Etiology, Prevalence, and Epidemiology

Pulmonary metastases are common—present at autopsy in 20% to 54% of patients with extrapulmonary malignancy. The most common primary sites associated with pulmonary metastases in biopsy series are the breast, colon, kidney, uterus, bladder, melanoma, and head and neck.

Clinical Presentation

Most pulmonary metastases occurring as single or multiple nodules are asymptomatic. When present, symptoms are nonspecific and include cough, hemoptysis, and shortness of breath. The most common clinical manifestation of lymphatic spread of tumor is dyspnea. The dyspnea is typically insidious in onset but tends to progress rapidly. Similarly, the most common symptom of endobronchial metastases is dyspnea; other common symptoms include cough, recurrent infection, and hemoptysis.

Pathophysiology

Pulmonary metastases may occur by hematogenous, lymphatic, or aerogenous spread.

Hematogenous Spread

Most pulmonary metastases spread to the lungs through the arterial system, lodging within small pulmonary arterioles or arteries. In most cases the newly formed tumor extends into the surrounding lung parenchyma, forming a relatively well-defined nodule. Hematogenous metastases are usually bilateral and manifest with randomly distributed nodules in the outer third of the lower lung zones.

Occasionally, hematogenous metastases to the lungs may result in tumor growth only in the vessel lumen and wall without extension into the extravascular tissue. This condition is known as tumor embolism and is seen most commonly in metastatic renal cell carcinoma; hepatocellular carcinoma; and carcinomas of the breast, stomach, and prostate.

Lymphatic Spread

Lymphatic metastases are most often indirect with first hematogenous spread to pulmonary arteries and arterioles with subsequent invasion of the adjacent interstitial space and lymphatics. Less commonly, lymphatic spread of tumor is retrograde from mediastinal and hilar lymph node metastases. Although virtually any metastatic neoplasm can result in lymphatic spread, the most common extrathoracic cell type is adenocarcinoma from breast and gastrointestinal origin, as well as melanoma, lymphoma, and leukemia.

Pathologically, lymphangitic carcinomatosis ranges from a slight accentuation of the interlobular septa and peribronchovascular connective tissue to marked thickening of these structures. Microscopically, neoplastic cells can be present within the lymphatic spaces or in the adjacent peribronchovascular and interlobular interstitial tissue. Edema or a desmoplastic reaction to the tumor can contribute significantly to the interstitial thickening ( Fig. 22.1 ).

Aerogenous Spread

Airway spread of tumor occurs through direct invasion or seeding of the bronchi by tumor, usually from pulmonary adenocarcinoma or bronchial carcinoid, although upper airway malignancies, such as laryngeal carcinoma, can also progress this way. Endobronchial metastases from hematogenous spread are a different entity and are discussed separately.

Manifestations of the Disease

Pulmonary metastases may result in four main types of imaging manifestations: nodules, lymphatic spread, tumor emboli, and endobronchial tumor.

Radiography

Lung Nodules

The most common manifestation of pulmonary metastases consists of multiple nodules, most numerous in the basal portions of the lungs, reflecting the effect of gravity on blood flow. They range in size from barely visible to large masses ( Fig. 22.2 ). The nodules usually are of varying size; although less often, they are approximately equal, suggesting a single shower of tumor emboli. Rarely, nodular deposits are so numerous and of such minute size as to suggest the diagnosis of miliary fungal infection or tuberculosis ( Fig. 22.3 ).

Certain primary neoplasms are more likely than others to produce solitary metastases on radiography, including carcinoma of the kidney, testicle, breast, and rectosigmoid colon; sarcomas (particularly sarcomas originating in bone); and malignant melanoma.

Lymphatic Spread (Lymphangitic Carcinomatosis)

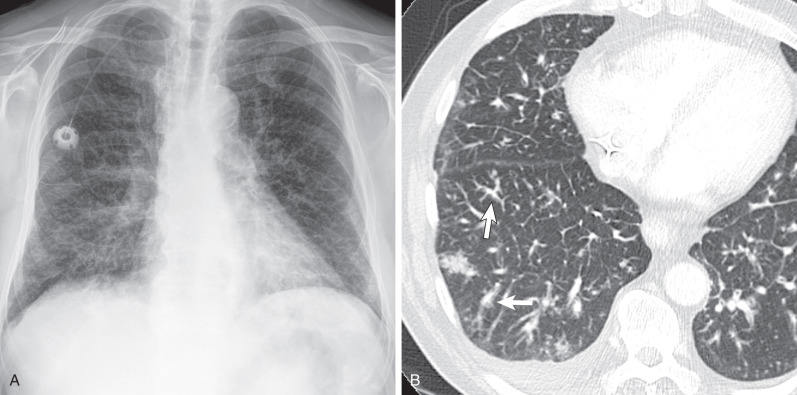

The characteristic radiographic pattern consists of septal lines and thickening of the bronchovascular markings, simulating interstitial pulmonary edema ( Fig. 22.4 ). The linear accentuation sometimes is associated with a nodular component, resulting in a coarse reticulonodular pattern. Hilar and mediastinal lymph node enlargement is seen radiographically in 20% to 40% of patients, and pleural effusion is seen in 30% to 50%. Although characteristic, these findings lack specificity and sensitivity for the diagnosis. The chest radiograph is normal in 30% to 50% of patients who have pathologically proven lymphangitic carcinomatosis.

Computed Tomography

Lung Nodules

On computed tomography (CT), nodular metastases range from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter and are usually of varying size with smooth or irregular margins (see Fig. 22.2B ). The nodules tend to be most numerous in the outer third of the lungs, particularly the subpleural regions of the lower zones, and have a random distribution within the secondary pulmonary lobules. Surrounding ground-glass opacities may result from airspace disease, lepidic growth of neoplasm, or hemorrhage. Metastatic nodules with hemorrhage often manifest the CT halo sign and are most common with choriocarcinoma, melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, angiosarcoma, and Kaposi sarcoma.

Cavitation occurs most often in metastatic squamous cell carcinoma or transitional cell carcinoma but may also be seen with metastatic adenocarcinoma. The wall of a cavitated metastasis is generally thick and irregular ( Fig. 22.5 ), although thin-walled cavities can be found with metastases from sarcomas and adenocarcinomas. Cavitation may also be induced by chemotherapy.

Calcification of metastatic nodules is uncommon and suggests certain primary neoplasms, such as osteogenic sarcoma, mucinous carcinoma, or papillary thyroid carcinoma ( Fig. 22.6 ). Small calcified nodules may mimic benign lesions, especially if eccentric calcification is difficult to ascertain. Calcification can develop at the site of pulmonary metastases that have vanished after successful chemotherapy. This chemotherapeutic effect may manifest with persistent nodules that, on histologic examination, show only necrosis and fibrosis without residual viable neoplastic tissue.

Although hematogenous pulmonary metastases usually result in soft tissue nodules, metastases from adenocarcinoma may spread into the lung along the intact alveolar walls (lepidic growth), in a fashion similar to a primary pulmonary adenocarcinoma. The CT findings of metastases from adenocarcinoma include nodules, consolidation, ground-glass opacities, and nodules with CT halo sign ( Fig. 22.7 ).

Spontaneous pneumothorax resulting from metastatic disease to the lung is rare and should suggest sarcoma, choriocarcinoma, or cavitary metastasis. It has been suggested that the complication is more frequent in patients undergoing chemotherapy. It may also occur before radiographic visibility of metastases.

Solitary pulmonary nodules representing metastatic disease from extrathoracic primaries are rare, accounting for 2% to 10% of solitary pulmonary nodules in some studies. This percentage is based on radiographic findings and with the routine use of CT for screening; solitary metastases are much less common. Many of the nodules identified on CT in patients with extrathoracic malignancies represent granulomas or intrapulmonary lymphoid tissue. Munden and associates determined that 3-month follow-up imaging of patients with extrathoracic malignancies and small, less than 5 mm, incidentally detected pulmonary nodules for the first year and every 6 months thereafter effectively determines the malignant potential of the nodules.

Multiple studies have shown greater than 50% of solitary pulmonary nodules in patients with a history of prior extrapulmonary neoplasia turned out to be primary lung malignancies or benign lesions on surgery or autopsy. The distinction between a new primary and a metastasis has important prognostic and therapeutic implications. Although new chemotherapeutic, and even molecular, therapies continue to develop, pulmonary metastasectomy remains the treatment of choice for most solitary pulmonary metastases. With few exceptions, there are no criteria by which a solitary metastasis can be distinguished definitively from a primary pulmonary carcinoma by imaging. Despite this lack of criteria, certain features of the pulmonary nodule as well as the particular primary neoplasm are associated with an increased probability of one or the other. A solitary nodule in a patient who has a high-grade sarcoma or deeply invasive melanoma is much more likely to be a metastasis than a new primary. A nodule in a patient who has a squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck is more likely a primary pulmonary carcinoma. The time interval between the initial tumor and the appearance of the pulmonary lesion is also important with most metastatic lesions occurring within 5 years of the original diagnosis. The major exception to this rule are carcinomas originating in the breast or kidney, in which metastases can occur many years after the original tumor is identified. Older age and a history of cigarette smoking increase the likelihood that the tumor is primary in the lung. Overall, detection of pulmonary nodules in patients with extrapulmonary malignancy is high, although most nodules are benign, especially if they are smaller than 10 mm in diameter or are less than 10 mm from the pleural surface.

- •

Metastatic pulmonary nodules are usually multiple.

- •

A single nodule is most common in carcinoma of the colon or kidneys and osteosarcoma.

- •

Metastatic pulmonary nodules have smooth or irregular margins and are randomly distributed, with predilection for the peripheral middle and lower lung zones.

- •

Cavitation occurs in 4% of metastases, most commonly in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck or cervix.

- •

Calcification is uncommon and occurs with osteogenic sarcoma; chondrosarcoma; synovial sarcoma; or carcinoma of the colon, ovary, breast, or thyroid.

- •

Small, less than 5-mm pulmonary nodules detected in cancer patients are usually benign. Malignant potential can be determined by looking for growth on 3-month follow-up CT examinations.

Lymphatic Spread (Lymphangitic Carcinomatosis)

Lymphangitic carcinomatosis has a characteristic high-resolution CT appearance, consisting of smooth or nodular thickening of the interlobular septa and peribronchovascular interstitium with preservation of normal lung architecture ( Figs. 22.8 to 22.11 ). The abnormalities may be initially subtle but tend to progress to extensive bilateral disease with associated ground-glass opacities. There is a great deal of overlap between the imaging findings of lymphangitic carcinomatosis and pulmonary edema as the conditions often coexist because of the obstruction of normal lymphatic drainage of fluid from the lungs by the tumor. Pleural effusion is seen on CT in about 30% of cases, and hilar or mediastinal lymph node enlargement is seen in 40%.