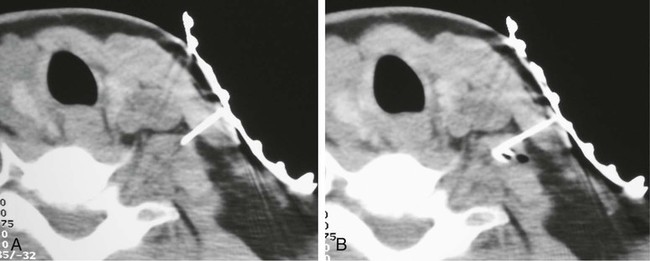

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is a constellation of symptoms caused by compression of neurovascular structures as they traverse the superior thoracic outlet.1 TOS can have neural components, vascular components, or both, and its causes include trauma, repetitive stress injury, congenital abnormalities, or combinations of these (e.g., congenital cervical rib combined with repetitive stress injury).2,3 Vascular TOS is straightforward and can be documented by arteriography. Compression of the subclavian vessels leads to swelling, edema, and loss of blood flow to the upper extremity, particularly with exertion. Neurogenic TOS (nTOS) is more ambiguous. In nTOS the brachial plexus is presumably compressed, and such compression gives rise to pain, numbness, heaviness or other dysesthesia, and weakness in the upper extremity.4 Electrodiagnostic studies may be abnormal in nTOS patients, but only in a minority, and results vary over time.5 Given that many conditions (e.g., cervical radiculopathy, cervical spondylosis, shoulder joint and tendon pathology, myofascial pain syndrome, peripheral neuropathy, etc.) can lead to arm or neck pain, diagnosis of nTOS can prove difficult. Treatment of nTOS is also controversial. The brachial plexus can be decompressed by either transaxillary or supraclavicular approaches. A recent case series of 170 patients showed that decompression was successful 65% of the time.6 Interestingly, Landry et al.7 monitored 79 patients with “disputed TOS” who had symptoms of nTOS but no electrodiagnostic confirmation. Fifteen of the patients underwent decompressive surgery at other centers, and the remaining 64 were managed nonoperatively. Outcome was no better or worse with surgery. Given these results, patient selection for surgery is crucial. Jordan and Machleder showed that temporary relaxation of the anterior scalene muscle (ASM) with an injection of local anesthetic can predict which patients will benefit from decompression.8 The ASM lies directly anterior to the trunks of the brachial plexus (Fig. 170-1, A). Presumably, relaxation of the ASM temporarily “decompresses” the plexus, thereby predicting the results of surgical decompression. For the injection to be predictive, anesthesia of the adjacent plexus and sympathetic chain must be avoided. Jordan and Machleder used electromyography to position the needle directly in the ASM. The positive predictive value of their injections was excellent; 30 of 32 (94%) patients who received relief from the temporary block achieved a good outcome from surgical decompression. The negative predictive value was less impressive. Six patients underwent surgery despite a negative ASM block, and 3 (50%) had a good outcome from decompression.8 They also found that chemodenervation with botulinum toxin leads to sustained relief with a duration of 88 days, consistent with the duration of chemodenervation.9 These data are preliminary. Too few patients have proceeded to surgery on the basis of CT-guided ASM injections for sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values to be calculated. However, these injections should be at least as good as electromyelography-guided injections.8 To be clear, pain relief after ASM injection is not the gold standard for the diagnosis of TOS. Congenital abnormalities may compress the neurovascular bundle at the thoracic inlet, or the compression may be distal to the ASM.10 However, pain relief after ASM injection does predict the outcome of surgical decompression.8 A positive response to ASM injection will reassure patients and their surgeons that the operation is likely to be successful, whereas negative responses can spare other patients needless surgery.

Scalene Blocks and Their Role in Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine