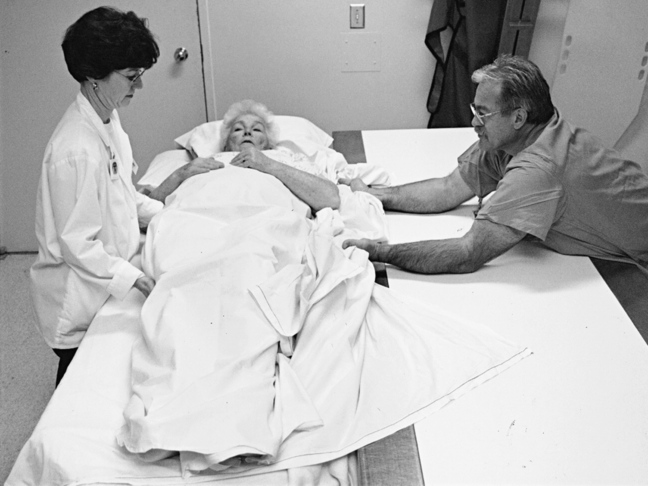

2 After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to perform the following: • Distinguish between beneficence and nonmaleficence. • Identify the four conditions used to assess the proportionality of good and evil in an action. • Demonstrate an ability to make appropriate decisions by applying the principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence. • Identify medical indicators involved in imaging. • State the imaging professional’s role in doing good and avoiding evil. • Provide patients with the knowledge necessary to ensure their participation in decision making. • Identify and define the legal concept of standard of care. • List the many sources of standards of care. • Define negligence, medical negligence, and res ipsa loquitur. • Identify methods to decrease risk, including documentation, technical detail issues, radiation protection, and safety. • Identify and justify which information is appropriate and inappropriate for documentation. This good encompasses proper behavior within “law, custom, relationship, and contract.”1 State and federal laws, which presumably have been based on moral and culturally virtuous processes, may give the health care professional defined guidelines within which to do good as society sees matters. For example, society perceives caring for sick people and supplying high-quality imaging services as inherently good. Custom further helps define good behavior based on repeated patterns within the society. Relationships between individuals, individuals and institutions, and individuals and society also contribute to a definition of good within a society. In addition, the contractual process may indicate an individual’s conception of a good act. 1. The action must be good or morally indifferent in itself. For example, a proposed imaging procedure must help the patient or at least not cause harm. 2. The agent must intend only the good effect and not the evil effect. That is, the imaging technologist must intend for the imaging to aid in the health care process, not injure the patient or cause pain. 3. The evil effect cannot be a means to the good effect. This condition may be complicated for the imaging technologist. The patient may believe the imaging procedure to be an evil effect; however, to gain a diagnosis, or good effect, the patient may have to undergo an unpleasant examination. 4. Proportionality must exist between good and evil effects. The good of the procedure must at least balance with the unintended pain or discomfort. To conform to the principle of proportionality, “the action should not infringe against the good of the individual. There also has to be a proportionate good to justify the risk of an evil consequence.”1 The following questions may be used to define proportionality: • Are alternatives with less evil consequences available? Might another procedure produce the same diagnosis with less pain? For example, might magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) be used instead of mammography? • What are the levels of good intended and evil risked? What will be gained from the procedure? For example, can a contrast media fluoroscopic examination of a first-trimester pregnant woman be justified? • What is the probability that the good or evil intended will be achieved, and what action and influence do the health care team and patient have? What gains to the patient are possible, and will the imaging specialist have to convince the patient or surrogate that the patient should undergo the procedure? Although beneficence and nonmaleficence are both important considerations in patient autonomy, they differ in the way they are practiced. Beneficence is an active process, whereas nonmaleficence is passive (Table 2-1). This difference is evident in the scenario on p. 32. TABLE 2-1 DIFFERENCES BETWEEN NONMALEFICENCE AND BENEFICENCE From Creasia J, Parker B: Conceptual foundations of professional nursing practice, ed 2, St Louis, 1996, Mosby. Jansen, Siegler, and Winslade2 provide six points to consider when dealing with issues of beneficence and nonmaleficence. With some modifications to suit imaging situations, these are the points: 1. What is the patient’s medical problem (what brings the patient to the imaging department)? History? Diagnosis? Prognosis? 2. Is the problem acute? Chronic? Emergent? Reversible? How will this affect the imaging procedure? 3. What are the goals of the treatment or imaging procedure? 4. What are the probabilities of a successful imaging exam? 5. What are the plans in case of therapeutic failure or the inability to complete the exam? 6. In sum, how can this patient benefit by the medical and imaging care? How can the imaging professional avoid harm to the patient? For imaging professionals, justice, or the principle of fairness, requires the performance of an appropriate procedure only after informed consent has been granted. Informed consent is permission, usually in writing, given by a patient agreeing to the performance of a procedure. (Issues of informed consent are discussed more fully in Chapter 4.) Conflicts among beneficence, nonmaleficence, and autonomy (the state of independent self-government) may arise during consideration of principles of justice. The general belief in the right to health care brings beneficence and nonmaleficence into conflict with autonomy and justice. Although most people believe that the good of health care should be available to all, health care resources are limited and hard decisions must be made about their allocation. Limited resources reduce the overall quality of care and may lead to less avoidance of evil. When quality of health care is reduced, the patient’s autonomy suffers from loss of freedom of choices. When choices are limited, the obligations of the patient and health care giver may conflict with resources and justice for the patient (Figure 2-1). The performance of good and the avoidance of evil often come into conflict when medical indication principles or the proportionality of consequences is judged by the health care provider. The medical indication principle states that, “granted informed consent, the physician should do what is medically indicated such that from a medical point of view, more good than evil will result.”1 Verbal and written contractual agreements help provide patient autonomy. Patients requiring imaging services enter into contractual agreements when they agree to enter a hospital and undergo a series of diagnostic imaging studies. Usually such contracts take the form of blanket statements of informed consent. They are general agreements; other processes of informed consent may be required as specific procedures are scheduled. The processes of informed consent and the procedures employed in providing it are discussed at length in Chapter 4. Surrogate obligations present another area of conflict. The interactions among patient autonomy, beneficence, and nonmaleficence become even more complex in these situations. If the patient is incompetent, either the best interests of the patient or the rational choice principle should be used. The rational choice principle “commands that the surrogate choose what the patient would have chosen when competent and after having considered all available relevant information and the interests of the relevant others.”1 In a determination of the best interests of the patient, the proportionality between good and evil may be different for patient and surrogate; this may interfere with patient autonomy. In this situation the surrogate must consider the patient’s and perhaps significant others’ attitudes regarding good and evil consequences. The imaging professional must be aware of the obligations to do good and avoid harm. Every imaging procedure has the potential to harm the patient; invasive procedures, radiation, and equipment malfunction all pose dangers to the patient. Maintaining a high quality of patient care and technologic skills helps ensure that procedures achieve good for the patient, and practicing protective measures aids in the avoidance of harm (Figure 2-2). Each imaging professional must be responsible for daily contact with patients undergoing diagnostic health care procedures. The legal standard is the degree of skill or care employed by a reasonable professional practicing in the same field.3 Lack of training or experience is not an excuse for the failure of a health care professional to perform a duty to the patient adequately. For example, imaging professionals working as nuclear medicine technologists are held to the same standard of care as trained and certified nuclear medicine technologists. If the appropriate standard of care is violated, liability may be imposed on both health care professionals and medical facilities. Practice standards, educational requirements, and curricula developed for the medical imaging sciences all help to establish the standard of care to which imaging professionals must hold themselves. The practice standards for health care specialists are set forth by that discipline’s national professional organization. Practice standards are important because they are recognized as the authoritative basis of a profession. Specific practice standards exist for each subspecialty of imaging, including cardiovascular-interventional technology, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, mammography, nuclear medicine, radiation therapy, radiography, and sonography.4 These standards may be found on the website of the American Society of Radiologic Technologists (www.asrt.org). The practice standards may be used to define what radiologic technologists do and how they do it. For example, health care facilities use professional standards to develop job descriptions, departmental policies, and performance appraisals. If there is a question as to whether an activity falls within the professional duties of the radiologic technologist, a radiology manager may consult the practice standards. Practice standards may also be used to hold the radiologic technologist to a certain standard of care. In the case of medical malpractice or negligence, a lawyer may use the practice standards to establish the generally accepted standard of care and show whether the professional met that level of care.4 Standards for accreditation for educational programs in radiologic sciences as defined by the Joint Review Committee on Education in Radiologic Technology (effective January 1997)5

Principles of Beneficence and Nonmaleficence

ETHICAL ISSUES

PROPORTIONALITY

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN BENEFICENCE AND NONMALEFICENCE

Nonmaleficence

Beneficence

Goal is to do no harm

Goal is to do good

Achieved through passive omission

Achieved through active process

Primary responsibility of the health care provider

Secondary in importance to nonmaleficence

MEDICAL INDICATIONS INVOLVING PRINCIPLES OF BENEFICENCE AND NONMALEFICENCE

JUSTICE

CONTRACTUAL AGREEMENTS

SURROGATE OBLIGATIONS

Imaging Professional’s Role

LEGAL ISSUES

STANDARD OF CARE

Professional Standard of Care

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Principles of Beneficence and Nonmaleficence