Clinical Presentation

The patient is a 71-year-old man with small cell lung cancer and known brain metastases who presents with new onset of right-sided weakness and sensory disturbances. His symptoms began approximately 2 to 3 weeks ago and have been getting progressively worse. He describes weakness on his right side, mainly involving his right hand and proximal right leg. He also notes numbness on his entire right side, involving his face, arm, trunk, and leg. His weakness has progressed to the point where he has difficulty writing, holding a pen or fork, and he has had three falls in the past 3 weeks because of gait instability. He has started using a walker to prevent falling. He denies having any bowel or bladder incontinence. He has developed headaches in the past 3 weeks, which he describes as dull in nature and frontal in location.

Imaging Presentation

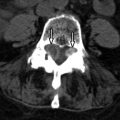

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging reveals an enhancing intramedullary mass in the cord from C5 to C7 level. Above this level is diffuse cord enlargement secondary to edema that extends into the lower brainstem (medulla). Findings are consistent with intramedullary spinal cord metastasis ( Figs. 70-1 to 70-3 ) .

Discussion

Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis is a rare tumor, occurring in less than 2% of autopsied cancer patients. Intramedullary metastases represent only 1% to 3% of spinal cord metastases. An intramedullary metastasis may arise anywhere in the spinal cord but more frequently occurs in the cervical cord (see Figs. 70-1 to 70-3 ), followed by the thoracic cord ( Figs. 70-4 and 70-5 ) , conus medullaris ( Figs. 70-6 and 70-7 ) , and cauda equina. Any primary malignant neoplasm can metastasize to the spinal cord, but lung carcinoma (especially small cell lung carcinoma) is by far the most common primary tumor to metastasize to the cord, followed by breast carcinoma, melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, colorectal carcinoma, lymphoma, and rarely other primary tumors. These primary tumors are believed to spread to the spinal cord hematogenously, but retroperitoneal tumors can spread via Batson’s plexus or perineural lymphatics. Central nervous system (CNS) malignancies, such as glioblastoma multiforme, ependymoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor (e.g,. medulloblastoma), and rarely other intracranial tumors, can metastasize to the spinal cord by spreading within the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). These primary tumors usually deposit along the leptomeningeal surface of the spinal cord or cauda equina, rather than depositing in the cord centrum.

Uncommonly, intramedullary metastases may hemorrhage, and the resulting blood may extend into the CSF surrounding the cord, causing a subarachnoid hemorrhage. Rarely, a syrinx cavity develops adjacent to an intramedullary metastasis.

Nearly all patients with intramedullary metastases present with myelopathy, more than 90% of patients having a motor deficit, either acute onset of weakness or rapidly progressive paraparesis over a few weeks ; 70% of patients present with back pain, but paresthesias and bladder and/or bowel dysfunction are also common, depending on the location of the tumor. The patient may present with Brown-Séquard syndrome.

Imaging Features

MRI is the imaging procedure of choice for diagnosing and assessing the extent of spinal cord metastases (see Figs. 70-1 to 70-7 ). In the initial workup of these patients, a lumbar puncture is usually performed to examine the CSF for positive cytology. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scanning has also been shown to be sensitive for detection and assessing the extent of intramedullary and leptomeningeal metastases. Imaging abnormalities of cord metastasis are usually not visible on radiographs or by plain computed tomography (CT). Fusiform enlargement of the cord, if present, is visible at myelography, but this fusiform enlargement is nonspecific, occurring with intramedullary tumors, vascular anomalies, and syringohydromyelia. Most intramedullary metastases are solitary, with an average cephalocaudal extent of two to three vertebral segments.

Unenhanced, T1-weighted MR images may be normal but frequently show fusiform cord enlargement or may demonstrate a subtle region of T1 hypointensity in the cord, which can be confused with an intramedullary syrinx (see Fig. 70-2 ). True syrinx cavities rarely coexist with an intramedullary metastasis. The intramedullary metastasis and adjacent edema are T2 hyperintense, unless hemorrhage is present, which may be T2 hypointense, hyperintense, or of mixed intensity. There is often a considerable amount of edema in the cord adjacent to an intramedullary metastasis (see Fig. 70-1 ). Occasionally, the intramedullary metastasis may appear only slightly T2 hyperintense with little or no adjacent edema (see Figs. 70-4 and 70-6 ). The cord edema, when present, may be relatively localized or extend over a long cephalocaudal distance. The typical intramedullary metastasis enhances intensely, but the pattern of enhancement may be homogeneous or heterogeneous (see Figs. 70-3, 70-4, 70-6, and 70-7 ). The enhancing portion of the intramedullary lesion is usually one to three vertebra in cephalocaudal length, and tends to be relatively small in comparison with the amount of associated cord edema, when edema is present (see Fig. 70-3 ). Uncommonly, the cord metastasis enhances in a ringlike fashion.

If an intramedullary metastasis is discovered with MR imaging, whole body F-18 FDG-PET scanning is recommended to exclude other metastases within and outside of the CNS, because there is a high incidence of other metastases in patients presenting with an intramedullary metastasis. Approximately 75% of patients with an intramedullary metastasis have systemic metastases, and 35% have CNS metastases elsewhere.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree