General Principles

Radiologic evaluation of the postoperative esophagus requires an understanding of the operative procedures and of the normal postoperative radiologic appearances. The purpose of the radiologic examination is to do the following: (1) define the postoperative anatomy and establish a baseline; (2) assess the efficacy of the procedure; and (3) detect complications during the early (<4 weeks after surgery) or late (>4 weeks after surgery) postoperative periods. During the early postoperative period, the most common complications include stasis resulting from adynamic ileus or vagotomy, obstruction resulting from anastomotic edema, and perforation resulting from anastomotic breakdown ( Box 27-1 ). During the late postoperative period, the most common complications include aspiration, gastroesophageal reflux, anastomotic strictures, and recurrent tumor (see Box 27-1 ).

Early Complications

Common Complications

Anastomotic or staple line leak

Anastomotic narrowing

Gastric or duodenal atony

Aspiration

Gastroesophageal reflux

Delayed bypass emptying

Anastomotic edema

Anastomotic narrowing

Gastric or duodenal atony

Obstruction at diaphragm—pyloric channel obstruction or spasm

Uncommon Complications

Pneumothorax

Pneumomediastinum

Mediastinal hematoma

Empyema

Vocal cord paresis

Chylothorax

Ischemia of colonic or jejunal bypass

Splenic injury

Pancreatitis

Late Complications

Common Complications

Anastomotic stricture

Aspiration

Recurrent carcinoma

Gastroesophageal reflux and its sequelae

Uncommon Complications

Delayed conduit emptying

Tracheoesophageal fistula

Anastomotic or staple line leak

An anastomotic or staple line leak is the most common serious complication of esophageal surgery ( Fig. 27-1 ). Sutures and staples hold less well in the esophagus than elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract because the esophagus lacks a serosa, esophageal muscle is stringy and soft, and mucosa retracts from the cut esophageal margin because of mobility between the squamous mucosa, fatty submucosa, and muscularis propria. Leaks also occur at staple lines because of focal ischemia caused by the crush effect of the staple line on viable tissue. A delay in the diagnosis of postoperative perforation leads to increased morbidity and mortality resulting from mediastinitis, abscess formation, or sepsis. Postoperative patients complaining of cervical, thoracic, or epigastric pain, fever, dysphagia, or respiratory distress may therefore require an emergent esophagogram. At our institution, esophagograms are routinely performed between the sixth and eighth postoperative days because some patients with esophageal perforation are asymptomatic and others have delayed leaks. Mildly delayed leaks (postoperative days 7-21) are often caused by ischemia at a staple line.

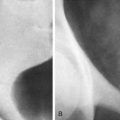

Edema, hemorrhage, and spasm at an anastomosis are the most common causes of obstruction in the early postoperative period. This obstruction usually resolves within 1 to 2 weeks after surgery. Obstruction may also occur when the viscus used as the esophageal substitute passes through the diaphragm ( Fig. 27-2 ). In the late postoperative period, obstruction is usually caused by a benign stricture related to a healed anastomotic leak, ischemia at the anastomosis, or chronic gastroesophageal reflux. Other patients may have recurrent cancer or a tight diaphragmatic hiatus as the cause of a narrowing.

Esophageal dysmotility, delayed gastric emptying caused by pylorospasm or gastric atony, or diarrhea may be the result of manipulation, damage, or intentional surgical resection of the vagus nerve. Vocal cord paralysis or dysphagia with abnormal motility of the inferior constrictor muscles or proximal esophageal muscles may result from recurrent laryngeal injury.

Any form of esophageal surgery that disrupts the lower esophageal sphincter may result in gastroesophageal reflux. An antireflux procedure may be included as part of the esophagogastric anastomosis to prevent postoperative gastroesophageal reflux. Complications of postoperataive gastroesophageal reflux include aspiration, reflux esophagitis, stricture formation, Barrett’s esophagus, and adenocarcinoma arising in Barrett’s esophagus.

The thoracic duct may also be damaged during surgery. The thoracic duct passes superiorly, anterior to the spine, between the aorta and azygos vein. At the level of the T5 vertebral body, the thoracic duct crosses behind the esophagus and then continues cranially along the left side of the esophagus. Although uncommon, thoracic duct damage may result in chylothorax or chylous ascites.

Early postoperative complications may be manifested by a variety of findings on chest and abdominal radiographs. A dilated viscus with air-fluid levels should suggest gastric outlet obstruction when the stomach is used to replace the esophagus. Pneumomediastinum, cervical or subcutaneous emphysema, a widened mediastinum, or a rapidly enlarging pleural effusion should suggest anastomotic breakdown and perforation. Nevertheless, chest and abdominal radiographs may be normal in patients with perforation.

Depending on the nature of the surgery and status of the patient, the postoperative radiologic examination should be tailored to demonstrate suspected complications. Barium and water-soluble contrast agents each have advantages and disadvantages in evaluating patients during the early postoperative period. This subject is discussed in detail in Chapters 1 and 17 . Briefly, water-soluble contrast agents should be used during the early postoperative period to rule out a perforation or anastomotic leak into the mediastinum or pleural space. If no water-soluble contrast medium is seen to extravasate from the esophagus on initial spot images, high-density barium should then be given for a more detailed examination. Barium or low-osmolality, water-soluble contrast agents such as iohexol (Omnipaque) may be used as the primary contrast agent if aspiration or an esophageal-airway fistula is suspected.

Gastroesophageal Reflux and Hiatal Hernia

Patients with gastroesophageal reflux may undergo surgery because of intractable reflux esophagitis, peptic strictures, or Barrett’s esophagus. With most of these surgical procedures, the crura are dissected, the esophagus is mobilized, the vagus nerves are preserved, the hiatal hernia is reduced, the diaphragm is repaired, and the intra-abdominal esophagus is restored. A variable portion of gastric fundus is usually wrapped around the proximal stomach.

Normal Postoperative Appearances

In a Nissen fundoplication, the gastric fundus is loosely wrapped 360 degrees around the proximal stomach to create an antireflux valve. The Nissen fundoplication wrap normally appears as a 2- to 3-cm fundal mass, with a smooth contour and surface ( Fig. 27-3 ). If the patient drinks barium in a recumbent, steep oblique, or lateral position, the lumen is shown to pass through the center of the fundoplication wrap. The smooth symmetric wrap and its consistent relationship with the lumen readily differentiates a fundoplication wrap from a true tumor in the fundus.

In a Belsey Mark IV repair, the gastric fundus is sutured to the intra-abdominal esophagus, creating an acute esophagogastric junction angle (angle of His); a 270-degree fundoplication wrap is then created. The gastric wrap of a Belsey Mark IV repair produces a smaller defect than a Nissen fundoplication. Two distinct angles are formed passing through the 270-degree fundoplication. The intra-abdominal esophagus has a shallow upper angle where the esophagus, fundus, and diaphragm are sutured together and a lower angle where the stomach is pulled upward toward the esophagus.

A less than circumferential wrap may be made anteriorly or posteriorly, especially in patients with esophageal dysmotility and poor esophageal clearance. Wraps may be made loosely ( Fig. 27-4 ), especially if the surgery is performed laparoscopically. Knowledge of the exact surgical technique performed is helpful for radiologic interpretation.

Complications

Complications related directly to surgery include pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum. Acute hemorrhage usually arises from the short gastric vessels ligated at surgery or is related to operative injury of the spleen or liver. Instrumental perforation of the esophagus or stomach may not be detected during surgery and may lead to a left upper quadrant abscess. Late esophageal perforation may be caused by ischemia or diathermy injury.

Obstruction

During the early postoperative period, edema of the fundoplication wrap may cause transient dysphagia. This complication may be manifested on esophagograms by a large, smooth fundal mass associated with smooth, tapered narrowing of the intra-abdominal esophagus and delayed emptying of contrast material ( Fig. 27-5 ). The edema usually subsides within 1 to 2 weeks; a follow-up esophagogram demonstrates a much smaller defect in this region because of the normal fundoplication wrap.

Some patients may have persistent narrowing at the fundoplication, causing dysphagia or the so-called gas bloat syndrome, with upper abdominal fullness and an inability to belch after meals. Patients may also complain of an inability to vomit and increased flatulence. In such cases, esophagograms may demonstrate fixed narrowing of the lumen as a result of a tight fundoplication wrap ( Fig. 27-6 ) or excessive closure of the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm. It is sometimes difficult to distinguish a persistent reflux-induced distal esophageal stricture from a tight wrap. Examination of the preoperative images is helpful.

Recurrent Hiatal Hernia and Gastroesophageal Reflux

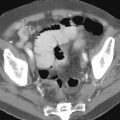

Complete disruption of the fundoplication sutures and crural repair is manifested radiographically by a recurrent hiatal hernia and gastroesophageal reflux, without visualization of the fundoplication wrap ( Fig. 27-7 ). Partial disruption of the fundoplication sutures may be manifested by a partially intact wrap associated with one or more outpouchings from the gastric fundus ( Fig. 27-8 ) or by an hourglass appearance of the stomach as the fundus slips through the fundoplication. An hourglass stomach may also be caused by inappropriate placement of the fundoplication around the gastric body. Finally, disruption of the diaphragmatic sutures (but not the fundoplication sutures) may result in a recurrent hiatal hernia, with continued demonstration of an intact fundoplication wrap ( Fig. 27-9 ). A paraesophageal hernia may occur at diaphragmatic repair breakdown ( Fig. 27-10 ).

Benign Strictures

Benign esophageal strictures may be treated by various surgical and nonsurgical procedures, including esophageal bougienage, fluoroscopically controlled balloon dilation, endoscopically placed esophageal stents, and esophageal replacement with a gastric tube, jejunal graft, or colonic interposition. The site, extent, and cause of the stricture affect the therapeutic choice. Peroral balloon or endoscopic dilation of strictures under fluoroscopic guidance is an effective alternative to esophageal bougienage. This procedure has a lower risk of perforation and a longer symptom-free interval than esophageal bougienage.

Surgery is usually required for the treatment of lye strictures. Esophageal replacement surgery may also be performed on patients with intractable strictures caused by gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree