Chapter 12 Recognizing Diseases of the Chest

A complete discussion of all of the abnormalities visible in the chest is beyond the scope of this text. We’ll begin here with mediastinal masses and work our way outward to the lungs.

A complete discussion of all of the abnormalities visible in the chest is beyond the scope of this text. We’ll begin here with mediastinal masses and work our way outward to the lungs.TABLE 12-1 CHEST ABNORMALITIES DISCUSSED ELSEWHERE IN THIS TEXT

| Topic | Appears in |

|---|---|

| Atelectasis | Chapter 5 |

| Pleural effusion | Chapter 6 |

| Pneumonia | Chapter 7 |

| Pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and pneumopericardium | Chapter 8 |

| Cardiac and thoracic aortic abnormalities | Chapter 9 |

| Chest trauma | Chapter 17 |

Mediastinal Masses

The mediastinum is an area whose lateral margins are defined by the medial borders of each lung, whose anterior margin is the sternum and anterior chest wall, and whose posterior margin is the spine, usually including the paravertebral gutters.

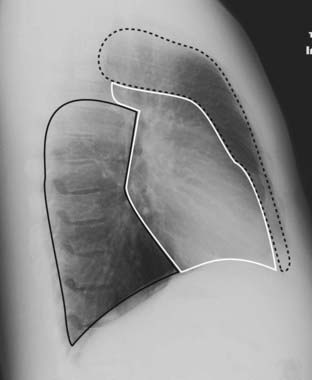

The mediastinum is an area whose lateral margins are defined by the medial borders of each lung, whose anterior margin is the sternum and anterior chest wall, and whose posterior margin is the spine, usually including the paravertebral gutters. The mediastinum can be arbitrarily subdivided into three compartments: the anterior, middle, and posterior compartments—and each contains its favorite set of diseases (Fig. 12-1).

The mediastinum can be arbitrarily subdivided into three compartments: the anterior, middle, and posterior compartments—and each contains its favorite set of diseases (Fig. 12-1). Differentiating a mediastinal from a parenchymal lung mass on frontal and lateral chest radiographs:

Differentiating a mediastinal from a parenchymal lung mass on frontal and lateral chest radiographs:• Mediastinal masses will originate in the mediastinum (makes sense, doesn’t it?), although large masses may be difficult to place.

• If a mass is surrounded by lung tissue in both the frontal and lateral projections, it lies within the lung; if a mass is surrounded by lung tissue in one but not both projections, it may be in either the lung or the mediastinum.

• In general (note that this is a generalization), the margin of a mediastinal mass is sharper than a mass originating in the lung.

Anterior Mediastinum

The anterior mediastinum is the compartment that extends from the back of the sternum to the anterior border of the heart and great vessels.

The anterior mediastinum is the compartment that extends from the back of the sternum to the anterior border of the heart and great vessels.TABLE 12-2 ANTERIOR MEDIASTINAL MASSES (“3 Ts and an L”)

| Mass | What to Look For |

|---|---|

| Thyroid goiter | The only anterior mediastinal mass that routinely deviates the trachea |

| Lymphoma (lymphadenopathy) | Lobulated, polycyclic mass, frequently asymmetrical, that may occur in any compartment of the mediastinum |

| Thymoma | Look for a well-marginated mass that may be associated with myasthenia gravis |

| Teratoma | Well-marginated mass that may contain fat and calcium on CT scans |

Thyroid Masses

In everyday practice, enlarged substernal thyroid masses are the most frequently encountered anterior mediastinal mass. The vast majority of these masses are multinodular goiters, and the mass is called a substernal goiter or substernal thyroid or substernal thyroid goiter.

In everyday practice, enlarged substernal thyroid masses are the most frequently encountered anterior mediastinal mass. The vast majority of these masses are multinodular goiters, and the mass is called a substernal goiter or substernal thyroid or substernal thyroid goiter. On occasion, the isthmus or lower pole of either lobe of the thyroid may enlarge but project downward into the upper thorax rather than anteriorly into the neck.

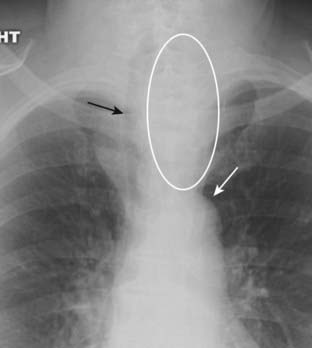

On occasion, the isthmus or lower pole of either lobe of the thyroid may enlarge but project downward into the upper thorax rather than anteriorly into the neck. Substernal goiters characteristically displace the trachea either to the left or right above the level of the aortic arch, a tendency the other anterior mediastinal masses do not typically demonstrate. Classically, substernal goiters do not extend below the top of the aortic arch (Fig. 12-2).

Substernal goiters characteristically displace the trachea either to the left or right above the level of the aortic arch, a tendency the other anterior mediastinal masses do not typically demonstrate. Classically, substernal goiters do not extend below the top of the aortic arch (Fig. 12-2). Radioisotope thyroid scans are the study of choice in confirming the diagnosis of a substernal thyroid because virtually all goiters will display some uptake of the radioactive tracer that can be imaged and recorded with a special camera.

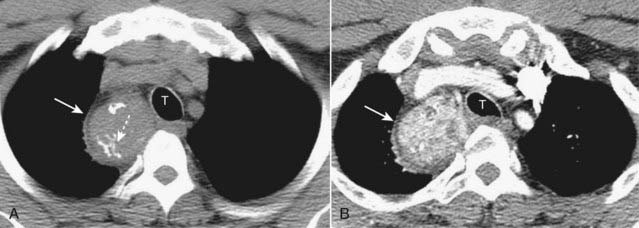

Radioisotope thyroid scans are the study of choice in confirming the diagnosis of a substernal thyroid because virtually all goiters will display some uptake of the radioactive tracer that can be imaged and recorded with a special camera. On CT scans, substernal thyroid masses are contiguous with the thyroid gland, frequently contain calcification, and avidly take up intravenous contrast but with a mottled, inhomogeneous appearance (Fig. 12-3).

On CT scans, substernal thyroid masses are contiguous with the thyroid gland, frequently contain calcification, and avidly take up intravenous contrast but with a mottled, inhomogeneous appearance (Fig. 12-3).Lymphoma

Lymphadenopathy, whether from lymphoma, metastatic carcinoma, sarcoid, or tuberculosis, is the most common cause of a mediastinal mass overall.

Lymphadenopathy, whether from lymphoma, metastatic carcinoma, sarcoid, or tuberculosis, is the most common cause of a mediastinal mass overall. Anterior mediastinal lymphadenopathy is most common in Hodgkin disease, especially the nodular sclerosing variety.

Anterior mediastinal lymphadenopathy is most common in Hodgkin disease, especially the nodular sclerosing variety. Hodgkin disease is a malignancy of the lymph nodes, more common in females, which most often presents with painless, enlarged lymph nodes in the neck.

Hodgkin disease is a malignancy of the lymph nodes, more common in females, which most often presents with painless, enlarged lymph nodes in the neck. Unlike teratomas and thymomas, which are presumed to expand outward from a single abnormal cell, lymphomatous masses are frequently composed of several contiguously enlarged lymph nodes. As such, lymphadenopathy frequently presents with a border that is lobulated or polycyclic in contour owing to the conglomeration of enlarged nodes that make up the mass.

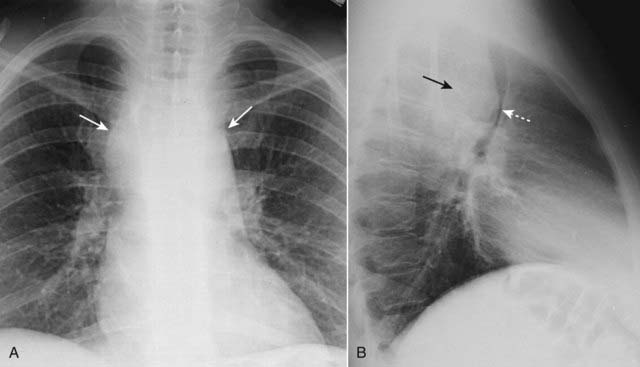

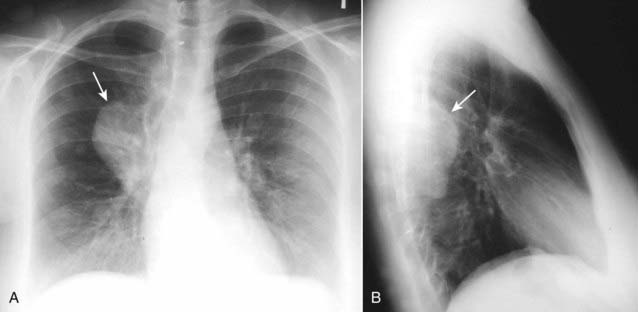

Unlike teratomas and thymomas, which are presumed to expand outward from a single abnormal cell, lymphomatous masses are frequently composed of several contiguously enlarged lymph nodes. As such, lymphadenopathy frequently presents with a border that is lobulated or polycyclic in contour owing to the conglomeration of enlarged nodes that make up the mass. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy in Hodgkin disease is usually bilateral and asymmetrical (Fig. 12-4). In addition, asymmetrical hilar adenopathy is associated with mediastinal adenopathy in many patients with Hodgkin disease.

Mediastinal lymphadenopathy in Hodgkin disease is usually bilateral and asymmetrical (Fig. 12-4). In addition, asymmetrical hilar adenopathy is associated with mediastinal adenopathy in many patients with Hodgkin disease. In general, mediastinal lymph nodes that exceed 1 cm measured along their short axis on CT scans of the chest are considered to be enlarged.

In general, mediastinal lymph nodes that exceed 1 cm measured along their short axis on CT scans of the chest are considered to be enlarged. Lymphoma will produce multiple, lobulated soft-tissue masses or one large soft-tissue mass from lymph node aggregation.

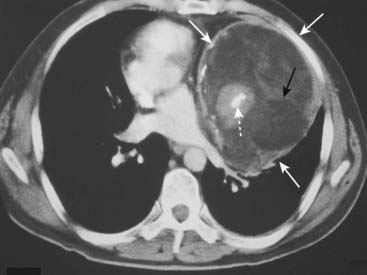

Lymphoma will produce multiple, lobulated soft-tissue masses or one large soft-tissue mass from lymph node aggregation. The mass is usually homogeneous in density on CT but may be heterogeneous when it achieves a sufficient size to undergo necrosis (areas of lower attenuation, i.e., blacker) or hemorrhage (areas of higher attenuation, i.e., whiter) (Fig. 12-5).

The mass is usually homogeneous in density on CT but may be heterogeneous when it achieves a sufficient size to undergo necrosis (areas of lower attenuation, i.e., blacker) or hemorrhage (areas of higher attenuation, i.e., whiter) (Fig. 12-5). Some findings of lymphoma may mimic those of sarcoid since both produce thoracic adenopathy. Table 12-3 helps to differentiate them.

Some findings of lymphoma may mimic those of sarcoid since both produce thoracic adenopathy. Table 12-3 helps to differentiate them.TABLE 12-3 SARCOIDOSIS VS. LYMPHOMA

| Sarcoid | Lymphoma |

|---|---|

| Bilateral hilar and right paratracheal adenopathy classic combination | More often mediastinal adenopathy, associated with asymmetrical hilar enlargement |

| Bronchopulmonary nodes more peripheral | Hilar nodes more central |

| Pleural effusion in about 5% | Pleural effusion more common—in 30% |

| Anterior mediastinal adenopathy is uncommon | Anterior mediastinal adenopathy is common |

Thymic Masses

Normal thymic tissue can be visible on CT throughout life, although the gland begins to involute after age 20.

Normal thymic tissue can be visible on CT throughout life, although the gland begins to involute after age 20. Thymomas are neoplasms of thymic epithelium and lymphocytes. They occur most often in middle-aged adults, generally at an older age than those with teratomas. Most thymomas are benign.

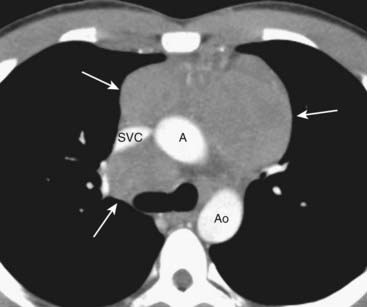

Thymomas are neoplasms of thymic epithelium and lymphocytes. They occur most often in middle-aged adults, generally at an older age than those with teratomas. Most thymomas are benign. On CT scans, thymomas classically present as a smooth or lobulated mass that arises near the junction of the heart and great vessels, which, like a teratoma, may contain calcification (Fig. 12-6).

On CT scans, thymomas classically present as a smooth or lobulated mass that arises near the junction of the heart and great vessels, which, like a teratoma, may contain calcification (Fig. 12-6). Other lesions that can produce enlargement of the thymus include thymic cysts, thymic hyperplasia, thymic lymphoma, carcinoma, or lipoma.

Other lesions that can produce enlargement of the thymus include thymic cysts, thymic hyperplasia, thymic lymphoma, carcinoma, or lipoma.Teratoma

Teratomas are germinal tumors that typically contain all three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm). Most teratomas are benign and occur earlier in life than thymomas. Usually asymptomatic and discovered serendipitously, about 30% of mediastinal teratomas are malignant and have a poor prognosis.

Teratomas are germinal tumors that typically contain all three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm). Most teratomas are benign and occur earlier in life than thymomas. Usually asymptomatic and discovered serendipitously, about 30% of mediastinal teratomas are malignant and have a poor prognosis. The most common variety of teratoma is cystic; it produces a well-marginated mass near the origin of the great vessels that characteristically contains fat, cartilage, and possibly bone on CT examination (Fig. 12-7).

The most common variety of teratoma is cystic; it produces a well-marginated mass near the origin of the great vessels that characteristically contains fat, cartilage, and possibly bone on CT examination (Fig. 12-7).Middle Mediastinum

The middle mediastinum is the compartment that extends from the anterior border of the heart and aorta to the posterior border of the heart and contains the heart, the origins of the great vessels, trachea, and main bronchi along with lymph nodes (see Fig. 12-1).

The middle mediastinum is the compartment that extends from the anterior border of the heart and aorta to the posterior border of the heart and contains the heart, the origins of the great vessels, trachea, and main bronchi along with lymph nodes (see Fig. 12-1). Lymphadenopathy produces the most common mass in this compartment. While Hodgkin disease is the most likely cause of mediastinal adenopathy, other malignancies and several benign diseases can produce such findings.

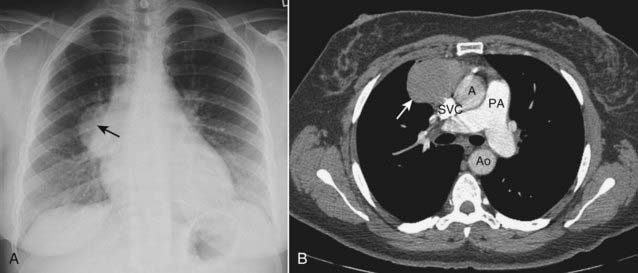

Lymphadenopathy produces the most common mass in this compartment. While Hodgkin disease is the most likely cause of mediastinal adenopathy, other malignancies and several benign diseases can produce such findings.• Other malignancies that produce mediastinal lymphadenopathy include small cell lung carcinoma and metastatic disease such as from primary breast carcinoma (Fig. 12-8).

Posterior Mediastinum

The posterior mediastinum is the compartment that extends from the posterior border of the heart to the anterior border of the vertebral column. For practical purposes, however, it is considered to extend to either side of the spine into the paravertebral gutters (see Fig. 12-1).

The posterior mediastinum is the compartment that extends from the posterior border of the heart to the anterior border of the vertebral column. For practical purposes, however, it is considered to extend to either side of the spine into the paravertebral gutters (see Fig. 12-1). It contains the descending aorta, esophagus, and lymph nodes and is the site of masses representing extramedullary hematopoiesis. Most importantly, it is the home of tumors of neural origin.

It contains the descending aorta, esophagus, and lymph nodes and is the site of masses representing extramedullary hematopoiesis. Most importantly, it is the home of tumors of neural origin.Neurogenic Tumors

Although neurogenic tumors produce the largest percentage of posterior mediastinal masses, none of these lesions is particularly common. Neurogenic tumors include such entities as neurofibroma, schwannoma (neurilemmoma), ganglioneuroma, and neuroblastoma.

Although neurogenic tumors produce the largest percentage of posterior mediastinal masses, none of these lesions is particularly common. Neurogenic tumors include such entities as neurofibroma, schwannoma (neurilemmoma), ganglioneuroma, and neuroblastoma. Nerve sheath tumors (Schwannoma or neurilemmoma) are the most common and are almost always benign. They usually affect persons 20-50 years of age. These slow-growing tumors may produce no symptoms until late in their course.

Nerve sheath tumors (Schwannoma or neurilemmoma) are the most common and are almost always benign. They usually affect persons 20-50 years of age. These slow-growing tumors may produce no symptoms until late in their course. Neoplasms that arise from nerve elements other than the sheath, such as ganglioneuromas and neuroblastoma, are usually malignant.

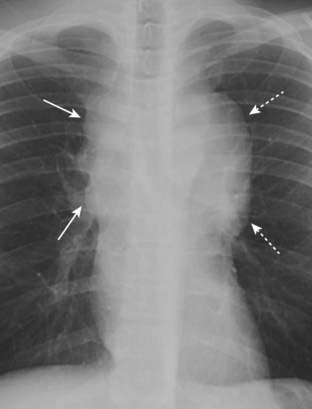

Neoplasms that arise from nerve elements other than the sheath, such as ganglioneuromas and neuroblastoma, are usually malignant. Neurogenic tumors will produce a soft tissue mass, usually sharply marginated, in the paravertebral gutter (Fig. 12-9). Both benign and malignant tumors may erode ribs (Fig. 12-10A). They may enlarge the neural foramina producing dumbbell–shaped lesions that arise from the spinal canal but project through the neural foramen into the mediastinum (Fig. 12-10B).

Neurogenic tumors will produce a soft tissue mass, usually sharply marginated, in the paravertebral gutter (Fig. 12-9). Both benign and malignant tumors may erode ribs (Fig. 12-10A). They may enlarge the neural foramina producing dumbbell–shaped lesions that arise from the spinal canal but project through the neural foramen into the mediastinum (Fig. 12-10B). Neurofibromas can occur as an isolated tumor arising from the Schwann cell of the nerve sheath or as part of a syndrome called neurofibromatosis. As part of the latter, they are a component of a neurocutaneous bone dysplasia that can cause numerous abnormalities, including subcutaneous nodules, erosion of adjacent bone (rib notching), scalloping of the posterior aspect of the vertebral bodies (Fig. 12-11), absence of the sphenoid wings, pseudarthroses, and sharp-angled kyphoscoliosis at the thoracolumbar junction.

Neurofibromas can occur as an isolated tumor arising from the Schwann cell of the nerve sheath or as part of a syndrome called neurofibromatosis. As part of the latter, they are a component of a neurocutaneous bone dysplasia that can cause numerous abnormalities, including subcutaneous nodules, erosion of adjacent bone (rib notching), scalloping of the posterior aspect of the vertebral bodies (Fig. 12-11), absence of the sphenoid wings, pseudarthroses, and sharp-angled kyphoscoliosis at the thoracolumbar junction.