Chapter 9 Recognizing Adult Heart Disease

Recognizing an Enlarged Cardiac Silhouette

The cardiac silhouette can appear enlarged for three main reasons:

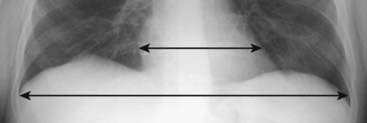

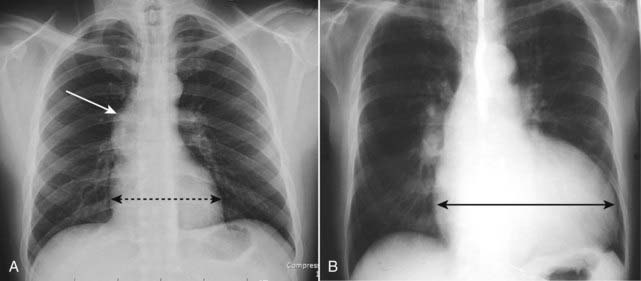

The cardiac silhouette can appear enlarged for three main reasons:![]() You can estimate the size of the cardiac silhouette on the frontal chest radiograph using the cardiothoracic ratio, which is a measurement of the widest transverse diameter of the heart compared to the widest internal diameter of the rib cage (from inside of rib to inside of rib at the level of the diaphragm) (Fig. 9-1).

You can estimate the size of the cardiac silhouette on the frontal chest radiograph using the cardiothoracic ratio, which is a measurement of the widest transverse diameter of the heart compared to the widest internal diameter of the rib cage (from inside of rib to inside of rib at the level of the diaphragm) (Fig. 9-1).

In most normal adults at full inspiration, the cardiothoracic ratio is less than 50%. That is, the size of the heart is usually less than half of the internal diameter of the thoracic rib cage.

In most normal adults at full inspiration, the cardiothoracic ratio is less than 50%. That is, the size of the heart is usually less than half of the internal diameter of the thoracic rib cage.Pericardial Effusion

Normally, there are 15-50 mL of fluid in the pericardial space between the parietal and visceral pericardial layers.

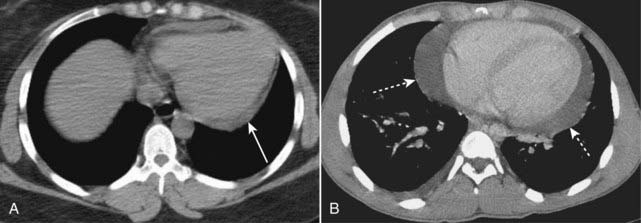

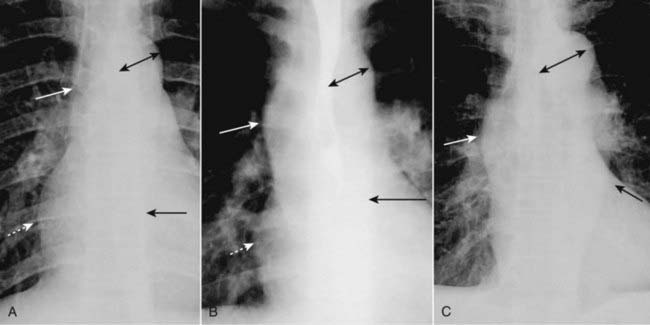

Normally, there are 15-50 mL of fluid in the pericardial space between the parietal and visceral pericardial layers. Abnormal accumulations of fluid begin in the dependent portions of the pericardial space, which, in the supine position, is posterior to the left ventricle (Fig. 9-2A).

Abnormal accumulations of fluid begin in the dependent portions of the pericardial space, which, in the supine position, is posterior to the left ventricle (Fig. 9-2A). As the pericardial effusion increases in size, it tends to accumulate more along the right heart border until it fills the pericardial space and encircles the heart (Fig. 9-2B).

As the pericardial effusion increases in size, it tends to accumulate more along the right heart border until it fills the pericardial space and encircles the heart (Fig. 9-2B). CT scans can demonstrate small pericardial effusions, although pericardial ultrasonography is usually the imaging study of first choice. Conventional radiographs are poor at defining a pericardial effusion.

CT scans can demonstrate small pericardial effusions, although pericardial ultrasonography is usually the imaging study of first choice. Conventional radiographs are poor at defining a pericardial effusion.Extracardiac Causes of Apparent Cardiac Enlargement

Sometimes, there is an extracardiac cause of apparent cardiac enlargement that may cause the cardiothoracic ratio to appear greater than 50%, while the heart itself may actually be normal in size.

Sometimes, there is an extracardiac cause of apparent cardiac enlargement that may cause the cardiothoracic ratio to appear greater than 50%, while the heart itself may actually be normal in size. The extracardiac causes of apparent cardiomegaly are outlined in Table 9-1. Magnification of the heart produced by projection, usually on a supine, portable chest examination, is the most common cause of apparent cardiomegaly.

The extracardiac causes of apparent cardiomegaly are outlined in Table 9-1. Magnification of the heart produced by projection, usually on a supine, portable chest examination, is the most common cause of apparent cardiomegaly.TABLE 9-1 EXTRACARDIAC CAUSES OF APPARENT CARDIOMEGALY

| Cause | Reason for Enlarged Appearance |

|---|---|

| AP portable supine chest—most common cause | Magnification due to AP projection |

| Suboptimal inspiration | In expiration, the diaphragm moves upward and compresses the heart, making the heart appear larger than it would in full inspiration If there are 8 or 9 posterior ribs visible on the frontal chest radiograph, then the inspiration is adequate (see Fig. 2-13) |

| Obesity, pregnancy, ascites | These conditions prevent an adequate inspiration |

| Pectus excavatum deformity, a congenital deformity of the lowermost section of the sternum, causes it to bow inward and compress the heart | The heart is compressed between the sternum and the spine |

| Rotation | Especially when it occurs to the patient’s left, rotation may make the heart appear larger |

| Pericardial effusion | Other imaging modalities (most commonly ultrasound) or electrocardiographic findings will help to identify pericardial fluid |

Effect of Projection on Perception of Heart Size

Because the heart resides anteriorly in the chest, on a posteroanterior (PA) chest radiograph (the standard frontal chest study in which the x-ray beam enters posteriorly and exits anteriorly where the imaging cassette is positioned), the heart appears truer to its actual size because it is nearer the imaging surface.

Because the heart resides anteriorly in the chest, on a posteroanterior (PA) chest radiograph (the standard frontal chest study in which the x-ray beam enters posteriorly and exits anteriorly where the imaging cassette is positioned), the heart appears truer to its actual size because it is nearer the imaging surface. On an anteroposterior (AP) chest radiograph (the usual bedside, portable chest radiograph in which the x-ray beam enters anteriorly and exits posteriorly where the cassette is positioned), the heart is slightly magnified because it is farther from the imaging surface.

On an anteroposterior (AP) chest radiograph (the usual bedside, portable chest radiograph in which the x-ray beam enters anteriorly and exits posteriorly where the cassette is positioned), the heart is slightly magnified because it is farther from the imaging surface.Identifying Cardiac Enlargement on an Anteroposterior Chest Radiograph

So is it possible to estimate the size of the heart on a portable chest radiograph? Glad you asked, because the answer is “yes.”

So is it possible to estimate the size of the heart on a portable chest radiograph? Glad you asked, because the answer is “yes.” If the heart is borderline enlarged on a portable AP radiograph, it is probably normal in size (Table 9-2).

If the heart is borderline enlarged on a portable AP radiograph, it is probably normal in size (Table 9-2). A good rule of thumb: If the heart appears enlarged on a well-inspired, portable chest radiograph, it probably is enlarged.

A good rule of thumb: If the heart appears enlarged on a well-inspired, portable chest radiograph, it probably is enlarged.TABLE 9-2 RECOGNIZING CARDIOMEGALY ON AN AP CHEST RADIOGRAPH

| Appearance of Heart on AP Study | Likely Heart Size |

|---|---|

| Borderline enlarged | Normal size |

| Significantly enlarged | Enlarged |

| Touching, or almost touching, the left lateral chest wall | Definitely enlarged |

Recognizing Cardiomegaly on the Lateral Chest Radiograph

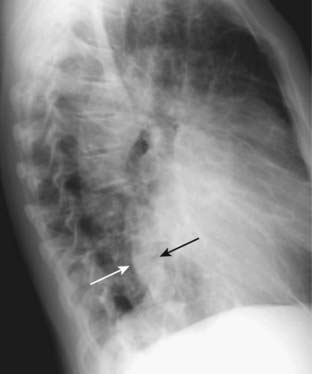

To evaluate for the presence of enlargement of the cardiac silhouette in the lateral projection, look at the space posterior to the heart and anterior to the spine at the level of the diaphragm.

To evaluate for the presence of enlargement of the cardiac silhouette in the lateral projection, look at the space posterior to the heart and anterior to the spine at the level of the diaphragm. In a normal person, the cardiac silhouette will usually not extend posteriorly and project over the spine (see Fig. 2-2).

In a normal person, the cardiac silhouette will usually not extend posteriorly and project over the spine (see Fig. 2-2). As the heart enlarges, whether that enlargement is due to cardiomegaly or pericardial effusion, the posterior border of the heart may extend to, or overlap, the anterior border of the thoracic spine. This can be useful as a confirmatory sign of cardiac enlargement first suspected on the frontal projection (Fig. 9-3).

As the heart enlarges, whether that enlargement is due to cardiomegaly or pericardial effusion, the posterior border of the heart may extend to, or overlap, the anterior border of the thoracic spine. This can be useful as a confirmatory sign of cardiac enlargement first suspected on the frontal projection (Fig. 9-3).Recognizing Cardiomegaly in Infants

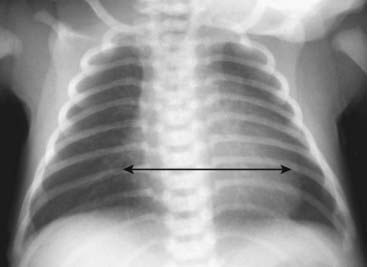

Although this chapter focuses primarily on adult cardiac disease, in newborns and infants it is important to remember that the heart will normally appear larger relative to the size of the thorax than it does in adults. Whereas a cardiothoracic ratio greater than 50% is considered abnormal in adults, the cardiothoracic ratio may reach up to 65% in infants and still be normal because newborns cannot take as deep an inspiration as adults can and the relative proportions in the size of their abdomen to chest are not the same as for adults (Fig. 9-4).

Although this chapter focuses primarily on adult cardiac disease, in newborns and infants it is important to remember that the heart will normally appear larger relative to the size of the thorax than it does in adults. Whereas a cardiothoracic ratio greater than 50% is considered abnormal in adults, the cardiothoracic ratio may reach up to 65% in infants and still be normal because newborns cannot take as deep an inspiration as adults can and the relative proportions in the size of their abdomen to chest are not the same as for adults (Fig. 9-4). Any assessment of cardiac enlargement in an infant should take into account other factors such as the appearance of the pulmonary vasculature and any associated clinical signs or symptoms (e.g., a murmur, tachycardia, or cyanosis).

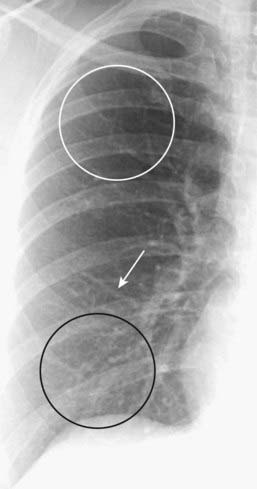

Any assessment of cardiac enlargement in an infant should take into account other factors such as the appearance of the pulmonary vasculature and any associated clinical signs or symptoms (e.g., a murmur, tachycardia, or cyanosis).![]() Also, in a child the thymus gland may overlap portions of the heart and sometimes mimic cardiomegaly. The normal thymus may be seen on conventional chest radiographs up to 3 years of age and sometimes may be seen as late as 8 years of age. The normal thymus gland has a somewhat lobulated appearance, especially where the ribs indent it (Fig. 9-5).

Also, in a child the thymus gland may overlap portions of the heart and sometimes mimic cardiomegaly. The normal thymus may be seen on conventional chest radiographs up to 3 years of age and sometimes may be seen as late as 8 years of age. The normal thymus gland has a somewhat lobulated appearance, especially where the ribs indent it (Fig. 9-5).

Normal Cardiac Contours

The normal cardiac contours comprise a series of bumps and indentations visible on the frontal chest radiograph. They are demonstrated in Figure 9-6.

The normal cardiac contours comprise a series of bumps and indentations visible on the frontal chest radiograph. They are demonstrated in Figure 9-6.![]() Key points about the cardiac contours:

Key points about the cardiac contours:

Normal Pulmonary Vasculature

The main pulmonary artery segment is usually concave or flat. In younger females it may normally be convex outward.

The main pulmonary artery segment is usually concave or flat. In younger females it may normally be convex outward. Normally, blood vessels branch and taper gradually from central (the hila) to peripheral (near the chest wall) (Fig. 9-8).

Normally, blood vessels branch and taper gradually from central (the hila) to peripheral (near the chest wall) (Fig. 9-8). Changes in pressure or flow can alter the normal dynamics of the pulmonary vasculature, some of which are described later in this chapter under “Recognizing Common Cardiac Disorders.”

Changes in pressure or flow can alter the normal dynamics of the pulmonary vasculature, some of which are described later in this chapter under “Recognizing Common Cardiac Disorders.”General Principles of Cardiac Imaging

As you interpret cardiac abnormalities, no matter what modality is being used, the following principles hold true:

As you interpret cardiac abnormalities, no matter what modality is being used, the following principles hold true:Recognizing Common Cardiac Diseases

Congestive Heart Failure

The incidence of congestive heart failure (CHF) has grown rapidly over the last two decades so that CHF is the most common diagnosis in hospitalized patients over the age of 65.

The incidence of congestive heart failure (CHF) has grown rapidly over the last two decades so that CHF is the most common diagnosis in hospitalized patients over the age of 65.Pulmonary Interstitial Edema

![]() Pulmonary interstitial edema has four key radiographic signs.

Pulmonary interstitial edema has four key radiographic signs.

Thickening of the interlobular septa: The Kerley B line

Thickening of the interlobular septa: The Kerley B line