Shoulder 1

Supraspinatus Tendon

Introduction

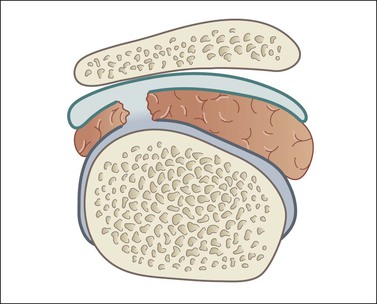

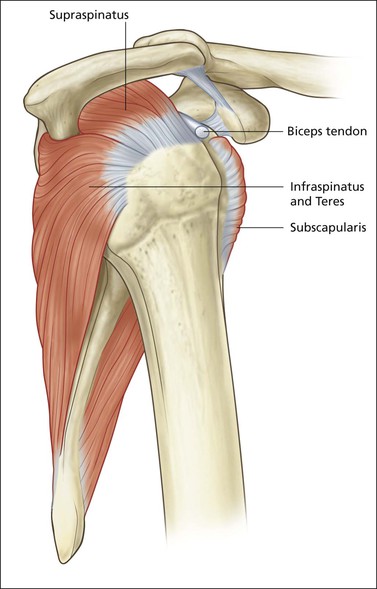

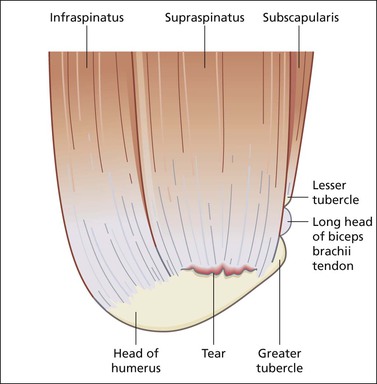

Shoulder pain is one of the commonest orthopaedic presentations in the general population and subacromial impingement is a common underlying cause. The glenohumeral joint is an intrinsically unstable joint and the tendons of the rotator cuff play an important role in stabilizing it (Fig. 2.1). The supraspinatus tendon (SST), the most important component of the rotator cuff, lies along the superior aspect of the humeral head passing beneath the coracoacromial arch. The arch is made up of a bony component posteriorly, the acromion, and a soft tissue component anteriorly, the coracoacromial ligament. The other tendons of the rotator cuff are subscapularis, anteriorly, and infraspinatus and teres minor, posteriorly.

Figure 2.1 Sagittal diagram of rotator cuff tendons. The tendons of subscapularis, supraspinatus and infraspinatus merge together to form the cuff. There is an anterior opening to allow egress of the long head of biceps. This is called the anterior interval.

The principal pathology is SASD bursitis with or without supraspinatus tendinopathy or tear.

The Aetiology of Shoulder Impingement

Bony Impingement

Multiple factors have been implicated in the aetiology of impingement and rotator cuff disease. Attention is frequently drawn to the shape of the acromion, although it is now generally accepted that, apart from extremes, changes in the acromion are secondary to impingement rather than a primary cause. Bony irregularity on the undersurface of the acromion can arise as a result of enthesopathy at the coracoacromial ligament attachment. In extreme cases, a distinct bony spur may be present, leading to further narrowing of the subacromial space. Entheseal changes may also occur at the humeral insertion of the involved tendons. Bony upgrowth from the humeral head combines with bony downgrowth from the acromion leading to further diminution in the subacromial space, increased bursal impingement and progressive supraspinatus tendinopathy (Fig. 2.2). Although bony and entheseal factors have been shown to narrow the subacromial space, it is probable that they are not the most important.

Figure 2.2 A down sloping acromion and/or a spur/enthesopathy on the undersurface of the acromion may impinge on the bursal space. In addition, bony enthesopathy may impinge on the undersurface of the SST. An important factor is shoulder dyskinesia, where scapular rotation and upward migration of the humeral head further impinge on the subacromial space.

SICK Scapula

Scapulothoracic dyskinesia refers to the narrowing of the subacromial space that arises as a result of abnormal scapular motion. The term SICK scapula syndrome comprises: Scapular malposition, Inferomedial prominence, Coracoid pain and scapular dysKinesis. The muscular imbalance between the thoracic and cuff musculature leads to elevation of the humeral head and impingement of the subacromial space beneath the coracoacromial arch. Abnormal shoulder biomechanics, termed microinstability, with or without joint laxity, may also contribute. The aetiology of the SICK scapula is incompletely understood, but maladaptive postural biomechanics, possibly due to habitual poor posture or other causes, leads to the abnormal relationship between the scapula, thorax and humerus. The contribution that scapular dyskinesia makes to impingement is important and underlines the importance of physical therapy as part of the patient’s management.

Supraspinatus Tear Nomenclature

Partial Versus Full Thickness

The thickness of a tear is described as partial or full; the width of a tear is described either by its dimensions (anterior/posterior × medial/lateral) or by how much intact tendon tissue remains (standard descriptive terms are described below).

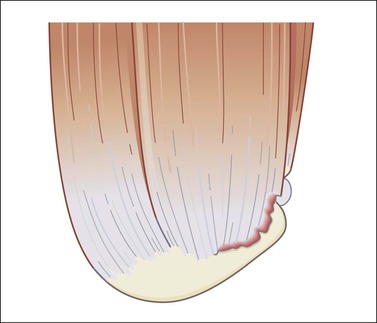

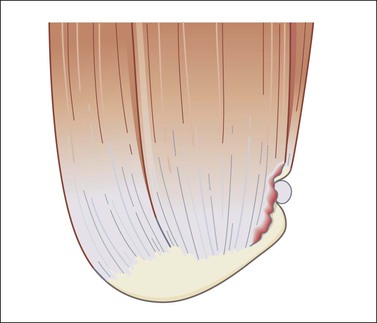

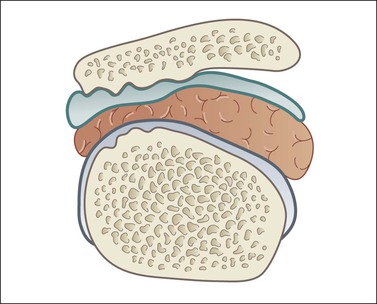

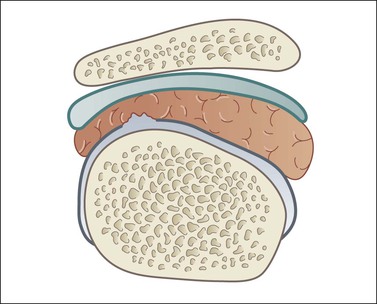

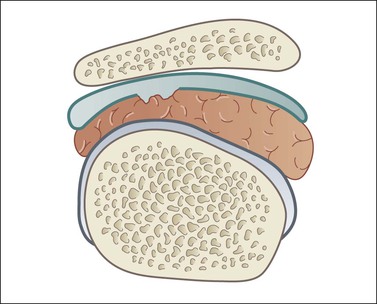

A partial thickness tear is one that involves either the joint or bursal surface alone and does not allow communication between the two compartments (Figs 2.3 to 2.5). If contrast is injected into the glenohumeral joint, it will fill a joint surface partial tear but will not pass into the SASD bursa. If contrast is injected into the bursa, it will fill a bursal surface partial tear but will not pass into the joint. The most common tear pattern is said to be a joint surface partial tear, although some authors say that this is due to underdiagnosis of bursal surface lesions. A full-thickness tear is present when both surfaces are involved and the tear results in communication between the joint and the bursal compartments. Once this communication is present, a full-thickness tear is diagnosed regardless of the width of the communicating channel. Some full-thickness tears are of large width, measuring greater than 3 cm in diameter, others are little more than pinholes. A full-thickness tear might also be described as extending from the anterior leading edge with 1 cm of supraspinatus remaining intact or as involving the midportion with 1 cm of supraspinatus intact anteriorly and 1 cm of infraspinatus intact posteriorly, and so forth.

Figure 2.3 Schematic diagram of joint surface partial tear. There is no communication between the joint space and the SASD bursa.

Figure 2.4 Schematic diagram of a bursal surface partial tear. There is no communication between the joint and SASD bursal spaces.

Full-Thickness Tear Patterns, Location and Shape

Tears are occasionally further divided according to their shape, although this tends to be used more arthroscopically than with imaging. The simplest shape is linear. This is a separation from the humeral attachment, perpendicular to the normal direction of supraspinatus fibres. Linear tears may involve the anterior edge or midsubstance (Figs 2.6 and 2.7). On ultrasound, these are much larger in one plane than the other. Extension in two tendon planes leads to the formation of L-shaped or tongue shaped tears (Figs 2.8 and 2.9). When retraction occurs, the tears are described as V or U shaped (Fig. 2.10).

Figure 2.6 Schematic diagram of a linear supraspinatus tear involving the midportion/crescent/footprint. Difficult to see on axial images.