Clinical Considerations

Ultrasound is an ideal modality to supplement evaluation of the soft tissue. The high–frequency linear transducer produces a detailed image of the area in question. By adding dynamic interrogation, such as manual compression or color flow, we can further characterize the findings to help confirm or rule out many common diagnoses.

Soft tissue infections, including cellulitis and abscess, are extremely prevalent, and becoming more so, with emergency department (ED) visits for these conditions more than doubling in recent years. Clinically, these infections present as areas of erythema, edema, induration, warmth, and sometimes with fluctuance. It can be challenging to differentiate between cellulitis and abscess based on physical examination alone, but the distinction is important, as they require different management. Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has been shown to reliably diagnose an abscess with sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 83%. When an abscess is identified, POCUS can then be used to guide incision and drainage (I&D), reducing treatment failures.

POCUS is also useful for localizing and removing foreign bodies. In the ED and outpatient settings, foreign bodies are most commonly lodged in the hand or foot. Missed foreign bodies can lead to increased infection rates, delayed healing, and pain. X-ray is at times unreliable for identifying and localizing foreign bodies. Some materials, such as metal, bullets, gravel, or glass, may be radio-opaque, but plastic and organic material, such as wood or thorns, and some types of glass, are radiolucent and difficult to identify with X-ray. POCUS identifies most foreign bodies and is also useful to guide removal.

Anatomy

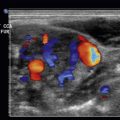

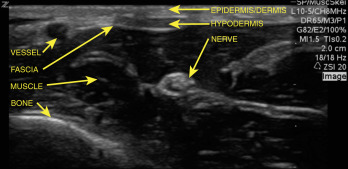

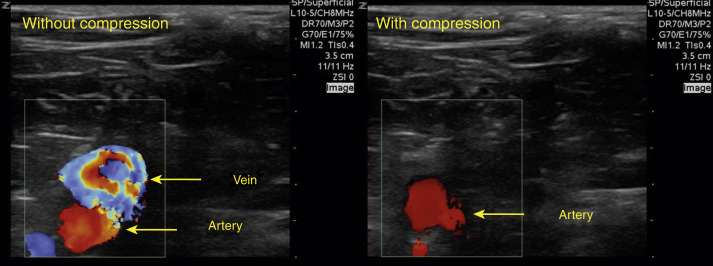

Soft tissue anatomy has a reliable appearance on ultrasound ( Fig. 27.1 ). The most superficial layer is the skin, composed of epidermis and dermis, which generally appears on ultrasound as a thin, hyperechoic layer, closest to the probe. Below the skin is the subcutaneous tissue, or hypodermis, which varies in thickness and contains hyperechoic fat with hypoechoic septa, as well as blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatics. Vessels appears as tubular structures with a hyperechoic wall and anechoic center. Nerves have a honeycomb appearance in the short axis and appear striated in the long axis. Nerves exhibit anisotropy, appearing more hyperechoic or hypoechoic, depending on the angle of the transducer. Muscle may be superficial or deep to nerves and appear more hypoechoic with hyperechoic striations and fascial planes. Tendons, nerves, and blood vessels also run along the muscle layer. Tendons have a regular, striated appearance and, like nerves, are anisotropic. Bone underlies the muscles in most areas of the body and appears brightly hyperechoic with dark shadowing. Using color flow Doppler with and without compression can help identify vascular structures and differentiate these from other fluid collections ( Fig. 27.2 ).

Cellulitis and abscesses develop in the skin and subcutaneous tissue and are commonly caused by Streptococcus species and Staphylococcus aureus . Abscesses can extend into deeper tissue, including muscle, even reaching bone. POCUS identifies the size and depth of soft tissue infections. In rare cases, necrotizing infections can develop in the muscle (necrotizing myositis) and fascial planes (necrotizing fasciitis) and may appear on ultrasound as gas with ring-down artifact. These infections are often rapidly progressive and can be life threatening. Early identification with POCUS should prompt further workup, including emergent surgical consultation.

When evaluating foreign bodies, it is important to identify key anatomic structures in the area, including nerves, blood vessels, tendons, and lymph nodes, to avoid injuring these structures during foreign body removal. Hands and feet are commonly affected, and it may help to review the anatomy of the specific region of interest before removal.

Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

Preparation and Technique

- 1.

Select a transducer. High-frequency ultrasound provides good resolution at shallow depths, up to about 6 to 8 cm. This is ideal for evaluating most soft tissue infections.

- 2.

Select a setting. Most ultrasound machines will have a “soft tissue,” “small parts,” or similar setting.

- 3.

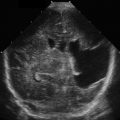

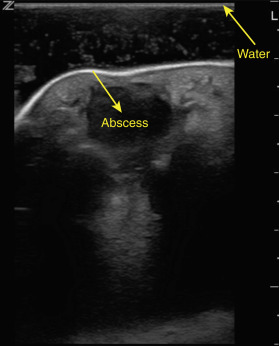

Apply gel. Gel conducts the ultrasound waves, improving the image. For the hands and feet, consider using a water bath. Water is an excellent conductor of sonographic waves and provides very clear images, and the examination is essentially pain free for the patient ( Fig. 27.3 , Video 27.1

). Hold the transducer perpendicular to the skin and keep it approximately 1 to 2 cm above the skin to maximize image quality. If a water bath is not available or feasible, you may choose to scan through a saline bag or a glove filled with water.

). Hold the transducer perpendicular to the skin and keep it approximately 1 to 2 cm above the skin to maximize image quality. If a water bath is not available or feasible, you may choose to scan through a saline bag or a glove filled with water.

Fig. 27.3

Abscess visualized using a water bath.

- 4.

Explore deep and shallow fields. Whereas cellulitis is generally more superficial, abscesses can extend into deeper tissues. It is important to determine the depth of the fluid pocket and its relationship to structures underlying the skin.

- 5.

Evaluate in two orthogonal planes. Generally, an area is imaged in both long (sagital or coronal) and short (transverse) planes. This helps characterize the shape and size of the infection.

- 6.

Follow the findings. Trace the fluid collection in all directions to determine the size and extent of the infection.

- 7.

Identify surrounding anatomy. This is important for procedural planning. Identify nearby bones, muscles, tendons, nerves, vessels, and lymph nodes. Use color Doppler as appropriate to clarify structures.

Ultrasound Findings

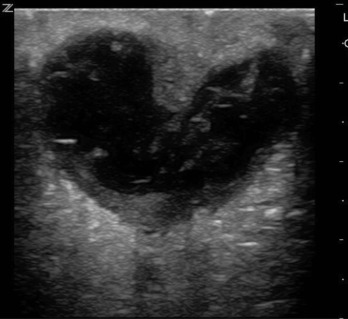

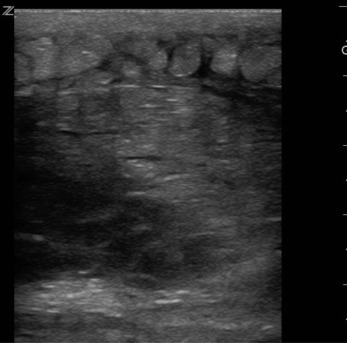

In a patient with cellulitis, the subcutaneous tissue takes on a characteristic “cobblestone” appearance ( Fig. 27.4 , Video 27.2 ![]() ). Hypoechoic edema in the tissue surrounds and delineates the hyperechoic fat lobules. Note that the fluid seen in cobblestoning thinly outlines the fat lobules, but does not form large pockets.

). Hypoechoic edema in the tissue surrounds and delineates the hyperechoic fat lobules. Note that the fluid seen in cobblestoning thinly outlines the fat lobules, but does not form large pockets.

In contrast, an abscess generally appears as a predominantly anechoic pocket, sometimes with mixed internal echoes caused by fibrinous debris ( Fig. 27.5 , Video 27.3 ![]() ). These fluid pockets may be well contained with a distinct hyperechoic wall, or they may be more infiltrative, with loculations extending in several directions into the subcutaneous tissue. Adjust your depth to include the bottom of the fluid pocket, and slide the transducer along the skin in two orthogonal planes to visualize the entire abscess cavity. Use the depth markers on the right side of the screen to assess the depth of the fluid collection. Light compression of the abscess may result in a “swirl sign” caused by fibrinous debris moving in the fluid component of the abscess. Cobblestoning may or may not be present in the tissue surrounding the abscess. Abscesses on the hand or foot can be imaged utilizing a water bath (see Fig. 27.3 ).

). These fluid pockets may be well contained with a distinct hyperechoic wall, or they may be more infiltrative, with loculations extending in several directions into the subcutaneous tissue. Adjust your depth to include the bottom of the fluid pocket, and slide the transducer along the skin in two orthogonal planes to visualize the entire abscess cavity. Use the depth markers on the right side of the screen to assess the depth of the fluid collection. Light compression of the abscess may result in a “swirl sign” caused by fibrinous debris moving in the fluid component of the abscess. Cobblestoning may or may not be present in the tissue surrounding the abscess. Abscesses on the hand or foot can be imaged utilizing a water bath (see Fig. 27.3 ).