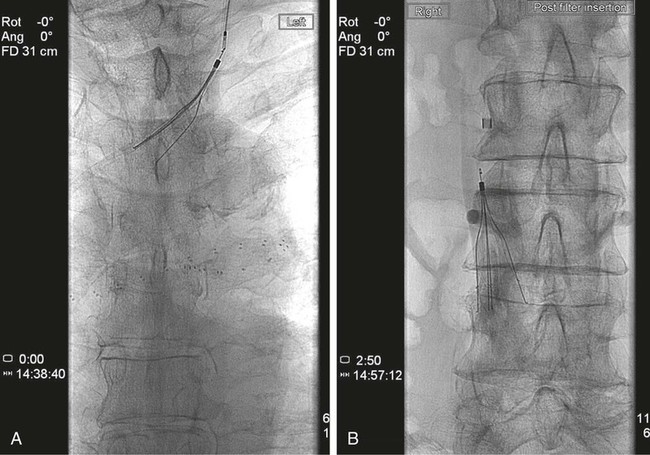

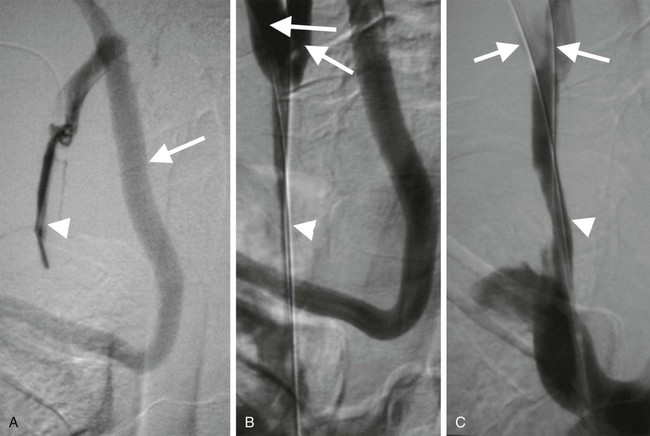

The National Institute of Clinical Excellence has recommended that ultrasound guidance should be used when inserting elective central venous lines.1 There is clear evidence that using imaging guidance increases success rates and reduces complications associated with jugular and subclavian vein puncture. Most of these routine procedures do not require interventional radiologic input, but interventional radiologists become indispensable in cases where central venous access is difficult, as is often the case in hemodialysis and cancer patients.2 Venous access is the starting point for a large number of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in the systemic and portal venous circulations. Table 29-1 lists typical indications. TABLE 29-1 Interventional Procedures Requiring Venous Access It is sometimes necessary to predilate a stenosed or occluded vein prior to passage of a line (Fig. 29-1). Stents are generally unnecessary, however, if access rather than patency is the desired outcome. Several considerations may be relevant when planning the optimal approach for venous access. The general adage that the shortest, straightest route is best often applies, but this should be weighed against possible disadvantages of choosing a particular site. Typical approaches are outlined in Table 29-1, but there are also some esoteric routes typically reserved for cases wherein all other options have failed. These include utilizing collateral veins, transhepatic, translumbar, or transrenal access to the systemic veins and transsplenic or transmesenteric access to the portal venous system. There are occasions when dual access is helpful, especially when the most direct route is through a small vessel or via an artery. Central venous access is the starting point for many procedures (see Table 29-1). The most common points of access are the internal jugular and subclavian veins. The jugular vein is superior to the subclavian vein because it is less prone to symptomatic thrombosis.3 The right internal jugular vein also provides the shortest, straightest route and is the first-choice point of access. The left jugular approach is often possible, but it is important to be aware of any sharp bends in the mediastinum that may result in kinking of sheaths (Fig. 29-2). It is prudent to check the manufacturer’s instructions for use; there are sometimes caveats to using the left jugular approach for this reason.

Principles of Venous Access

Clinical Relevance

Indications

Procedure

Typical Approach

Diagnostic

Venography

Appropriate peripheral vein

Venous sampling

Femoral vein

Pulmonary angiography

Femoral vein

Therapeutic—Systemic

Venous angioplasty, stenting, and thrombolysis

Appropriate peripheral vein

IVC filter placement

Jugular vein

Tunneled central line insertion

Jugular vein

Repositioning/stripping of lines

Femoral vein

Management of SVCO/IVCO

Jugular vein

Transjugular liver biopsy

Jugular vein

Varicocele and ovarian vein embolization

Femoral vein

Varicose vein ablation

Appropriate peripheral vein

Therapeutic—Portal

TIPS

Jugular vein

Portal vein embolization

Transhepatic

Post transplant portal vein intervention

Transhepatic

Equipment

Ultrasound

Angioplasty Balloons and Stents

Technique

Anatomy and Approach

Central Venous Access

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Principles of Venous Access