SONOGRAM ABBREVIATIONS

C Calculus

IVC Inferior vena cava

K Kidney

L Liver

P Pelvis of the kidney

Ps Psoas muscle

R Rib

RRV Right renal vein

S Spine

Sp Spleen

KEY WORDS

Acute Tubular Necrosis (ATN). Acute renal shutdown, often after an episode of low blood pressure (hypotension). Spontaneous and fairly rapid recovery is usual, but the condition can be fatal.

Anuria. No urine production.

Azotemia. Renal failure.

Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy (BPH). As men age, the prostate enlarges. If the prostate gets too big, it may obstruct the urethra and cause renal failure.

BUN. Blood urea nitrogen. See Serum Urea Nitrogen.

Calyx. A portion of the renal collecting system adjacent to the renal pyramid in which urine collects. The calyx is connected to an infundibulum.

Central Echo Complex (CEC, Sinus Echo Complex). The group of central echoes in the middle of the kidney that are caused by fat and the collecting system.

Column of Bertin. A normal renal variant in which there is enlargement of a portion of the cortex between two pyramids. Can mimic a tumor on pyelography or ultrasound.

Cortex. The more peripheral segment of the kidney tissue. Surrounds medulla and sinus echoes.

Creatinine. See Serum Creatinine.

Dehydration. If a patient does not drink enough fluid, the skin becomes lax and the eyes sunken. Renal obstruction may be present but may be missed sonographically because the kidneys are not producing much urine.

Dialysis. Technique for removing waste products from the blood when the kidneys do not work properly. The two common types are hemodialysis and peritoneal.

Hemodialysis. Used in long-term renal failure. The patient’s blood is circulated through tubes outside the body that allow the exchange of fluids and removal of unwanted substances.

Peritoneal Dialysis. A tube is inserted into the abdomen. Fluid containing a number of body constituents is run into the peritoneum, where it exchanges with waste products. A sonogram shows evidence of apparent ascites.

Dysplasia. Condition resulting from obstruction in utero characterized by echogenic kidneys with cysts. Such kidneys function poorly or not at all. Dysplasia is untreatable.

Glomerulonephritis. Medical condition with acute and chronic forms in which the kidneys function poorly owing to inflammation. Usually it is a self-limiting condition if acute, but if chronic, it may require long-term treatment with dialysis or transplantation.

Hydronephrosis. Dilatation of the kidney collecting system due to obstruction at the level of the ureter, bladder, or urethra.

Hydroureter (Ureterectasis). Distension of the ureter with urine, often due to a blockage of the ureter.

Infundibulum (Major Calyx). A tube connecting the renal pelvis to the calyx.

Medulla. Portion of the kidney adjacent to the calyx, also known as a pyramid. It is less echogenic (hypoechoic) than the cortex.

Nephrostomy or Percutaneous Nephrostomy. Tube inserted through the skin into the kidney to drain an obstructed kidney.

Nephrotic Syndrome. Type of medical renal failure, often due to renal vein thrombosis, in which excess protein is excreted by the kidney.

Oliguria. Decreased urine output.

Polyuria. Increased urine output.

Pyelonephritis (Chronic). Repeated infections destroy the kidneys, which become small with some parenchymal areas narrowed by scar formation.

Pyonephrosis. Hydronephrotic collecting system filled with pus.

Pyramids. See Medulla.

Reflux. A backward (retrograde) flow of urine between the urinary bladder and the kidney.

Serum Creatinine. Waste product that accumulates in the blood when the kidneys are malfunctioning.

Serum Urea Nitrogen (SUN) (Blood Urea Nitrogen [BUN]). Waste products that accumulate in the blood when the kidneys are malfunctioning.

Sinus Echo Complex. See Central Echo Complex.

Staghorn Calculus. Large stone located in the center of the kidney.

Ureterectasia. Dilatation of a ureter.

Ureterocele. Congenital partial obstruction of the ureter at the place where it enters the bladder. A cobra-headed deformity of the lower ureter is seen on a pyelogram.

Urinalysis (UA). Laboratory test that evaluates the patient’s urine for a variety of factors. Used in patients with suspected renal failure, urinary tract infections, diabetes, and many other diseases.

RELEVANT LABORATORY VALUES

Blood urea nitrogen: 7 to 20 mg/dL

Creatinine (Cr): 0.6 to 1.3 mg/dL

Oliguria: For an adult, the excretion of less than 400 or 500 mL of urine in a day

Polyuria: For an adult, the excretion of more than ~2,500 mL of urine in a day

Urinalysis:

Protein: Negative to trace

0 to 5 white blood cells per high power field

0 to 2 red blood cells per high power field

Specific gravity: 1.005 to 1.030

Glucose: Negative

The Clinical Problem

Renal failure occurs when the kidneys are unable to remove waste products from the bloodstream. Waste products used as a measure of the severity of renal failure include the serum creatinine level and serum urea nitrogen (or blood urea nitrogen [BUN]) level. Loss of 60% of the functioning parenchyma can exist without elevation of the BUN or creatinine levels, so these laboratory tests are not very sensitive for the early detection of renal failure.

The onset of renal failure is often insidious. The patient may have the condition for months before seeking medical attention with anemia, nausea, vomiting, and headaches. Other symptoms include increased or decreased urine frequency. Renal failure may be the result of either kidney disease or lower genitourinary tract disease within the ureter, bladder, or urethra with obstruction of urine excretion.

MEDICAL RENAL DISEASE

Kidney disease can either be an acute process or a chronic and irreversible one, treatable only by dialysis or transplant. In potentially reversible, short-term renal failure (e.g., acute tubular necrosis or acute glomerulonephritis), the kidneys are normal in size or large. In patients with long-standing renal failure (e.g., chronic glomerulonephritis or chronic pyelonephritis), the kidneys are small and often abnormally echogenic. Many drugs, particularly the aminoglycoside type of antibiotic, can cause medical renal failure.

HYDRONEPHROSIS

By far the most important diagnosis to exclude in patients with renal failure is hydronephrosis. If hydronephrosis is the cause of renal failure, both kidneys are likely to be obstructed unless the patient has some other renal disease coincident with obstruction. Occasionally, obstruction of one kidney may precipitate renal failure if the other kidney is absent or damaged. If obstruction is the sole cause of renal failure, the level of the obstructive site is probably in the bladder or urethra, because bilateral ureteral obstruction is very unusual. Once renal obstruction has been documented, a drainage/decompressive procedure such as bladder catheterization, nephrostomy, or prostatectomy is urgently required to relieve obstruction. If a drainage procedure is not performed and obstruction persists, kidney function will be permanently impaired. Because of its accuracy, ease of use, lack of risk, and lack of ionizing radiation, sonography has replaced retrograde pyelography as the screening procedure of choice for hydronephrosis in renal failure.

DYSPLASIA

In children, the kidneys may function poorly as a result of obstruction in utero. Such damaged kidneys are seen with posterior urethral valves or the prune belly syndrome.

Anatomy

SIZE AND SHAPE

The normal adult kidney as measured by ultrasound is approximately 11 cm in length (see Appendix 29), with the left being slightly larger than the right. The parenchyma is 2.5 cm thick, and the kidney is approximately 5 cm wide.

The kidneys have a convex lateral edge and a concave medial edge called the hilum. The arteries, veins, and ureter enter the hilum.

LOCATION

The kidneys are located retroperitoneally in the lumbar region, between the 12th thoracic and 3rd lumbar vertebrae. The left kidney lies 1 to 2 cm higher than the right. The kidneys rest on the lower two thirds of the quadratus lumborum muscle, on the posterior and medial portion of the psoas muscle, and laterally on the transverse abdominis muscle.

1. The lower pole is more laterally located than the upper pole.

2. The lower pole is more anteriorly located than the upper pole owing to the oblique course of the psoas muscle.

3. The renal hilum is situated in the center of the medial side.

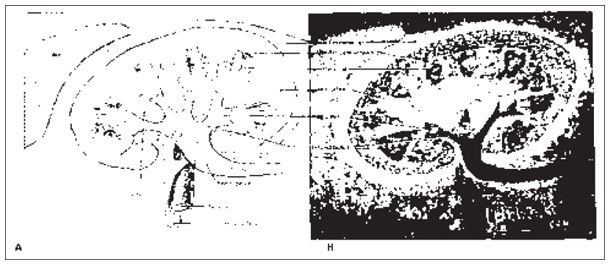

The kidney is surrounded by a well-defined echogenic line representing the capsule in the adult (Fig. 17-1). This line may be difficult to see in the infant or lean people owing to the sparse amount of perinephric fat. At the center of the kidney are dense echoes (the central sinus echo or sinus echo complex) due to renal sinus fat (Fig. 17-1). In the infant or emaciated patient, these echoes may be virtually absent.

PARENCHYMA

The renal parenchyma has two components. The centrally located pyramids, or medulla, are surrounded on three sides by the peripherally located cortex. The medullary zone or pyramid is slightly less echogenic than the cortex (Fig. 17-1). In infants or thin people, a differentiation of medulla from cortex may be very obvious, but in other healthy adults, this separation may be undetectable.

Organ echogenicity from greatest to least in the healthy patient is as follows: renal sinus, pancreas, liver, spleen, renal cortex, and renal medullary pyramids. In healthy adults, the renal cortex should be hypoechoic, or at most isoechoic, to the liver.

SHAPE VARIANTS

The spleen may squash the left kidney, causing a flattened outline or distorted outline so that the lateral border bulges, creating what is termed a dromedary hump (see Fig. 17-9). The renal border may show subtle indentations known as fetal lobulations.

VASCULAR ANATOMY

See Figures 17-1, 17-4, and 22-1.

Renal Veins

The renal veins, which are large, connect the inferior vena cava with the kidneys and lie anterior to the renal arteries. The left renal vein has a long course and passes between the superior mesenteric artery and the aorta (see Fig. 6-12).

Renal Arteries

The renal arteries lie posterior to the renal veins. They may be multiple and too small to visualize, but if only one artery is present, visualization is relatively easy. The right renal artery is longer than the left and passes posterior to the inferior vena cava. The main renal artery gives rise to a dorsal and a ventral branch. These branch first into the interlobar arteries, then into the arcuate arteries (see Fig. 22-1), and finally into the tiny interlobular (cortical) arteries. Typical arterial flow patterns in the renal artery are shown in Figure 22-4.

URETERS

See Chapter 20.

URINARY BLADDER

See Chapter 20.

Figure 17-1. ![]() Major structures of the left kidney. A. Coronal anatomic view. B

Major structures of the left kidney. A. Coronal anatomic view. B

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree