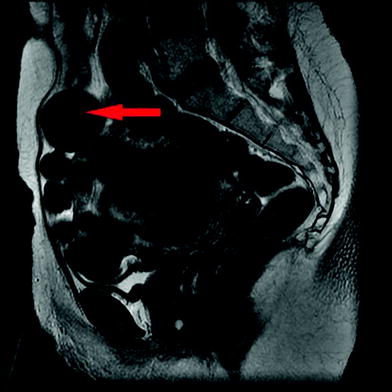

Fig. 1

Hematoma formation

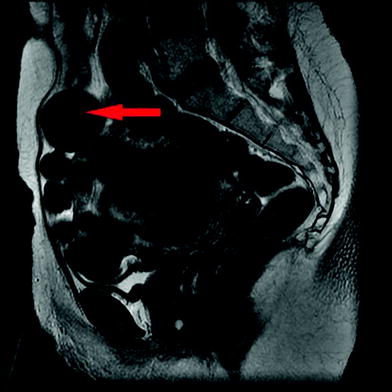

Fig. 2

Ultrasound of pseudo aneurysm

Which pseudo aneurysms require treatment? Physicians will not commonly treat a pseudo aneurysm <2 cm which is stable in size. If expectant management is elected the patient must be examined again within 48 h to confirm that the area is not expanding. A pseudo aneurysm seldom requires surgical management. Instead thrombin will be injected under ultrasound guidance into the pseudo aneurysm to clot off the area of concern. Follow-up examination after injection is good practice to confirm the efficacy of treatment.

2.2 Leg Pain

Just as particles may enter the gluteal arteries as a result of nontarget embolization, some particles may reflux around the end of the catheter and enter the common femoral artery. We will routinely order doppler studies of the arteries and veins of both legs when a patient complains of leg pain. Even in the absence of a swelling in the common femoral artery, pain must be evaluated.

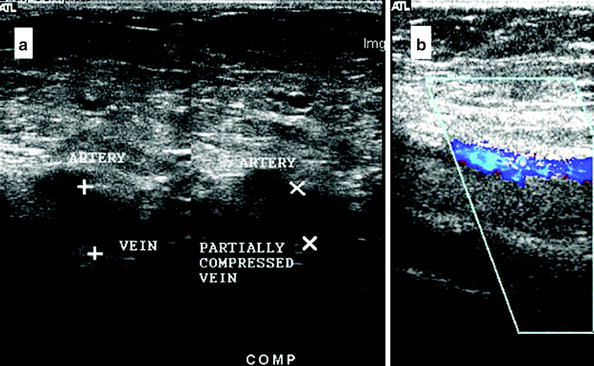

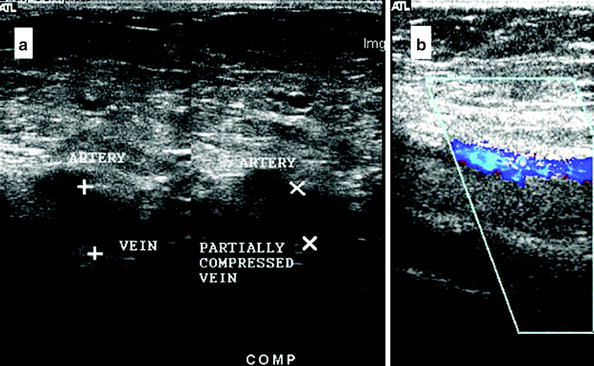

The possibility of venous thrombus disease should be considered in all patients (Czeyda-Pommersheim et al. 2006). We have favored use of an arteriotomy closure device in our patients, although some authors question the efficacy of such device. Early ambulation after UAE goes a long way to preventing thrombotic disease. If a thrombus is discovered in the femoral vein, immediate therapy is indicated. Usual therapy is anticoagulation with heparin, followed by transition to coumadin. Unless there is evidence of pulmonary emboli, or high risk factors for the development of this complication, we have not placed caval filter devices (Fig. 3). Emboli must be carefully ruled out, proving to be a fatal postembolization problem on a few occasions (Hamoda et al. 2009).

Fig. 3

a Ultrasound image showing presence of a large clot, vessel walls not compressible with applied pressure b Doppler shows blood flow through artery (blue) but not through vein

Operators must be able to recognize dissections and punctures of arteries. We will not discuss management of these complications, as they are hardly unique to UAE procedures. Nonetheless such complications can be life-threatening, and require immediate recognition and treatment. Assuming these studies to be negative pulmonary obstruction and phlebitis should be ruled out. Patients will respond to therapy with exercise, physical therapy, and calcium within a few days.

3 Postembolization Fever

A potential source of fever after UAE is due to pelvic infection. To prevent fever associated with postembolization infection most doctors will use prophylactic antibiotics prior to the procedure as a precautionary measure. The most commonly used prophylactics for surgical procedures include cephalosporins (McDermott et al. 1997), first generation agents having better activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Coverage does not include anaerobes (McDermott et al. 1997).

Prophylactic antibiotics used in UAE typically include cephalosporins such as cefalozin or ceforozine (Spies et al. 2002) or a combination of antibiotics shown effective for use against aerobic and anaerobic bacteria such as gentamicin, ampicillin, metronidazole, or clindamycin (Al-Fozan and Tulandi 2002; Gall et al. 1981). For patients with a penicillin allergy vancomycin is used (Weed 2003). No study has shown that the use of prophylactic antibiotics prevents infection after UAE; however, it is suggested that prophylactic antibiotics reduce the risk of sepsis (Walker et al. 1999). In addition, no studies have shown increased risk based on type of particle used (Rajan et al. 2004). Some suggest the location of leiomyoma as submucosal as an increased risk for septicemia (Al-Fozan and Tulandi 2002).

Postembolization syndrome is a common and important early occurring complication after UAE, first being described as a postembolization problem after liver embolization (Slomka and Radwan 1992). Postembolization syndrome has also been associated with UAE patients (McLucas et al. 1999). The syndrome consists of temperature elevation, pain, and nausea. Leukocytosis is often pronounced. In our experience, early occurrence of embolization syndrome within the first 72 h of the procedure is seldom a harbinger of infection. Nonetheless, we routinely question our patients about other sources of temperature elevation. We place an indwelling Foley catheter for the first 12 h after UAE. Could the patient have a urinary tract infection from this intervention? We also give prophylactic antibiotics to patients for the week following their procedure. Is there a change in bowel movements which could suggest the possibility of c difficile enterocolitis?

Once the fever work-up has excluded other sources of fever, we concentrate our work-up on the pelvis. We will routinely obtain a blood culture for a patient with temperature above 100.6 °F. We also will image the pelvis with a computed tomography study of that area including intravenous contrast. Following UAE we routinely see small amounts of air within the uterus (Fig. 4). Onset of symptoms later than 36 h post-UAE is more worrisome than onset prior to 36 h. One circumstance which will compel us to hospitalize a patient is increasing rather than diminishing pain (Table 1). The vast majority of our patients require no more narcotic management after 48 h following UAE. If pain is increasing and associated with fever, we are likely to admit the patient for further evaluation and intravenous antibiotic therapy (Nott et al. 1999). Once in the hospital setting management will depend on physical examination. Peritoneal signs will push a decision for surgery. Another worrisome sign will be rising rather than falling leukocytosis in the face of appropriate antibiotic choice and duration. Repeat imaging may be useful to demonstrate the direction of care.

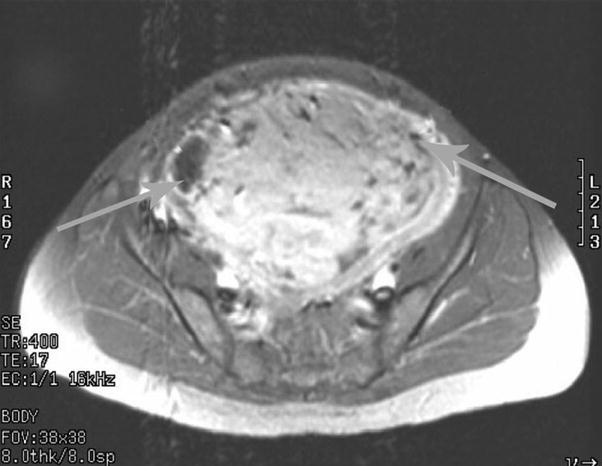

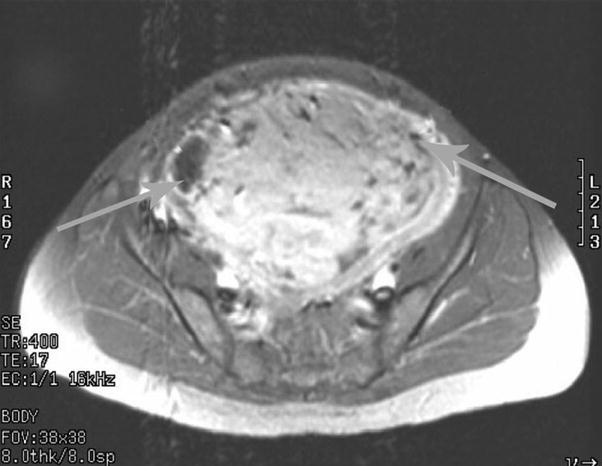

Fig. 4

Postembolization MRI showing normal air pattern in uterus

Table 1

When to hospitalize for postembolization fever

Onset of fever after UAE | Hospitalization | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

<48 h | No | Oral antibiotics |

Pelvic ultrasound or CT scan | ||

48+ h and increasing pain | Yes | Intravenous antibiotic therapy |

Possible surgical candidate |

Fever postembolization can be the result of either infection or postembolization syndrome, the difference being that infection is often associated with a discharge; however, distinguishing the two complications may be difficult (Spies et al. 2002). A discharge several weeks following embolization may simply be the sign of a submucosal myoma being passed. Both postembolization syndrome and infection will involve an increase in white blood cell count.

The first reported death as result of a complication of UAE was due to septicemia (Vashisht et al. 1999). In the case of a septic uterus hysterectomy is necessary. The rate of hysterectomy as a result of pelvic infection following UAE is <1 % (Walker and Pelage 2002). Early treatment of postoperative pelvic infections can prevent septicemia and more serious infections, and generally involves intravenous antibiotic treatment and hospitalization for a day or less.

Choice of antibiotics for coverage of febrile episodes after UAE will often be made in consultation with an infectious disease consultant based on the type of pathogen present. Treatment of infections of the female genital tract has focused on the prevalence of mixed anaerobic and aerobic bacterial infections, anaerobes generally outnumbering aerobic bacteria (Sweet 1981). The bacteria most associated with initial stages of infection are gram-negative facultative bacteria such as E. coli (Spies et al. 2002), suggesting that the use of prophylactic antibiotics may destroy gram-positive organisms but lead to a proliferation of gram-negative organisms (Walker et al. 1999). In addition, anaerobic bacteria such as B. fragilis are typically found in secondary phases of intraabdominal abscesses (Sweet 1981). For penicillin resistant bacteria such as B. fragilis, the antibiotics used for treatment include intravenous metronidazole, clindamycin (Gall et al. 1981) or cephoxitin due to broad range coverage for both anaerobic and aerobic bacteria. The use of antibiotics for a variety of organisms has been shown to be more effective in terms of recovery and incidence of severe infections (Sweet 1981). The use of single antibiotic therapy for polymicrobial obstetrical infections such as clindamycin, ticarcillin, and chloramphenical are as effective as compared to a multiantibiotic approach (Faro et al. 1982). Typically, while waiting for culture results we will choose a broad spectrum second or third generation cephalosporin.

An evolving abscess is often not clear on any kind post-UAE imaging, however, we have had some cases where the abscess within the myoma is obvious (Fig. 5). In such cases surgery is indicated. We have on many occasions removed necrotic myoma, leaving behind normal endometrium and other pelvic structures. Seldom is hysterectomy indicated. Having said this, bacteria often remain behind after myomectomy, requiring aggressive postoperative antibiotic therapy. To reduce the risk of bacterial infection post procedure it may be beneficial to extend the duration of time that antibiotics are given post procedure, especially in patients with a large or submucosal leiomyoma because these myomata are more susceptible to bacterial development post UAE (Brunereau et al. 2000). Infection is possible, so delayed fever post procedure should be carefully clinically monitored and examined via cross sectional imagining of the pelvis and antibiotic therapy depending on the results of the imaging and testing (Goodwin et al. 1997). If monitored early, surgical treatment of infections can be avoided.

Fig. 5

Air levels within myoma suggest abscess formations

3.1 Particle Load

Patients experience necrosis of myomata at different rates. We have tried to limit the particle load given to patients with large uterii to limit the possibility of rapid necrosis and abscess formation. The possibility of not accessing the uterine artery again must be weighed against the possibility of early necrosis and abscess formation. We often begin with 500 μ PVA particles, moving rapidly to a vial of 700 μ particles, followed by 1,000 μ particles, and even larger if necessary. Higher particle load and higher numbers of PVA vials used are associated with higher levels of peak systolic velocity (McLucas et al. 2002), which can be evaluated pre-embolization using Doppler flow sonography (Fig. 6). In addition, we are not hesitant to place a coil in one of the uterine arteries of patients with large uterii. Total uterine volume is calculated using the largest measurements in the anteroposterior, longitudinal, and transverse planes in the formula for a prolate ellipse (McLucas et al. 2002). Particle load is calculated by dividing the volume of uterus by the number of vials of PVA particles used. We have also used pledglets of gelfoam to occlude the arteries of patients with large myomata.

Fig. 6

Right body of the uterus, high Doppler flow shown by yellow, orange, blue, white

Another point to remember in management of the post-UAE patient with fever is that if a patient defervesces in the hospital, and is judged a candidate for outpatient oral therapy, she is still someone who can develop an abscess and require surgery. The patient must be followed up at least weekly, if not twice weekly with in-person visits. Worrisome signs include return of high pain levels and presence of malodorous vaginal discharge.

In summary, early onset of temperature within 48 h of embolization augers for a benign postembolization syndrome. These patients may be often managed as an outpatient, on oral antibiotics, after a reassuring pelvic ultrasound or CT scan. They will require frequent visits, at least weekly, to confirm the benign diagnosis, and rule out sepsis. Late occurring temperature elevations >7 days post procedure and accompanied with an increased pain level require hospitalization, aggressive intravenous antibiotic therapy, and are possible surgical candidates.

4 Hysterectomy Following Embolization

Hysterectomy is required infrequently postembolization. In a study of 1,797 patients from the Fibroid Registry of Outcomes Data, 2.9 % of women were found to require hysterectomy 1 year following uterine artery embolization (Spies et al. 2005a, b

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree