Chapter 18 Recognizing Gastrointestinal, Hepatic, and Urinary Tract Abnormalities

In this chapter, you’ll learn how to recognize some of the most common abnormalities of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract from the esophagus to the rectum. We’ll also discuss selected hepatic abnormalities. Chapter 19 on ultrasound will describe some of the more common biliary and pelvic abnormalities.

In this chapter, you’ll learn how to recognize some of the most common abnormalities of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract from the esophagus to the rectum. We’ll also discuss selected hepatic abnormalities. Chapter 19 on ultrasound will describe some of the more common biliary and pelvic abnormalities. CT, ultrasound, and MRI have essentially replaced conventional radiography and, in some instances, barium studies for the evaluation of the GI tract and the visceral abdominal organs.

CT, ultrasound, and MRI have essentially replaced conventional radiography and, in some instances, barium studies for the evaluation of the GI tract and the visceral abdominal organs.Barium Studies of the Gastrointestinal Tract

During the performance of barium studies, fluoroscopic spot films and overhead films are usually obtained by the radiologist and radiologic technologist in several projections for whatever part of the GI tract is being studied, depending on the nature of the abnormality and the mobility of the patient.

During the performance of barium studies, fluoroscopic spot films and overhead films are usually obtained by the radiologist and radiologic technologist in several projections for whatever part of the GI tract is being studied, depending on the nature of the abnormality and the mobility of the patient. As you go through this chapter, you will probably want to refer to the two tables in this chapter, one on terminology used in describing studies of the GI tract (Table 18-1) and the other on basic principles in GI radiology (Table 18-2), both of which will prove helpful in understanding the terms and concepts used here.

As you go through this chapter, you will probably want to refer to the two tables in this chapter, one on terminology used in describing studies of the GI tract (Table 18-1) and the other on basic principles in GI radiology (Table 18-2), both of which will prove helpful in understanding the terms and concepts used here.| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Fluoroscopy | Utilization by the radiologist of special x-ray-producing equipment to observe in real time the dynamic movement of the bowel and to optimally position the patient so as to obtain diagnostic images frequently referred to as “spot films”; in this chapter, the term is used in reference to utilizing x-rays to image the GI tract. |

| Barium | Barium sulphate in suspension is an inert, radiopaque material prepared in liquid form to study the intraluminal anatomy of the GI tract. |

| Single contrast/double contrast/biphasic examination | A single-contrast (also called full-column) study usually refers to a GI imaging procedure in which only barium is used as the contrast agent; double contrast (sometimes called air contrast) usually refers to a study of the GI tract using both thicker barium and air; a biphasic examination is used to study the upper gastrointestinal tract and utilizes an initial double contrast study followed by a single contrast agent to optimize the study. |

| Filling defect | A lesion, usually of soft tissue density, that protrudes into the lumen and displaces the intraluminal contrast (e.g., a polyp is a filling defect). |

| Ulcer | Refers to a persistent collection of contrast that projects outward from the contrast-filled lumen and originates either through a break in the mucosal lining (as in gastric ulcer) or in a GI mass (as in an ulcerating malignancy). |

| Diverticulum | Refers to a persistent collection of contrast that projects outward from the contrast-filled lumen of the GI tract like an ulcer; unlike an ulcer, the mucosa of a diverticulum is intact; false diverticula represent outpouchings of mucosa and submucosa through the muscularis. |

| Spot films and overhead films | Spot films usually refer to static images obtained by the radiologist who utilizes fluoroscopy to position the patient for the optimum image; overhead films is a term which refers to additional images obtained by the radiologic technologist to complement fluoroscopic spot films using an x-ray tube mounted on the ceiling of the radiographic room (thus, the term overhead). |

| Intraluminal, intramural, extrinsic | Intraluminal (sometimes shortened to luminal) lesions are generally those that arise from the mucosa, like polyps and carcinomas; intramural (sometimes shortened to mural) lesions are those that arise from the wall, in this chapter from the GI tract, such as leiomyomas and lipomas; extrinsic lesions arise outside of the GI tract, e.g., serosal metastases or endometriosis implants. |

| En face and in profile | When you look at a lesion directly “head-on,” you are seeing it en face; a lesion seen tangentially (from the side) is seen in profile; except for those that are perfect spheres, lesions will have a different shape when viewed en face and in profile. |

TABLE 18-2 COMMON PRINCIPLES FOR ALL BARIUM STUDIES

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Fully distended vs. collapsed | Only loops that are fully distended by contrast can be accurately evaluated no matter what part of the GI tract is being studied; evaluating certain criteria (such as wall thickness) using collapsed loops may introduce errors of diagnosis. |

| Change and distensibility | Over time (usually measured in seconds), the walls of all of the GI luminal structures, from esophagus to rectum, change in contour, distending and ballooning outward with increasing volumes of barium and air. Change and distensibility are normal. |

| Rigid, stiff, fixed, nondistensible | If the bowel wall is infiltrated by tumor, blood, edema, or fibrous tissue, for example, the bowel may lose its ability to change and distend; this lack of distensibility is variously called rigidity, stiffening, fixed, nondistensible. This is abnormal. |

| Irregularity | Except for the normal marginal indentations caused by the folds in the stomach, small bowel, and colon, the walls of the entire GI tract appear relatively smooth and regular; diseases can produce ulceration, infiltration, and nodularity with resultant irregularity of the wall. |

| Persistence | Almost without exception, an apparent abnormality must be seen on more than one image to be considered a pathologic finding; transient changes in the GI tract caused by peristalsis, ingested food, the presence of stool, or incompletely distended loops of bowel will disappear over time, but true abnormalities will remain constant and persistent. |

Esophagus

Single- and double-contrast examinations of the esophagus are performed with the patient drinking liquid barium either by itself (single contrast) or accompanied by a gas-producing agent that provides the “air” in a double-contrast examination. Since both the single- and double-contrast techniques have their own strengths, many esophagrams are routinely performed using both techniques, called a biphasic examination.

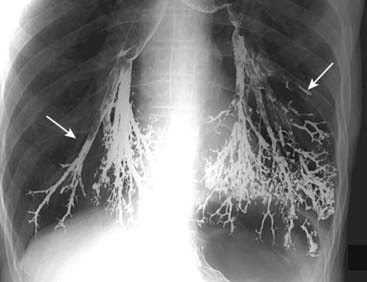

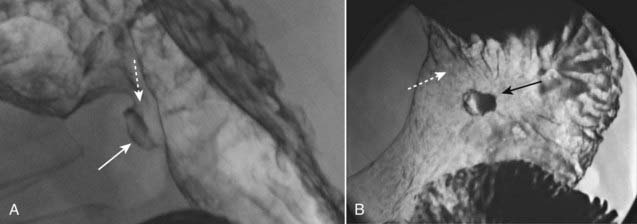

Single- and double-contrast examinations of the esophagus are performed with the patient drinking liquid barium either by itself (single contrast) or accompanied by a gas-producing agent that provides the “air” in a double-contrast examination. Since both the single- and double-contrast techniques have their own strengths, many esophagrams are routinely performed using both techniques, called a biphasic examination. Video esophagography (video swallowing function) is a study of the swallowing mechanism, usually performed with fluoroscopy and frequently captured dynamically—digitally, on videotape, or on film. This is the study of choice for diagnosing and documenting aspiration, in which ingested substances pass into the trachea below the level of the vocal cords (Fig. 18-1).

Video esophagography (video swallowing function) is a study of the swallowing mechanism, usually performed with fluoroscopy and frequently captured dynamically—digitally, on videotape, or on film. This is the study of choice for diagnosing and documenting aspiration, in which ingested substances pass into the trachea below the level of the vocal cords (Fig. 18-1). Fluoroscopic observation of the esophagus can also reveal abnormalities in esophageal motility. For example, tertiary waves are a common but nonspecific abnormality of esophageal motility, representing disordered and nonpropulsive contractions of the esophagus. They can be observed fluoroscopically and captured on spot images (Fig. 18-2).

Fluoroscopic observation of the esophagus can also reveal abnormalities in esophageal motility. For example, tertiary waves are a common but nonspecific abnormality of esophageal motility, representing disordered and nonpropulsive contractions of the esophagus. They can be observed fluoroscopically and captured on spot images (Fig. 18-2).Esophageal Diverticula

Diverticula of the GI tract are usually produced when the mucosal and submucosal layers herniate through a defect in the muscular layer of the bowel wall. Wherever they occur in the GI tract, diverticula produce an outpouching that projects beyond the borders of the lumen.

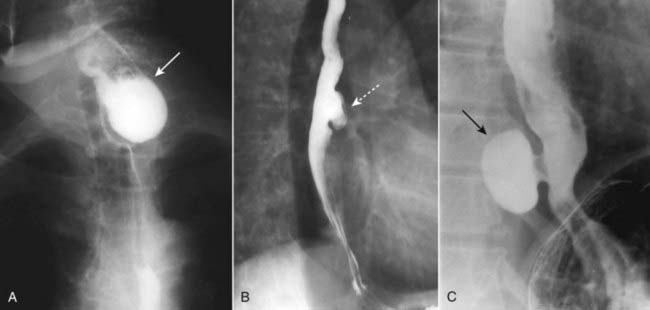

Diverticula of the GI tract are usually produced when the mucosal and submucosal layers herniate through a defect in the muscular layer of the bowel wall. Wherever they occur in the GI tract, diverticula produce an outpouching that projects beyond the borders of the lumen.![]() Esophageal diverticula occur in three locations: the neck, around the carina, and just above the diaphragm. In the neck, the diverticulum is posteriorly located and is called a Zenker diverticulum. Diverticula at the level of the carina may be due to extrinsic inflammatory disease like tuberculosis (traction diverticula); diverticula just above the esophagogastric junction are called epiphrenic diverticula (Fig. 18-3).

Esophageal diverticula occur in three locations: the neck, around the carina, and just above the diaphragm. In the neck, the diverticulum is posteriorly located and is called a Zenker diverticulum. Diverticula at the level of the carina may be due to extrinsic inflammatory disease like tuberculosis (traction diverticula); diverticula just above the esophagogastric junction are called epiphrenic diverticula (Fig. 18-3).

Esophageal Carcinoma

Esophageal carcinoma continues to have a very poor prognosis as more than 50% of patients will have metastases upon initial presentation. The lack of an esophageal serosa and a rich supply of lymphatics aid in the extension and dissemination of esophageal carcinoma. A combination of long-term alcohol and tobacco use are associated with a higher risk of esophageal carcinoma.

Esophageal carcinoma continues to have a very poor prognosis as more than 50% of patients will have metastases upon initial presentation. The lack of an esophageal serosa and a rich supply of lymphatics aid in the extension and dissemination of esophageal carcinoma. A combination of long-term alcohol and tobacco use are associated with a higher risk of esophageal carcinoma. Esophageal malignancies are either squamous cell carcinomas or adenocarcinomas, the latter of which are increasing in prevalence. Adenocarcinomas arise in esophageal epithelium that has undergone metaplasia from squamous to columnar epithelium (Barrett esophagus), a process in which gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) plays a major role.

Esophageal malignancies are either squamous cell carcinomas or adenocarcinomas, the latter of which are increasing in prevalence. Adenocarcinomas arise in esophageal epithelium that has undergone metaplasia from squamous to columnar epithelium (Barrett esophagus), a process in which gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) plays a major role. Barium esophagrams are frequently the initial study in patients with symptoms, like dysphagia, that suggest this diagnosis.

Barium esophagrams are frequently the initial study in patients with symptoms, like dysphagia, that suggest this diagnosis. Esophageal carcinomas may appear in one or more of several forms, including an annular-constricting lesion, polypoid mass, a superficial, infiltrating lesion or ulceration, and irregularity of the wall. Most often, they present as a mixture of several of these patterns (Fig. 18-4).

Esophageal carcinomas may appear in one or more of several forms, including an annular-constricting lesion, polypoid mass, a superficial, infiltrating lesion or ulceration, and irregularity of the wall. Most often, they present as a mixture of several of these patterns (Fig. 18-4).Hiatal Hernia and Gastroesophageal Reflux (GERD)

Hiatal hernias are divided into the sliding type (almost all) in which the esophagogastric (EG) junction lies above the diaphragm or the paraesophageal type (1%) in which a portion of the stomach herniates through the esophageal hiatus but the EG junction remains below the diaphragm. In general, hiatal hernias increase in incidence with age.

Hiatal hernias are divided into the sliding type (almost all) in which the esophagogastric (EG) junction lies above the diaphragm or the paraesophageal type (1%) in which a portion of the stomach herniates through the esophageal hiatus but the EG junction remains below the diaphragm. In general, hiatal hernias increase in incidence with age. Most hiatal hernias are asymptomatic, but there is an association between the presence of some hiatal hernias and clinically significant gastroesophageal reflux.

Most hiatal hernias are asymptomatic, but there is an association between the presence of some hiatal hernias and clinically significant gastroesophageal reflux. Gastroesophageal reflux may be evident during fluoroscopy when barium is seen to move from the stomach retrograde into the esophagus, but reflux is intermittent so that it may not occur during the course of the examination. The absence of reflux during the study does not exclude reflux, and demonstration of reflux does not necessarily indicate the patient has the complications of GERD, i.e., esophagitis, stricture, and Barrett esophagus.

Gastroesophageal reflux may be evident during fluoroscopy when barium is seen to move from the stomach retrograde into the esophagus, but reflux is intermittent so that it may not occur during the course of the examination. The absence of reflux during the study does not exclude reflux, and demonstration of reflux does not necessarily indicate the patient has the complications of GERD, i.e., esophagitis, stricture, and Barrett esophagus.Stomach and Duodenum

Today, the lumen of the stomach is most often studied by upper endoscopy; the wall thickness and structures outside of the stomach are studied by CT examination of the abdomen with oral contrast. Nevertheless, biphasic upper gastrointestinal (UGI) examinations, which include a study of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, remain a sensitive, cost-effective, readily available, and noninvasive examination.

Today, the lumen of the stomach is most often studied by upper endoscopy; the wall thickness and structures outside of the stomach are studied by CT examination of the abdomen with oral contrast. Nevertheless, biphasic upper gastrointestinal (UGI) examinations, which include a study of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, remain a sensitive, cost-effective, readily available, and noninvasive examination.Gastric Ulcers

In the United States, the incidence of gastric ulcer disease has been declining. In adults, infection with Helicobacter pylori accounts for almost three out of four cases of gastric ulcer disease. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents account for most of the rest.

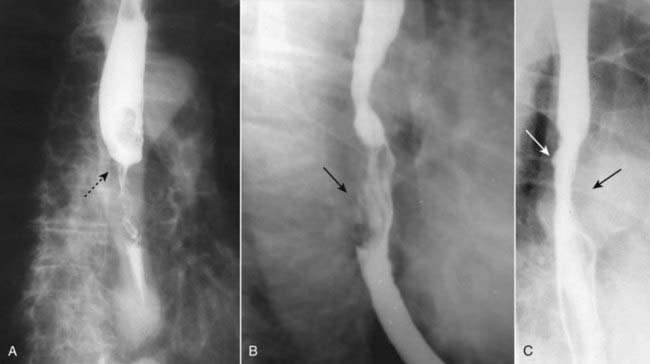

In the United States, the incidence of gastric ulcer disease has been declining. In adults, infection with Helicobacter pylori accounts for almost three out of four cases of gastric ulcer disease. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents account for most of the rest.![]() Most ulcers occur on the lesser curvature or posterior wall in the region of the body or antrum. About 95% of all gastric ulcers are benign. The other 5% will represent ulcerations in gastric malignancies (Fig. 18-6).

Most ulcers occur on the lesser curvature or posterior wall in the region of the body or antrum. About 95% of all gastric ulcers are benign. The other 5% will represent ulcerations in gastric malignancies (Fig. 18-6).

Gastric Carcinoma

There has been a dramatic decline in the incidence of gastric carcinomas in the United States. The mortality, however, remains quite high as they are frequently not diagnosed until after they have spread. Most gastric carcinomas (actually, they are adenocarcinomas) occur in the distal third of the stomach along the lesser curvature.

There has been a dramatic decline in the incidence of gastric carcinomas in the United States. The mortality, however, remains quite high as they are frequently not diagnosed until after they have spread. Most gastric carcinomas (actually, they are adenocarcinomas) occur in the distal third of the stomach along the lesser curvature. Double-contrast UGI images and CT scans of the abdomen can demonstrate gastric carcinomas. CT is utilized for staging the extent of the tumor and degree of spread.

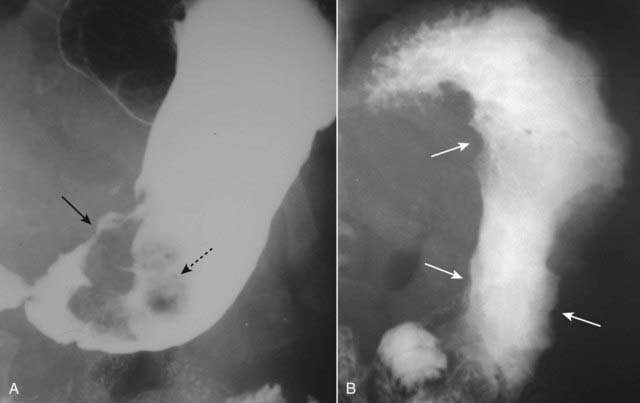

Double-contrast UGI images and CT scans of the abdomen can demonstrate gastric carcinomas. CT is utilized for staging the extent of the tumor and degree of spread. Gastric carcinomas may be polypoid, infiltrating (i.e., linitis plastica), or ulcerative in form (Fig. 18-7).

Gastric carcinomas may be polypoid, infiltrating (i.e., linitis plastica), or ulcerative in form (Fig. 18-7). There are other mass lesions that may resemble gastric carcinoma, including leiomyomas, a benign, wall lesion that characteristically ulcerates, and lymphoma, which may produce diffusely thickened folds or multiple masses in the stomach.

There are other mass lesions that may resemble gastric carcinoma, including leiomyomas, a benign, wall lesion that characteristically ulcerates, and lymphoma, which may produce diffusely thickened folds or multiple masses in the stomach.Duodenal Ulcer

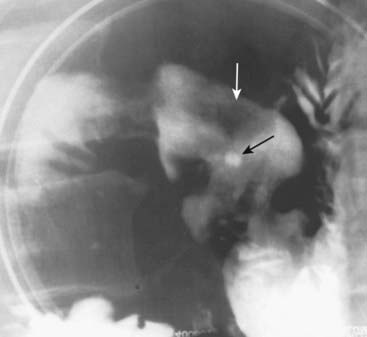

Double-contrast UGI series have a sensitivity that exceeds 90% in detecting duodenal ulcers (Fig. 18-8).

Double-contrast UGI series have a sensitivity that exceeds 90% in detecting duodenal ulcers (Fig. 18-8). Complications of duodenal ulcers, best demonstrated by CT, include obstruction, perforation (into the peritoneal cavity), penetration (such as into the pancreas), or hemorrhage (Fig. 18-9).

Complications of duodenal ulcers, best demonstrated by CT, include obstruction, perforation (into the peritoneal cavity), penetration (such as into the pancreas), or hemorrhage (Fig. 18-9).Small and Large Bowel

General Considerations

Opacification and distension of the bowel lumen is necessary for proper evaluation of the bowel no matter what imaging modality is used.

Opacification and distension of the bowel lumen is necessary for proper evaluation of the bowel no matter what imaging modality is used. Therefore, orally administered contrast, frequently given in temporally divided doses to allow earlier contrast to reach the colon while later contrast opacifies the stomach, is routinely utilized for most abdominal CT scans except those performed for trauma, the stone search study, and studies specifically directed towards evaluating vascular structures like the aorta.

Therefore, orally administered contrast, frequently given in temporally divided doses to allow earlier contrast to reach the colon while later contrast opacifies the stomach, is routinely utilized for most abdominal CT scans except those performed for trauma, the stone search study, and studies specifically directed towards evaluating vascular structures like the aorta. Thickening of the bowel wall. The normal small bowel lumen does not exceed about 2.5 cm in diameter, and the wall is usually no thicker than 3 mm. The colonic wall does not exceed 3 mm with the lumen distended.

Thickening of the bowel wall. The normal small bowel lumen does not exceed about 2.5 cm in diameter, and the wall is usually no thicker than 3 mm. The colonic wall does not exceed 3 mm with the lumen distended. Submucosal edema or hemorrhage. Submucosal infiltration produces varying degrees of thumbprinting, nodular indentations into the bowel lumen representing focal areas of submucosal infiltration by edema, hemorrhage, inflammatory cells, tumor (lymphoma), or amyloid.

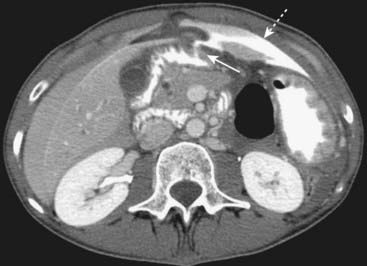

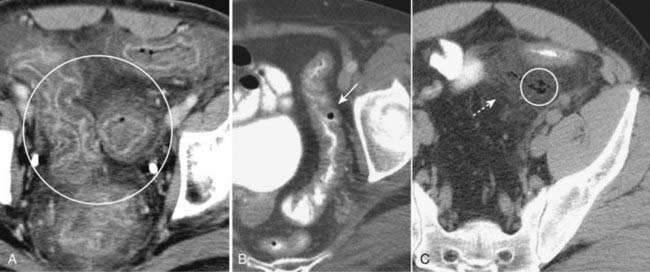

Submucosal edema or hemorrhage. Submucosal infiltration produces varying degrees of thumbprinting, nodular indentations into the bowel lumen representing focal areas of submucosal infiltration by edema, hemorrhage, inflammatory cells, tumor (lymphoma), or amyloid. Hazy or strandlike infiltration of the surrounding fat. Extension of inflammatory reaction outside of the bowel into the adjacent fat is a sentinel finding that heralds associated disease (Fig. 18-10).

Hazy or strandlike infiltration of the surrounding fat. Extension of inflammatory reaction outside of the bowel into the adjacent fat is a sentinel finding that heralds associated disease (Fig. 18-10). Extraluminal contrast or extraluminal air. Indicates the presence of a bowel perforation (Fig. 18-11).

Extraluminal contrast or extraluminal air. Indicates the presence of a bowel perforation (Fig. 18-11).Small Bowel: Crohn Disease

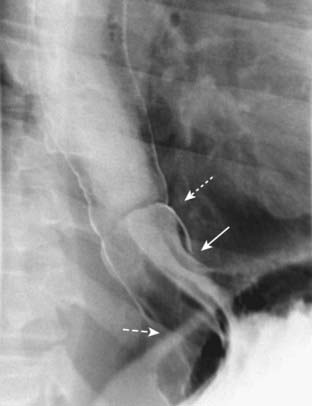

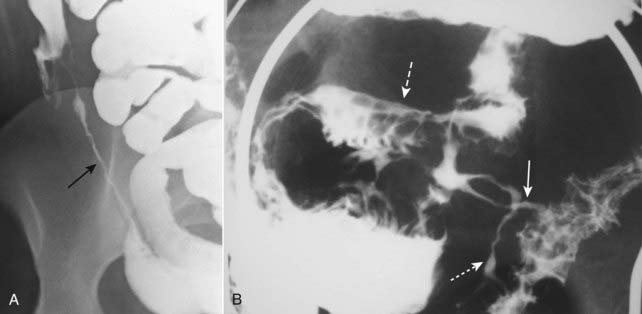

Crohn disease is a chronic, relapsing, granulomatous inflammation of the small bowel and colon resulting in ulceration, obstruction and fistula formation. Crohn disease typically involves the ileum and right colon, presents with skip areas (abnormal bowel interposed between normal bowel), is prone to fistula formation, and has a propensity for recurring following surgical resection and reanastamosis in whatever loop of bowel becomes the new terminal ileum.

Crohn disease is a chronic, relapsing, granulomatous inflammation of the small bowel and colon resulting in ulceration, obstruction and fistula formation. Crohn disease typically involves the ileum and right colon, presents with skip areas (abnormal bowel interposed between normal bowel), is prone to fistula formation, and has a propensity for recurring following surgical resection and reanastamosis in whatever loop of bowel becomes the new terminal ileum. Crohn disease may be imaged either with a barium small bowel follow-through (series) or CT of the abdomen and pelvis.

Crohn disease may be imaged either with a barium small bowel follow-through (series) or CT of the abdomen and pelvis.![]() Imaging findings in Crohn disease include narrowing, irregularity, and ulceration of the terminal ileum frequently with proximal small bowel dilatation; separation of the loops of bowel due to fatty infiltration of the mesentery surrounding the ileum, making the affected loop(s) stand apart from the surrounding loops of small bowel (proud loop); the string sign—narrowing of the terminal ileum into a near slitlike opening by spasm and fibrosis; and fistulae—especially between the ileum and colon but also to the skin, vagina, and urinary bladder (Fig. 18-12).

Imaging findings in Crohn disease include narrowing, irregularity, and ulceration of the terminal ileum frequently with proximal small bowel dilatation; separation of the loops of bowel due to fatty infiltration of the mesentery surrounding the ileum, making the affected loop(s) stand apart from the surrounding loops of small bowel (proud loop); the string sign—narrowing of the terminal ileum into a near slitlike opening by spasm and fibrosis; and fistulae—especially between the ileum and colon but also to the skin, vagina, and urinary bladder (Fig. 18-12).