Snapping hip is a common cause of hip complaints, so radiologists should have it on their radar when involved in the workup and care of young patients with hip complaints, especially those whose symptoms are localized to the greater trochanter or iliopsoas. Although history and physical examination often suggest the correct diagnosis, imaging evaluation, including ultrasonography and MR imaging, is valuable to identify responsible extra-articular structures, assess for the presence of any concurrent intra-articular pathology, identify underlying anatomic variants that might necessitate alterations in surgical technique, and guide steroid injections.

Key points

- •

Snapping hip is believed to be present in 5% to 10% of the population, is often bilateral, and is most common in young athletic people.

- •

Although most cases are attributable to extra-articular etiologies related to the greater trochanter or iliopsoas, some patients’ symptoms are attributable to intra-articular pathology, while other patients have both extra-articular and intra-articular abnormalities.

- •

Radiographs, static and dynamic ultrasonography, and MR imaging all play important roles in identifying responsible anatomic structures to guide management and alert clinicians to underlying anatomic variants and conditions. Additionally, ultrasonography can guide steroid injections, which can be diagnostic and therapeutic.

Introduction and definitions

Snapping hip (sometimes called by its Latin name, coxa saltans) is a clinical entity in which a sudden sensation is experienced in the vicinity of the hip during certain kinds of movement. This sensation might be described as a snap, click, pop, or crack, or as locking or getting stuck. Some people may mistake their snapping hip for transient hip joint dislocation-relocation events. In low-grade forms of the entity, the snapping event is noticeable to the person experiencing it but cannot be palpated by an orthopedist’s hands on physical examination. In higher-grade forms of the entity, the event is palpable to an examiner’s hands and may even be externally visible or audible.

Snapping hip is sometimes painful to the person experiencing it, while in other cases it is painless. The true proportion of cases that are painful may never be determined with certainty, as many painless cases probably never come to medical attention, but it has been reported that around 50% to 70% of snapping hip cases are painful. , The term snapping hip syndrome is sometimes used synonymously with snapping hip, but some have advocated that this term be reserved for only those cases that are painful. In addition to being painful, snapping hip may interfere with such activities as running, ascending stairs, toting loads, standing up from sitting, and getting into and out of cars.

Epidemiology and risk factors

Snapping hip is thought to be present in 5% to 10% of the population; it has been reported that about half of cases are bilateral. The external form is believed to affect the sexes equally, while the internal form affects women more than in men, perhaps because of the higher frequency of such underlying entities as developmental hip dysplasia in women (the terms external snapping hip and internal snapping hip will be defined in the following section of this article). Snapping hip is the third most frequently seen hip abnormality in the young female population.

Snapping hip is most found in people in their teens and twenties, especially those who have not yet reached skeletal maturity. It has a predilection for those involved in athletic endeavors that require repetitive extreme hip rotation, such as ballet, other dance, gymnastics, running (especially on slopes), CrossFit, soccer, football, and weightlifting. Overweight people may be at increased risk also, because of a higher likelihood of psoas muscle hypertrophy. Other potential risk factors include leg length discrepancy, trauma, and a history of intervention or surgery such as total hip arthroplasty or knee reconstruction. Coxa vara has also been implicated, as it has been postulated to increase stress on the iliotibial band by weakening the hip-abducting forces of the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus.

Classification: extra-articular versus intra-articular, lateral versus medial

Snapping hip may be classified as either intra-articular or extra-articular. Etiologies of intra-articular snapping hip may include transient hip joint subluxations, labral tears with or without paralabral cysts, ligamentum teres tears, osteochondral fractures, primary and secondary synovial osteochondromatosis, thick synovial folds, and other causes of hip derangement. Recently, the phrase intra-articular snapping hip has fallen somewhat out of favor and been replaced by terms like mechanical symptoms, locking, or catching. When compared with extra-articular snapping hip, intra-articular snapping hip is more consistently painful, more acute in onset, more likely to be preceded by trauma, and more likely to require eventual surgery, such as labral repair, loose body removal, or arthroplasty.

Extra-articular snapping hip can be further subdivided into 2 categories: lateral extra-articular snapping hip (sometimes called external extra-articular snapping hip, or coxa saltans externa in Latin) and medial extra-articular snapping hip (sometimes called anterior extra-articular snapping hip, internal extra-articular snapping hip, or coxa saltans interna in Latin).

Lateral extra-articular snapping hip is widely thought to be the most common form of snapping hip. Its most common cause is abnormal movement of the posterior portion of the iliotibial band over the greater trochanter. However, lateral extra-articular snapping hip may also be caused by abnormal movement of the anterior portion of the gluteus maximus muscle over the greater trochanter. Rarer causes include abnormal movement of the iliotibial band or gluteus maximus muscle over a distended greater trochanteric bursa ( Fig. 1 ) or over orthopedic hardware. Lateral extra-articular snapping hip is often visible but not audible to an external observer.

Because of its association with the greater trochanter, lateral extra-articular snapping hip, when painful, might be regarded as a special subcategory of the broader category of conditions that collectively go by the name of greater trochanteric pain syndrome. However, whereas greater trochanteric pain syndrome most commonly afflicts middle-aged patients with gluteus medius or gluteus minimus tendon tears or greater trochanteric bursitis, snapping hip is distinctive in that, as mentioned previously, it is predominantly found in young athletic people.

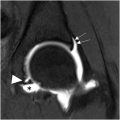

Medial extra-articular snapping hip is usually caused by iliacus muscle movement, resulting in the iliopsoas tendon first becoming embedded in the iliacus muscle and then falling back into its prior position; in this process, the iliopsoas tendon snaps over such structures as the iliopubic eminence (which lies just medial to the iliopsoas tendon groove), the anterior inferior iliac spine (which lies just lateral to the iliopsoas tendon groove), the lesser tuberosity, the femoral head and anterior hip joint capsule, a paralabral cyst, a distended iliopsoas bursa, or a prosthetic acetabular cup ( Fig. 2 ). Snapping of the iliopsoas tendon over a prominent prosthetic acetabular cup has been said to be responsible for 4.3% of cases of post-total-hip-arthroplasty pain.

In the setting of a bifid iliopsoas tendon, medial extra-articular snapping hip may be caused by abnormal movement of the tendon’s medial head over its lateral head. Medial extra-articular snapping hip may also be caused by abnormal movement of the iliofemoral ligament over the femoral head. Rarely, medial extra-articular snapping hip may be secondary to tendinosis or calcific tendinopathy of the rectus femoris tendon. Medial extra-articular snapping hip is characteristically audible but not visible to an external observer.

Although the previous description is a useful classification scheme, it is important to remember that having concurrent extra-articular and intra-articular hip pathology is not uncommon: having extra-articular pathology can increase the likelihood of intra-articular pathology (eg, labral tear secondary to iliopsoas impingement), and vice versa.

Physical examination

A good history and physical examination often suffice to make the diagnosis of snapping hip. In the most clear-cut cases, the patient provides a history of a snapping sensation with hip motion. Generally, when asked, the patient will be able to indicate the site of snapping (eg, lateral or medial) by pointing to it with 1 finger.

Snapping can be reproduced on physical examination such that the patient feels it, and additionally the examiner may be able to feel it with his or her hands and perhaps even hear or see it. For lateral extra-articular snapping hip, the snapping may best be elicited with the patient in decubitus position lying on his or her unaffected side, flexing and extending the affected hip actively or passively. Additionally, for lateral extra-articular snapping hip, the snapping may be preventable on physical examination by the examiner placing pressure on the greater trochanter with their hands, and there may be tenderness over the greater trochanter also. In addition to the decubitus position, Yen and colleagues also recommend having the patient stand and circumduct their hips in order to reproduce the snapping, a test they call the hula-hoop test.

For lateral extra-articular snapping hip, a positive Ober test for iliotibial band tightness may help confirm the diagnosis. For medial extra-articular snapping hip, Thomas’ test for psoas contracture may be positive, and concomitant gluteus medius weakness may be present. For intra-articular snapping hip, the FAdIR (flexion, adduction, and internal rotation) test for intra-articular pathology may be positive.

Radiography, computed tomography, and fluoroscopy

In less obvious cases, imaging can be helpful for making the diagnosis of snapping hip, excluding competing entities, determining which anatomic structures are responsible, and assessing for secondary changes to the soft tissues that may contribute to pain and symptoms. Imaging, especially with ultrasonography or MR imaging, is also important for excluding underlying anatomic variants such as a bifid iliopsoas tendon, which, if missed, could result in failed surgical management.

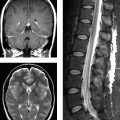

Radiographs are the first-line imaging test and can be useful to reveal underlying abnormalities such as developmental hip dysplasia, coxa vara, and cam deformities (the latter may predispose not only to femoroacetabular impingement but also to snapping of the iliopsoas tendon across the femoral head). Radiographs are also valuable in providing evidence suggestive of intra-articular snapping hip such as osteoarthropathy or synovial chondromatosis. Computed tomography (CT) may be helpful for making the same kinds of findings, and for assessing acetabular and femoral version (acetabular anteversion may be associated with snapping, and Fabricant and colleagues showed that femoral anteversion of at least 25° is associated with worse outcomes after certain surgeries performed for medial extra-articular snapping hip).

In the past, iliopsoas tenography and bursography with fluoroscopy were performed more frequently, but nowadays these techniques are practiced less often because of concerns about their invasive nature and the risks of radiation and contrast administration.

Currently, ultrasonography and MR imaging are the 2 imaging modalities most informative in the workup of snapping hip.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is inferior to MR imaging in being operator-dependent, in having limited sensitivity for intra-articular causes of snapping hip, and in having limited ability to visualize deep extra-articular soft tissues, especially in patients of overweight or obese body habitus. Ultrasonography is superior to MR imaging in its cheapness, its relative lack of compromise from hardware-related artifacts, and, most especially, its ability to provide dynamic assessment during patient movement designed to reproduce the snapping symptoms.

When performing ultrasonography for suspected snapping hip, either a linear or curved transducer could be used, depending on patient body habitus considerations. For many patients, a 5 to 12 MHz transducer will be most appropriate. Ultrasonographic investigation can include the anterior, medial, lateral, and posterior aspects of the involved hip, with the patient being asked to assume a frog-leg (ie, flexed, abducted, and externally rotated) position when it is time to scan the medial aspect of the hip. It can be helpful to obtain comparison images of the asymptomatic contralateral hip (assuming that the contralateral hip is asymptomatic), so that tendon thicknesses on the 2 sides of the body can be compared.

Both static images and dynamic (cine) images should be obtained. When obtaining dynamic images, the patient should be asked, if possible, to move his or her hip in a way that reproduces the snapping sensation. Some types of movements that may fit the bill include moving the hip from a frog-leg position to an extended position, moving the hip from an extended position to a frog-leg position, moving the hip from flexion to extension, moving the hip from extension to flexion, or moving the hip from an extended position to a flexed and internally rotated position. It is helpful to have an assistant available to manually support the patient’s lower extremity during dynamic maneuvers.

The ultrasonographic findings will vary depending on etiology. If the cause for the snapping hip is extra-articular, then tendinosis of the iliotibial band, iliopsoas tendon, or rectus femoris tendon could be seen, discernible as decreased echogenicity and attenuation of the affected structure, and increased thickness of the affected structure when compared with its counterpart on the contralateral side. Focal tenderness may also be elicited when the transducer is pressed against the iliotibial band, iliopsoas tendon, or rectus femoris tendon. If the iliopsoas is the responsible party, then static ultrasonographic images could show iliopsoas bursitis, which manifests as thickening, fluid distention, and/or Doppler hyperemia of the iliopsoas bursa. However, seeing these findings on ultrasonographic images in snapping hip is not common. Trochanteric bursitis may also be seen, visible as thickening, fluid distention, and/or Doppler hyperemia of the trochanteric bursa. If the etiology is intra-articular, then static ultrasonographic images may show hip joint synovitis, manifesting as synovial thickening, synovial hyperemia on Doppler imaging, and/or joint effusion.

Dynamic ultrasonographic images are especially valued in clinching the diagnosis. If abnormal iliotibial band movement is the cause of snapping hip, then, when the transducer is placed in the short-axis plane over the greater trochanter while the patient is lying in decubitus position on their contralateral side, the iliotibial band will jerk abruptly in a posterior direction when the hip is being extended or in an anterior direction when the hip is being flexed ( Fig. 3 B, C ).