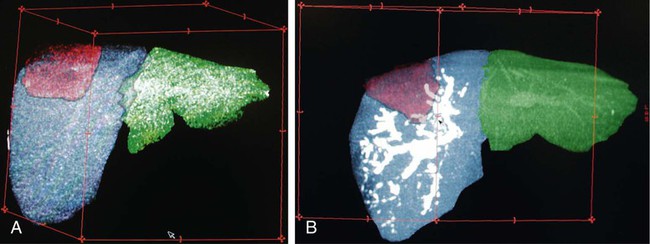

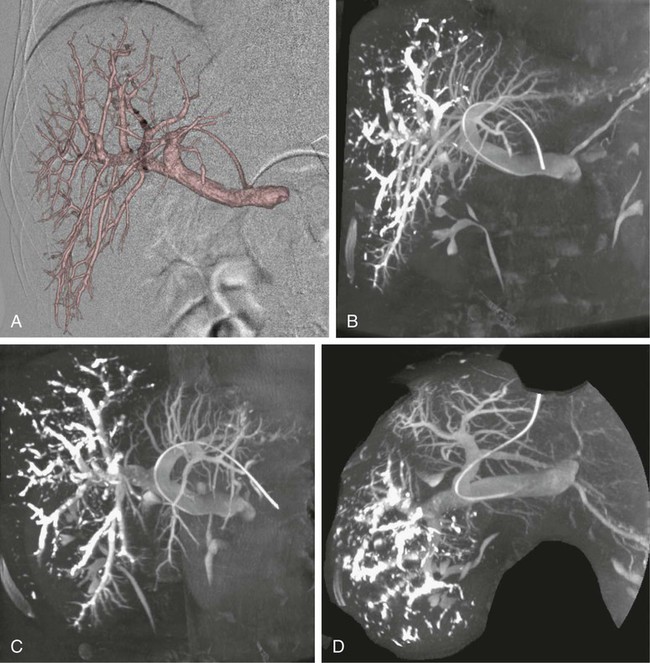

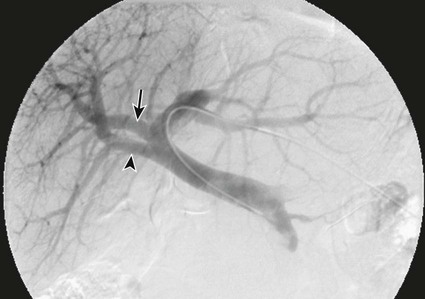

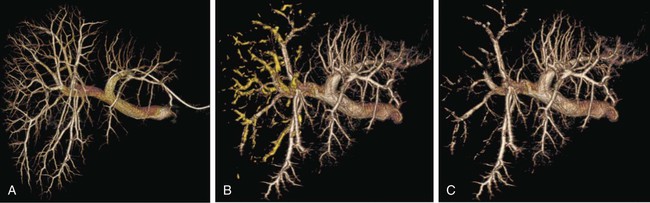

One of the prerequisites for partial hepatic resection is the presence of enough remaining functional liver parenchyma to avoid life-threatening postoperative liver failure. Therefore, the possibilities of curative resection of liver tumors are strongly dependent on the volume of the future remnant liver (FRL). In clinical practice, these possibilities are frequently limited when an extended hepatectomy is mandatory because the FRL is too small. The more frequent case is need for a right extended hepatectomy with a small left lobe. Major liver surgery is indicated in some patients with impaired liver function, whatever the cause (e.g., cirrhosis, cholestasis, fibrosis, steatosis), and this further limits the possibility of surgery because larger FRL volume is needed. It has long been demonstrated that liver trophicity closely depends on hepatic portal blood flow, and consequently portal branch ligation results in shrinkage of the corresponding lobe and hypertrophy of the contralateral one.1 In the same manner, liver atrophy occurs after surgical or spontaneous portocaval shunting, hypertrophy of the remnant liver occurs after partial hepatectomy, and the Spiegel lobe hypertrophies in Budd-Chiari disease when the caudate lobe remains the only one to still have hepatopetal portal blood flow. It was established in the 1970s that portal venous blood flow promoted hepatic cell regeneration, and that blood arising from the duodenopancreatic area had strong hepatotropic properties. Insulin and glucagon were then soon recognized as growth regulatory factors that, when infused concomitantly, synergistically stimulated hepatic regeneration.2 More recently, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) could be isolated in different laboratories and described to rise after partial hepatectomy.3 Multiple other peptides such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-α or serotonin have also been demonstrated to play a role in hepatic regeneration. Limits for hepatic resections, and consequently indications for PVE, depend on multiple factors, but FRL/total functional liver ratio for a given patient (according to age and liver function) is the main factor that determines possibilities for a safe resection. Depending on the authors, PVE is considered when this ratio is expected to be less than 25% to 40% in patients with normal liver function, and less than 40% to 50% in patients with liver dysfunction.1–3 Many studies have demonstrated that computed tomography (CT) estimations of liver volumes were correctly correlated to real volumes, despite partial volume effect, respiratory phase, or interobserver variations. Consequently, liver CT volumetry is a key examination to determine surgical possibilities and need for PVE. Because tumors do not contain functional hepatocytes, tumor volume must be subtracted from that of liver during CT volumetry. In the same manner, when radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is planned simultaneously with the hepatectomy for treating a tumor located in the FRL, one should pay attention to subtracting the volume of the future RFA lesion (tumor volume + safety margin) from the FRL volume. CT volumetry should be performed 1 month after PVE to evaluate hypertrophy of the FRL (Fig. 69-1). The procedure requires a digital subtraction angiography (DSA) suite with possible angulation of the C-arm that will aid intraportal navigation when venous anatomy is unusual and in atypical PVE before complex resections. In such complex embolization or atypical resection, three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction from cone beam CT acquisition and 3D roadmap renders catheterization easier (Fig. 69-2). On demand catheter tip can be shaped, alternatively Cobra shape can be used when approach is contralateral, or short sidewinder catheter can be used when approach is ipsilateral. Usually, a 0.035-inch hydrophilic guidewire suffices for the entire procedure. Microcatheters are used by some operators for particle embolization through ipsilateral access. A thorough knowledge of hepatic segmentation and portal venous anatomy is essential before performing PVE. The most frequent variation is slipping from right to left of segment V and VIII branches, separately or together. Therefore, two main variations are frequently encountered: (1) trifurcation of the portal vein into the left branch, segments V + VIII branch and segments VI + VII branch, when the slipping is limited and (2) bifurcation of the portal vein into a right vein limited to segments VI + VII, and left vein also giving rise to segments V + VIII branch, when the slipping is complete (Fig. 69-3). Besides knowledge of the anatomy, a clear knowledge of the plane of the hepatectomy is necessary before starting the procedure because the extent of PVE must mimic the extent of surgery, and because more and more atypical surgery is performed, many different types of PVE are possible4 (Fig. 69-4). Access can be obtained from a contralateral approach (i.e., puncture of the left portal branch and embolization of right portal branches) or an ipsilateral approach (i.e., puncture of the right to embolize right portal branches). The advantage of the contralateral approach is easier catheterization of the right lobe branches, but there is a risk of damage to the FRL. An ipsilateral approach allows for easier catheterization of segment IV branches when needed. The drawbacks of the ipsilateral approach are the difficulty of access to right portal branches in a retrograde fashion and difficulty in obtaining a good final portography, since the catheter has to pass through embolic material to be placed in the portal vein for the final contrast medium injection. Choosing the access also depends on the embolic material used. Glue can hardly be manipulated from the ipsilateral side, but large embolic materials like plugs require large-diameter access, which is less risky when obtained on the ipsilateral side. Ultimately, the choice between the ipsilateral and contralateral route should be based on their respective complication rates, which are similar and mainly related to puncture of unexpected structures like biliary branches or hepatic arteries. The largest series of contralateral PVE reviewed 188 cases performed in different centers using contralateral access as well as N-butyl cyanoacrylate as an embolic material.5 In the literature, the only factor increasing complications is puncture of the right posterior segment versus puncture of the right anterior segment,6 thus advocating puncture of the anterior segment when compatible with the location of the PVE to be performed.

Portal Vein Embolization

Indications

Equipment

Technique

Anatomy and Approaches

Technical Aspects

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Portal Vein Embolization