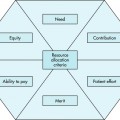

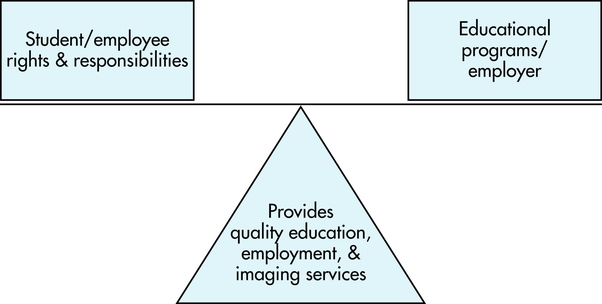

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to perform the following: • Compare and contrast the relationship between the imaging student’s and the imaging professional’s rights, responsibilities, and ethics, including the following considerations: • Ethical theories, and models • Truthfulness and confidentiality • Identify the legal doctrines affecting the relationship between the student and the education program and the imaging employee and employer. • State the origin of due process. • Define substantive and procedural due process. • Explain why accrediting organizations may also impose due process requirements on educational programs. • List the obligations of educational programs regarding restriction of student rights. • Identify the procedural due process protections available when substantive rights are restricted. • State the serious nature of whistleblowing and what to consider before doing so. • Explain the option of carrying personal malpractice insurance. Both imaging programs and students have concerns about student rights. Imaging employers and professionals have continuing concerns about the issue of rights. In each imaging setting both parties involved have ethical obligations to each other; these obligations may extend to the relationships among students, imaging professionals, and others in the medical imaging environment. The correct balance of the rights, responsibilities, and obligations between students and educational programs, as well as the rights, responsibilities, and obligations between imaging professionals and their employers, provides high-quality educational programs, high-quality employment opportunities, and high-quality imaging services (Figure 8-1). This chapter discusses these issues and provides examples of ethical dilemmas concerning rights and responsibilities that students and imaging professionals may encounter during education and employment. The three ethical theories discussed in Chapter 1—consequentialism, deontology, and virtue ethics—serve as guidelines for ethical problem solving both for educational programs and imaging students and for imaging employers and imaging professionals. The choice of theory determines the basis on which each participant interacts within the educational and imaging environment (Table 8-1). TABLE 8-1 ETHICAL THEORIES IN RELATIONSHIP TO STUDENT RIGHTS Although ethical theories provide a foundation for solving problems concerning students’ and employees’ rights and responsibilities, the model of care employed also helps define the ethical structure within which decisions are made (Figure 8-2). The model chosen—engineering, priestly, collegial, contractual, or covenantal—determines the ways in which interactions take place between students and educational programs or employers and employees. (See Chapter 1 for a more thorough discussion of these models.) Students and imaging professionals who feel as though they have lost their identity within the educational and imaging process may be working within the engineering model. An instructor or physician who displays a godlike or fatherly attitude toward students or employees may be employing the priestly, or paternal, model. A cooperative effort between students and teaching programs or imaging professionals and patients is evidence of the collegial model. When students enter an educational program, they enter into a businesslike arrangement that defines the relationship between the student and the program. Rights and responsibilities may be defined within this arrangement. Imaging professionals enter into an employment agreement with an institution or organization in a similar fashion. These are examples of the contractual model. After the contract, including aspects affecting student or employee rights, has been agreed to by both parties, an understanding based on traditional values and goals develops between the student and the program or the employer and employee (see also contract law later in the chapter). This understanding is a crucial element of the covenantal model, which is based on trust and shared experiences within the educational program or the imaging environment. The model most often employed in imaging education and the imaging department is a combination of the contractual and covenantal models. A good example of this combined approach within the radiologic sciences is the learning contract in clinical education.1 An example of this in the imaging employment area is a contract signed by an imaging professional for tuition reimbursement. As a result of the explosion in technology and the ever-increasing knowledge base required for clinical practice, programs are having difficulty providing students with all they need to know to function competently in a continually changing work environment. To facilitate the adequate education of students and prepare them for employment in the evolving health care system, educational programs have developed learning contracts, which are formalized and mutual agreements between instructors and students that guide learning experiences.2 Because they are contracts between programs and students, they require trust. Students enter the program trusting that they will be appropriately prepared to provide high-quality imaging services, and instructors trust that students are adequately motivated to uphold their responsibilities to study and perform their duties. When used properly, learning contracts may be valuable methods to provide needed experiences for students.3 The cost effectiveness of clinical education is often a concern for administrators.4 One of the primary concerns of administrators is whether the value of labor contributed by students offsets the cost of educating them. Indeed, the use of student labor in clinical settings is an ethical concern for educational programs and imaging students contemplating their rights in the educational environment. If students believe they are being used in place of staff radiographers for cost savings to a department, they may question their clinical assignments. Moreover, educators may have difficult ethical decisions to make concerning student rotations if they feel pressured by administrators to provide more student contact hours in the clinical setting. The rights of the students may be endangered if issues of cost savings by staff reduction are contemplated (Box 8-1). Imaging students are responsible for maintaining the safety of their patients and recognizing imaging procedures in which they are competent. When issues of staffing and cost savings clash with student competency and clinical assignments, the student and the educator should be mindful of the accreditation requirements for student supervision set forth by the Joint Review Committee on Education in Radiologic Technology (JRCERT). JRCERT defines direct supervision as student supervision by a qualified practitioner who reviews the procedure in relation to the student’s achievement, evaluates the condition of the patient in relation to the student’s knowledge, is present during the conduct of the procedure, and reviews and approves the procedure or image. Students must be directly supervised until competency is achieved. This supervision ensures patient safety and proper educational practices. JRCERT also states that all repeat radiographs by students will be supervised by a qualified practitioner.5 An emphasis on informed decisions encourages student autonomy by providing the prospective student with important information about the educational program and its policies and procedures. This exchange of information enables the student applicant to make informed decisions concerning participation in the program. After students have chosen and entered their programs, they are typically given a vast amount of information about their future didactic and clinical educational experiences. It is their responsibility to read, digest, and question this information until they have an operative knowledge that will facilitate their educational process. Educators should review this information periodically to ensure that students are provided with current and updated information that will help them obtain the skills and knowledge necessary to become qualified imaging professionals (Box 8-2). A positive environment for imaging education and employment must also encourage justice and fairness (Box 8-3). Justice in imaging educational programs and imaging employment is enhanced through appropriate application of ethical theories and models and the creation of an educational and imaging environment in which student and employee autonomy, informed decisions, truthfulness, and confidentiality are valued.

Student and Employee Rights and Responsibilities

ETHICAL ISSUES

ETHICAL THEORIES

Theory

Example

Consequentialism: the greatest good for the greatest number

Imaging students with the highest grade point averages may be selected to facilitate more educational opportunities for the group as compared to selection of students with lower grades who might require more teacher attention and progress more slowly through modalities, or imaging professionals who learn more quickly may be selected for advancement situations before an equally proficient professional who learns at a slower rate

Deontology: formal rules of right and wrong

Formal rules may serve as a foundation of educational programs and policies or imaging department policies and procedures regarding disciplinary processes and opportunities for students and employees

Virtue ethics: holistic approach to problem solving using practical wisdom

Students and employees may use intellect and practical reasoning when asserting their rights as students or employees in a method useful to themselves and in the educational or employment environment

MODELS

AUTONOMY AND INFORMED DECISIONS

JUSTICE

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Student and Employee Rights and Responsibilities