Chapter Outline

Pharyngeal Pouches and Diverticula

Lateral Pharyngeal Pouches and Diverticula

Branchial Cleft Cysts, Branchial Cleft Fistulas, and Branchial Pouch Sinuses

Pharyngeal and Cervical Esophageal Webs

Inflammatory Lesions of the Pharynx

Malignant Tumors of the Pharynx

Pharyngeal Damage from Radiation

Surgery for Tongue and Oropharyngeal Cancers

Surgery for Zenker’s Diverticulum and Pharyngeal Pouches

Pharyngeal Pouches and Diverticula

Lateral Pharyngeal Pouches and Diverticula

The lateral pharyngeal wall may protrude beyond the normal expected contour of the pharynx in areas unsupported by muscle layers. The upper anterolateral pharyngeal wall is poorly supported in the region of the posterior and superior portions of the thyrohyoid membrane. This region is bounded superiorly by the greater cornu of the hyoid bone, anteriorly by the thyrohyoid muscle, posteriorly by the superior cornu of the thyroid cartilage and stylopharyngeal muscle, and inferiorly by the ala of the thyroid cartilage. This unsupported part of the thyrohyoid membrane is perforated by the superior laryngeal artery and vein and the internal laryngeal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve.

Patients with lateral pharyngeal pouches usually have no symptoms. Approximately 5% of people with lateral pharyngeal pouches complain of dysphagia, choking, or regurgitation of undigested food. Lateral pharyngeal pouches are extremely common, and the frequency of their occurrence increases with age. The pouches are usually bilateral.

On frontal views during swallowing, pouches appear as transient, hemispheric, contrast-filled protrusions from the lateral hypopharyngeal wall, below the hyoid bone and above the calcified edge of the thyroid cartilage ( Fig. 16-1 ). The junction of the ala of the thyroid cartilage and thyrohyoid membrane is seen on frontal views as a notch in the lateral pharyngeal wall. On double-contrast frontal views in which a modified Valsalva maneuver is performed, the pouches are seen as hemispheric, barium-coated protrusions above the notch in the lateral pharyngeal wall. On lateral views, the pouches are seen as oval ring shadows (occasionally with an air-contrast level) below the hyoid bone at the level of the valleculae, just behind the epiglottic plate, along the anterior hypopharyngeal wall. Barium that is retained in pouches during swallowing spills into the ipsilateral piriform sinus after the bolus passes. This delayed spill may result in dysphagia or a choking sensation because of overflow aspiration.

In contrast, lateral pharyngeal diverticula are persistent protrusions of pharyngeal mucosa, usually through the thyrohyoid membrane or, rarely, through the tonsillar fossa. The diverticula are lined by nonkeratinizing squamous epithelium surrounded by loose areolar connective tissue, with many vascular spaces. These protrusions are commonly found in those who have increased intrapharyngeal pressure (e.g., wind instrument players, glass blowers, people with severe sneezing episodes). Clinical symptoms may include dysphagia, choking, cough, hoarseness, regurgitation of undigested food, or a painless neck mass. Radiographically, the diverticula are persistent, barium-filled sacs of various sizes connected to a bulging lateral hypopharyngeal wall by a narrow neck ( Fig. 16-2 ). They are usually unilateral.

Laryngoceles

A lateral pharyngeal diverticulum is a protrusion of nonkeratinizing squamous mucosa originating in the pharynx. A laryngocele is a protrusion of ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium and loose areolar connective tissue arising from saccular dilation of the appendix of the laryngeal ventricle. If saccular dilation of the appendix is confined by the thyroid cartilage, it is termed an internal laryngocele. If the dilation extends above the thyroid cartilage and through the thyrohyoid membrane, the sac is termed external laryngocele. A combination of internal and external laryngocele is termed a mixed laryngocele.

Patients with laryngoceles and those with lateral pharyngeal diverticula have similar symptoms and physical findings. Most patients are asymptomatic and in the fifth to sixth decade of life. Patients with external or mixed laryngoceles may have a compressible lateral neck mass. Patients with internal laryngoceles may complain of hoarseness, dysphagia, or choking. Laryngoceles are seen in patients with increased intralaryngeal pressure, such as glass blowers and wind instrument players.

Frontal radiographs in patients with an external laryngocele may show an air-filled sac above and lateral to the ala of the thyroid cartilage. Lateral radiographs may show the air-filled sac anterior to the epiglottic plate, in contrast to a lateral pharyngeal diverticulum, which lies posterior to the epiglottic plate. External and internal laryngoceles do not fill with barium on pharyngograms. However, barium studies may reveal enlargement of the aryepiglottic fold with a smooth overlying mucosa.

Branchial Cleft Cysts, Branchial Cleft Fistulas, and Branchial Pouch Sinuses

In the 4-week-old embryo, paired grooves of ectodermal origin, termed branchial clefts, appear on both sides of the neck region. Branchial ridges (arches) lie between the branchial clefts. Four outpouchings from the pharynx grow to meet the branchial clefts. The pharyngeal outpouchings are of endodermal origin and are termed branchial pouches. The first branchial cleft forms the external auditory meatus. The second branchial cleft forms the middle ear, eustachian tube, and floor of the tonsillar fossa. The third and fourth branchial pouches form the piriform sinuses.

Persistence of branchial pouches or clefts results in the formation of sinus tracts or cysts. The most common branchial vestige is a cyst arising from the second branchial cleft. A second branchial cleft cyst is found at the level of the hyoid bone, deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Pathologically, a unilocular cyst is lined by keratinizing, stratified, squamous epithelium and is filled with desquamated keratinaceous debris. A zone of lymphoid tissue surrounds the epithelium.

Patients with second branchial cleft cysts usually present between the ages of 10 and 40 years with a painless or fluctuant mass in the upper neck along the upper third of the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. When small, the cysts are anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. When large, the cysts may extend posteriorly to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, displacing the carotid sheath.

Cross-sectional imaging of noninfected cysts may reveal a smooth, thin-walled mass with a homogeneous water core. If infected, the wall of the branchial cleft cyst becomes thickened and may enhance with the administration of intravenous contrast medium. The second branchial cleft cyst may extend between the internal and external carotid arteries at a level superior to their bifurcation. Rarely, branchial cleft cysts may communicate with the pharynx (branchial cleft fistulas), filling with barium during pharyngography.

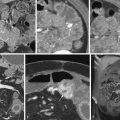

Branchial pouch sinuses or fistulas are tracts that extend from the pharynx and end blindly in the soft tissues of the neck (sinus) or extend to the skin (fistulas). These tracts are lined by ciliated columnar epithelium. Branchial pouch sinuses arise from the tonsillar fossa (second pouch), upper anterolateral piriform fossa (third pouch), or lower anterolateral piriform sinus (fourth pouch; Fig. 16-3 ). Many of these fistulas are present at birth and communicate with the skin. Sinus tracts that end blindly are occasionally seen in adults.

Zenker’s Diverticulum

Zenker’s diverticulum (posterior hypopharyngeal diverticulum) is an acquired mucosal herniation through an area of anatomic weakness in the region of the cricopharyngeal muscle (Killian’s dehiscence). The inferior constrictor muscle is composed of the thyropharyngeal and cricopharyngeal muscles. The thyropharyngeal muscle arises from the lateral ala of the thyroid cartilage; it courses laterally and posteriorly to merge with its counterpart from the opposite side in a raphe in the posterior pharyngeal wall. The cricopharyngeal muscle constitutes the lower portion of the inferior constrictor muscle, arising from the lateral cricoid cartilage to encircle the lowermost hypopharynx. The cricopharyngeal muscle has no midline raphe. No overlap of fibers exists between the thyropharyngeal and cricopharyngeal muscles. Considerable variation is found in the arrangement of the muscle bundles of the thyropharyngeal and cricopharyngeal muscles. Killian’s dehiscence has been variably described as arising between the thyropharyngeal and cricopharyngeal muscles or between the oblique and horizontal fibers of the cricopharyngeal muscle. This area of weakness occurs in one third of patients.

The pathogenesis of Zenker’s diverticulum is as controversial as the muscular anatomy. Some radiographic and manometric studies have suggested that spasm with elevated pressure of the upper esophageal sphincter or incoordination and abnormal relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter (achalasia) are contributing factors. However, other manometric studies have shown the following: (1) there is normal coordination between pharyngeal contraction and relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter; (2) the upper esophageal sphincter relaxes completely during swallowing (i.e., there is no achalasia); and (3) the resting pressure of the upper esophageal sphincter is low (i.e., there is no spasm). The relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and Zenker’s diverticulum is also controversial. Almost all patients with Zenker’s diverticulum have an associated hiatal hernia, and many patients have radiographic evidence of gastroesophageal reflux, reflux esophagitis, or both. Whether gastroesophageal reflux predisposes patients with a large Killian dehiscence to the formation of Zenker’s diverticulum is unknown.

Zenker’s diverticulum is usually found in older patients who have dysphagia, regurgitation of undigested food, halitosis, choking, hoarseness, or a neck mass. Some patients with Zenker’s diverticulum are asymptomatic.

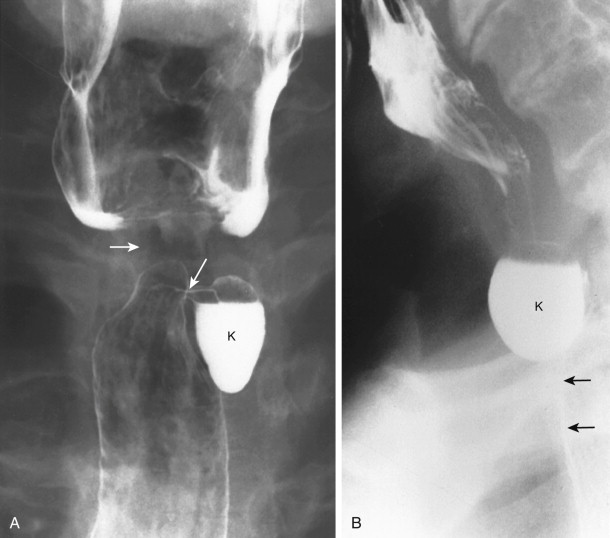

During swallowing, Zenker’s diverticulum appears as a posterior bulging of the lowermost hypopharyngeal wall above an anteriorly protruding pharyngoesophageal segment (cricopharyngeal muscle; Fig. 16-4 ). The neck of the Zenker’s diverticulum can be very broad during swallowing. At rest, the barium-filled diverticulum extends below the level of the cricopharyngeal muscle posterior to the proximal cervical esophagus ( Fig. 16-5 ). After swallowing, barium in the diverticulum is regurgitated into the hypopharynx. In some patients, this regurgitation of barium results in overflow aspiration.

A true Zenker’s diverticulum may be confused with barium trapped above a cricopharyngeal muscle that has closed before the pharyngeal contraction wave has passed. This barium, trapped between downwardly progressing pharyngeal contraction and the cricopharyngeal muscle, is termed a pseudo-Zenker’s diverticulum ( Fig. 16-6 ). Barium may also be trapped above early closure of the upper cervical esophagus. Incomplete opening and early closure of the cricopharyngeal muscle, and early closure of the upper cervical esophagus, have been associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease.

The complications of Zenker’s diverticulum include bronchitis, bronchiectasis, lung abscess, diverticulitis, ulceration, fistula formation, and carcinoma. Any change in the character of dysphagia or bloody discharge in a patient known to have Zenker’s diverticulum should suggest a complication. On barium studies, irregularity of the contour of Zenker’s diverticulum should suggest an inflammatory or neoplastic complication. Carcinoma arises in less than 1% of patients with Zenker’s diverticulum, but it is usually fatal.

Lateral Cervical Esophageal Pouches and Diverticula

The Killian-Jamieson space is a triangular area of weakness in the cervical esophagus just below the cricopharyngeal muscle. This space is bounded superiorly by the inferior margin of the cricopharyngeal muscle, anteriorly by the inferior margin of the cricoid cartilage, and inferomedially by the suspensory ligament of the esophagus originating from the posterior wall of the cricoid cartilage, just before the tendon forms the longitudinal muscle of the esophagus.

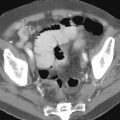

Transient or persistent protrusions of the anterolateral cervical esophagus into the Killian-Jamieson space are termed lateral cervical esophageal pouches or diverticula, respectively. They are also known as Killian-Jamieson pouches or Killian-Jamieson diverticula . Most patients with Killian-Jamieson diverticula are asymptomatic, but some may complain of dysphagia or regurgitation.

These pouches and diverticula are relatively common and may be confused radiographically with Zenker’s diverticulum. Killian-Jamieson diverticula can be bilateral or unilateral. If unilateral, the diverticula are usually found on the left side of the proximal cervical esophagus. Radiographically, a small (3-20 mm in diameter), round to ovoid, smooth-surfaced outpouching is seen just below the level of the cricopharyngeal muscle ( Fig. 16-7 ). On frontal views, pouches appear as small, round, or ovoid protrusions of the lateral upper esophageal wall that are filled late during swallowing and that empty after swallowing. Diverticula appear on frontal views as saccular protrusions that have narrow necks (see Fig. 16-7 ) and do not empty as quickly after swallowing. On lateral views, the anterior wall of the sac is anterior to the cervical esophagus, below the level of the cricopharyngeal muscle. In contrast, the neck of Zenker’s diverticulum is on the posterior hypopharyngeal wall, and the sac extends inferiorly behind the cervical esophagus.

Pharyngeal and Cervical Esophageal Webs

Webs are thin mucosal folds usually located along the anterior wall of the lower hypopharynx and proximal cervical esophagus. They are usually composed of normal epithelium and lamina propria. Some webs show inflammatory changes.

The cause and clinical significance of webs are controversial. Most patients with cervical esophageal webs are asymptomatic. The webs are seen as isolated findings in 3% to 8% of patients undergoing upper GI barium studies. In one autopsy series, 16% of patients had incidental cervical esophageal webs.

Some pharyngeal and cervical esophageal webs are associated with diseases that cause inflammation and scarring, such as epidermolysis bullosa or benign mucous membrane pemphigoid. Several older northern European series showed an association of cervical esophageal webs, iron deficiency anemia, and pharyngeal or esophageal carcinoma. This association was termed Plummer-Vinson syndrome or Paterson-Kelly syndrome. In the United States, no strong association of cervical esophageal webs, iron deficiency anemia, and pharyngoesophageal carcinoma has been found. Webs in the distal esophagus have been associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Some cervical esophageal webs may also be associated with gastroesophageal reflux.

Some webs are present in the valleculae or lower piriform sinus. These vallecular and piriform sinus webs are composed of mucosa, lamina propria, and underlying blood vessels. These webs are thought to be normal variants in the valleculae and piriform sinuses.

Webs appear radiographically as 1- to 2-mm wide, shelflike filling defects along the anterior wall of the hypopharynx or cervical esophagus ( Fig. 16-8 ). The webs protrude to various depths into the esophageal lumen. Webs may extend laterally, and a few extend circumferentially. Circumferential webs appear as ringlike shelves in the cervical esophagus. With severe luminal narrowing, dysphagia may result, especially in patients with circumferential cervical esophageal webs. Partial obstruction is suggested by a jet phenomenon or by dilation of the esophagus or pharynx proximal to the web (see Fig. 16-10 ). A dynamic examination reveals a higher percentage of webs than spot images alone. Better demonstration of webs is also achieved with the use of large boluses of barium.

Webs may be confused radiographically with redundant mucosa in the anterior wall of the pharyngoesophageal segment at the level of the cricoid cartilage. This redundant mucosa has been termed the postcricoid defect and was previously attributed to a venous plexus in this region. However, the postcricoid defect is probably related to redundancy of the mucosal and submucosal tissue in this area. Webs also should not be confused with a prominent cricopharyngeal muscle, which appears as a round, broad-based protrusion from the posterior pharyngeal wall at the level of the pharyngoesophageal segment.

Inflammatory Lesions of the Pharynx

Although acute epiglottitis usually affects children between 3 and 6 years of age, it occasionally causes severe stridor and sore throat in adults. Plain radiographic diagnosis of acute epiglottitis is important (even in adults) because manipulation of the tongue or pharynx may exacerbate edema and respiratory distress. Neck radiographs may show smooth enlargement of the epiglottis and aryepiglottic folds. Barium studies are contraindicated because they may exacerbate edema, triggering an episode of acute respiratory arrest.

Barium studies of the pharynx are usually of limited value in patients with acute sore throat caused by viral, bacterial, or fungal infection. Such patients usually demonstrate normal findings on pharyngograms or evidence of nonspecific lymphoid hyperplasia of the palatine or lingual tonsils.

In immunosuppressed patients with acute dysphagia, barium studies are directed toward the esophagus to demonstrate the presence, site, and type of esophagitis. However, double-contrast examination of the pharynx may demonstrate the plaques of Candida pharyngitis or the ulcers of herpes pharyngitis, particularly in patients with AIDS ( Fig. 16-9 ).

In patients with chronic sore throat, barium studies may help determine whether underlying gastroesophageal reflux and reflux esophagitis are present. Inflammatory disorders of the pharynx or gastroesophageal reflux can alter pharyngeal elevation, epiglottic tilt, or closure of the vocal cords and laryngeal vestibule. Inflammation-induced dysmotility may result in laryngeal penetration and stasis.

Some diseases with diffuse mucous membrane ulceration affect the pharynx. Pharyngeal inflammation and ulceration may be seen in patients with Behçet’s syndrome, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, Reiter’s syndrome, epidermolysis bullosa, or bullous pemphigoid. Most of these patients have recurrent aphthous stomatitis and oropharyngeal ulceration. With severe ulceration, amputation of the uvula and tip of the epiglottis may be observed radiographically. Scarring may cause distortion of the pharyngeal contours. Severe ulceration with subsequent scarring may also be caused by lye ingestion ( Fig. 16-10 ).

Lymphoid Hyperplasia of the Lingual and Palatine Tonsils

The lingual tonsil is an aggregate of 30 to 100 follicles along the pharyngeal surface of the tongue, extending from the circumvallate papillae to the root of the epiglottis. This lymphoid tissue causes the normal surface of the base of the tongue to be divided into small nodules of varying size.

Hypertrophy of the lingual tonsil frequently occurs after puberty, as a compensatory response after tonsillectomy, or as a nonspecific response to allergies or repeated infection. Symptoms attributed to lymphoid hyperplasia of the lingual tonsil include throat discomfort, a globus sensation, and dysphagia. There are no criteria based on size for differentiating nodularity of the base of the tongue because of normal lingual tonsils from that resulting from reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. On frontal radiographs obtained in patients with lymphoid hyperplasia, multiple smooth, round, or ovoid nodules are symmetrically distributed over the surface of the base of the tongue ( Fig. 16-11 ). On lateral radiographs, the base of the tongue may seem to protrude posteriorly. In lymphoid hyperplasia of the palatine tonsils, masslike enlargement of the palatine tonsils is seen in the frontal and lateral views ( Fig. 16-12 ). With severe lymphoid hyperplasia of the base of the tongue, the nodules may extend into the valleculae, along the lingual surface of the epiglottis, or even into the upper hypopharynx. Lingual tonsil lymphoid hyperplasia can be coarsely nodular, asymmetrically distributed, or masslike. However, any asymmetrically distributed coarse nodularity or mass must be viewed with suspicion. The use of endoscopy and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may help exclude malignancy.

Benign Tumors of the Pharynx

A wide variety of benign tumors occur in the pharynx. Nonepithelial tumors arising from the supporting tissues of the pharynx are rare. However, tumor-like cysts of various histologic types are not uncommonly seen in the pharynx. The most common benign lesions are retention cysts of the valleculae or aryepiglottic folds.

Symptoms are related primarily to the location and polypoid or sessile nature of the lesion. Patients with benign tumors of the base of the tongue may be asymptomatic or may complain of throat irritation or dysphagia. Aryepiglottic fold nodules or mass lesions may cause dysphonia or respiratory symptoms such as stridor. Tumors of the epiglottis and aryepiglottic folds may also result in dysphagia, coughing, or choking because of laryngeal penetration. Rarely, pedunculated lesions (e.g., papillomas, lipomas, fibrovascular polyps) may be coughed up into the mouth or may cause sudden death through asphyxiation.

Tumors of various histologic types tend to occur at specific locations in the pharynx. Retention cysts and granular cell tumors are the most common benign tumors of the base of the tongue ( Fig. 16-13 ). Ectopic thyroid tissue and thyroglossal duct cysts may occur at the tongue base but are rare. The tumor-like lesions that usually involve the aryepiglottic folds are retention cysts and saccular cysts. Retention cysts of the aryepiglottic folds are lined by squamous epithelium and filled with desquamated squamous debris ( Fig. 16-14 ). In contrast, saccular cysts of the aryepiglottic folds arise from the mucus-secreting glands of the appendix of the laryngeal ventricle and are filled with mucoid secretions. True soft tissue tumors of the aryepiglottic folds, such as lipomas, neurofibromas, hamartomas, granular cell tumors, and oncocytomas, are rare. Laryngeal involvement in neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen’s disease) is rare but usually involves the region of the arytenoid cartilage and aryepiglottic folds. Benign tumors arising from the minor mucoserous salivary glands are usually seen in the oropharynx in the region of the soft palate and base of the tongue. Benign cartilaginous tumors involving the pharynx (chondromas) usually arise from the posterior lamina of the cricoid cartilage.

Regardless of its underlying histologic characteristics, a benign pharyngeal tumor usually appears radiographically as a smooth, round, sharply circumscribed mass en face and as a hemispheric line with abrupt angulation in profile (see Figs. 16-16 and 16-17 ). Only rarely is a pedunculated polypoid lesion (e.g., papilloma, fibrovascular polyp) seen. The benign nature of these lesions should be confirmed by endoscopic examination. However, submucosal masses are sometimes missed at endoscopy.

Malignant Tumors of the Pharynx

Radiologists should be as familiar with pharyngeal carcinoma as they are with esophageal carcinoma. Squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck (e.g., tongue, pharynx, larynx) constitute 5% of all cancers in the United States, whereas esophageal carcinomas constitute only 1% of all cancers. The radiologist may be the first physician to suggest a diagnosis of pharyngeal carcinoma ( Fig. 16-15 ). Some tumors may be detected during barium studies performed for other reasons. Patients with pharyngeal symptoms or a palpable neck mass may undergo pharyngoesophagography as the initial diagnostic examination. In patients with known pharyngeal cancer, a contrast examination is of value to assist in planning proper work-up and therapy. A barium examination can also be used to rule out a second primary lesion in the esophagus. Furthermore, the examination can detect coexisting structural lesions (e.g., prominent cricopharyngeal muscle, Zenker’s diverticulum, web, stricture) that may be difficult to circumvent safely at endoscopy. Barium studies reveal the size, extent, and inferior limit of pharyngeal tumors and the degree of functional impairment. The barium examination can also show areas behind bulky tumors that are difficult to visualize by endoscopic examination.

Barium studies allow detection of more than 95% of structural lesions below the pharyngoesophageal fold. These studies are especially valuable in areas of the pharynx that are difficult to evaluate by endoscopy (e.g., lower base of the tongue, valleculae, lower hypopharynx, pharyngoesophageal segment).

Signs and Symptoms

The symptoms of pharyngeal carcinoma are nonspecific and usually of short duration (<4 months). They include sore throat, dysphagia, and odynophagia. Choking or coughing may be caused by laryngeal penetration during swallowing or aspiration of barium trapped in ulcerated tumors. Hoarseness occurs primarily in patients with laryngeal carcinoma, supraglottic carcinoma, or carcinoma of the medial piriform sinus infiltrating the arytenoid cartilage or cricoarytenoid joint. A referred earache may occur, especially when nasopharyngeal tumors block the eustachian tube. Some patients are asymptomatic but present with a palpable neck mass. Most patients with squamous cell carcinoma are 50 to 70 years of age. Almost all patients (>95%) are moderate to heavy abusers of alcohol and tobacco or have a tumor related to herpes virus.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Pathology

Squamous cell carcinomas represent 90% of malignant lesions involving the oropharynx and hypopharynx. Most of these tumors are keratinizing squamous cell carcinomas. In general, they occur in two macroscopic forms: (1) exophytic tumors that spread over the mucosa; and (2) infiltrative or ulcerative tumors that penetrate deeply into surrounding soft tissue, cartilage, and bone. Multiple primary lesions of the oral cavity, pharynx, esophagus, and lung are seen in more than 20% of patients. Because such a strong association exists between head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and esophageal carcinoma, a major goal of a preoperative radiologic study is to rule out a synchronous primary esophageal cancer. Between 1% and 15% of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma subsequently develop squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus.

Radiographic Findings

The radiographic findings of pharyngeal cancer include an intraluminal mass, mucosal irregularity, and impairment or loss of normal mobility or distensibility ( Fig. 16-16 ). An intraluminal mass may be manifested radiographically by obliteration of the normal luminal contour, extra barium-coated lines protruding into the expected pharyngeal air column, a focal area of increased radiopacity, or a filling defect in the barium pool. Mucosal irregularity may be seen as abnormal barium collections resulting from surface ulceration or as a lobulated, finely nodular, or granular surface texture. Asymmetrical distensibility is seen as flattening of the pharyngeal contour caused by fixation of structures by infiltrating tumor or by an extrinsic mass impinging on the pharynx.

Cross-sectional imaging studies are the examinations of choice for showing spread of tumor into the submucosa, intrinsic muscles, tissues extrinsic to the pharynx, and regional lymph nodes. Computed tomography (CT) and MRI may occasionally reveal lesions (typically submucosal masses) that are not visible, even with modern endoscopes.

Specific Sites

Nasopharynx.

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common histologic type of nasopharyngeal malignant tumor. Many nasopharyngeal squamous cell cancers are undifferentiated tumors, and many have a reactive lymphoid stroma. The risk factors, age of presentation, and histologic type are more varied than those of the typical squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx and hypopharynx. In addition to alcohol and smoking abuse, poor ventilation, nasal balms, ingested carcinogens, and upper respiratory viruses such as the Epstein-Barr virus have been implicated as causative factors.

Nasopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma occurs at a relatively young age, with 20% of patients being younger than 30 years. Approximately 50% of patients complain of hearing loss because of eustachian tube involvement. About 50% of these patients are asymptomatic and present with a neck mass caused by cervical nodal metastases. Other signs and symptoms include nasal obstruction, epistaxis, pain, headache, and damage to the fifth cranial nerve. The 5-year survival rate varies from 76% for patients with localized tumors to 10% to 20% for patients with cervical lymph node metastases.

MRI is the method of choice for evaluating tumors of the nasopharynx. The radiologist carefully searches for spread to the nasal cavity, sinuses, and cranial base, especially for cranial nerve involvement. Barium studies are used primarily to evaluate the symptoms of nasal regurgitation and voice changes caused by soft palate insufficiency and to rule out a synchronous esophageal tumor.

Palatine Tonsil.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the palatine tonsil is the most common malignant tumor arising in the pharynx. Well-differentiated tumors are usually exophytic and easily seen on barium studies ( Fig. 16-17 ). Poorly differentiated tumors are frequently of the ulcerative infiltrative type and may be obscured on barium studies by the underlying nodular lymphoid tissue of the palatine tonsil. Tonsillar tumors may spread to the soft palate, base of the tongue, and posterior pharyngeal wall. Approximately 50% of patients develop cervical nodal metastases.

Base of the Tongue.

Squamous cell carcinomas of the base of the tongue are poorly differentiated lesions that often present as advanced lesions with nodal metastases. These tumors infiltrate deeply into the intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the tongue. Lymph node metastases are seen ipsilaterally or contralaterally in more than 70% of patients. The 5-year survival rate is 20% to 40%. Patients with small lesions are often asymptomatic but present with enlarged cervical nodes. Initial results of diagnostic endoscopy may be negative. Small or predominantly submucosal lesions may be hidden in the valleculae or the recess between the tongue and tonsil (glossotonsillar recess). Barium, MRI, or CT studies may be extremely helpful in detecting clinically occult lesions with nodal metastases.

Radiographically, an exophytic lesion appears as a polypoid mass projecting into the oropharyngeal air space. An ulcerated lesion appears as an irregular barium collection disrupting the expected contour of the base of the tongue. Nodules of tumor may spread to the palatine tonsil, valleculae, or pharyngoepiglottic fold. Occasionally, a deeply infiltrating, primarily submucosal lesion may be manifested by subtle asymmetric enlargement of the tongue base. A small plaquelike or ulcerative lesion can easily be missed on barium or endoscopic studies but can be detected on MRI or CT studies.

Supraglottic Region.

Squamous cell carcinomas that affect the epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, mucosa overlying the arytenoid cartilages, false vocal cords, and laryngeal ventricles are defined as supraglottic carcinomas. These poorly differentiated or undifferentiated tumors spread rapidly to the entire supraglottic region and pre-epiglottic space. Exophytic lesions are more common ( Fig. 16-18 ). Ulcerative lesions may deeply penetrate the tongue and valleculae and invade the pre-epiglottic space ( Fig. 16-19 ). These tumors may spread laterally to the pharyngoepiglottic folds and lateral pharyngeal walls. Only rarely do these tumors extend through the laryngeal ventricles into the true vocal cords. Cervical nodal metastases are seen in one third to one half of patients. The 5-year survival rate is approximately 40%.