Chapter 23 Recognizing Joint Disease

An Approach to Arthritis

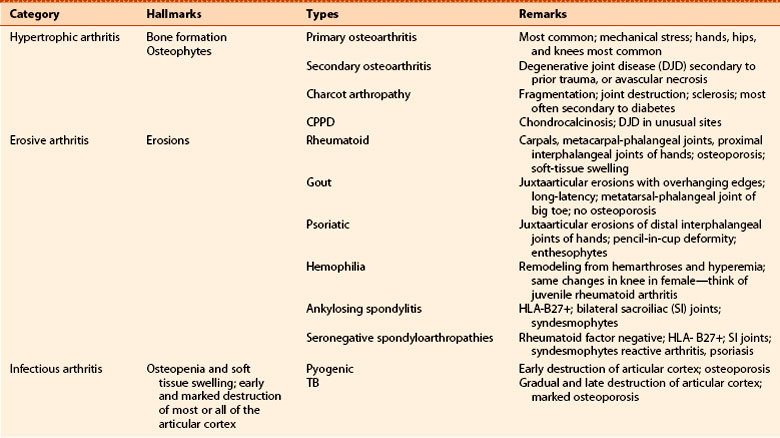

Imaging studies play a key role in the diagnosis and management of arthritis and are the method by which many arthritides are first diagnosed. Other arthritides are initially diagnosed on clinical and laboratory grounds and imaging is used to document the severity, extent, and course of the disease (Table 23-1).

Imaging studies play a key role in the diagnosis and management of arthritis and are the method by which many arthritides are first diagnosed. Other arthritides are initially diagnosed on clinical and laboratory grounds and imaging is used to document the severity, extent, and course of the disease (Table 23-1). Conventional radiographs demonstrate osseous abnormalities but provide only indirect and usually delayed evidence of abnormalities involving the soft tissues, such as the synovial lining of the joint, the articular cartilage, muscles, ligaments, and tendons surrounding the joint. MRI is used to demonstrate those soft tissue abnormalities.

Conventional radiographs demonstrate osseous abnormalities but provide only indirect and usually delayed evidence of abnormalities involving the soft tissues, such as the synovial lining of the joint, the articular cartilage, muscles, ligaments, and tendons surrounding the joint. MRI is used to demonstrate those soft tissue abnormalities.TABLE 23-1 ARTHRITIS: WHO MAKES THE DIAGNOSIS?

| Usually Diagnosed Clinically | Frequently Diagnosed Radiologically |

|---|---|

| Septic (pyogenic) arthritis | Osteoarthritis |

| Psoriatic arthritis | Early rheumatoid arthritis |

| Gout | Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | |

| Hemophilia | Septic (TB) |

| Charcot (neuropathic) joint—late |

Anatomy of A Joint

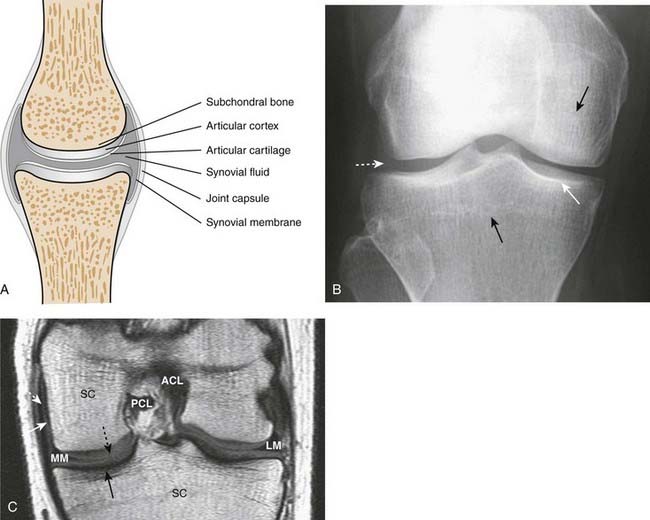

Figure 23-1 contains a diagram of a typical synovial joint and compares the structures visualized on conventional radiographs and MRI.

Figure 23-1 contains a diagram of a typical synovial joint and compares the structures visualized on conventional radiographs and MRI. The articular cortex is the thin, white line as seen on conventional radiographs that lies within the joint capsule and is usually capped by hyaline cartilage, called the articular cartilage. The bone immediately beneath the articular cortex is called subchondral bone.

The articular cortex is the thin, white line as seen on conventional radiographs that lies within the joint capsule and is usually capped by hyaline cartilage, called the articular cartilage. The bone immediately beneath the articular cortex is called subchondral bone. Lining the joint capsule is the synovial membrane containing synovial fluid. The synovial membrane is frequently the earliest structure involved by an arthritis.

Lining the joint capsule is the synovial membrane containing synovial fluid. The synovial membrane is frequently the earliest structure involved by an arthritis. Conventional radiographs will demonstrate abnormalities of the articular cortex and the subchondral bone and will provide late, indirect evidence of the integrity of the articular cartilage.

Conventional radiographs will demonstrate abnormalities of the articular cortex and the subchondral bone and will provide late, indirect evidence of the integrity of the articular cartilage. On conventional radiographs, the synovial membrane, synovial fluid, and the articular cartilage are usually not directly visible. All, however, are visible using MRI.

On conventional radiographs, the synovial membrane, synovial fluid, and the articular cartilage are usually not directly visible. All, however, are visible using MRI. While MRI is more sensitive in directly visualizing the soft tissues in and around a joint, conventional radiographs remain the study of first choice in evaluating for the presence of an arthritis.

While MRI is more sensitive in directly visualizing the soft tissues in and around a joint, conventional radiographs remain the study of first choice in evaluating for the presence of an arthritis.Classification of Arthritis

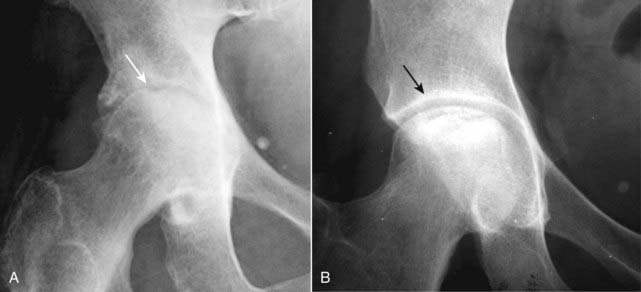

First, let’s define what an arthritis is and then we’ll outline a classification of arthritides. An arthritis is a disease that affects a joint and usually the bones on either side of the joint, almost always accompanied by joint space narrowing (Fig. 23-2).

First, let’s define what an arthritis is and then we’ll outline a classification of arthritides. An arthritis is a disease that affects a joint and usually the bones on either side of the joint, almost always accompanied by joint space narrowing (Fig. 23-2). We will divide arthritides into three main categories: (Table 23-2)

We will divide arthritides into three main categories: (Table 23-2)• Hypertrophic arthritis is characterized, in general, by bone formation at the site of the involved joint(s). The bone formation may occur within the confines of the parent bone (subchondral sclerosis) or protrude from the parent bone (osteophyte) (Fig. 23-3A).

• Erosive arthritis indicates underlying inflammation and is characterized by tiny, marginal, irregularly shaped lytic lesions in or around the joint surfaces called erosions (Fig. 23-3B).

Within each of these three main categories, we’ll look at a few of the more common types of arthritis that also have characteristic imaging findings.

Within each of these three main categories, we’ll look at a few of the more common types of arthritis that also have characteristic imaging findings.Hypertrophic Arthritis

Hypertrophic arthritis is characterized by bone formation, either within the confines of preexisting bone (subchondral sclerosis) or by bony protrusions extending from the normal bone (osteophytes).

Hypertrophic arthritis is characterized by bone formation, either within the confines of preexisting bone (subchondral sclerosis) or by bony protrusions extending from the normal bone (osteophytes). Hypertrophic arthritides include:

Hypertrophic arthritides include:• Osteoarthritis (degenerative arthritis, degenerative joint disease), which is further divided into:

Primary Osteoarthritis (Also Known as Primary Degenerative Arthritis, Degenerative Joint Disease)

This is the most common form of arthritis, estimated to affect over 20 million Americans. It results from intrinsic degeneration of the articular cartilage, mostly from the mechanical stress of excessive wear and tear in weight-bearing joints.

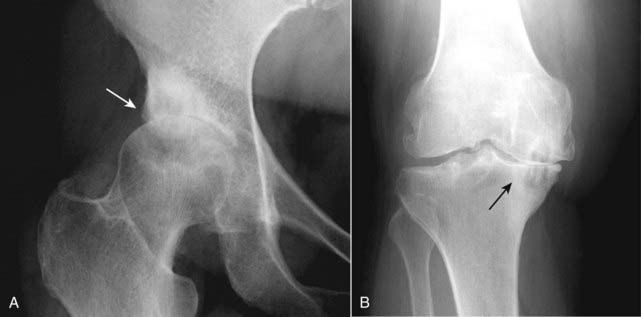

This is the most common form of arthritis, estimated to affect over 20 million Americans. It results from intrinsic degeneration of the articular cartilage, mostly from the mechanical stress of excessive wear and tear in weight-bearing joints. Marginal osteophyte formation. A hallmark of hypertrophic arthritis, osseous transformation of cartilaginous excrescences and metaplasia of synovial lining cells lead to the production of these bony protrusions at or near the joint (Fig. 23-4).

Marginal osteophyte formation. A hallmark of hypertrophic arthritis, osseous transformation of cartilaginous excrescences and metaplasia of synovial lining cells lead to the production of these bony protrusions at or near the joint (Fig. 23-4). Subchondral sclerosis. This is a reaction of the bone to the mechanical stress to which it is subjected when its protective cartilage has been destroyed.

Subchondral sclerosis. This is a reaction of the bone to the mechanical stress to which it is subjected when its protective cartilage has been destroyed. Subchondral cysts. As a result of chronic impaction, necrosis of bone and imposition of synovial fluid into the subchondral bone, cysts of varying sizes form in the subchondral bone.

Subchondral cysts. As a result of chronic impaction, necrosis of bone and imposition of synovial fluid into the subchondral bone, cysts of varying sizes form in the subchondral bone. What joints are involved?

What joints are involved?• In osteoarthritis, destruction of the cartilaginous buffer between the apposing bones of a joint leads to narrowing of the joint space most often on the weight-bearing side of the joint: hip (superior and lateral) and knee (medial) (Fig. 23-5).

• In most patients with osteoarthritis of the interphalangeal joints of the hands, the first carpometacarpal joint (base of thumb) is also affected (Fig. 23-6). It is also common for osteoarthritis to affect the distal interphalangeal joints, especially in older females.

Secondary Osteoarthritis (Secondary Degenerative Arthritis)

Secondary osteoarthritis is a form of degenerative arthritis of synovial joints that occurs because of an underlying, predisposing condition, most frequently trauma, that damages or leads to damage of the articular cartilage.

Secondary osteoarthritis is a form of degenerative arthritis of synovial joints that occurs because of an underlying, predisposing condition, most frequently trauma, that damages or leads to damage of the articular cartilage. The radiographic findings of secondary osteoarthritis are the same as those for the primary form with several special clues to help suggest secondary osteoarthritis:

The radiographic findings of secondary osteoarthritis are the same as those for the primary form with several special clues to help suggest secondary osteoarthritis:• It occurs at an atypical age for primary osteoarthritis (e.g., a 20-year-old with osteoarthritis) (Box 23-1).

• It has an atypical appearance for primary osteoarthritis (e.g., primary osteoarthritis is usually bilateral and often symmetrical; severe osteoarthritic changes of one hip while the opposite appears perfectly normal should alert you to the possibility of secondary osteoarthritis).

Erosive Osteoarthritis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree