Sarcoidosis is a systemic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology that affects multiple organs and is characterized by the formation of noncaseating granulomas. Intrathoracic lymph node and pulmonary parenchymal involvement occurs in more than 90% of cases. The granulomas have a characteristic distribution along the lymphatics in the pleura, interlobular septa, and bronchovascular bundles. They may resolve spontaneously or with treatment or progress to fibrosis.

Etiology

The etiology is unknown. The presence of familial clustering and the racial variation in incidence suggest an important genetic contribution. Clustering during certain times, in specific regions, and in close acquaintances of affected patients and variations in incidence with season indicate that environmental influences also have an important effect. The nature of the immunologic disturbances suggests that sarcoidosis results from exposure of genetically susceptible individuals to specific environmental agents that trigger an exaggerated cellular immune response leading to granuloma formation. Whether coincidental or linked via common susceptibility or exposure, sarcoidosis has been described in association with a variety of connective tissue disorders, including rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and progressive systemic sclerosis.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Sarcoidosis may occur at any age, but the disease is recognized most commonly in patients 20 to 40 years old and is slightly more common in women. A second peak in incidence occurs in women older than 50 years.

There is considerable variation in the reported incidences and prevalences in different populations. Sarcoidosis is particularly common in African Americans, especially women. It is common in Scandinavian countries and Ireland and is seldom reported in South America and China. The estimated lifetime incidence of sarcoidosis in the United States is 2.4% for African Americans and 0.85% for whites. African Americans also have more severe lung disease than whites on presentation and a worse prognosis. Sarcoidosis also is more prevalent in Irish living in London than in native Londoners and more prevalent in natives of Martinique living in France than in indigenous French. Although the incidence in most nations of continental Europe is less than 1 per 100,000, the incidence in Scandinavian countries, such as Sweden (64 per 100,000) and Finland (11 per 100,000) is considerably higher. Approximately 1 per 100,000 new cases of sarcoidosis are reported in Japan. Overall mortality from sarcoidosis is 1% to 5%.

Clinical Presentation

Approximately 30% to 50% of patients are asymptomatic, sarcoidosis being first suspected based on the presence of bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy on routine chest radiographs, and approximately 50% present with pulmonary symptoms. The most common pulmonary complaints are dyspnea, cough, and chest pain. The mechanism for the development of chest pain is unclear. Constitutional symptoms are common and include weight loss, fatigue, weakness, and malaise. Symptoms often develop insidiously and are frequently associated with evidence of multisystem involvement, most commonly the lungs, heart, skin, and eyes. In a study of 189 patients, 52% presented with pulmonary symptoms (26% with pulmonary symptoms alone), 13% with skin concerns, 6% with systemic symptoms, and 16% with other manifestations. A characteristic acute manifestation is Löfgren syndrome, a triad of bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, erythema nodosum, and polyarticular arthralgia, which is seen in 20% to 50% of patients with acute disease. An acute onset of symptoms, usually with erythema nodosum, is particularly common in Scandinavian, Puerto Rican, and Irish women.

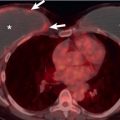

Five percent of patients with sarcoidosis develop pulmonary arterial hypertension. The severity of pulmonary hypertension does not correlate well with the degree of pulmonary fibrosis and has been reported as an early primary manifestation of sarcoidosis, suggesting that other mechanisms may play a role. Such mechanisms include extrinsic compression of large pulmonary arteries or veins by enlarged lymph nodes, granulomatous vascular involvement, and pulmonary vasoconstriction by vasoactive factors.

Myocardial involvement is evident at autopsy in approximately 25% of patients with sarcoidosis, but only approximately half of these patients have clinical evidence of myocardial involvement during their lifetime. In the United States cardiac involvement accounts for 13% to 25% of deaths from sarcoidosis. In Japan sarcoid heart disease is more common and responsible for 85% of deaths from sarcoidosis. The most common cardiac manifestation of sarcoidosis is complete heart block. Other findings include atrial arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, ventricular aneurysm, rhythm disturbances, cor pulmonale caused by pulmonary hypertension, valvular regurgitation, or a combination of these processes. Pericardial effusions occur in approximately 5% to 15% of patients with sarcoidosis, but they are usually small.

Ocular involvement manifests in 25% to 60% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis. The most common ocular manifestation is uveitis. More than 80% of uveitis cases manifest before or within 1 year after the onset of systemic disease. Ocular disease may progress to severe visual impairment or even blindness.

Cutaneous involvement occurs in approximately 25% of patients and may be specific (granulomas present pathologically) or nonspecific. The most frequent nonspecific abnormality is erythema nodosum. This inflammatory reaction is a form of panniculitis that most commonly involves the shins and is characterized by the development of crops of transient, nonulcerating nodules that are generally tender, multiple, and bilateral. Erythema nodosum is the hallmark of acute sarcoidosis and is associated with a high rate of spontaneous resolution. Lupus pernio (“purple lupus”) is a chronic plaque-type, indurated, brown-to-purple lesion that progresses slowly and is usually located on the face, neck, shoulders, and digits and sometimes on the mucous membrane of the nose; it is often associated with involvement of the nasal bones. Large plaques resembling psoriasis may develop over the trunk or extremities. Lupus pernio and plaques generally are associated with a chronic course and seldom, if ever, resolve completely.

Granulomas can be found in the liver and spleen at autopsy in approximately 75% of patients; however, palpable enlargement of these organs is seen in only 20%. Most such disease causes no symptoms. Occasionally, hepatic involvement may be associated with jaundice, chronic cholestasis, cirrhosis, and portal hypertension.

Inflammatory arthralgia, which may be monarticular or polyarticular, occurs in 25% to 40% of patients with sarcoidosis. The joints most commonly affected are the knees, ankles, elbows, and wrists. Symptoms are usually self-limited but occasionally recur. True arthritis is uncommon.

Clinical or functional evidence of renal disease is uncommon despite the fact that granulomas are found in the kidneys in 5% to 20% of autopsied patients. Renal complications are usually secondary to the abnormal calcium metabolism in patients with sarcoidosis, which may result in hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, and occasionally nephrocalcinosis, urolithiasis, or hypercalcemic renal failure. Hypercalcemia occurs in about 2% to 10% of patients; hypercalciuria is about three times more frequent. These abnormalities are due to dysregulated production of 1,25-(OH) 2 -D 3 (calcitriol) by activated macrophages and granulomas. Aside from the renal effects of hypercalcemia, metastatic calcification can occur in organs and tissues other than the kidney, including the eyes, lungs, and blood vessels.

Neurologic symptoms occur in 5% of patients with sarcoidosis. The most common manifestations are cranial nerve palsies, headache, seizures, sensory and motor deficits, cerebellar symptoms, and neuropsychological deficits. Cranial palsies are seen in 50% of patients with neurologic involvement. Although any cranial nerve can be affected, the facial nerve is the most commonly involved. Psychiatric manifestations include delirium, psychosis, and personality change.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

Sarcoidosis is characterized by accumulation of large numbers of activated macrophages and T lymphocytes. These cells release Th1-predominant cytokines, including interferon-γ, tumor necrosis factor-α, and various interleukins, and result in granuloma formation. The etiology of the initial stimulus and the reason why the granuloma formation is persistent are unknown.

The histologic diagnosis of pulmonary sarcoidosis relies on three main findings: (1) the presence of tight, well-formed granulomas and a rim of lymphocytes and fibroblasts in the outer margin of granulomas; (2) perilymphatic interstitial distribution of granulomas; and (3) exclusion of an alternative cause. The pathologic hallmark of sarcoidosis is the granuloma, composed of a central core of tightly clustered epithelioid histiocytes and occasional multinucleated giant cells surrounded by varying quantities of fibroblasts and collagen ( Fig. 31.1 ). Most granulomas are nonnecrotizing; however, some may show a small amount of central fibrinoid necrosis. Fibroblasts are present at the periphery of more “mature” granulomas, and it seems that the fibrosis begins at this site. In this circumstance concentric lamellae of collagen can be seen to separate the histologically “active” central portion of the granuloma from the adjacent tissue. With time the fibrosis proceeds inward until the entire granuloma is converted into a scar. This pattern of peripheral lamellar fibrosis is characteristic of healing sarcoidosis and is itself evidence in favor of the diagnosis.

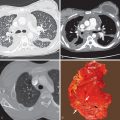

The sarcoid granulomas have a characteristic perilymphatic distribution, pulmonary involvement being characteristically most prominent in the peribronchovascular, interlobular septal, and pleural interstitial tissue ( Fig. 31.2 ). In the early stages granulomas are discrete and histologically “active”; as the disease progresses, they often become confluent and undergo fibrosis, which results in more or less diffuse interstitial thickening. The parenchymal interstitium also may be affected, although typically much less than in peribronchovascular, septal, and pleural locations. Possibly, because of the prominent peribronchovascular ( Fig. 31.3 ) and septal location of the granulomatous inflammation, involvement of pulmonary arteries and veins is common.

The gross appearance of pulmonary sarcoidosis depends on the stage and severity of disease. In the early, milder forms in which inflammation is most prominent in relation to peribronchovascular, interlobular, and pleural connective tissue, the appearance can resemble lymphangitic carcinomatosis. As disease progresses, involvement of the parenchymal interstitium becomes more evident, and entire lobules can be replaced by granulomas and fibrous tissue. This process is usually most severe in the upper lobes, where it can take the form of more or less solid areas of fibrous tissue associated with traction bronchiectasis. The latter may be the site of aspergilloma formation.

Lymph node involvement is characterized by more or less diffuse replacement of the node by granulomas, often with a variable histologic appearance. Initially, the granulomas are discrete and appear “active”; as in pulmonary disease, however, they tend to become confluent and undergo progressive fibrosis over time. In advanced disease this process can result in completely fibrotic nodes in which granulomas are difficult to recognize.

Lung Function

Most patients with sarcoidosis and abnormal lung function have restrictive abnormalities; however, many have an obstructive deficit as well. In a few patients the pattern is solely obstructive. The frequency of airflow obstruction is greater in patients with extensive fibrosis, older age, and smoking history. Cigarette smoking seems to be the most important determinant of airflow obstruction in these patients, although pulmonary fibrosis also plays an important role. Restrictive lung function is manifested by a reduction in total lung capacity and vital capacity and obstructive lung function by reduction in the forced expiratory volume at 1 second–to–forced vital capacity ratio and by air-trapping (increase in the residual volume–to–total lung capacity ratio). Sarcoid patients also may have impairment in gas transfer as assessed by the carbon monoxide diffusing capacity and an increase in the alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient.

Manifestations of the Disease

Radiography

Radiographic abnormalities can be classified into five stages, as follows:

Stage 0: No demonstrable abnormality

Stage I: Hilar and mediastinal lymph node enlargement without parenchymal abnormality ( Fig. 31.4 )

Fig. 31.4

Stage I sarcoidosis: radiographic findings. Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a man with sarcoidosis shows right paratracheal, aorticopulmonary window, and symmetric bilateral hilar lymph node enlargement.

Stage II: Hilar and mediastinal lymph node enlargement plus parenchymal abnormality ( Fig. 31.5 )

Fig. 31.5

Stage II sarcoidosis: radiographic findings. (A) Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a man with sarcoidosis shows right paratracheal, aorticopulmonary window, and symmetric bilateral hilar lymph node enlargement and small round and irregular opacities in the upper lung zones. Note medial deviation of the gastric bubble owing to splenomegaly. (B) Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a different patient with sarcoidosis shows more extensive parenchymal abnormalities characterized by small nodular opacities involving mainly the upper and middle lung zones. Symmetric bilateral hilar and right paratracheal lymphadenopathy also is noted.

Stage III: Parenchymal abnormality alone ( Fig. 31.6 )

Fig. 31.6

Stage III sarcoidosis: radiographic findings. Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a man with sarcoidosis (same patient as Fig. 31.5A 4 years later) shows a reticulonodular pattern involving mainly the upper and middle lung zones. There is no evidence of hilar or mediastinal lymph node enlargement.

Stage IV: Advanced fibrosis with evidence of reticulation, architectural distortion, hilar retraction, and occasionally honeycombing ( Fig. 31.7 )

Fig. 31.7

Stage IV sarcoidosis: radiographic findings. Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a middle-aged woman with sarcoidosis shows a coarse reticulonodular pattern involving mainly the upper lobes. Note bilateral elevation of the hila and distortion of the lung architecture characteristic of fibrosis.

In a multicentric case-control study of 736 patients with sarcoidosis, approximately 8% had stage 0, 40% had stage I, 37% had stage II, 10% had stage III, and 5% had stage IV disease. The main utility of this staging system is in predicting outcome. Spontaneous remissions occur in 55% to 90% of patients with stage I disease, in 40% to 70% of patients with stage II, in 10% to 20% of patients with stage III disease, and in 0% of patients with stage IV sarcoidosis.

The radiographic staging scheme applies only to the chest radiograph. High-resolution computed tomography (CT) may show parenchymal abnormalities in patients with radiographic stage I disease; these abnormalities tend to be relatively mild and are unlikely to change the prognosis in these patients.

Lymph Node Enlargement Without Pulmonary Abnormality

Lymph node enlargement without parenchymal disease is seen on the initial chest radiograph in approximately 40% of patients. The combination of bilateral hilar and right paratracheal lymph node enlargement is a characteristic and common manifestation (see Fig. 31.4 ). Less common sites with lymphadenopathy evident on the radiograph include the aorticopulmonary window, subcarinal region, and anterior mediastinum. Hilar lymph node enlargement is usually bilateral and symmetric. Unilateral enlargement is uncommon, being reported in only 3% to 5% of proven cases. Occasionally, hilar nodal enlargement is sufficient to compress adjacent bronchi and lead to atelectasis (most commonly involving the middle lobe). Calcification of hilar lymph nodes is radiographically apparent in approximately 5% of patients initially and in more than 20% after 10 years of follow-up. Eggshell calcification of hilar and mediastinal nodes may occur but is uncommon ( Fig. 31.8 ).

As with other interstitial diseases, the lungs can be involved by sarcoidosis in the absence of a demonstrable abnormality on the chest radiograph. The chest radiograph is normal (stage 0) in about 10% of patients who have biopsy-proven pulmonary sarcoidosis. Similarly, in a study of 21 consecutive patients with stage I disease who underwent surgical lung biopsy, typical sarcoid granulomas were present in the lung parenchyma in all; however, the extent of granulomatous inflammation was significantly less than that seen in lung biopsy specimens of patients who had radiographic evidence of diffuse lung involvement. As might be expected, parenchymal abnormalities are seen more commonly on high-resolution CT scans than on radiography.

Approximately 55% to 90% of patients who have stage I disease show complete radiographic resolution. Occasionally, enlarged hilar and mediastinal nodes regress to normal size, only to undergo enlargement again at a later date. Node enlargement can persist unchanged for many years.

Diffuse Pulmonary Disease With or Without Lymph Node Enlargement

Parenchymal disease is seen on the chest radiograph at initial evaluation in approximately 55% of patients. This includes approximately 35% to 40% of patients with parenchymal disease associated with enlarged nodes (stage II), 10% with parenchymal disease not associated with enlarged nodes (stage III), and 5% with interstitial fibrosis (stage IV).

The parenchymal abnormalities are typically bilateral and symmetric and involve mainly the upper lung zones in 50% to 80% of patients (see Figs. 31.5 and 31.6 ). Occasionally, disease is asymmetric, unilateral, or diffuse ( Fig. 31.9 ). The most frequent patterns are nodular and reticulonodular; less commonly, a reticular pattern, airspace consolidation, or, rarely, ground-glass opacities predominate.

Nodular Pattern.

A nodular pattern is present on chest radiographs in 30% to 60% of patients. The nodules usually have irregular margins and involve mainly the middle and upper lung zones. They range from 1 to 10 mm in diameter, although most measure less than 3 mm (see Fig. 31.5 ).

Reticulonodular Pattern.

A reticulonodular pattern is present in 25% to 50% of patients who have radiographically evident parenchymal abnormalities. The pattern may result from a combination of nodules and thickening of the interlobular septa or a combination of nodules and intralobular linear opacities (see Fig. 31.9 ).

Parenchymal Consolidation.

Parenchymal consolidation is present in 10% to 20% of patients who have sarcoidosis and radiographically evident parenchymal disease. The consolidation typically has a bilateral and symmetric distribution involving mainly the middle and upper lung zones ( Fig. 31.10 ).

Fibrosis.

Fibrosis is seen at presentation in approximately 5% of patients and eventually develops in 20% to 25% of patients. The fibrosis in sarcoidosis typically involves mainly the perihilar regions of the middle and upper lung zones ( Fig. 31.11 ). It is usually associated with superior retraction of the hila, distortion of the bronchovascular bundles, bulla formation, traction bronchiectasis, and compensatory overinflation of the lower lobes.

Cavitation and Mycetoma Formation.

Cavitation is an uncommon manifestation of sarcoidosis and usually is seen in association with other parenchymal abnormalities. The cavities may resolve spontaneously or be complicated by superimposed infection or fungus ball formation (mycetoma). Mycetomas develop in 1% to 3% of patients with sarcoidosis. They typically occur in the upper lobes in patients with advanced (radiographic stage III or IV) sarcoidosis ( Fig. 31.12 ). The mycetomas are most often located in foci of bronchiectasis but also may be seen in bullae or cavities of uncertain origin.

Pleural Disease.

Pleural effusion has been documented in about 3% of patients. Affected individuals typically have moderately advanced pulmonary sarcoidosis; nonnecrotizing granulomas are often identified on pleural biopsy. The effusion tends to clear in 4 to 8 weeks but may progress to chronic pleural thickening. Spontaneous pneumothorax has been estimated to occur in about 1% of patients.

Cardiovascular Disease.

Although abnormalities of the heart, pericardium, and pulmonary vasculature are commonly seen on histologic examination, they are usually of insufficient severity to cause radiographic manifestations. Radiographically evident enlargement of the cardiac silhouette may be the result of cardiomyopathy, valvular disease, pericardial effusion, or left ventricular aneurysm. Pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale, caused by a combination of obliteration of the pulmonary vascular bed and hypoxic vasoconstriction, tend to occur in the late stage of the disease.

Computed Tomography

Pulmonary Manifestations

The high-resolution CT findings of pulmonary sarcoidosis closely reflect the histologic findings and show a characteristic pattern of small nodules in a perilymphatic distribution. The nodules are seen mainly adjacent to the bronchi and pulmonary arteries and veins and along the interlobular septa, interlobar fissures, and costal subpleural regions and result in nodular thickening of these structures ( Figs. 31.13 and 31.14 ). Sarcoid granulomas along the peribronchovascular interstitium extend to the peribronchiolar interstitium, resulting in prominence of the centrilobular core and centrilobular nodules (see Fig. 31.14 ). Although the distribution of sarcoidosis is typically perilymphatic, there is considerable variation in the extent to which it affects the various perilymphatic compartments. In some patients it is predominantly peribronchial or perivascular and in others predominantly subpleural; only occasionally does it involve mainly the interlobular septa. Although nodular septal thickening is commonly present, it is seldom extensive ( Fig. 31.15 ), as this pattern is more commonly seen with lymphangitic carcinomatosis. Occasionally, the nodules may be small and result in a diffuse miliary pattern ( Fig. 31.16 ) or involve predominantly or exclusively the subpleural lung regions. Conglomeration of subpleural granulomas in the costal regions may resemble pleural plaques (pseudoplaques) ( Fig. 31.17 ).