poorly correlated. Frequently, there is a high-grade obstruction to the retrograde flow of barium when the patient has few or no symptoms of clinical obstruction. In the case of polypoid tumors, obstruction may also be caused by colocolic intussusception (see Fig. 59-15B ). In patients with long-standing obstruction and colon distention, mucosal ischemia may result in an ulcerative form of colitis affecting the colon proximal to the obstruction.

Advanced cancer may result in perforation of the colon and a pericolic abscess ( Fig. 59-16A ). The signs, symptoms, and radiologic features of a perforated carcinoma may be difficult to distinguish from those of a pericolic abscess associated with diverticulitis (see Fig. 59-16B ). However, evidence of GI blood loss makes a malignant origin much more likely. Perforation of the colon may lead to a fistula to adjacent organs, such as the stomach ( Fig. 59-17A ), duodenum (see Fig. 59-17B ), bladder, or vagina. The fistulous communication can be demonstrated by barium study or by the extracolonic presence of gas or contrast medium on CT scans.

Computed Tomography

Primary Colorectal Carcinoma

CT and endoluminal ultrasound are better suited for the evaluation of tumor stage than manual examination, barium enema, or fiberoptic techniques. In the presence of a colorectal cancer, CT and ultrasound may visualize a discrete mass ( Fig. 59-18 ) or focal wall thickening ( Fig. 59-19 ), but this finding is nonspecific and requires further investigation. The wall thickening may be circumferential, with or without extension beyond the bowel wall ( Figs. 59-20 and 59-21A ). Water introduced per rectum and multiplanar reconstructions often help delineate a tumor better (see Fig. 59-21B ). Asymmetric mural thickening, with or without an irregular surface contour, is suggestive of a neoplastic process (see Fig. 59-20 ), particularly if benign causes can be excluded by history or physical examination. In the anorectal region, internal hemorrhoids must be distinguished from a polypoid malignancy.

With a properly distended lumen, a colonic wall thickness less than 3 mm is normal, 3 to 6 mm is indeterminate, and more than 6 mm is definitely abnormal. If the tumor is contained within the wall of the colon or rectum, the outer margins of the large bowel appear smooth. CT cannot reliably assess the depth of mural penetration. The various layers of bowel wall and depth of mural invasion can be depicted by endoluminal ultrasound or MRI with endorectal coils. These techniques can also determine the layer from which the tumor arises, which is important for differentiating an adenocarcinoma from a lymphoma or GI stromal tumor.

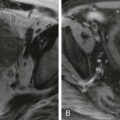

Tumor invasion beyond the bowel wall is suggested by a mass with nodular or spiculated borders, associated with strands of soft tissue extending from the muscularis propria into the perirectal fat or from the serosal surface into the pericolonic fat ( Fig. 59-22 ). Broad-based soft tissue extensions from the tumor into the perirectal fat are more indicative of tumor extension than spiculation, which often represents a desmoplastic reaction. Desmoplastic reaction frequently leads to overstaging by MRI because it can be difficult to distinguish between fibrosis alone and fibrosis that contains tumor cells ( Fig. 59-23 ). Extracolonic tumor spread is also suggested by loss of tissue fat planes between the large bowel and surrounding muscles, such as the obturator internus, piriformis ( Fig. 59-24 ), levator ani, puborectalis, coccygeal, and gluteus maximus. Invasion is definite only when a tumor mass extends directly into an adjacent muscle, obliterating the fat plane and enlarging the individual muscle. Cross-sectional methods such as CT cannot detect microscopic invasion of the fat surrounding the colon or rectum (see Fig. 59-19 ) and tend to understage these patients. Spread to contiguous organs in the pelvis can be simulated by absence of tissue planes between the viscera and tumor mass, without actual invasion. Vascular or lymphatic congestion, inflammation, or actual absence of fat because of severe cachexia can cause obliteration of fat planes. Therefore, invasion should be diagnosed cautiously and considered definite only if an obvious mass clearly involves an adjacent organ. Distinction between tumor infiltration of adjacent muscle and simple absence of fat separating normal structures is particularly difficult in the area of the lower rectum and anal verge.

In our experience, CT results can be improved through the use of a large, rapidly delivered bolus of intravenous (IV) contrast agent and MDCT with thin sections and water as rectal and colonic contrast material (see Fig. 59-23 ). With this approach, the pelvis is scanned at peak enhancement, and the enhanced wall of the rectum can be better distinguished from adjacent levator ani and sphincter muscles. CT generally is used for staging and not for detection of colonic lesions. Nevertheless, ultrathin sections (0.625- to 1.25-mm slices) obtained with MDCT can facilitate the demonstration of even small lesions and increase the accuracy of tumor staging. Staging results can be further improved if multiplanar reformats are used, and interpretation is based on a combination of axial slices and multiplanar reformats (see Fig. 59-18 ). Coronal reformats often are helpful to define the relationship of the rectal mass to the levator ani, puborectalis, and sphincter muscles, which is helpful in planning the appropriate surgery. Nevertheless, CT cannot achieve the exquisite soft tissue resolution afforded by MRI with gadolinium contrast enhancement. Such superior distinction is particularly useful in the lower pelvis for assessing tumor relationship to the mesorectal fascia and invasion into muscle, nerves, bladder, and male or female organs (see later, “ Magnetic Resonance Imaging ”).

Primary and recurrent colon cancer can invade the seminal vesicles, prostate, bladder, uterus ( Fig. 59-25 ), ovaries, small bowel, and sciatic nerves and can obstruct the ureters. Occasionally, tumors of the prostate, uterus, or ovaries that invade or are contiguous with the rectum or sigmoid colon can be indistinguishable from an invasive colon neoplasm. Areas of low attenuation within the mass suggest tumor necrosis; tumor calcifications indicate a mucinous adenocarcinoma. A vesicorectal fistula manifests as air in the tract and bladder. After administration of an IV contrast agent, the wall of the tract may enhance. Alternatively, a jet of positive rectal contrast material can be identified in the bladder. Fistulous tracts can also extend into the uterus or vagina, and sinus tracts may be seen in the fat of the ischiorectal fossa.

Colon tumors can destroy adjacent bone, usually the sacrum and coccyx. Large tumors can involve the ilium. Advanced bone invasion causes frank bone destruction often associated with a soft tissue mass. Subtle cortical destruction visible only on bone window settings may be the only manifestation of bone invasion.

Liver metastases usually appear hypodense on non–contrast-enhanced scans. Foci of calcification can be seen within primary or metastatic mucinous adenocarcinomas ( Fig. 59-26 ). After a bolus injection of contrast material, the CT density of hepatic colonic metastasis can change rapidly. Compared with the uninvolved liver parenchyma, metastases often show early rim enhancement or become partially hyperdense ( Fig. 59-27 ), go through an isodense phase, and then become low-density lesions again. Optimal bolus and scanning techniques are necessary to minimize false-negative results that can occur when metastases become isodense with normal liver parenchyma when scanning is extended into the equilibrium phase. This isointensity often occurs with small (<2 cm) lesions. If only one to four hepatic metastases are detected (more if they are peripheral and can be easily wedged out), and no extrahepatic disease is present, an aggressive treatment plan appears warranted, because there is improved 5-year survival after removal of isolated metastatic foci by resection or ablation.

CT with arterial portography (CTAP) was formerly considered the single most accurate means of detecting additional metastatic lesions in the normal-appearing lobe. However, the general use of CTAP has been abandoned in favor of helical CT. Helical CT can achieve similar sensitivities, has a lower false-positive rate than CTAP, and is noninvasive. In one helical CT study with surgical correlation in all patients, the sensitivity for detecting colonic metastases to the liver was 85% and the positive predictive value was 96%. MRI with ferumoxides or gadolinium enhancement also provides excellent results in distinguishing hepatic metastases from colon carcinoma, but this technique is more expensive and not as widely available as CT. In one series, the MRI sensitivity for colorectal liver metastases was 96.8% but only slightly over one third of patients underwent curative resection for histologic confirmation. More recently, MRI enhanced with gadoxetate disodium (Primovist in Europe and Eovist in the United States, Bayer Pharmaceuticals) has shown excellent results for assessing hepatic metastases from colonic carcinoma and were superior to MDCT. Large series are still needed to establish the true cost-effectiveness of the various techniques. Intraoperative ultrasound is often used as the gold standard, but not all published studies had histopathologic correlation. In patients for whom resection is not an option, thermal tumor ablation or selective catheterization and intra-arterial chemotherapy of the liver are often used, but only if there is no evidence of tumor spread to extrahepatic sites. Local or distant adenopathy, adrenal metastases, peritoneal carcinomatosis, metastases to other areas of the GI tract, and lung metastases are some findings that preclude resection or chemoembolization of liver lesions.

Generally, rectal carcinoma metastasizes to lymph nodes along the superior rectal vessels to the mesenteric vessels for upper rectal tumors and along the middle rectal vessels to the internal iliac vessels for lower rectal tumors. Advanced low rectal or anal tumors drain along the inferior rectal vessels into the inguinal nodes. Metastases may be found in nodes in the retroperitoneum (see Fig. 59-24 ) and porta hepatis. In other areas of the colon, lymph node metastases follow the normal pattern of lymph drainage from the involved area. Local lymph nodes may or may not be demonstrated, depending on separability from the main mass and size of the lymph nodes ( Fig. 59-28 ). In the abdomen and pelvis, lymph nodes more than 1.0 cm in diameter are considered abnormal. The pathologic nature of node enlargement cannot be determined absolutely by CT, although asymmetry, irregularity of the nodal margins and, less reliably, size criteria can be used to establish lymph node abnormality.

Benign and malignant disease can produce lymphadenopathy, and often only PET or guided biopsy can provide a definitive diagnosis. Many metastatic foci are found in normal-sized lymph nodes (<1 cm) that cannot be considered abnormal by CT if size is used as the only diagnostic criterion. Pericolic lymph nodes next to a segment of thickened colonic wall are seen much more frequently in patients with colon cancer than in those with diverticulitis. Therefore, the presence of such nodes should lead to further evaluation in patients with suspected diverticulitis. Additional signs that favor a diagnosis of colon carcinoma over diverticulitis are loss of a normal enhancement pattern in the thickened bowel wall and absence of inflamed diverticula. Because hyperplastic or inflammatory nodes are rare in the perirectal area, demonstration of nonenhanced, small (<1 cm), round or oval soft tissue densities suggests the presence of malignant adenopathy ( Fig. 59-29 ).

There are certain pitfalls in the interpretation of CT scans of patients with colon tumors. CT scans obtained soon after surgery or radiation therapy can demonstrate edema or hemorrhage of the pelvic structures that simulates recurrent neoplasm. Chronic radiation changes in the pelvis may be difficult or impossible to distinguish from colon tumor without CT-guided biopsies. It is therefore essential to determine the tumor stage by CT or MRI before the patient undergoes radiation. Follow-up CT scans after irradiation are needed only to determine whether the mass seen on the staging scan has sufficiently diminished in size to become resectable. Benign bone defects can simulate metastatic foci, and nonopacified bowel loops can be mistaken for a tumor mass. Perforation of a colon cancer can result in an inflammatory mass or abscess, which makes diagnosis of the underlying cancer difficult (see Fig. 59-29 ). Cachexia can lead to loss of fat planes, which mimics direct invasion of tumor into surrounding structures.

Preoperative Staging by Computed Tomography

The staging of colon tumors has usually been based on Dukes’ classification or a modification ( Table 59-1 ). CT staging is based on an analysis of the thickness of the colon wall, extension beyond bowel wall margins, and presence or absence of tumor spread to lymph nodes and adjacent and distant organs. The size of a primary or recurrent colon tumor can be measured and the tumor assigned to one of four stages, depending on the CT findings ( Table 59-2 ).

| Astler-Coller Classification (Modified from Dukes’) | TNM Staging | Description | Approximate 5-Year Survival (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A or I | T1N0M0 | Nodes (−), limited to mucosa ± submucosa | 80 |

| B1 or I | T2N0M0 | Nodes (−), limited to muscularis ± serosa | 70 |

| B2 or II | T3N0M0 | Nodes (−), transmural into subserosa or into nonperitonealized perirectal or pericolonic tissue | 60-65 |

| C1 or III | T2N1M0 | Nodes (+), limited to muscularis ± serosa | 35-45 |

| C2 or III | T3N1M0 | Nodes (+), transmural into subserosa or into nonperitonealized perirectal or pericolonic tissue | 25 |

| T4aN1M0 | Nodes (+), perforation of tumor mass | ||

| T4bN1M0 | Nodes (+), extension into adjacent organs or structures (e.g., muscle, nerve, bone) | ||

| D or IV | Any T and N, M1 | Any of the above, plus distant metastases | <25 |

| CT Stage | TNM Staging | Description |

|---|---|---|

| I | T1 | Intraluminal mass without thickening of wall |

| II * | T2 | Thickened large bowel wall (>0.6 cm) or pelvic mass, no extension beyond bowel wall |

| IIIa * | T3 | Thickened large bowel wall or pelvic mass with invasion of adjacent pericolonic or perirectal tissue but not to mesorectal fascia |

| IIIb * | T3 | Thickened large bowel wall or pelvic mass with invasion of adjacent pericolonic or perirectal tissue with extension to mesorectal fascia |

| IIIc * | T4a and b | Thickened large bowel wall or pelvic mass with perforation or invasion of adjacent organs or structures, with or without extension to pelvic or abdominal walls but without distant metastases |

| IV * | Any T, M1 | Distant metastases with or without local abnormality |

Many surgeons use the tumor, node, metastases (TNM) classification (see Table 59-1 ) for staging colon neoplasms. It has the advantage of more precise definition of the depth of infiltration in the bowel wall. Because of the inability of CT to determine depth of invasion to or through the various layers of the colon, CT findings cannot be correlated easily with the TNM classification. For example, tumor limited to mucosa or submucosa (T1N0M0) cannot be distinguished from tumor invading the muscularis or infiltrating to but not through the serosa, if present (T2N0M0). Generally, lesions extending beyond bowel wall (T3 and T4) are correctly identified by CT unless microinvasion by tumor is present. Assessment of regional lymph node (N) involvement and distant metastases (M) must be added to the evaluation of the depth of tumor invasion.

Early reports suggested that CT findings related to local extent and regional spread of tumor correlated well with surgical and histopathologic findings, and accuracy rates of 77% to 100% were reported. The high accuracy rates of these reports were largely because of the more advanced cases in these series. For primary colon cancer, CT is more accurate in showing extensive invasion of surrounding tissue and distant metastases than in demonstrating local adenopathy or minimal tumor extension.

CT frequently understages patients with microinvasion of pericolonic or perirectal fat or small tumor foci in normal-sized nodes. Lymph node metastases were not analyzed separately in some of the earlier studies. In a meta-analysis that analyzed local staging and lymph node involvement in patients with rectal cancers, summary estimates of sensitivity and specificity for CT in assessing perirectal tissue invasion and invasion of adjacent organs were 79% and 78% and 72% and 96%, respectively. In the same study, the summary estimates of sensitivity and specificity for CT in detecting lymph node involvement were much lower and reached only 55% and 74%, respectively. One study found that staging accuracy increased from 17% for Dukes’ B lesions to 81% for Dukes’ D lesions. In another meta-analysis, the mean weighted sensitivity of helical CT for detecting hepatic metastases, mostly from colon carcinoma, was 72% at a specificity of higher than 85%. Some individual studies have reached higher sensitivities for hepatic metastases from colorectal carcinoma.

The accuracy of CT assessment of local tumor extent can be improved by prior colonic cleansing, prone positioning of the patient, air distention of the rectum, or administration of water enemas to serve as a low-density intraluminal contrast agent. Also, lowering the size threshold for diagnosing lymph node metastases improves the sensitivity for detecting such deposits, but this approach decreases specificity.

Little information is available about the CT detection and staging of tumors in the cecum or ascending, transverse, and descending colon. Most tumors in these areas are easily demonstrated ( Figs. 59-30 and 59-31 ), but no investigation has analyzed these lesions in detail.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree