Etiology

Silicosis and coal workers’ pneumoconiosis (CWP) are occupational lung diseases; silicosis is caused by continued exposure to excessive amounts of respirable silica, and CWP is caused by exposure to carbonaceous material (anthracosis). Respirable crystalline silicate and coal dust embed in the lungs, causing granulomatous and fibrotic changes that lead to radiographic and pathologic abnormalities. Silica is a naturally occurring mineral that is mainly composed of silicon dioxide (SiO 2 ). It exists in two forms: crystalline silica, which causes silicosis, and amorphous silica, which is not toxic. The three most common forms of crystalline silica are quartz, cristobalite, and tridymite, but quartz is the most common form of inhaled silica.

The diagnosis of silicosis and CWP is based on the typical radiographic appearance of diffuse nodules or reticulonodular pattern in the presence of a strong occupational exposure to silica and coal dust. The guidelines for the use of the ILO (International Labour Organization) International Classification of Radiographs of Pneumoconiosis were recently updated in 2011 to include criteria for the interpretation of digital images and is the most widely accepted classification of the extent of involvement of the pneumoconioses and one in which the presence or absence of pneumoconiosis is established in workers exposed to mineral dust, including silica. The ILO system uses a step-by-step method to evaluate chest radiographs, which are compared with standard reference film-screen or digital radiographs available from the ILO, with standard nomenclature to describe the shape, size, location, and abundance of opacities.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Workers engaged in occupations such as tunneling, mining, sandblasting, and quarrying are inevitably exposed to silica owing to its ubiquity in the earth’s crust. Other workers engaged in occupations that predispose to silica exposure include jade polishers, foundry and pottery workers, glass and silica brick workers, goldworking jewelers, and electric cable manufacturers. More newly recognized causes of silica exposure, resulting in accelerated silicosis and silicoproteinosis, include sandblasting in denim clothing and manufacturing engineered stone countertops containing quartz. Environmental silica arises as a result of crystalline silica becoming airborne in arid, windy conditions or during agricultural, urban, or construction activities. Inhalation of environmental silica and mixed dust has led to lung fibrosis.

Hnizdo and Sluis-Cremer showed the relationship between exposure to silica and silicosis. The cumulative exposure for the entire cohort in their study was about 2 mg/m 3 per year over an average exposure period of 25 years. No silicosis occurred when the cumulative exposures were less than 0.9 mg/m 3 per year. In contrast, the cumulative risk of silicosis was approximately 25% at a cumulative exposure of 2.7 mg/m 3 per year and 77% at the highest observed cumulative exposure level of 4.5 mg/m 3 per year. This dose-response relationship between the duration of exposure to the quartz-containing dust and the prevalence of silicosis also has been observed by other investigators. The effects of smoking on the prevalence of silicosis were illustrated in a cross-sectional survey of 3258 workers in a Dutch fine-ceramic industry, in which the prevalence of silicosis among heavy smokers with 20 years’ or more exposure to quartz-containing dust was 50% higher than in light smokers and nonsmokers.

The prevalence and incidence of silicosis worldwide are difficult to determine because of variable industrial practices and work safety standards. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health estimated that in 1983 approximately 2.3 million workers at 238,000 work sites were exposed to silica dust. It was more recently estimated that 59,000 workers may be at risk of developing some degree of silicosis, with 250 deaths per year being attributed to silica exposure. Approximately 1500 cases of silicosis are diagnosed annually in the United States; silicosis was cited as the primary or contributing cause of death in 13,744 deaths between 1968 and 1990 in the United States. There has been a trend of decreasing annual death rates correlating with a decreased incidence since a peak during World War II. Specifically, deaths decreased from 1157 in 1968 to 301 in 1988 in the United States, although the prevalence rates in developing nations remain significantly higher. In Colombia and India, respectively, 1.8 million and 1.69 million workers are estimated to be exposed to and at risk of developing silicosis. Workers in India who are involved in quarrying shale sedimentary rocks have a 55% prevalence rate of silicosis, whereas 50% of Latin American miners older than 55 years develop silicosis. A study in Northern Thailand of 266 mortar and pestle workers documented a 21.1% prevalence rate for silicosis. In a separate study involving workers from 33 stone-grinding factories in Thailand, 31 of the factories (93.6%) were found to have levels of total or respirable dust exceeding acceptable levels. The prevalence of silicosis was 9%.

CWP occurs after exposure to coal dust for longer than 20 years on average, but some cases have been reported with less than 10 years of exposure. The severity and prevalence of CWP are related to the duration of exposure, the amount of coal dust inhaled, and the carbon content (rank) of the coal dust. Higher concentrations of coal dust exposure are associated with higher prevalence of CWP. Similarly, a high rank of coal dust, such as anthracite, increases the risk of CWP. The prevalence of CWP varies from country to country, within different regions of a country, and from mine to mine. The overall prevalence of CWP in the United States was reported to be 30% in an interagency study in the 1960s. Although this percentage may be decreased in more recent years as a result of federal legislation that mandated substantially lower dust levels in coal mines, some recent studies have demonstrated areas of increased prevalence of progressive massive fibrosis (PMF) among underground U.S. coal miners despite exposure after implementation of those federal dust regulations. Currently, it is estimated that 2% to 12% of U.S. coal miners develop category 2 or greater disease after a 40-year working life, with an estimated prevalence of PMF of 1% to 7%. In comparison, the predicted prevalences for CWP and PMF in British coal miners are 9% and 0.7%, respectively.

Clinical Presentation

Silicosis

The three main clinical presentations of silicosis are acute silicosis (silicoproteinosis), accelerated silicosis, and classic silicosis, and they are determined primarily by the intensity and the length of exposure to silica. Silicoproteinosis (acute silicosis) is an acute and progressive form of silicosis that often results in death from respiratory failure. This variant of silicosis can develop within a few weeks or months of exposure to very high concentrations of silica and is associated with occupations such as sandblasting, surface drilling, tunneling, silica flour milling, and quartzite milling. The lungs show a ground-glass appearance similar to that of pulmonary edema and alveolar proteinosis. The lesion may consolidate into appearances more characteristic of PMF over a short time. Workers usually present with rapidly progressive dyspnea, cough, and weight loss and develop cyanosis and respiratory failure. Death usually occurs within a short time despite intensive treatment. It has been proposed that acute silicosis occurs in workers exposed to freshly fractured silica dust and that surface Si* and SiO* radicals generated during fracturing play an important role in the rapid onset of this variant of silicosis.

With accelerated silicosis, the exposure time after which the disease becomes clinically evident is much shorter than classic silicosis, ranging from 5 to 10 years of exposure, with the rate of disease progression noticeably faster. The symptom of breathlessness occurs 1 year after exposure, with the patient’s condition rapidly deteriorating to hypoxic respiratory failure and death within 5 years. High concentrations of dust in a relatively confined space are thought to predispose an individual to this form of silicosis, which is common in certain occupations, such as sandblasting, stone masonry, and other crushing operations. Except for this aggressive time course, the radiographic, clinical, and pathologic features of this entity are nearly indistinguishable from classic silicosis.

Long-term exposure to low concentrations of silica is associated with a slow progressive nodular infiltration in both lungs, predominantly in the upper lung zones. Classic silicosis is the most common presentation whereby patients remain asymptomatic until after 10 to 20 years of continuous silica exposure, by which time radiographic abnormalities are evident. In contrast to other inhalational occupational lung diseases, lung changes in silicosis often progress even after the individual has been removed from the causative environment. Although most patients are asymptomatic initially, dyspnea on exertion and then at rest is common. A relationship between severity of dyspnea and radiographic abnormalities has been documented. The lung lesions are usually progressive and may result in PMF. PMF is the result of the coalescence and agglomeration of several smaller nodules together with increased profusion and enlargement of nodules. According to the Silicosis and Silicate Disease Committee, a PMF lesion is defined as a lesion greater than 2 cm in diameter, in contrast to the 1 cm or larger radiographic size established by the ILO. Cavitation and extensive destruction of the lung parenchyma, including bronchioles and blood vessels, are common in PMF and may signify superimposed infection from anaerobic bacteria or tuberculosis.

With progressive lung damage, pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure eventually supervene. Emphysema is common in silicosis and has been considered the major cause of cor pulmonale and disability by some investigators. Additionally, risk of other cardiovascular diseases is increased, including stroke, peripheral vascular disease, and congestive heart failure. Pneumothorax can complicate silicosis and occurs more frequently among patients with accelerated or acute silicosis. Other conditions that may complicate silicosis include Caplan syndrome, tuberculosis, carcinoma, and connective tissue disease. The two most serious complications, lung cancer and tuberculosis, may affect the prognosis and natural history of the underlying disease. Chronic silica inhalation is associated with a threefold increased risk of mycobacterial infections (silicotuberculosis). The risk increases with more severe disease in terms of nodular profusion and PMF ; this predisposition depends on the prevalence of tuberculosis in the population from which the workers originate.

Rheumatoid pneumoconiosis (Caplan syndrome) was initially identified in CWP but is now known to occur in silicosis as well, although rarely. The incidence of this disease ranges from 0.48% to 0.74% and is characterized by rapidly developing large opacities (1–5 cm) located mostly in the periphery of the lungs, often with only mild silicosis.

The association between silicosis and lung cancer has been documented in several studies and recognized as an occupational carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer since 1996. The risk is greatest for workers with established silicosis.

The strength of the association between silicosis and connective tissue disease varies with the type of connective tissue disorder. The risk of developing systemic sclerosis particularly in workers with high exposure to silica dust is well established, although such causal associations between silicosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus are less widely reported.

Coal Workers’ Pneumoconiosis

Inhalation of coal mine dust can lead to the development of several disease entities, including CWP, bronchitis, emphysema, Caplan syndrome, and silicosis. The two most common patterns of disease found in coal miners are simple CWP and complicated CWP. With increasing duration of coal dust exposure, CWP may progress to complicated CWP, in which the nodules coalesce to form black, rubbery parenchymal masses usually in the upper posterior lungs, resulting in PMF. Progression from simple CWP to PMF has been related to radiographic severity of disease, coal mine dust–exposure level, and total dust burden, with the average transition from simple CWP to complicated CWP occurring over 12.2 years.

CWP is usually asymptomatic, and most chronic pulmonary symptoms in coal miners are attributed to other lung conditions, such as industrial bronchitis from coal dust or coincident emphysema from smoking. The main symptom even in nonsmokers is chronic cough, which persists even after patients leave the workplace. PMF causes progressive dyspnea with production of black sputum (melanoptysis) when the PMF lesion liquefies and ruptures into the airways. As with silicosis, PMF lesions often progress to pulmonary hypertension with right ventricular and respiratory failure.

An association between CWP and features of rheumatoid arthritis is well described. It is unclear whether CWP predisposes miners to developing rheumatoid arthritis, whether rheumatoid arthritis takes on a unique form in patients with CWP, or whether rheumatoid arthritis alters the response of miners to coal dust. Multiple rounded nodules in the lung appearing over a relatively short time (Caplan syndrome) represent an immunopathologic response related to rheumatoid diathesis. In contrast to lesions caused by PMF, which congregate in the upper lobes, these new lesions (known as Caplan lesions) tend to coalesce in the lung periphery. Histologically, the lesions resemble rheumatoid nodules, but they have a peripheral region of more acute inflammation.

As in silicosis, patients with CWP are at an increased risk of developing active tuberculous and nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Weak associations have been reported between CWP and progressive systemic sclerosis and stomach cancer. Cumulative dust exposure has been shown to have a significant relationship with increased mortality from cancers of the digestive system. It has been suggested that nitrosation of ingested coal dust in the acidic gastric environment could result in the production of carcinogenic products, which may lead to the higher incidence of gastric cancer in coal miners.

Silicosis in coal miners is usually found in conjunction with simple CWP and rarely as an isolated form of pneumoconiosis. It is difficult to distinguish between silicosis and CWP on chest radiography. The prevalence of silicosis in coal miners can be reliably determined only in autopsy studies. In the National Coal Workers’ Autopsy Study from 1972 to 1996, pathologic evaluations of 4115 autopsy cases found 23% of coal miners with pulmonary silicosis and 58% with lymph node silicosis.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

The pathogenesis of most pneumoconioses is a result of chronic inflammation that involves phagocytosis of the inhaled dust by alveolar and tissue macrophages and its deposition in the lung interstitium. Free particulate silica that is not ingested by macrophages enters the perivascular lymphatic channels to be translocated to the draining mediastinal lymph nodes as free particles or within macrophages. Inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1, also are released by damaged epithelial cells and macrophages. These inflammatory mediators destroy the lung parenchyma by attracting other inflammatory cells (macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes), resulting in alveolitis. In vivo and in vitro studies have shown that these silica-exposed macrophages release fibroblast growth factors that facilitate the accumulation of fibroblasts and fibroblast products, which induce inflammatory and fibrogenic reactions in the interstitium, alveoli, and lymph nodes. Various growth factors stimulate fibroblast and type II pneumocyte activity. Collagen and fibronectin production rapidly increase and eventually lead to fibrosis. Animal models have shown that even after the exposure to silica ceases, dust-laden macrophages continue to produce inflammatory mediators, such as interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α, propagating the inflammation-fibrosis cycle.

Silicoproteinosis

Silicoproteinosis is characterized by pulmonary edema, interstitial inflammation, and the presence of surfactant protein similar to that seen in alveolar proteinosis filling the alveolar spaces. The exudate in the alveoli is eosinophilic, with a fine granular appearance. Silicotic nodules are sparse and poorly demarcated, or absent, probably because they form shortly after exposure. Collagen deposition and fibrosis are rarely seen in silicoproteinosis.

Accelerated Silicosis

Accelerated silicosis is similar in many respects to acute silicosis, exhibiting an exudative alveolar lipoproteinosis associated with chronic inflammation. In addition, accelerated silicosis is associated with fibrotic granulomas containing collagen, reticulin, and numerous silica particles. The granulomas consist of numerous mononuclear cells, fibroblasts, and collagen fibers, with a predisposition for circular orientation showing the characteristics of immature silicotic nodules. The alveolar septa are lined with hypertrophic and hyperplastic alveolar type II epithelial cells with increased numbers of lamellar bodies.

Classic (Nodular) Silicosis

Nodular silicosis is characterized by the presence of small rounded nodules 3 to 6 mm in diameter. The nodules of silicosis are well defined and located in the perivascular and peribronchiolar interstitium and the paraseptal and subpleural interstitium, and they are preferentially distributed in the upper lobes. Adjacent vessels and bronchioles may become involved and destroyed by these nodules, with occlusion of their lumen. Hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes are enlarged and pigmented, similar to that found in the silicotic nodule. Calcification also is a frequent finding.

Progressive Massive Fibrosis

Conglomeration of the nodules frequently occurs to form large masses of PMF, usually in the upper lobes where nodular profusion is greatest. The lower lobes are less frequently involved. PMF lesions sometimes cross the interlobar fissure to form elongated masses from the lung apex to the lower lobe. PMF usually is associated with adjacent emphysema and composed histologically of hyalinized collagen without the concentric lamellar appearance found in silicotic nodules. Cavitation occurs as a consequence of infection by anaerobic organisms, ischemia, or tuberculosis. Although conglomeration usually occurs in a heavily dust-laden lung with a high profusion of nodules, its development does not always parallel nodular profusion.

Rheumatoid Pneumoconiosis

Nodules of rheumatoid pneumoconiosis are similar to necrobiotic nodules found in rheumatoid arthritis and can be classified as either classic or silicotic type. The former correspond to the original cases described by Caplan and are large nodules characterized by uniform necrosis and associated with little background pneumoconiotic nodules. The silicotic type consists of multiple smaller nodules, with the necrotic area retaining some characteristics of a silicotic nodule.

Mixed Dust Fibrosis

Although the radiographic characteristics of mixed dust fibrosis have not been a subject of interest in recent literature, this entity is frequently described in pathology textbooks and is of some clinical importance within the context of lung damage in exposed silica workers. Exposure to high content (>18% of total dust deposited in lung) of free crystalline silica results in classic silicosis, whereas mixed dust fibrosis develops in the presence of low silica content (<18% of total dust deposited in lung), particularly with simultaneous inhalation of other minerals, such as nonfibrous silicate (e.g., mica, kaolin, coal, talc, fuller’s earth). These nonfibrous silicates augment the strong fibrotic effect of crystalline silica. Instead of the well-defined, whorled appearance found in the silicotic nodule, the lesions in mixed dust fibrosis are characterized by irregular-shaped fibrotic nodules, often called stellate nodules, and a predilection of the fibrotic lesion to extend into the surrounding pulmonary interstitium.

Coal Workers’ Pneumoconiosis

The pathology of CWP is distinct from that of silicosis. Although both lesions tend to surround respiratory bronchioles, there is no collagen deposition or hyalinization in CWP lesions. The histologic hallmark of simple CWP is the black coal dust macule, which represents focal deposition of coal dust and pigment-laden macrophages, usually around respiratory bronchioles. As the macules enlarge, they coalesce with other macules to form a discrete network of interstitial fibrosis that results in dilation of respiratory bronchioles, forming focal areas of emphysema. These areas of focal emphysema can accrue to large volumes without causing significant respiratory impairment.

With increased exposure to coal mine dust, nodular lesions develop at the bifurcations of respiratory bronchioles against a background of macules, mostly in the upper lobes. Compared with the nonpalpable macules, these nodules are firm and palpable and can be classified according to their size as micronodules (≤7 mm diameter) and macronodules (8 mm–2 cm). Microscopically, the nodules are composed of heavily coal dust–laden macrophages interlaced with collagen fibers oriented in a haphazard manner. The margins of the nodules may be round, irregular, or stellate. The fibrous stroma is composed of mature and immature collagen and reticulin.

With chronic dust exposure, the nodules of simple CWP coalesce to produce black, rubbery parenchymal fibrous masses resulting in complicated CWP or PMF. These PMF lesions usually are sited in the posterior aspects of the upper lobes and may encroach on and destroy vascular supply and airways or may cavitate. Microscopically, PMF lesions appear as coal dust–laden, irregular or round, well-demarcated fibrotic masses of collagen bundles and haphazardly laid hyalinized collagen fibers intertwined with reticulin. Lesions also may appear as amorphous collagenization or clusters of nodules. As with silicosis, there is a tendency for PMF to progress with or without further exposure. Despite its similarities with conglomerate silicosis, however, the development of PMF in coal workers is unrelated to silica content of the coal.

Lung Function

Lung function impairment is not a prerequisite for the diagnosis of pneumoconiosis, which rests on a reliable history of sustained occupational exposure to inhaled dust and a chest radiograph that is abnormal according to the ILO’s International Classification of Radiographs of Pneumoconiosis. Lung function evaluation should be used only to quantify clinical disability, particularly for compensation purposes. Lung function impairment in silicosis and CWP may be confounded by the effects of cigarette smoking. Lung function may be normal in the early stages of silicosis or CWP. When present, the lung function impairment may be restrictive, obstructive, or a combination of both. Reduction in diffusing capacity may also be observed.

Manifestations of the Disease

Radiography

Silicosis and CWP are virtually indistinguishable radiologically. The chest radiograph remains the foremost imaging modality by which silicosis and CWP are diagnosed, and disease progression is monitored. However, as an imaging tool, the chest radiograph is relatively insensitive and nonspecific, which can result in underestimation or overestimation of the extent of disease. In addition, a normal chest radiograph does not rule out interstitial fibrosis. Despite these limitations, the ease of performing the study combined with its cost-effectiveness makes radiography almost indispensable.

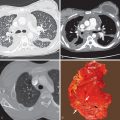

In the ILO radiographic classification, the radiographic opacities are characterized by their size and shape. Small, rounded opacities are described as “p,” “q,” or “r” according to their size (“p,” < 1.5 mm; “q,” 1.5–3 mm; “r,” 3–10 mm) ( Fig. 62.1 ), whereas irregular opacities of similar size are denoted as “s” (<1.5 mm), “t” (1.5–3 mm), and “u” (3–10 mm). Profusion of nodules is a measure of the concentration of small opacities per unit area or zone of lung, determined from comparison of the patient’s chest radiograph with standard radiographs provided by the ILO.

There are 12 categories of profusion, which represent a continuum of changes ranging from normal to severe profusion. These can be grouped into four broad categories based on the degree of obscuration of vascular lung markings by the nodules: category 0 (0/−, 0/0, 0/1), when small opacities are absent or less than category 1; category 1 (1/0, 1/1, 1/2), when small opacities are present in small numbers with normal lung markings; category 2 (2/1, 2/2, 2/3), when numerous small opacities are present, and when lung markings are partially obscured; and category 3 (3/2, 3/3, 3/+), when very numerous small opacities totally obscure normal vascular markings (see Fig. 62.1 ). Patients with scores 1/0 or greater are considered to have pneumoconiosis. A separate classification for large opacities (>1 cm in diameter) exists whereby A denotes one or more opacities greater than 1 cm but smaller than 50 mm; B denotes one or more opacities greater than A, combined area less than the right upper zone; and C denotes one or more opacities whose combined area is greater than the area of the right upper zone.

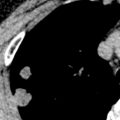

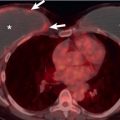

Silicosis

The nodules of simple silicosis are well defined and small (1–10 mm in diameter) and found diffusely in the lungs with posterior and upper lung zone predominance ( Fig. 62.2 ; see Fig. 62.1 ). Nodule calcification is evident in 20% of cases on the chest radiograph, although the incidence is higher on computed tomography (CT). PMF lesions are commonly found at the upper lung zones with smooth or irregular borders, initially at the outer two-thirds of the lung with slow migration toward the hilum over time ( Figs. 62.3 and 62.4 ). PMF has been described to have an angel’s wing appearance on chest radiographs. Punctate, linear, or massive calcifications of the PMF lesions may be found. Classically, paracicatricial emphysema is interposed between the PMF lesion and the pleura accompanied by volume loss in the upper lobes. The presence of paracicatricial emphysema and lung volume loss helps to distinguish unilateral PMF from lung cancer. With increasing severity of PMF and shrinkage of the upper lobes, nodularity is noticeably reduced in the rest of the lung (see Fig. 62.4 ).

Accelerated silicosis has similar radiographic features as the classic form of silicosis except for its earlier onset and rapid rate of progression, which is truncated to a period of 5 to 10 years ( Fig. 62.5 ). Silicoproteinosis is a variant characterized by rapid and progressive involvement of the lungs, which, based on older case reports, may manifest with extensive bilateral ground-glass opacities similar to the findings in alveolar proteinosis ( Fig. 62.6 ). However, more recent work suggests this more frequently manifests with dependent consolidation, often containing foci of calcification, diffuse solid centrilobular nodules, or more patchy ground-glass opacities. The rate of progression ranges from a few months to 1 to 2 years, usually culminating in death in a few years.

Rheumatoid pneumoconiosis (Caplan syndrome) manifests as multiple diffuse, well-defined nodules ranging from 5 mm to 5 cm distributed with peripheral predominance ( Fig. 62.7 ). Characteristically, these nodules appear suddenly within a few months during the follow-up of patients. It may be impossible to distinguish silicotic-type nodules of rheumatoid pneumoconiosis from silicotic nodules.

Lymph node involvement in silicosis reflects the pathogenesis of the disease, and hilar lymphadenopathy on the chest radiograph is common. Eggshell calcifications of lymph nodes have become synonymous with silicosis since they were first described more than half a century ago and are mainly referable to the hilar lymph nodes ( Fig. 62.8 ; see Fig. 62.1 ), although abdominal lymph nodes also have been described to bear eggshell calcifications. Their presence in coal and metal miners has been attributed to the concomitant exposure to silica.