Clinical Presentation

The patient is a 75-year-old man who presented with 4 weeks of low back pain and bilateral lower extremity pain. He states he was lifting some sand and felt pain in his lower back and hips. He states that he fell off a ladder while climbing 4 weeks ago. He has had a total of five falls, and states that he has no warning, but simply collapses. This is preceded immediately by a sharp pain in his back. He occasionally gets this same pain when he turns in bed or bends forward. He has problems when he is coughing while sitting down, but no problems when coughing if he is lying supine or standing up. On physical examination, there is no neurologic deficit. Straight leg raise was negative. Reflexes were symmetric bilaterally in the lower extremities. He is otherwise without problems. No specific gait abnormality is appreciated.

Imaging Presentation

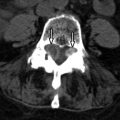

Sagittal and axial T1-weighted images demonstrate anterior subluxation of L5 relative to S1 with approximately 40% uncovering of the disc compatible with a grade 2 spondylolisthesis. There is widening of the spinal canal, which is seen with subluxations secondary to defects in the pars interarticularis/spondylolysis. Typically, there is spinal stenosis with degenerative spondylolisthesis and usually no greater than a grade 1 subluxation, because the intact pars interarticularis limits the amount of movement of one vertebral body relative to the next ( Fig. 74-1 ) .

Discussion

Spondylolisthesis is defined as the slipping of one vertebral body with respect to an adjacent vertebral body. Generally, the direction of slip is defined as the more cephalad vertebral body in relation to the adjacent, inferior vertebral body. Anterolisthesis is defined as anterior slipping of the cephalad vertebral body in relation to the inferior one. Retrolisthesis is posterior slipping of the cephalad vertebral body in relation to the inferior one. One may also refer to lateral listhesis when there is slippage of a vertebral body left or right compared with the inferior vertebral body, which is readily seen with coronal reformatted images.

The various types of spondylolisthesis are divided into six subgroups; degenerative, isthmic, congenital/dysplastic, traumatic, pathologic, and iatrogenic. The isthmic lytic lesion of the pars interarticularis is the most common cause of spondylolisthesis and is called spondylolysis. The pars defect is what differentiates degenerative spondylolisthesis from isthmic spondylolisthesis.

The pars interarticularis, also known as the isthmus , is that portion of the neural arch that connects the spinal lamina with the pedicle, facet joints, and transverse process. Roughly, on oblique views, it is midway between the superior and inferior articular process ( Fig. 74-2 ) . Because of its shape and location, the pars interarticularis is subject to the greatest force of any structure in the lumbar spine, but unfortunately may be the weakest part of the neural arch.

Spondylolytic spondylolisthesis is the most common cause of spondylolisthesis. The incidence of spondylolysis ranges from 4.4% to 5.8% and that of isthmic spondylolisthesis ranges from 2.6% to 4.4%. In other words, 50% to 81% of patients with spondylolysis have spondylolisthesis. Isthmic spondylolisthesis occurs twice as often in males as females, however, females are four times more likely to have progression of the slippage. Spondylolysis appears to be multifactorial in origin with mechanical, congenital, and potentially hormonal factors. Spondylolysis is commonly seen with athletic participation, particularly in gymnasts, football linemen, weightlifters, wrestlers, and divers. Spondylolysis is the most common cause of low back pain in young athletes and is seen in 47% of young athletes complaining of low back pain. It has been postulated that the repetitive forces of flexion, hyperextension, and rotation required in these sports results in stress fractures of the pars. Inheritance studies have shown a high incidence of spondylolysis with spondylolisthesis in near relatives with the same process. Although the incidence of spondylolysis ranges from approximately 4% to 6% in the general population, the incidence in near relatives is approximately 25% to 30%. Progression of vertebral slippage has been noted during adolescence, which could imply hormonal influences or growth factors in the development of spondylolisthesis.

The most common level of a pars defect is L5. The L5 level is involved in 70% to 95% of cases, the L4 level in 5% to 20% of cases, and other areas throughout the spine in the remaining cases.

Pain is the typical manifesting symptom in patients with isthmic spondylolisthesis. This may be low back pain and/or radicular pain. The pain is often a deep ache that is localized to the lumbar area, which may radiate to the buttocks or posterior thighs. Weight bearing and lifting exacerbate the symptoms, whereas rest and recumbency relieve it. Radicular pain is often in the L5 distribution, either unilateral or bilateral. With higher grade subluxations, the cauda equina can be stretched over the sacrum, which can lead to signs and symptoms of cauda equina syndrome, including perineal numbness, sphincter disturbances, and S1-related symptoms.

Imaging Features

Spondylolysis can often be visualized with plain radiographs. The oblique radiograph can identify the defect of the par interarticularis (also known as the collar of the “Scottie Dog”) ( Fig. 74-3 ) . The lateral radiograph demonstrates anterior or posterior displacement of one vertebral body in comparison to an adjacent vertebral body. One can see widening of the spinal canal when there is spondylolysis associated with spondylolisthesis ( Fig. 74-4 ) . This is in contrast to the narrowing of the anteroposterior diameter of the spinal canal seen with degenerative spondylolisthesis. Lateral flexion and extension radiographs are important to evaluate for any dynamic motion of the abnormal segment and to evaluate for reduction of the spondylolisthesis. Computed tomography (CT) is more sensitive in evaluating the cause of the slip and can readily demonstrate a spondylolytic defect ( Fig. 74-5 ) . With CT, one is better able to evaluate the effect of the slippage in relation to neural foraminal impingement and lateral recess stenosis. CT with sagittal reformatted images best demonstrate the elongation of the affected neural foramen and the degree of nerve root compromise ( Fig. 74-6 ) .

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree