1. Germ cell tumors

Intratubular germ cell neoplasia, unclassified type (IGCNU)

Seminoma (including cases with syncytiotrophoblastic cells)

Spermatocytic seminoma (mention if there is sarcomatous component)

Embryonal carcinoma

Yolk sac tumor

Choriocarcinoma

Teratoma (mature, immature, with malignant component)

Tumors with more than one histological type (specify percentage of individual components)

2. Sex cord/gonadal stromal tumors

Leydig cell tumor

Malignant Leydig cell tumor

Sertoli cell tumor

Lipid-rich variant

Sclerosing

Large cell calcifying

Malignant Sertoli cell tumor

Granulosa cell tumor

Adult type

Juvenile type

Thecoma/fibroma group of tumors

Other sex cord/gonadal stromal tumors

Incompletely differentiated

Mixed

Tumors containing germ cell and sex cord/gonadal stromal (gonadoblastoma)

3. Miscellaneous nonspecific stromal tumors

Ovarian epithelial tumors

Tumors of the collecting ducts and rete testis

Tumors (benign and malignant) of nonspecific stroma

All these aspects will be discussed in the following sections of this chapter.

49.2 Diagnosis

49.2.1 Urology Consultation

Testicular cancer generally affects young men in the third or fourth decade of life. The usual clinical presentation of testicular tumors is a painless, palpable testicular mass or diffuse testicular enlargement [15]. In approximately 20 % of cases, the first symptom is scrotal pain, and up to 27 % of patients with testicular cancer may have local pain [1]. Occasionally, trauma to the scrotum may reveal the presence of a testicular mass. Gynaecomastia appears in 7 % of cases and is more common in NSGCTs. Back and flank pain are present in about 11 % of cases [1]. Seminomas and testicular lymphomas may cause orchitis secondary to obstruction of the seminiferous tubules [16].

49.2.2 Serum Markers

Tumor markers play an important clinical role in patient management. In recognition of the clinical utility, serum tumor marker levels are included in the TNM staging classification (S category) (Table 49.2) and the International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group prognostic staging system for metastatic germ cell tumors [17].

Table 49.2

TNM classification for testicular cancer

pT: primary tumor | ||

pTX Primary tumor cannot be assessed (see 1, T—primary tumor) | ||

pT0 No evidence of primary tumor (e.g. histological scar in testis) | ||

pTis Intratubular germ cell neoplasia (carcinoma in situ) | ||

pT1 Tumor limited to testis and epididymis without vascular/lymphatic invasion: tumor may invade tunica albuginea but not tunica vaginalis | ||

pT2 Tumor limited to testis and epididymis with vascular/lymphatic invasion, or tumor extending through tunica albuginea with involvement of tunica vaginalis | ||

pT3 Tumor invades spermatic cord with or without vascular/lymphatic invasion | ||

pT4 Tumor invades scrotum with or without vascular/lymphatic invasion | ||

N: regional lymph nodes clinical | ||

NX Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | ||

N0 No regional lymph node metastasis | ||

N1 Metastasis with a lymph node mass 2 cm or less in greatest dimension or multiple lymph nodes, none more than 2 cm in greatest dimension | ||

N2 Metastasis with a lymph node mass more than 2 cm but not more than 5 cm in greatest dimension, or multiple lymph nodes, any one mass more than 2 cm but not more than 5 cm in greatest dimension | ||

N3 Metastasis with a lymph node mass more than 5 cm in greatest dimension | ||

pN: pathological | ||

pNX Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | ||

pN0 No regional lymph node metastasis | ||

pN1 Metastasis with a lymph node mass 2 cm or less in greatest dimension and 5 or fewer positive nodes, none more than 2 cm in greatest dimension | ||

pN2 Metastasis with a lymph node mass more than 2 cm but not more than 5 cm in greatest dimension; or more than 5 nodes positive, none more than 5 cm; or evidence or extranodal extension of tumor | ||

pN3 Metastasis with a lymph node mass more than 5 cm in greatest dimension | ||

M: distant metastasis | ||

MX Distant metastasis cannot be assessed | ||

M0 No distant metastasis | ||

M1 Distant metastasis | ||

M1a Non-regional lymph node(s) or lung | ||

M1b Other sites | ||

S: serum tumor markers | ||

Sx Serum marker studies not available or not performed | ||

S0 Serum marker study levels within normal limits | ||

LDH (U/L) | hCG (mIU/mL) | AFP (ng/mL) |

S1 < 1.5 × N and | <5,000 and | <1,000 |

S2 1.5– 10 × N or | 5,000–50,000 or | 1,000–10,000 |

S3 > 10 × N or | >50,000 or | >10,000 |

N indicates the upper limit of normal for the LDH assay | ||

Levels should be evaluated before and after orchidectomy and during routine follow-up to monitor therapeutic response. Tumor marker levels should be interpreted with caution. Metastatic disease cannot be excluded on the basis of normal marker levels, and persistently elevated levels post-orchidectomy does not always signify metastatic disease since liver dysfunction and hypogonadotropism can also cause raised levels. However, as for all tumor markers, potential uses of serum tumor markers for GCTs may include screening, diagnosis, monitoring during treatment and surveillance after therapy is completed [18].

Alpha fetoprotein (AFP): AFP is a 69,000-kD single chain polypeptide which is similar in size and structure to human serum albumin. As a tumor marker, AFP is useful in detecting germ cell tumors of the ovary and testis, primary hepatocellular carcinoma in adults and hepatoblastoma in children. AFP is not specific for these cancers. In germ cell tumors AFP is secreted by embryonal cell carcinoma and yolk sac tumor but not by pure choriocarcinoma or pure seminoma. Yolk sac tumors appear to be the primary source of AFP with more than 90 % of tumors reacting positively to anti-AFP antibody, and in those tumors not demonstrating reactivity to anti-AFP antibody, serum levels are not elevated.

Beta human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG): Primary production of hCG occurs during pregnancy by the syncytiotrophoblastic cells of the placenta, which maintains the corpus luteum. In GCT, syncytiotrophoblastic cells are responsible for the production of hCG. All patients with choriocarcinoma and 40–60 % of patients with embryonal cell carcinoma have elevated serum levels of hCG. Approximately 10–20 % of patients with pure seminoma have elevated serum hCG, though the level is typically below 500 mIU/m. The serum half-life of hCG is between 24 and 36 h.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH): GCT patients typically express high levels of LDH isoenzyme 1 (LDH-1) [19]. Dying and dead cells leak LDH, which can be measured in the serum. LDH is a less-specific marker for GCTs, but levels can correlate with overall tumor burden

Placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP): PLAP is a fetal isoenzyme that is frequently elevated in patients with seminoma (60 –70 %), but due to its low specificity, it is not routinely used in the management of GCT.

To sum up, AFP is higher than normal in up to 65 % of patients with NSGCT, but it is never raised in those with pure seminomatous tumors. The hCG level is raised in up to 60 % of patients with advanced nonseminomatous GCT and in 15–20 % of those with seminoma. The LDH level is raised in most patients with advanced nonseminomatous GCT and seminoma [20].

49.2.3 Risk Factors

While the distinct causes of testicular cancer are not clear, several risk factors could be identified from anamnesis data: maldescensus testis, family history, previous testicular cancer, infertility, intersexual disorders and carcinoma in situ.

Familial testis cancer: About 2 % of testicular cancer cases have another family member who is also affected with the disease. The relative risk is respectively eight- to tenfold for brothers and four- to sixfold for fathers and sons [7, 21].

Genetics or bilateral cancer: The development of a GCT confers an elevated risk of developing a second primary cancer in the contralateral testis either at the same time or at a later date [9, 10, 22].

Cryptorchidism: The normal testis descends through the inguinal canal into the scrotum at 36 weeks of gestation and is guided by the gubernaculum testis, which arises from the inferior pole of the testis and is attached to the scrotum. Inguinal canal is the most common location for the undescended testis, although it may be present anywhere along the normal path of descent. Undescended testis has increased risk of malignancy, typically seminoma [5, 23].

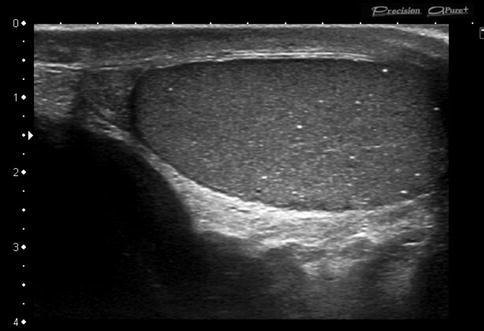

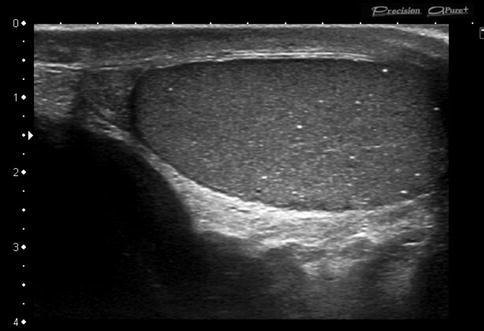

Testicular microlithiasis (TM): TM is present in about 5 % of the male population between 17 and 35 years of age. TM is identified on ultrasonographs as multiple, diffuse, small 1- to 3-mm echogenic foci without acoustic shadowing within the testicular parenchyma (Fig. 49.1). Presence of five or more calcifications per transducer field is considered abnormal. Testicular microlithiasis is commonly associated with testicular abnormalities, such as infertility, cryptorchidism and neoplasms (especially seminoma). Although microcalcifications exist in roughly 50 % of GCTs, most men with testicular microlithiasis do not develop testicular cancer. Ultrasound surveillance is unlikely to benefit patients with testicular microlithiasis in the absence of other risk factors [5]. In the presence of additional risk factors (previous testicular cancer, a history of maldescent or testicular atrophy), patients are likely to be under surveillance; nonetheless, monthly self-examination should be encouraged, and open access to ultrasound and formal annual surveillance should be offered [24–26].

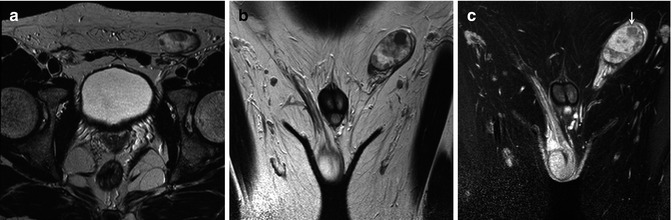

Fig. 49.1

Testicular microlithiasis. Longitudinal greyscale sonogram shows multiple (>5) punctate echogenic foci without acoustic shadowing

49.2.4 Imaging Examination

49.2.4.1 T Staging

The clinical stage determined at diagnosis depends on the accuracy of the imaging technique used. In most cases the testicle is the primary site, although tumors can also be originated in the retroperitoneum and the mediastinum. TNM staging classification of testicular tumors (Table 49.2) is recommended by the guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the European Germ Cell Cancer Consensus Group [27].

Ultrasound (US)

US is the primary imaging technique for the evaluation of scrotal contents, and it is used to confirm the diagnosis, to distinguish from other scrotal abnormalities and to exclude disease in the contralateral testis [28, 29]. The homogeneous echotexture of the normal testicular tissue represents an excellent background for the detection of intratesticular lesions. Small tumors are displayed as focal lesions, and larger tumors may destroy the entire testicular structure. As general rule, most solid intratesticular masses should be considered malignant (malignancy rate of 90–95 %); contrary extratesticular masses are more likely to be benign (malignancy rate of 16 %) [30]. Malignant testicular tumors are predominantly hypoechogenic (92 %), but they may also be displayed as hyper- or mixed echogenic lesions (Fig. 49.2); however, benign diseases such as infarct, which can be seen as a triangular-shaped avascular lesion, or focal orchitis may have a similar appearance [31]. Duplex and colour flow Doppler may be used to detect intratumoral vascularity, which depends more on tumor size than histology (Fig. 49.2). In a study of 28 patients with surgically proven testicular tumors, 95 % of tumors greater than 1.6 cm demonstrated increased vascularity, whereas histology showed no correlation with vascularity [32]. Colour Doppler may be useful in the paediatric population, in whom tumors may be subtle by greyscale US but tend to be hypervascular by colour Doppler imaging. Unfortunately, US findings are not specific for each tumor type, although several clinical and radiological features may be useful and will be described in the following paragraphs (Table 49.3).

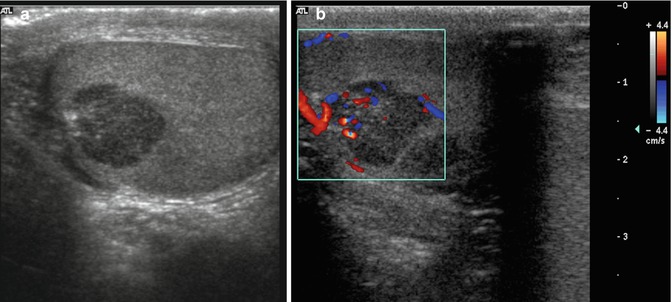

Fig. 49.2

Mixed germ cell tumor of testis. Greyscale sonogram (a) and corresponding colour flow Doppler (b) demonstrate a hypoechoic lesion with increased vascularity

Table 49.3

Clinical and radiological findings of different scrotal tumors

Seminoma | NSGCTs | Leydig | Sertoli | Lymphoma | Metastases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ultrasonography | Lobulated Homogeneous Well defined Rarely involves both the testis and epididymis. Multinodular: continuity nodules | Heterogeneous Embryonal carcinoma: invasion of tunica and extension into the epididymis. No enlargement of scrotum Teratomas: cystic spaces, multiculated Choriocarcinoma: haemorrhagic and small | Nonspecific Small Cystic areas, haemorrhage or necrosis | Small Well defined Variable appearance Increased echogenicity reflecting dense collagenous matrix Multicystic “spoke wheel” | Infiltration + enlargement of the testis Hypoechoic Extends outside the testis often into the epididymis Bilateral in up to 20 % of cases | Nonspecific Hypoechoic but may be complex and even echogenic Differentiating other primary testicular tumors is difficult |

Calcification | Testicular microlithiasis | Scarring Calcifications Ossificating (30 %) Burned-out tumors: area of calcification | No | Prominent calcifications 20 % bilateral if calcifying Sertoli cells | No | Unknown |

Doppler | Increased | Increased | Peripheral and circumferential blood flow and lack of internal vascularity | Increased | Increased | Increased |

MRI | Hypointense on T2 Uniform signal Fibrous septa: greater enhancement than the rest of the tumoral tissue | Heterogeneous signal Necrosis or haemorrhage Heterogeneous enhancement | Isointense on T1 Hypointense on T2 Homogeneous enhancement | Nonspecific Variable | Hypointense tissue on T1 and T2 Mild enhancement on postcontrast images (less than the normal testicular parenchyma) | Hypointense on T2 Enhancement after gadolinium Multifocal lesions Bilateral 15 % |

Markers | AFP (−) Pure seminoma (+) Mixed seminoma LDH (advanced disease) | BHCG (+) AFP (+) LDH (advanced disease) | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative PLAP negativity |

Associated entities | Cryptorchidism | No | Klinefelter syndrome | Peutz–Jeghers syndrome Carney complex | No | Known primary malignancy Coexisting with other metastases |

Clinically | Painless palpable mass | Painless palpable mass | Secretion of androgens or estrogens: Gynaecomastia Precocious puberty Decreased libido | Unusual hormonal production | Painful testicular swelling or systemic symptoms such as weight loss, night sweats, anorexia, fever and weakness | Seen in the setting of widespread disease and are rarely the presenting complaint Growing testicular mass if metastasis of renal cell carcinoma |

Tumor Types

Germ Cell Tumors (GCTs)

GCTs represent 95 % of intratesticular malignancy, with both subtypes (seminoma and NSGCTs) having similar percentages. NSGCTs include embryonal cell carcinoma, yolk sac tumor, teratoma, choriocarcinoma and mixed subtypes (the most common subtype). NSGCTs more often show a heterogeneous appearance due to internal haemorrhage, cystic changes and calcification with irregular or ill-defined margin [29, 33]. NSGCTs are more aggressive, invading the tunica albuginea and frequently with metastases at the time of discovery.

Seminoma: Seminoma is the most common pure GCTs. Approximately 15 % of patients who have seminoma have a history of cryptorchidism [5] (Fig. 49.3). Seminomas are also commonly found in patients who have TM [33]. Ultrasound images of seminoma typically show a lobulated, well-defined homogeneously hypoechoic lesion with increased vascularity. Seminomas can be lobulated or multinodular, although nodules are most commonly in continuity with one another. Approximately 10 % of seminomas showed small cystic areas corresponding to the dilated rete testis caused by tumor [31].

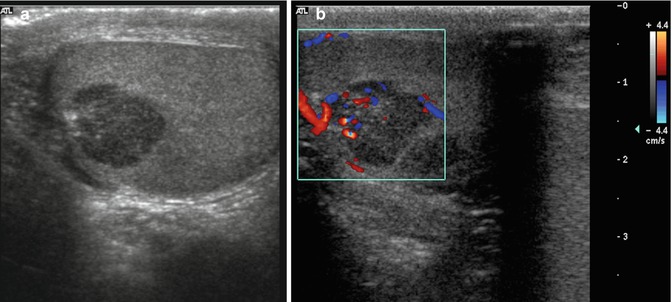

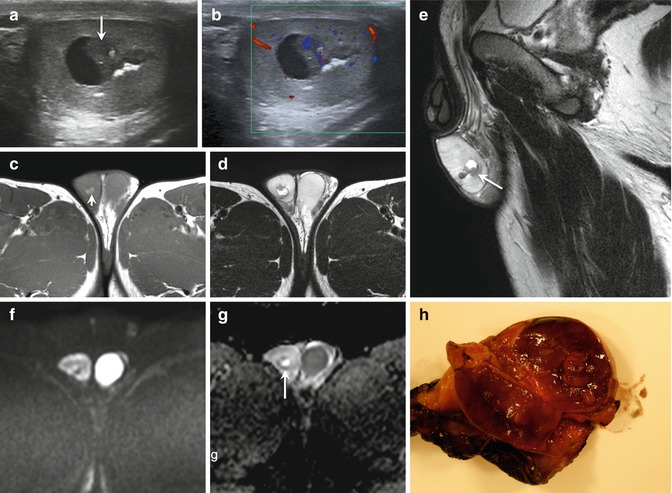

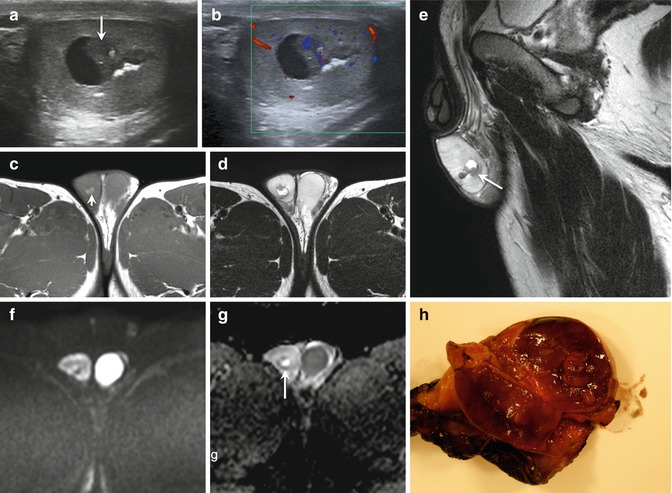

Fig. 49.3

A 43-year-old man with seminoma in an undescended testis. Axial (a) and coronal (b) T2-weighted images depict right testicular mass with low signal intensity. Coronal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image (c) shows areas without enhancement (arrow) corresponding to necrosis found at pathological examination

Embryonal carcinoma: Embryonal carcinoma occurs in a younger population than seminoma, usually between 25 and 35 years. On US examination, these tumors are predominantly hypoechoic with poorly defined margins and a heterogeneous echotexture. They do not cause enlargement of the scrotum. Unlike the seminoma, invasion of the tunica albuginea and extension into the epididymis can occur in approximately 20 % of cases [16].

Yolk sac tumor: Yolk sac tumor accounts for 80 % of childhood’s testicular neoplasms, with most cases occurring before the age of 2 years. Their ultrasound features are nonspecific and usually heterogeneous [29].

Teratoma: Teratoma is the second most common testicular neoplasm in children, occurring in boys less than 4 years of age. They are classified as mature or immature forms. Pure testicular teratoma is more commonly found in very young children (<2 years of age), whereas teratomas in the context of mixed germ cell tumors are more common in young adults (typically 20–30 years of age). Teratomas generally form well-circumscribed and very large complex masses. Cystic components are more common than other NSGCTs and may appear anechoic or complex depending on the cyst contents [34].

Choriocarcinoma: Choriocarcinoma is a rare germ cell tumor. In its pure form, it is seen in less than 1 % of patients, but it occurs in mixed germ cell tumors in 16 % of cases. Choriocarcinoma has the worst prognosis of any GCT, with death usually occurring within 1 year of diagnosis. The primary tumor and metastases are often haemorrhagic [35].

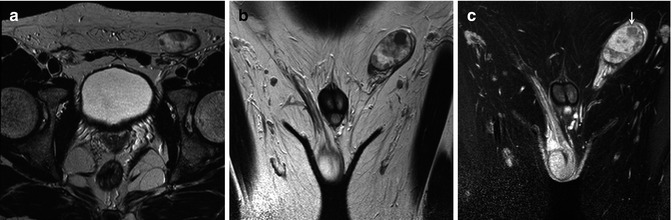

Mixed germ cell tumors: These tumors contain more than one germ cell component. They constitute about 40–60 % of all germ cell tumors. Any combination of cell types can occur. Embryonal carcinoma is the most common component and is often combined with one or more components of teratoma, seminoma and yolk sac tumor, with teratoma and embryonal carcinoma (teratocarcinoma) being the most frequent combination. The imaging findings are variable depending on the dominant component (Fig. 49.4) [34].

Fig. 49.4

22-year-old man with right mixed cell tumor containing 90% embrional carcinoma. US of testis (a) reveal a heterogeneous mass with some necrotic areas (short arrow), calcium and solid areas (large arrow).Necrotic area is visible on MRI as hyperintense signal on T1 (arrow in c) and axial (d) and sagittal (e) T2- weighted images with no restricted DWI (f). Axial ADC map (g) show a high ADC value(2.5 x 10-3 mm2/ s). Solid areas show marked vascularity on color flow Doppler (b), hypointense signal on T1 and T2-weighted images(arrow in figure e) and restricted DWI with low ADC value (0.588 x 10-3 mm2/ s) (arrow in g). Macroscopic view (h) of testicle after orchiectomy confirms imaging findings

Regressed germ cell (burned-out) tumors: Burned-out germ cell tumor refers to the presence of a metastatic germ cell tumor with histological regression of the primary testicular lesion. These tumors are clinically occult, with the testis being normal to small upon palpation; therefore, US plays a vital role in the search for the primary regressed tumor. They are generally small and can be hypoechoic, hyperechoic or merely an area of focal calcification. Histological evaluation reveals presence of fibrosis and scar tissue with no tumors cells.

Stromal Tumors

Leydig cell tumors (LCTs): LCTs are rare accounting for 1–3 % of all testicular neoplasms. These tumors are most common in prepubertal boys aged 5–10 years and in adults aged 30–60 years [36]. They are usually benign, but approximately 10 % of LCTs are malignant, and this variant occurs exclusively in adults [37, 38]. These tumors are often hormonally active, leading to feminising or virilising syndromes. Most LCTs are sonographically visualised as smoothly demarcated, intratesticular masses with an echo-poor and homogeneous appearance. Imaging features are largely nonspecific to distinguish Leydig cell tumors from malignant germ cell tumors. The tentative diagnosis of an LCT can be made only in the presence of gynaecomastia. If this diagnosis is favoured before surgery (because of the clinical presentation), tumor enucleation can be performed.

Sertoli cell tumors (SCTs): SCTs are rare and account for less than 1 % of testicular tumors. They are most common in younger patients (<40 years) and are mostly benign, although malignant subtypes exist. The most common clinical presentation is a painless slow-growing tumor [39]. It is unusual to have sufficient hormonal production to induce clinically apparent endocrinologic changes. Tumor markers are usually negative.

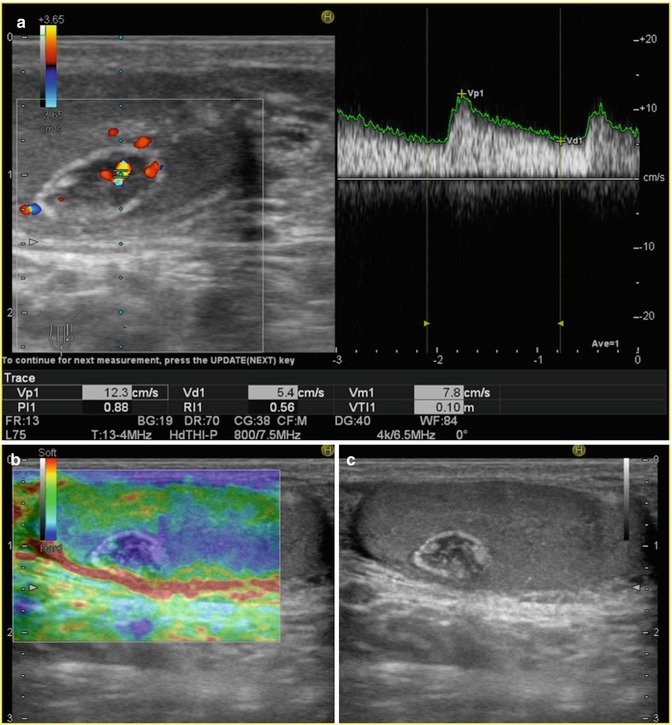

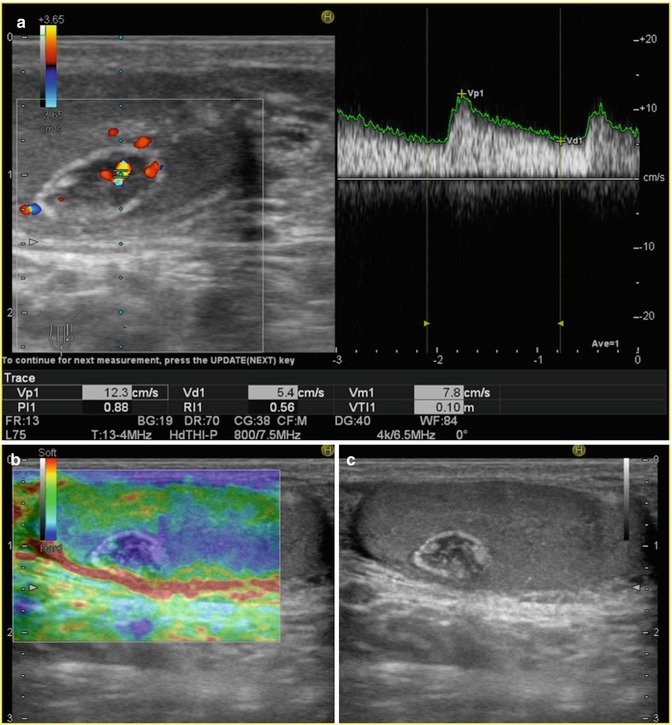

These tumors are small, well defined, homogeneous and hypoechoic; however, large-cell calcifying SCT (Fig. 49.5) is a distinct subtype of Sertoli cell tumor with unusual features including bilaterality and multifocality, which may occur in isolation or associated with acromegaly, hypercortisolemia and genetic abnormalities including Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, tuberous sclerosis and Carney’s complex. Ultrasound does not usually provide key data.

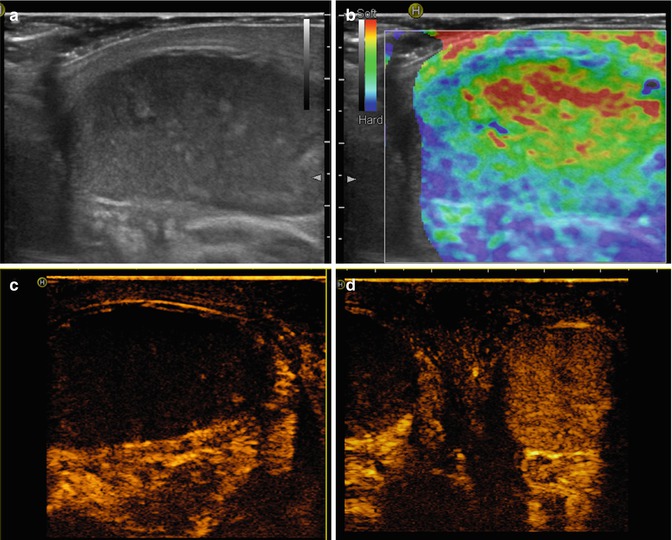

Fig. 49.5

Calcifying Sertoli cell tumor. Colour flow Doppler sonograms (a) demonstrate a well-defined mass with internal increased vascularity. Image from RTE (b) shows a hard lesion (blue), and corresponding longitudinal greyscale US (c) scan shows a hypoechoic well-defined mass with peripheral and internal calcifications (Courtesy of Gabriel Fernández, MD. HNSS, Ávila, Spain)

Other Testicular Tumors

The involvement of testis parenchyma for non-primary testicular malignancies comprises about 5 % of intratesticular malignancy. The most common include lymphoma, leukaemia and metastases.

Testicular lymphoma (TL) is the most common testicular malignancy in men older than 60 years. TL is a rare extranodal subtype of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma that usually corresponds to large B-cell lymphomas [40]. TL may be the primary and only manifestation of malignant lymphoma, the initial sign of generalised disease, or may occur during the clinical course of a patient with established lymphoma. Secondary involvement of the testis in patients with lymphoma is far more common than primary TL [41]. Lymphoma is locally aggressive and can typically infiltrate the epididymis, spermatic cord or scrotal skin. Sonographic exam usually evidences a focal or diffusely infiltrative homogeneous hypoechoic mass that maintains the normal ovoid testicular shape. Duplex and CFD demonstrate hypervascularity, regardless of tumor size [42]. TL shows a tendency to spread to several extranodal sites at presentation or relapse [41].

Primary leukaemia of the testis is rare. However, the testis is a common site of leukaemia recurrence in children. The blood–testis barrier prevents the accumulation of chemotherapeutic drugs within the testes allowing leukaemic cells to be “hidden” during treatment. Sonographic features of leukaemia of the testis do not show a specific pattern. Colour Doppler is helpful to demonstrate leukaemic infiltration due to increased vascularity [35].

Although uncommon, metastases should be considered when multifocal extratesticular lesions are seen, particularly in the setting of a known primary malignancy. Metastases to the testis are mainly originated from the prostate (35 %), lung (19 %) and malignant melanoma or colorectal cancer (9 %). In children, most common sources include neuroblastoma, Wilms tumor and rhabdomyosarcoma [35]. Their sonographic appearance is nonspecific, and they are difficult to differentiate from other primary testicular tumors.

Radiologists play a pivotal role in characterising scrotal lesions for reaching the correct diagnosis. However, given the variety of imaging features on US, the diagnosis of a testicular tumor cannot be made solely on the basis of the sonographic appearance. New US-based techniques such as DCE-US or elastography may demonstrate functional and structural features of tumors.

Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography (CEUS)

CEUS is particularly useful in detection and characterisation of tumor lesions in different areas [42]. However, there is only a limited experience of CEUS of the testicles. Recently, some articles reported the potential usefulness of CEUS for the evaluation of acute scrotal pain and testicular masses. CEUS is able to depict parenchymal disorders on the basis of vascularity, helping in the differential diagnosis of scrotal lesions and traumatic changes (Fig. 49.6). Valentino et al. evaluated the efficacy of CEUS in patients with acute scrotal pain not defined at ultrasound with colour Doppler [43]. They concluded that CEUS was more accurate in the final diagnosis compared to US and proposed the use of this technique in emergency cases where US diagnosis remains inconclusive. Look et al. demonstrated the feasibility of CEUS in the diagnosis of testicular masses [44]. Their results showed that hypervascularisation is an important feature in the diagnosis of malignancy. Therefore, CEUS may be particularly valuable in the assessment of small intratesticular lesions, in which colour Doppler flow has limited value.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

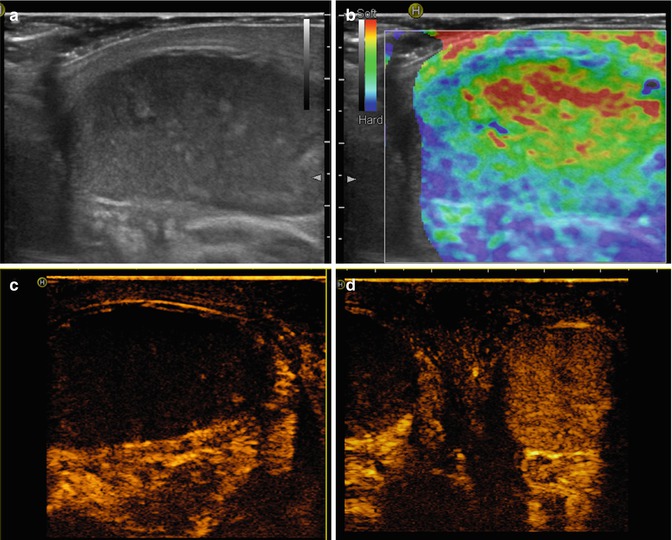

Fig. 49.6

Testicular torsion. Longitudinal greyscale sonogram (a) reveals a heterogeneous echotexture with hyperechoic regions that represents haemorrhage. Image from RTE (b

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree