and A. Orlando Ortiz2

(1)

Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine, Royal Oak, Michigan, USA

(2)

Department of Radiology, Winthrop-University Hospital, Mineola, NY, USA

Keywords

Infection preventionInformed consentPatient, evaluationPatient, historyPatient, safetyPatient, screeningPatient, verificationPatient, periprocedural carePatient, postoperative carePercutaneous biopsy, spinePercutaneous biopsy, ribUniversal protocolThe original version of this chapter was revised. An erratum to this chapter can be found at DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-43326-4_12

An erratum to this chapter can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43326-4_12

Learning Objectives

- 1.

To understand the critical role that proper patient preparation plays in image-guided percutaneous spine or rib biopsy

- 2.

To optimize patient screening practices

- 3.

To improve patient safety by the appropriate application of key patient safety initiatives such as “time-out,” hand hygiene, and patient education

1.1 Introduction

Performing a biopsy or biopsies of a spinal, paraspinal, or rib lesion can be a complex procedure. What initially may seem like an innocuous spine or rib biopsy can, without appropriate preparation, quickly become a difficult, if not complicated, procedure. Proper strategic planning before, during, and after the procedure will increase patient safety, patient comfort, and patient satisfaction as well as increase the efficiency and efficacy of the biopsy process. This starts with a thorough review and discussion of the request for the biopsy and a review of the indications for the procedure. Communication between the operator performing the procedure and both the patient and the referring clinician is an important part of the process. The patient and/or the patient’s representative should understand the reason for the procedure, the steps necessary for patient preparation, the potential risks of the procedure, and the expected post-procedure care and recovery process. The patient’s medications may have to be adjusted or held. Patient-specific information may alter plans for patient positioning or sedation/analgesia. From the perspective of the patient, a spine or rib biopsy is an invasive procedure, and the operator is acting as their physician advocate when not just performing the procedure but also when considering the biopsy request, planning the biopsy procedure, recovering the patient and following up with the patient, and referring and consulting clinical services.

1.2 Before the Procedure

1.2.1 Prescreening and Scheduling

The request for a biopsy may come via the electronic medical record, a written prescription, or verbally either in person or by telephone. A verbal request must be confirmed with an electronic or written request. The request should identify the patient with at least two identifiers which usually include name and either date of birth or a unique medical record number. It is useful to have multiple ways to contact the patient when scheduling an outpatient. Requesting the patient’s home, work, and cell phone numbers improves the ability to contact the patient both before and after the procedure. All staff should be reminded that personal health information should not be left on an answering machine, voice mail, or other unsecured communication. Contacting inpatients is usually more easily accomplished although contact information may be needed for the patient’s representative if the patient is not capable of providing the needed clinical information, understanding the procedure, or providing informed consent.

It is extremely useful to have contact information for the requesting physician if questions arise about the appropriateness of the procedure, safety of the procedure, the need to adjust medications, or to suggest another study or procedure if indicated. The request should include the clinical history (signs/symptoms/ICD 10 code) providing the medical indication for the biopsy as well as any other pertinent medical information. Information about the study that prompted the biopsy request including the dates of the prior study and the type of study such as a CT, MRI, ultrasound, radiograph, bone scan, or PET scan should be included. If the study was from outside of the medical practice requested to perform the biopsy, it should be made available for review. The level to be biopsied should be indicated although this may be adjusted after review of the history and imaging studies. Additional information such as if the referring physician thinks the patient will need general anesthesia for the procedure is also acquired.

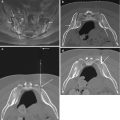

The operator who is to perform the biopsy should review the study that prompted the request for the biopsy as well as all pertinent clinical information. A careful review of the patient’s prior imaging studies is a key prerequisite in the biopsy planning process. It may be determined that the biopsy is not indicated or that there is a safer lesion to biopsy that the referring physician may not be aware of. If it is determined that the lesion should not be biopsied or that a different lesion should be biopsied, communication with the referring physician is essential. Once he/she decides to perform the biopsy, the operator should then determine whether it should be scheduled in CT, fluoroscopy, ultrasound, or MRI (CT and fluoroscopy are most often utilized).

A careful review of the patient’s prior imaging studies is a key prerequisite in the biopsy planning process.

Having experienced personnel involved in scheduling, the procedure is useful after it has been determined that the biopsy is indicated. A brief history is obtained to determine if the patient has any medical conditions that may affect the ability to perform the biopsy. Conditions such as respiratory compromise, seizures, inability to stay in the preferred position, anxiety, or heightened sensitivity to pain may require special planning. The presence of an active infectious process may lead to delaying the procedure if the purpose of the biopsy is not to evaluate the infectious process. Information on allergies is collected and placed in the patient’s medical record.

Biopsy procedures are often elective, but can also be urgently requested. In the case of the former, there is often sufficient time to acquire the appropriate imaging and clinical information to review as part of the biopsy planning process. Additionally, it can be very helpful, especially if the patient is available, to arrange for a pre-procedure consultation with the patient. This is a good opportunity for the operator to review all of the pertinent medical and radiologic information, to examine the patient, to order any necessary laboratory tests, to perform medication reconciliation, and to advise on periprocedural medication adjustments as necessary. Allergies and adverse responses to specific medications should be documented. The latter not only includes oral anticoagulants and antiplatelet medications but also diabetic medications, specific vitamins, and herbal agents. At the time of consultation, the operator may be able to determine which positions the patient can tolerate. Based upon the complexity of the procedure, the patient’s comorbidities, and the patient’s preference, a determination can be made of the type of anesthesia to be used for the biopsy procedure. This is a tremendous opportunity for the patient and their family to develop a healthy relationship with their doctor and to ease fears or concerns regarding the biopsy procedure and the results. The operator can also provide an overview of what to expect just before, during, and after the biopsy procedure. A brief explanation of the procedure, in layman’s terminology, can also help the patient and their family to better understand what will happen. The patient will want to know the risks and benefits of the intended biopsy procedure and will also want to know if there are any other diagnostic alternatives. This information is part of the informed consent process, and depending on the regional regulations, it may be possible to obtain the informed consent at the time of the consultation. This information can be expeditiously reviewed with the patient and their family at the time of the procedure. At the time of the consultation, a patient information guide, if available, can be given to the patient; many patients are often anxious and forget what they were told – these educational guides help to remind them and ease their anxiety levels (RadiologyInfo.org: Biopsies – Overview 2016). Printed patient instructions are also helpful for the very same reason (see sample instructions – Spine Biopsy: Pre-Procedure Patient Instruction Sheet).

In an urgent care setting, the patient may present directly for the biopsy procedure, as a direct outpatient referral or as an inpatient. A concise evaluation should be performed with respect to image review, medical evaluation, and acquisition of the pertinent laboratory parameters. As informed consent for the procedure will be required, this can be the operator’s opportunity to explain the procedure and answer any questions. The medication history is reviewed with the patient. Anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents are the most common medications to affect scheduling of the procedure (refer to Chap. 2). If the biopsy is being performed for evaluation of a potential infectious process, the patient should preferably not be on antibiotics as these can potentially result in a false-negative or nondiagnostic biopsy result. The procedure is explained to the patient or the patient’s representative in sufficient detail to ensure that the nature of the procedure is understood. This conversation is not meant to replace the informed consent that is obtained before the procedure by a member of the team who is credentialed to perform the biopsy. This consultation prevents patients from coming into the radiology department thinking that they are having a radiograph and allows for the patient to schedule time off from work for both the procedure and recovery and to have transportation arranged. Depending on the planned sedation, the patient will be instructed to be NPO for at least 4 h, and if general anesthesia or deep sedation is planned, the patient is NPO for at least 8 h unless there is a contraindication. This may require management of insulin therapy or oral diabetic medications in patients with diabetes. Patients with diabetes will also require glucose monitoring before and after the procedure. If a diabetic patient is using an insulin pump, then this device should be disconnected prior to the procedure. The insulin pump can be reconnected in the recovery area.

Most procedures are performed on an outpatient basis. Complex procedures may require a short stay admission and occasionally an inpatient admission, particularly on medically fragile or complex patients. The admitting service may be the performing operator, radiology if radiologists are privileged for admissions, the referring service, or a hospitalist service. If another service is admitting the patient, the individual who is to perform the procedure should be available for consultation.

1.2.2 Informed Consent

Informed consent should be obtained from the patient or the patient’s representative before the procedure. This typically occurs on the day of the procedure for outpatients but may be obtained during a clinic visit before the day of the procedure. Inpatients are often consented the day before the procedure or the day of the procedure. The informed consent includes a discussion of the procedure, indication for the procedure, risks, potential complications, alternatives to the procedure, and expected benefits of the procedure (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1

Benefits and risks of percutaneous image-guided spine or rib biopsy

Benefits | |

Identify and characterize the abnormality that has been previously identified | |

Assess for neoplasm | |

Assess for infection | |

Assess for inflammation | |

Assist in pretreatment planning | |

Avoid, as much as possible, the possibility of an open biopsy | |

Risks | |

Bleeding | Neural injury |

Infection | Pneumothorax |

Pain | Solid organ injury |

Nondiagnostic biopsy | |

Contrast agent reaction (when intravenous iodinated contrast agent is used) | |

Anesthesia (respiratory compromise, cardiovascular collapse, death) | |

When contemplating an image-guided percutaneous spine or rib biopsy, the operator should be clearly able to answer in the affirmative to the question: will the results of this procedure significantly impact on the clinical management of the patient? As shown in Table 1.1, this procedure should have a well-defined benefit. Image-guided percutaneous spine or rib biopsy is associated with a very low complication rate. The majority of these complications are related to injury caused by the needle device. Fortunately, with appropriate image guidance and with proper pre-procedure planning and patient selection, these complications can be kept to a minimum (Ortiz et al. 2010). The possibility of a nondiagnostic biopsy, albeit uncommon, should be discussed with the patient. This may necessitate a repeat percutaneous biopsy or an open biopsy by a surgeon. The patient should understand that there are alternatives, though to a certain extent less desirable, to performing image-guided percutaneous spine or rib biopsy. The competing alternative, open biopsy, is more invasive and more labor and equipment intensive and will carry a similar profile of complications with a somewhat higher complication rate and greater post-procedure morbidity and recovery time. Many of these patients are already being sent to you by spine or thoracic surgeons in order to have this procedure – so this portion of the conversation with the patient moves quickly. In terms of the other alternatives, many patients will want an answer to their medical condition and are therefore eager and willing to undergo the biopsy procedure as opposed to waiting months, or what they perceive is an eternity, for continued imaging surveillance and laboratory testing. Lastly, clinicians will be reluctant to subject their patients to empiric treatments, which also carry risks and complications, and will want a definitive diagnosis before commencing with a given treatment plan.

The biopsy alternatives that can be discussed with the patient include:

- 1.

Percutaneous biopsy

- 2.

Open biopsy

- 3.

Continued imaging surveillance of the detected abnormality

- 4.

Empiric therapy (e.g., broad-spectrum antibiotics for suspected infection)

If anesthesiology is providing sedation or anesthesia, a separate consent is obtained by the anesthesiologist. If the person performing the procedure is responsible for sedation, it is included with the procedure consent. The patient should be given an opportunity to have all questions answered. Many institutions have a recorded consent line that is made part of the permanent record if consent cannot be obtained from the patient’s representative in person. Emergent procedures can be performed without consent if there is great risk to the patient and consent cannot be obtained. It is important to follow both hospital policies and local laws when making this determination. There should be documentation from both the physician performing the procedure and the physician caring for the patient that the procedure is emergent and that there is significant risk to delaying the procedure. This is a rare occurrence, and only a very small percentage of biopsies will fall into this category. The signed consent form should be witnessed at the time of the consent process, and this can be performed by another staff member.

1.3 At the Time of the Procedure

1.3.1 Patient Sedation

Sedation should be planned based upon the patient’s medical condition and comorbidities and the complexity of the procedure (Mueller etal. 2000). Additionally, a patient’s preference may factor into this decision. The Joint Commission and the American Society of Anesthesia (ASA) describe sedation as mild, moderate, deep, and general anesthesia (American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists 2002). The patient’s cardiovascular function, airway, and ventilation are not impaired when administering minimal sedation. Moderate sedation is greater sedation than minimal, but the airway does not require protection. The patient may require greater verbal or tactile stimulation to respond to questions than with minimal sedation. Physicians must be credentialed by their institution in moderate sedation to administer this level without an anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist present. A staff member other than the one performing the procedure should be responsible for monitoring the patient while under moderate sedation. The levels of sedation are a continuum, and the intended moderate sedation may unexpectedly become deep sedation. Staff should be trained and equipment available to handle the possibility of deeper sedation. Deep sedation and general anesthesia are best managed by an anesthesiologist because of the greater likelihood of need for airway protection and greater support of cardiovascular function. Moderate or greater sedation requires a patient evaluation that includes documentation of the ASA physical status:

- I.

Normal healthy patient

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree