SYSTEMIC, METABOLIC, AND MISCELLANEOUS DISEASES AFFECTING BONE

KEY POINTS

- Pathology of bone lesions should almost always be read together with the imaging findings to produce the best diagnoses and to optimize medical decision making.

- Often, multifocal or generalized skeletal disease affecting the bones of the head and neck region can sometimes present as an isolated finding or be isolated to the head and neck.

- Manifestations of systemic disease are usually incidental and frequently unimportant in the context of clinical care decisions.

- Osteonecrosis can produce significant pain and functional losses.

- Osteopetrosis and osteogenesis imperfecta may produce significant functional deficits.

HYPERPARATHYROIDISM AND RENAL OSTEODYSTROPHY

Clinical Perspective and Pathophysiology and Patterns of Disease

Primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism will cause bony changes in the facial skeleton and calvarium (Figs. 43.1 and 43.2). In primary disease, there is simply overproduction of parathormone. In secondary disease due to renal failure, multiple mechanisms are at play, including phosphate retention and diminished vitamin D transformation, both of which deplete calcium and lead to overproduction of parathormone.1 This is confounded by the effects of dialysis in some patients, wherein aluminum deposition further impedes proper mineralization of bone. The generalized and sometimes cyclical demineralization (high turnover state) and osteomalacia (lower turnover rate) of the skull and facial bones that may be seen in these disease states can produce a variety of bony changes, including a thickened appearance, especially in a “healed phase,” that can be mistaken for other osteodystrophies or conditions associated with marrow space hyperplasia. Histopathology shows projections of fibrous tissue with osteoclasts at the leading age. The abnormal bone is demineralized and composed of varying size, loosely arranged trabeculae mixed with marrow spaces containing fibrous tissue. Degeneration of fibrous tissue may become cystic and lead to the formation of brown tumors.

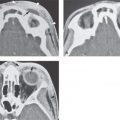

FIGURE 43.1. Computed tomography studies of two patients with brown tumors due to secondary hyperparathyroidism. A–C: Multiple brown tumors in multiple locations throughout the facial bones. There is typical expanded appearance of the involved bones with dehiscence in some locations resulting from regressive remodeling due to the action of activated osteoclasts. D: A different patient with healing of brown tumors in the mandible that are more extensive on the right than the left.

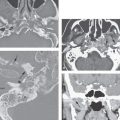

FIGURE 43.2. Computed tomography study of a patient with renal osteodystrophy. A–C: Sclerosis and thickening of involved bone with some degree of obliteration of sinus cavities and marrow spaces of the calvarium and skull base.

In the head and neck region, a coarsened trabecular pattern and a “salt-and-pepper” appearance of bone is expressed most vividly in the calvarium, particularly the skull. Loss of the dental lamina is also are very well known manifestation. The facial skeletal changes associated with hyperparathyroidism are less frequent. All changes vary according to whether the disease is active or healed.

Facial skeletal changes include osteitis fibrosa cystica, a fibrosis dysplasia–like form and a rare form known as uremic leontiasis ossea1–3 Osteitis fibrosa cystica is an active phase finding with peritrabecular fibrosis cystic brown tumors. There is gross thinning multiple bones cortices, coarsened trabeculae, osteolytic lesions, and mixed osteolytic and sclerotic bone that produce the radiographic “salt-and-pepper” appearance of the skull. The fibrous dysplasia–like form is diffuse and generalized rather than localized, like fibrous dysplasia, and is further distinguished by indistinct corticomedullary interfaces. Uremic leontiasis ossea is rare. It is characterized by significant hypertrophy of the jaws with serpiginous channels within the bone and indistinct cortical margins.

Rarely, single or multiple brown tumors presenting in the head and neck region and associated with either primary or secondary hyperthyroidism will be a presenting clinical problem (Fig. 43.1). Multiple brown tumors can present as “cherubism.”

Brown tumors are focal osteolytic, sometimes aggressive-appearing lesions that primarily affect the mandible and maxilla (Fig. 43.1). Cortical penetration may occur. When brown tumors present as a solitary bone lesion, they must be distinguished from giant cell granulomas and giant cell tumors by clinical factors, since pathologically, these three lesions are a mix of proliferating giant cells or osteoclasts in a generally well vascularized background of fibrous tissue discussed in Chapter 41. This histologic similarity accounts for their looking somewhat alike on images.

Imaging Appearance and Differential Diagnosis

The generalized demineralization and osteomalacia of the skull and facial bones that may be seen in these disease states can produce a variety of bony changes described in the previous section. This includes a thickened appearance, especially in a “healed phase,” that can be mistaken for other osteodystrophies or conditions associated with marrow space hyperplasia at first glance. These include fibrous dysplasia and osteopetrosis; however, such changes usually do not occur outside the setting of known renal osteodystrophy.

Brown tumors are “expansile”-appearing lesions of bones with bony margins able to remain mineralized and/or show narrow margins of sharp or indistinct transition depending on the developmental cycle of the metabolic disorder. Soft tissue interfaces generally remain sharp but may be slightly indistinct as well. The extent of bony abnormality is best studied with computed tomography (CT).

The masses may appear solid or “multiloculated” and enhancing internally on both contrast-enhanced CT and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR). Brown tumors should not mineralize unless healing of residual bone is being mistaken for tumor mineralization (Fig. 43.1). Sometimes, fairly diffuse subtle mineralization in a trabecular-type pattern can be seen in the brown tumors as they begin healing.

The internal contents are usually isointense or hypointense to muscle on non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images unless they are hemorrhagic. Brown tumors tend to be between muscle and fat in signal intensity on non–fat-suppressed T2-weighted images because of their fibrous tissue content unless truly cystic change usually related to necrosis or hemorrhage is present. Hemorrhage is a part of the natural history of brown tumors so that blood products, in all phases of evolution, may be visible on MR studies; the appearance of these blood products was discussed in Chapters 10 and 11. If actual fluid levels and an essentially entirely cystic nature are present, those findings suggest but are not specific aneurysmal bone cyst since such regressive changes occur in traumatic bone cysts and brown tumors as well.

Radionuclide scanning will generally show increased uptake and is nondefinitive and cost additive unless one is trying to distinguish solitary from multifocal disease.

Angiography will show these to be vascular blood pool–type lesions and is infrequently performed.

The differential diagnosis of a solitary brown tumor also typically includes several other grossly cystic-appearing bone lesions, including those of dental, osteoid, chondroid, and fibrous origin as well as metastases and the medullary form of plasmacytoma, all of which are discussed in chapters specifically dedicated to those pathologies. If multiple brown tumors are present, the differential diagnosis is not as complicated, although that situation might be mimicked by multiple dentigerous cysts.

PAGET DISEASE

Clinical Perspective, Pathophysiology, and Patterns of Disease

A common disease of uncertain etiology, Paget disease affects the skull in about 25% of patients who have the disease elsewhere. It is a chronic, progressive disorder and is believed to be autosomal dominant or X-linked.4 Recent thought suggests that the paramyxovirus may be an inciting factor. It is a disease essentially of men after the age of 30 years. Secondary sarcoma is possible. The vast majority of head and neck involvement is of the calvarium.

Paget disease has a typically osteolytic wave of activity followed by mineralization of a relatively substandard reparative, largely fibrous matrix. The appearance will then be somewhere between osteolytic and sclerotic depending on when it is imaged in the disease cycle. Paget disease characteristically results in an expanded appearance of any involved bone and a coarsened trabecular pattern.

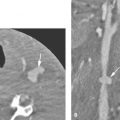

Facial bone and temporal bone involvement is infrequent. Skull base involvement will also include the temporal bone (Fig. 43.3) and can produce basilar invagination and rarely a compressive cranial neuropathy.5

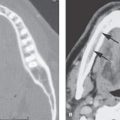

FIGURE 43.3. Computed tomography studies of two patients with Paget disease. A, B: Images show what was relatively localized but bilateral disease of the temporal bone and skull base. There is a mixed lytic and sclerotic pattern that involves the otic capsule and all other bones visible except the ossicles. C, D: A more diffuse case of Paget disease in a relative healing stage, again demonstrating the typical expansile appearance of bone and a mixed lytic and sclerotic pattern. (NOTE:Diffuse or bilateral or multifocal patterns of bone changes in the craniofacial region are usually indicators of this type of pathology or systemic disease.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree