Chapter 7 The admission test by cardiotocography or by auscultation

Since the production of the NICE guidelines13 there has been much discussion about the role of an admission cardiotocograph (CTG). The guidelines suggest that it is not mandatory. This is partly because of the absence of evidence based on randomized controlled trials that it is effective. We hope this chapter will enable caregivers to provide choice to women about this issue.

Fetal morbidity and mortality are greater in high-risk women with hypertension, diabetes, intrauterine growth restriction and other risk factors. A greater number of antenatal deaths are observed in this group. In pregnancies that have proceeded to term, morbidity and mortality due to events in labour occur with similar frequency in those categorized as low risk compared with high risk based on traditional risk classification.56, 57 This may be because high-risk cases such as intrauterine growth restriction have been missed during antenatal care. To resolve this we have to turn our attention to better screening during the antenatal period and at the onset of labour. With traditional assessment the fetal heart is auscultated after admission and every 15 min for a period of 1 min after a contraction in the first stage of labour and every 5 min or after every other contraction in the second stage of labour. During auscultation the baseline fetal heart rate (FHR) can be measured but other features of the FHR such as baseline variability, accelerations and decelerations are more difficult to observe and quantify. Figure 5.28 shows an admission CTG of a fetus in serious trouble with a pathological trace. Auscultation after a contraction by a skilled midwife (indicated by black dots) showed a ‘normal’ heart rate of 150 beats per min (bpm).

Baseline variability is not audible to the unaided ear.

An admission test (AT) should pick up the apparently low-risk woman whose fetus is compromised on admission or is likely to become compromised in labour. This admission test may be performed by a CTG or by ‘intelligent’ auscultation.

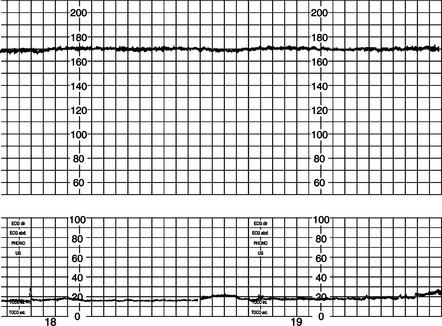

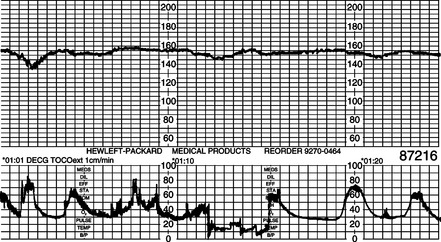

The AT by CTG is a short, continuous electronic FHR recording made immediately on admission, and gives a better impression of the fetal condition compared with simple auscultation. In many hospitals electronic monitoring is performed but it is done long after admission. The mother may have waited for a bed, a nightdress, general observations to be noted and other administrative issues resolved. In most instances the mother walking into the labour ward is entirely healthy and her main concern is to have a healthy baby. An AT may identify those who are already at risk with an ominous pattern on admission even without any contractions (Fig. 7.1). In those with a normal or suspicious FHR the functional stress of the uterine contractions in early labour may bring about the abnormal FHR changes (Fig. 7.2). These changes may be subtle and difficult to identify by auscultation. Careful review may reveal a reduced FSH and a growth-restricted fetus in such cases. An admission CTG can be considered to function in the same way as a natural oxytocin challenge test.

STUDIES ON ADMISSION CARDIOTOCOGRAPHY

In Kandang Kerbau Hospital in Singapore a blinded AT study was carried out on 1041 low-risk women.58 A FHR tracing was obtained after covering the digital display of the FHR and the recording paper and turning down the volume so that the research midwife had no information about what the FHR trace was showing. The transducer was adjusted based on the green signal light of a fetal monitor (Hewlett-Packard 8040 or 8041) which indicates good signal quality and produces a good tracing. The trace, obtained for 20 min immediately on admission, was sealed in an envelope and put aside for later analysis. These women were a low-risk population based on risk factors and hence were sent to the low-risk labour ward for care by intermittent auscultation. This study was accepted by the departmental ethical committee because the normal practice at that time was that none of the low-risk women had any elec-tronic monitoring.

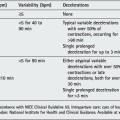

For this study a reactive normal FHR trace was defined as a recording with normal baseline rate and variability, two accelerations of 15 beats above the baseline for 15 s, and no decelerations. A ‘suspicious’ or ‘equivocal’ trace was one that had no accelerations in addition to one abnormal feature such as reduced baseline variability (<5 bpm), presence of decelerations, baseline tachycardia or bradycardia. A trace was classified as ‘ominous’ when more than one abnormal feature or repeated atypical variable or late decelerations were present. To evaluate the outcome, ‘fetal distress’ was considered to be present when ominous FHR changes led to caesarean section or forceps delivery, or if the newborn had an Apgar score <7 at 5 min after spontaneous delivery (Table 7.1).

Table 7.1 Results of admission test in relation to the incidence of ‘fetal distress’

| Admission test | Fetal distress | |

|---|---|---|

| REACTIVE | n = 982 (94.3%) | 13 (1.4%) |

| EQUIVOCAL | n = 49 (4.7%) | 5 (10.0%) |

| OMINOUS | n = 10 (1.0%) | 4 (40.0%) |

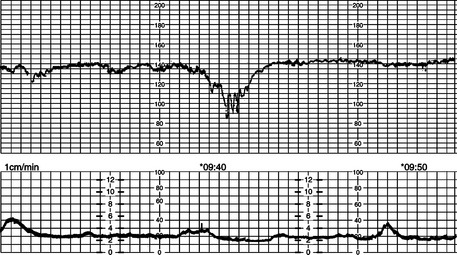

In women with ominous ATs (n = 10), 40% developed fetal distress compared with 1.4% (13 out of 982) in those with a reactive AT. Of those 13 who developed fetal distress after a reactive AT, 10 did so more than 5 h after the AT. Of the 3 who developed fetal distress in less than 5 h, one had cord prolapse (baby born by caesarean section in good condition) and the other 2 fetuses were less than 35 weeks’ gestation. They had low Apgar scores at birth 3 and 4 h after the AT but needed minimal resuscitation. In those with an ominous AT there was 1 fresh stillbirth of a normally-formed baby with normal birth weight for gestational age at term. The midwife was charting the FHR as 140/min every 20 min for 2 h when she reported that she was unable to hear the FHR. The admission test trace is shown in Figure 7.3. There is no doubt that the midwife’s observations were correct; but unfortunately she could not hear the poor baseline variability and the shallow decelerations which are ominous features, although the baseline rate was normal.

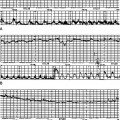

Barring acute events, the AT may be a good predictor of fetal condition at the time of admission and during the next few hours of labour in term fetuses labelled as low risk. If the AT is normal and reactive, gradually-developing hypoxia will be reflected by no accelerations and by a gradually rising baseline FHR; the latter could be picked up at the time of intermittent auscultation or electronic monitoring. Figure 7.4A–F shows sequential changes in an 8-h labour showing gradual rise of FHR with absent accelerations and reduced baseline variability. Furthermore, it is known that if a well-grown fetus with clear amniotic fluid and a reactive trace starts to develop an abnormal FHR pattern, it takes some time with these FHR changes before acidosis develops. It was estimated that in these situations, for 50% of the babies to become acidotic took 115 min with repeated late decelerations, 145 min with repeated variable decelerations and 185 min with a flat trace.15

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree