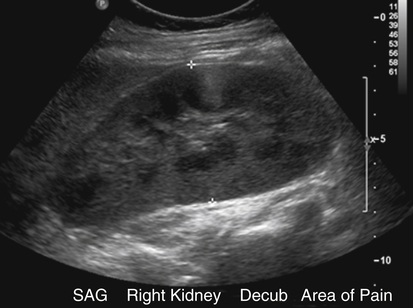

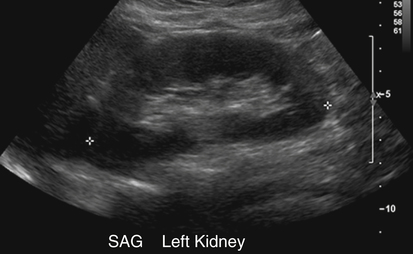

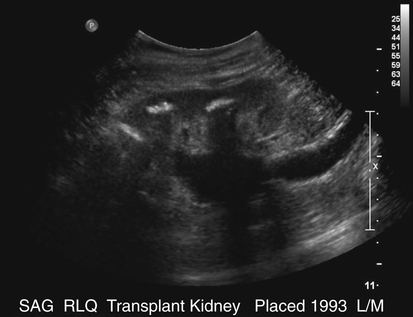

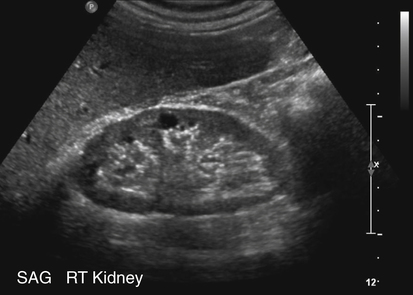

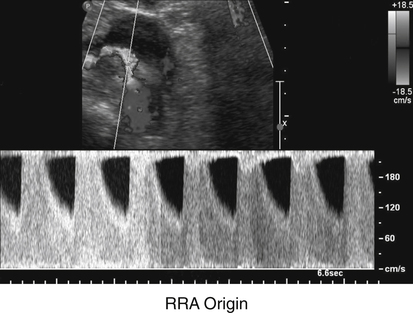

• Describe the typical causes and sonographic appearance of hydronephrosis. • List the common causes and characteristics of acute glomerulonephritis. • Describe the etiology and sonographic appearance of papillary necrosis. • Differentiate between acute and chronic renal failure sonographically. • Describe the Doppler characteristics typically found with renal artery stenosis. • Describe what may cause acute tubular necrosis. • Describe the sonographic appearance of pyonephrosis. • Differentiate between acute, chronic, emphysematous, and xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis sonographically. • Describe possible causes and sonographic appearances of renal abscesses. • Describe the sonographic appearance of a typical fungal infection. Sonographic assessment for renal failure should include a thorough investigation of the genitourinary system with a search for signs of obstruction, tumors, anatomic abnormalities, calculi, infection, stenosis, and decreased renal vascular flow. The sonogram should be initiated with B-mode technology for assessment of kidney size and sonographic characteristics. Next, a Doppler evaluation (color and pulsed-wave) of the renal vascular system should be performed for determination of patency. Abnormal Doppler signals that suggest decreased vascular flow include high systolic peak velocities, low or no diastolic flow, turbulence, and the tardus parvus effect (dampening of the waveform).1 The distention of the renal pelvis and calyces found in patients with significant hydronephrosis causes overall renal enlargement. Sonographically, a hydronephrotic kidney manifests with a group of anechoic, fluid-filled spaces within the renal sinus (Figs. 6-3 and 6-4). Acute obstruction may initially cause the kidney to cease to excrete urine, which delays the onset of any renal dilation. Echogenic calculi (with or without shadowing) may be located throughout the genitourinary system. Smaller stones blend into the echogenic renal sinus. Previous obstruction, pregnancy, megaureter, or an extremely full bladder also causes normal calyceal dilation. Chronic obstruction causes atrophy of the renal parenchyma. Hydronephrosis manifests with a slight distention of the collecting system displaying a small separation of the calyceal pattern (splaying).2 As hydronephrosis progresses, the collecting system dilates with fluid extending into the major and minor calyceal systems (bear-claw effect).2 Severe hydronephrosis manifests with massive dilation including the renal pelvis. It is associated with cortical thinning or loss of the renal parenchyma. With assessment for hydronephrosis, parapelvic cysts should be ruled out. Generally, dilated calyces have a more echogenic margin than a parapelvic cyst. An extra renal pelvis should also be considered because it can be confused with hydronephrosis owing to its large cystic appearance within the renal hilum. Acute glomerulonephritis is an inflammation of the renal glomeruli that frequently occurs as a late complication of an infection, typically of the throat (pharyngitis).3 Glomerulonephritis is characterized by bilateral inflammatory changes in the glomeruli that are not the result of infection of the kidneys. It is more common in males than in females and is more common in children than in adults.4 Symptoms are variable and include foggy urine, history of recent fever, sore throat, joint pains, peripheral edema (e.g., face, ankles), nausea, oliguria, anemia, azotemia, and hypertension. Laboratory findings may include hematuria, proteinuria, decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR), increased BUN value, and increased serum creatinine level.5 Inflammation and scarring of the glomeruli result in an inability to filter the blood properly to make urine.6 The inflammation and scarring lead to poor kidney function and ultimately renal failure. Acute glomerulonephritis commonly leads to chronic glomerulonephritis. Chronic glomerulonephritis develops slowly and may not be detected until the kidneys fail, which could take 20 to 30 years.3 Chronic glomerulonephritis is characterized by irreversible and progressive glomerular fibrosis that leads to a reduction in the GFR and a retention of uremic toxins.7 Chronic glomerulonephritis leads to chronic renal failure, end-stage renal disease, and eventually death. It requires long-term treatment with dialysis or transplantation. The renal papillae are the rounded tips at the apex of each renal medullary pyramid. The renal papillae face toward the renal hilum and represent the confluence of the collecting ducts from each nephron within that pyramid. Necrosis of the renal papillae causes hydronephrosis from the sloughed papillae obstructing the calyces. Hydronephrosis is also caused by sloughed papillae obstructing the ureters. Any narrowed area can make a nesting spot for sloughed papillae, leading to obstruction. The sloughed papillae calcify, further increasing the potential for obstructive hydronephrosis. The actual sloughing of the renal papilla is the result of vascular ischemia, which leads to necrosis of the renal medullary pyramids.8 Papillary necrosis is the result of medullary vasculature being compressed with inflammation. Patients with diabetes and females are more prone to papillary necrosis.8 Patients have fever from infection, flank or abdominal pain, hypertension (from renal ischemia), dysuria, and hematuria. Laboratory results typically show a positive urine culture (from passage of sloughed papillae), proteinuria, pyuria, bacteriuria, and low urine-specific gravity. Papillary necrosis can be a complication of severe pyelonephritis. Infection is also a complication of papillary necrosis because the necrotic papillae act as an origin for infection and the formation of stones. Papillary necrosis has the potential to lead to renal failure and ultimately death. Papillary necrosis is visualized sonographically as clubbing of the calyces as a result of obstruction caused by sloughed papillae.5 Obstruction caused by sloughed papillae manifests sonographically with signs of hydronephrosis. The sonographic evaluation should include a search for calculi or obstruction, including an evaluation for stones large enough to produce a shadow and hydronephrosis resulting from papillary necrosis. Round or triangular cystic collections within the medullary pyramids may be visible. A sloughed papilla, when visualized, appears as an echogenic, nonshadowing structure within the renal collecting system. If the papillae calcify, acoustic shadowing would be shown (Fig. 6-5). Severe papillary necrosis may cause the papillae to be replaced with urine-filled sacs.9 Papillary necrosis would then appear as multiple cystic structures in the renal pyramid region that do not communicate with the renal pelvis. Renal failure can be categorized as either acute or chronic. Acute symptoms are sudden and severe, whereas chronic symptoms are slow and irreversible. In both acute and chronic forms of renal failure, the excretory and regulatory functions of the kidneys are decreased. Obstructive causes of renal failure are treatable and are an important diagnosis during patient evaluation. Renal disease is considered end-stage when the kidneys are unable to fulfill more than 10% of their normal function.3 At this point, dialysis may be necessary. The term “acute kidney injury” represents the entire spectrum of acute renal failure (risk, injury, and then failure).10 Acute kidney injury is the generic term used to define an abrupt decrease in renal function resulting in retention of nitrogenous waste (BUN and creatinine). An acute kidney injury may cause a decrease in renal blood flow and produce renal parenchymal insult or obstruction. Reduction of renal blood flow causes a decrease in the GFR, which leads to retention of water and salts. This retention causes oliguria, concentrated urine, and a progressive inability to excrete nitrogenous wastes. Decreased renal blood flow leads to ischemia and eventually to cell death. Recovery from an acute kidney injury depends on restoration of normal renal blood flow. Earlier blood flow normalization leads to a better prognosis for recovery of renal function. Patients with an acute kidney injury may have symptoms of hypovolemia, hypertension, edema, oliguria, and hematuria.11 Laboratory results may include increased WBCs, increased creatinine levels, and increased BUN values. An acute kidney injury may have different causes depending on the stage of the disease. Prerenal causes of acute renal failure are the result of hypoperfusion of the kidney. Renal causes result from parenchymal diseases, such as acute glomerulonephritis, renal vein thrombosis, and acute tubular necrosis.11 Postrenal causes of acute renal failure are the result of obstruction. Chronic renal failure that necessitates dialysis or transplantation is referred to as end-stage renal disease. Failed kidneys are unable to regulate electrolyte, fluid, and acid-base balances.12 In chronic renal failure, dialysis is necessary until a kidney transplant is performed. Chronic renal failure has many different causes, including infection, diabetes, hypertensive vascular disease, congenital and hereditary disorders, toxic nephropathy, and obstructive nephropathy.12 Renal failure produces no symptoms early in the course of the disease. The most common cause of chronic renal failure is diabetes mellitus.5 Glomerulonephritis, interstitial nephritis, and chronic upper urinary tract infection are also causes of chronic renal failure. Patients with chronic renal failure may have malaise, increased concentration of urea in blood, fatigue, anorexia, nausea, hypotension, and hyperkalemia. Laboratory findings include decreased GFR, hyperkalemia, elevated BUN and serum creatinine levels, and anemia (from loss of erythropoietin production). Initially, the kidneys are enlarged; but over time, patients with chronic renal disease have a progressive decrease in renal size bilaterally. With unilateral involvement, the affected kidney is almost impossible to visualize. Sonographically, patients with chronic renal disease have increased cortical echogenicity with poor corticomedullary differentiation. With end-stage renal disease, the kidneys continue to become smaller and more echogenic, and the renal parenchyma becomes thinned (Fig. 6-6). Renal artery stenosis is a common cause of renovascular hypertension. Renal artery stenosis also causes chronic renal insufficiency and end-stage renal disease. Atherosclerosis is a common cause of renal artery stenosis in older patients. As the renal artery lumen progressively narrows, renal blood flow decreases and eventually compromises renal function and structure. In patients with renal artery stenosis, chronic ischemia causes atrophy with decreased tubular cell size, patchy inflammation and fibrosis, and intrarenal arterial medial thickening.13 Renal artery stenosis causes a decrease in GFR when arterial luminal narrowing exceeds 50%.13 Renal artery stenosis results in hypertension and a progressive loss of renal function; when bilateral, renal artery stenosis causes renal failure. Renal artery stenosis is a common vascular complication of transplantation, and it affects the renal function. Spectral Doppler and color flow evaluations are helpful in showing reduced or no flow to the involved kidney or renal area. Duplex evaluation combines B-mode sonography with pulsed Doppler to obtain flow velocity data. In healthy patients, a steep systolic upstroke is seen with a second small peak in early systole and significant diastolic flow. Patients with renal artery stenosis have abnormal Doppler waveforms. Specifically, Doppler analysis in patients with renal artery stenosis shows high systolic peak velocities (Fig. 6-7) with little or no diastolic flow at the site of stenosis. Flow disturbances can occur 1 cm distal to the stenosis.1 The stenotic area is typically at the junction of the renal artery and the aorta. The tardus parvus effect (seen distal to the stenosis) is apparent in the intrarenal vasculature of patients with renal artery stenosis. The tardus parvus effect is the dampening of the distal waveform–lengthened systolic rise time or slow systolic acceleration (tardus)/lowering and rounding of the systolic peak (parvus).1

Rule Out Renal Failure

Hydronephrosis

Sonographic Findings

Acute Glomerulonephritis

Papillary Necrosis

Sonographic Findings

Renal Failure

Acute Kidney Injury (Acute Renal Failure)

Chronic Renal Failure

Sonographic Findings

Renal Artery Stenosis

Sonographic Findings

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Rule Out Renal Failure