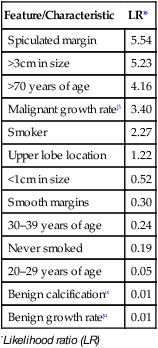

• This is defined as a solitary circumscribed pulmonary opacity with no associated pulmonary, pleural, or mediastinal abnormality • Many are discovered incidentally (but up to 40% may be malignant) • The two primary criteria are the rate of growth (or stability over time) and the attenuation of the nodule – Granular calcification is seen on CT in up to 7% of carcinomas (and can represent either tumour calcification or a granuloma engulfed by tumour) – A mixture of soft tissue and ground-glass attenuation nodules is more likely to be malignant than soft tissue nodules alone Simulants of solitary pulmonary mass* Extrathoracic artefacts Causes of a solitary pulmonary mass* Bronchial carcinoma Radiological features of solitary pulmonary nodules and the likelihood of malignancy *Likelihood ratio (LR) αBenign calcification: diffuse, central, popcorn or concentric µBenign growth rate: a volume doubling time < 1 month or > 2 years (approximately) βMalignant growth rate: a volume doubling time > 1 month or < 2 years (approximately) Adapted from Erasmus et al. Radiographics 2000; 20: 59–66. • SCLC: small (oat) cell carcinoma • NSCLC: non-small cell lung cancer • Risks: tobacco smoke (with a 20–30 fold increased risk) – this has the greatest association with squamous cell carcinomas and the weakest association with bronchoalveolar carcinomas • Asymptomatic (25%): asymptomatic peripheral tumours are more likely to be incidental findings and surgically resectable • Symptomatic: recurrent pneumonia • Paraneoplastic syndromes: inappropriate ADH secretion • Poor prognostic features: hoarseness • The majority are spherical or oval in shape • Ground-glass attenuation is associated with a higher risk of malignancy (and commonly seen with bronchoalveolar carcinoma) • This does not preclude surgical resection (although it adversely affects the prognosis) • CT: assessment is unreliable (with local chest wall pain remaining the most specific indicator) • MRI: this is better than CT in selected cases • Transthoracic ultrasound: this is an accurate technique • 99mTc radionuclide skeletal scintigraphy: this is sensitive (and may detect bone invasion before plain radiography) • CT/MRI indicators: visible tumour deep within the mediastinal fat (mediastinal contact alone is not enough to diagnose invasion) • Criteria for resectability: < 3cm of contact with the mediastinum • Irresectability: tumours obliterating fat planes or showing greater contact than that described above

Pulmonary neoplasms

EVALUATION OF THE SOLITARY PULMONARY NODULE

EVALUATION OF THE SOLITARY PULMONARY NODULE

DEFINITION

it measures < 3cm in diameter

it measures < 3cm in diameter

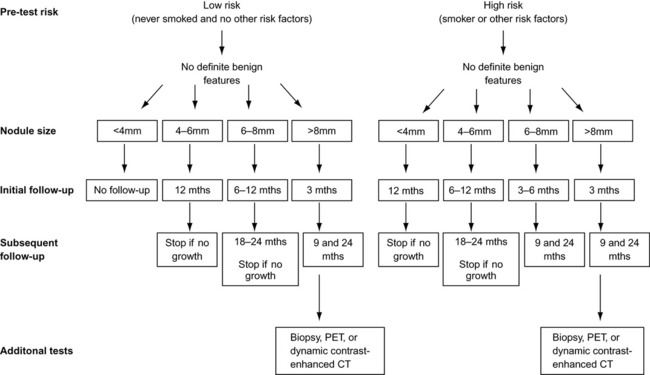

DIFFERENTIATION BETWEEN BENIGN AND MALIGNANT MASSES

the patient’s age is also a significant distinguishing feature (a carcinoma is only seen in < 1% of patients < 35 years old)

the patient’s age is also a significant distinguishing feature (a carcinoma is only seen in < 1% of patients < 35 years old)

Rate of growth/stability over time: benign lesions invariably have a doubling time of < 1 month or > 18 months (bronchoalveolar carcinomas are an exception in that they may have very slow growth rates)

Rate of growth/stability over time: benign lesions invariably have a doubling time of < 1 month or > 18 months (bronchoalveolar carcinomas are an exception in that they may have very slow growth rates)  bronchial carcinomas usually have a doubling time of between 1 and 18 months

bronchial carcinomas usually have a doubling time of between 1 and 18 months

Attenuation/enhancement: a dense central nidus or laminated calcification indicates a granulomatous process (e.g. tuberculosis, histoplasmosis)

Attenuation/enhancement: a dense central nidus or laminated calcification indicates a granulomatous process (e.g. tuberculosis, histoplasmosis)  irregular ‘popcorn’ calcification suggests a hamartoma

irregular ‘popcorn’ calcification suggests a hamartoma  fat is virtually diagnostic of a hamartoma

fat is virtually diagnostic of a hamartoma  a lack of enhancement (<15HU) following IV contrast medium is indicative of benignity

a lack of enhancement (<15HU) following IV contrast medium is indicative of benignity

Size: this is of little diagnostic value

Size: this is of little diagnostic value

Margins: a well-defined mass with a smooth pencil sharp margin is likely to be benign

Margins: a well-defined mass with a smooth pencil sharp margin is likely to be benign  carcinomas typically have ill-defined margins which are irregular, spiculated, or lobulated and may exhibit umbilication or a notch – unfortunately all these features can be seen with benign disease

carcinomas typically have ill-defined margins which are irregular, spiculated, or lobulated and may exhibit umbilication or a notch – unfortunately all these features can be seen with benign disease

Cutaneous masses

Bony lesions

Pleural tumours of plaques

Encysted pleural fluid

Pulmonary vessel

Bronchial carcinoid

Granuloma

Hamartoma

Metastasis

Chronic pneumonia or abscess

Hytadid cyst

Pulmonary haematoma

Bronchocele

Fungus ball

Massive fibrosis in coal workers

Bronchogenic cyst

Sequestration

Atriovenous malformation

Pulmonary infarct

Round atelectasis

Feature/Characteristic

LR*

Spiculated margin

5.54

>3cm in size

5.23

>70 years of age

4.16

Malignant growth rateβ

3.40

Smoker

2.27

Upper lobe location

1.22

<1cm in size

0.52

Smooth margins

0.30

30–39 years of age

0.24

Never smoked

0.19

20–29 years of age

0.05

Benign calcificationα

0.01

Benign growth rateµ

0.01

LUNG CANCER: RADIOLOGICAL FEATURES

LUNG CANCER: RADIOLOGICAL FEATURES

DEFINITION

This originates from submucosal neuroendocrine cells

This originates from submucosal neuroendocrine cells  it rapidly spreads haematogenously and to the lymph nodes

it rapidly spreads haematogenously and to the lymph nodes  it behaves as a systemic disease and is usually disseminated at presentation

it behaves as a systemic disease and is usually disseminated at presentation

Squamous cell carcinomas: arises from the proximal airway epithelium

Squamous cell carcinomas: arises from the proximal airway epithelium

Large cell carcinomas: atypical cells that appear ‘large’ under the microscope

Large cell carcinomas: atypical cells that appear ‘large’ under the microscope

Adenocarcinomas: arising from the bronchial glands

Adenocarcinomas: arising from the bronchial glands

Bronchoalveolar carcinoma: an adenocarcinoma subtype arising from the alveoli and adjacent small airways (probably from type II pneumocytes)

Bronchoalveolar carcinoma: an adenocarcinoma subtype arising from the alveoli and adjacent small airways (probably from type II pneumocytes)  it presents as peripheral pulmonary opacities

it presents as peripheral pulmonary opacities

asbestos exposure, interstitial pulmonary fibrosis and radiotherapy are additional risks

asbestos exposure, interstitial pulmonary fibrosis and radiotherapy are additional risks

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

cough

cough  wheeze

wheeze  haemoptysis

haemoptysis

Cushing’s syndrome (ACTH)

Cushing’s syndrome (ACTH)  carcinoid syndrome

carcinoid syndrome  hypercalcaemia (PTH)

hypercalcaemia (PTH)

chest pain

chest pain  brachial plexus neuropathy or Horner’s syndrome (due to a Pancoast’s tumour)

brachial plexus neuropathy or Horner’s syndrome (due to a Pancoast’s tumour)  SVC obstruction

SVC obstruction  dysphagia

dysphagia

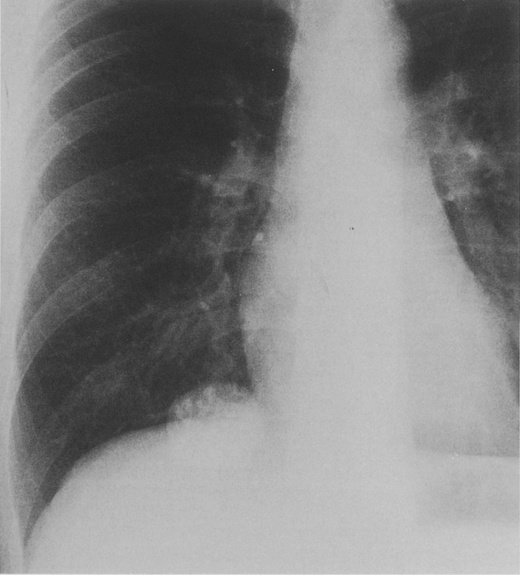

RADIOLOGICAL FEATURES

Peripheral tumours

lobulated masses can occur due to uneven growth rates

lobulated masses can occur due to uneven growth rates  there may be a ‘corona radiata’ due to numerous fine strands radiating into the lung

there may be a ‘corona radiata’ due to numerous fine strands radiating into the lung  a bronchocele or mucoid impaction can be seen distal to an obstructing carcinoma

a bronchocele or mucoid impaction can be seen distal to an obstructing carcinoma  collapse and consolidation is less commonly seen than with central tumours

collapse and consolidation is less commonly seen than with central tumours

Cavitation with irregular thick walls ± fluid levels (particularly squamous tumours)

Cavitation with irregular thick walls ± fluid levels (particularly squamous tumours)

Calcification is rare (6–10%) and may represent engulfed granulomatous disease

Calcification is rare (6–10%) and may represent engulfed granulomatous disease

Air bronchograms are rare but can be seen with bronchoalveolar carcinoma and adenocarcinoma

Air bronchograms are rare but can be seen with bronchoalveolar carcinoma and adenocarcinoma

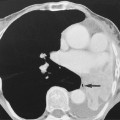

Chest wall invasion (T3)

contact with or a thickened pleura does not necessarily indicate invasion

contact with or a thickened pleura does not necessarily indicate invasion  a clear extrapleural fat plane is helpful but not definitive

a clear extrapleural fat plane is helpful but not definitive  reliable signs include clear-cut bone destruction or a large soft tissue mass

reliable signs include clear-cut bone destruction or a large soft tissue mass

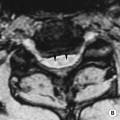

it is the optimal modality for demonstrating the extent of a superior sulcus tumour

it is the optimal modality for demonstrating the extent of a superior sulcus tumour

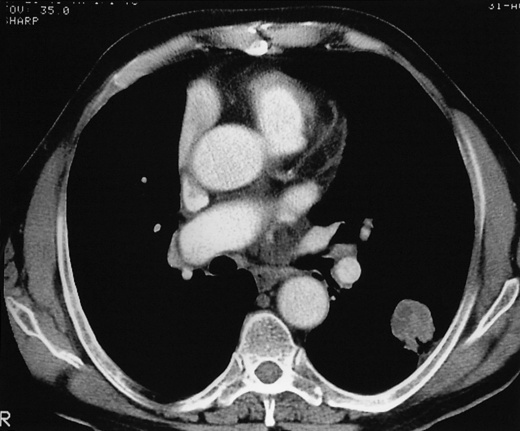

Mediastinal invasion (T4)

encasement of the mediastinal vessels, oesophagus, or proximal mainstem bronchi

encasement of the mediastinal vessels, oesophagus, or proximal mainstem bronchi  SVC obstruction

SVC obstruction  an elevated hemidiaphragm (indicating phrenic nerve involvement)

an elevated hemidiaphragm (indicating phrenic nerve involvement)

< 90° of circumferential contact with the aorta

< 90° of circumferential contact with the aorta  a visible mediastinal fat plane between the mass and any vital mediastinal structure

a visible mediastinal fat plane between the mass and any vital mediastinal structure

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

a positive result is 97% sensitive and 82% specific for malignancy

a positive result is 97% sensitive and 82% specific for malignancy it can also occur if the nodule is due to a carcinoid tumour or a slow-growing broncho-alveolar carcinoma

it can also occur if the nodule is due to a carcinoid tumour or a slow-growing broncho-alveolar carcinoma

a likelihood ratio < 1.0 typically indicates a benign lesion

a likelihood ratio < 1.0 typically indicates a benign lesion  a likelihood ratio > 1.0 typically indicates a malignant lesion

a likelihood ratio > 1.0 typically indicates a malignant lesion any peripheral collapsed lung will enhance more than a central tumour

any peripheral collapsed lung will enhance more than a central tumour  collateral air drift may prevent some post-obstructive changes

collateral air drift may prevent some post-obstructive changes

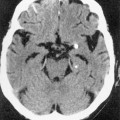

extensive hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy is typical of small cell tumours

extensive hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy is typical of small cell tumours haematogenous osteolytic bone metastases

haematogenous osteolytic bone metastases  hypertrophic osteoarthopathy

hypertrophic osteoarthopathy