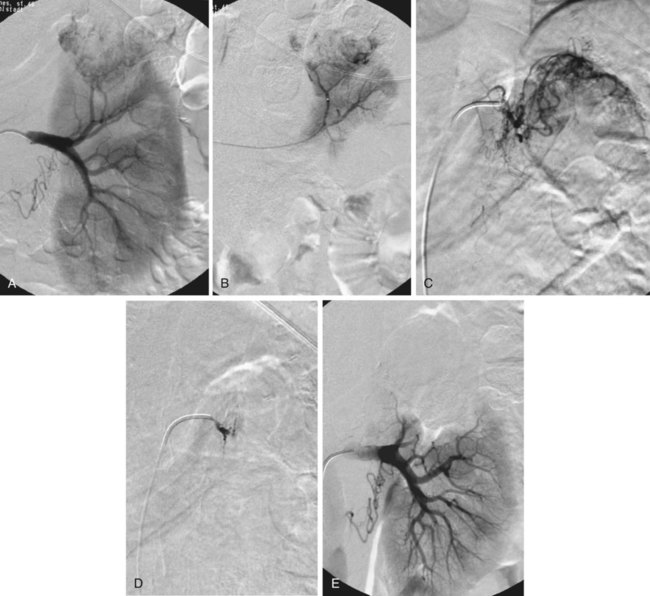

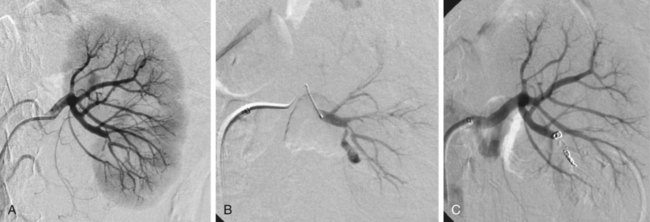

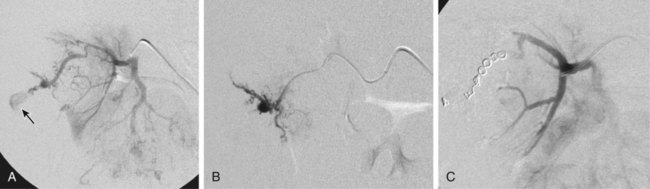

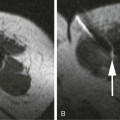

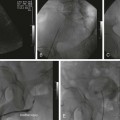

Partial tumor ablation by embolization (Fig. 60-1) is preferred in patients who have a tumor in a single functioning kidney. Partial embolization has also been used as a preparation for thermal ablation of a circumscribed peripheral malignant tumor to reduce the risk of postprocedural bleeding after radiofrequency ablation or to enhance its efficacy.1 There is more published experience of renal artery embolization for ruptured or bleeding benign renal tumors such as angiomas and particularly angiomyolipomas.2 The latter have a tendency to grow during pregnancy, and prophylactic embolization may be performed in women who wish to become pregnant to prevent major bleeding during pregnancy. In benign lesions, a partial embolization is preferable whenever possible. Total renal embolization, including bilateral embolization in some cases, may be indicated in patients with massive protein loss in nephrotic syndrome or other complications of end-stage renal failure such as intractable hypertension. Other indications for total renal embolization are failing kidney transplants, as an alternative to surgical removal in cases of graft intolerance syndrome, and persistent urinary leaks in failing kidneys.3 Very rarely, partial defunctionalization has been described in cases with segmental arterial stenosis and hypertension where the responsible segmental artery was embolized.4 Alternatively, these patients may undergo intrarenal percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) using small balloons. Unfortunately, the main causes of traumatic renal hemorrhage are iatrogenic in origin and represent the majority of cases of traumatic renal hemorrhage in Europe. They include renal biopsies in native and transplant organs, percutaneous techniques such as percutaneous nephrostomy (Fig. 60-2), nephrolithectomy, and percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty (PTRA), where direct arterial perforation by the guidewire tip has been described.5 Also, indirect methods such as shockwave lithotripsy can lead to renal trauma requiring embolotherapy. Although iatrogenic hemorrhage is relatively common, few cases require treatment (0.3%-1% of percutaneous renal interventions6 and 0.5% of percutaneous biopsies7). Moreover, although hemorrhage that requires treatment is unusual, temporary and self-limiting bleeding or AV fistulas occur in up to one third of percutaneous renal procedures.7 Since the introduction of partial nephrectomy techniques, bleeding after partial surgery has become a significant cause of iatrogenic hemorrhage. Approximately 2% of patients who undergo partial nephrectomy develop postsurgical bleeding, and most of them require percutaneous embolization.8 Rarely, benign tumors such as angiodysplasias, angiomas, or angiomyolipoma (Fig. 60-3) may cause spontaneous—sometimes substantial—bleeding (Wunderlich syndrome)9 and may undergo embolization. In a few cases, they may also develop hypertension. As a special problem, true and false aneurysms of the mainstem renal artery10 may occur that may be prone to rupture or serve as an embolic source for renal infarction. There is a general consensus that a diameter of 20 mm is a threshold for treatment; smaller aneurysms may undergo treatment if severe hypertension is present and difficult to treat. Central renal artery aneurysms require treatment by coil placement or, if possible, exclusion by the use of stent grafts. Peripheral (pseudo)aneurysms may be due to trauma or systemic diseases such as polyarteritis nodosa. Peripheral aneurysms are best treated by exclusion, coil placement, or medical adhesive (cyanoacrylate, “glue”) deposition. The most difficult location for treatment of renal artery aneurysms is at the site of a renal artery bifurcation (or trifurcation), because exclusion of the aneurysm may require occlusion of one or more segmental arteries. A combination of bare metallic stents with coils, glue, Onyx (ethylene vinyl alcoholic copolymer [ev3/Covidien, Plymouth, Minn.]), or flow-diverting stents may be an option in these challenging locations.10–14

Renal Artery Embolization

Indications

Tumor Embolization

Defunctionalization

Bleeding Control

Renal Artery Aneurysms

Renal Artery Embolization