Knee Checklists

1

1

Radiographic examination

AP

Obliques (internal and external)

Cross-table lateral

Sunrise view of patella

2

2

Hemarthrosis/lipohemarthrosis – distention of suprapatellar bursa

Important clue to

Underlying obscure fractures

Cruciate and collateral ligament and meniscal injuries

Most commonly ACL tear

3

3

Common sites of injury in adults

Patella

Tibial plateau

Distal femur

Metaphysis/intercondylar

Proximal fibula

Head

Neck

Flake/avulsions

Osteochondral fractures

Joint surface patella or femoral condyles

Tibial spine – avulsion ACL

Posterior tibial plateau – avulsion PCL

Segond fracture – lateral tibial plateau just distal to joint line

Sign of ACL tear

Reverse Segond fracture – medial tibial plateau just distal to joint line

Sign of PCL tear

Proximal tip head of fibula – arcuate sign

Sign of injury ligamentous and meniscal structures of the posterolateral corner

4

4

Common sites of injury in children and adolescents

Patella

Anterior tibial tubercle

Anterior tibial spine

Buckle fracture proximal anterior tibial metaphysis

Toddlers’ fracture tibial shaft

Distal femoral and proximal tibial epiphyseal injuries are rare.

5

5

Injuries likely to be missed

Subtle tibial plateau fractures

Often not seen on AP or lateral views

Need oblique views to identify fracture

Fine, linear intraarticular bone fragment indicating osteochondral fracture

Small avulsion fractures about tibial plateau

Segond fracture, etc. (See

3 Flake/avulsions)

3 Flake/avulsions)

6

6

Where else to look when you see something obvious

| Obvious | Look for |

|---|---|

| Tibial spine | ACL avulsion |

| Posterior tibial plateau | PCL avulsion |

| Segond fracture | ACL tear |

| Reverse Segond fracture | PCL tear |

| Proximal tip head of fibula | Injury of the posterolateral comer of the knee |

| Deep notch femoral condyle | ACL tear |

7

7

Where to look when you see nothing at all

If no apparent joint effusion, check for

Fractures of head and neck of fibula

Dislocation/subluxation of proximal tibiofibular joint

If joint effusion present without obvious fracture, consider MRI to

Identify otherwise nonapparent fracture

Tibial spine

Tibial plateaus

Patella

Reveal torn cruciate or collateral ligament and/or meniscal tear

Knee– the Primer

1

1

Radiographic examination

AP

Obliques (internal and external)

Cross-table lateral

Sunrise view of patella

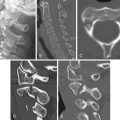

The initial radiographs of the injured knee should include four views: AP, internal and external obliques, and a cross-table (horizontal beam) lateral view ( Figure 10-1 ). AP and lateral views alone are insufficient to exclude subtle, nondisplaced fractures, particularly of the tibial plateaus. If injury to the patella is suspected, a sunrise view of the patella should also be obtained.

2.

2. The AP view ( Figure 10-1 A ) gives an excellent view of the tibial and femoral joint surfaces. The patella is less well seen because of the underlying femur. Most fractures of the femur and proximal tibia are well seen in this projection. The lateral view ( Figure 10-1 B ) gives the best view of the patella and also allows the detection of knee joint effusions, as evidenced by distention of the suprapatellar bursa as shown in section ![]() 2.

2.

The oblique views, internal oblique ( Figure 10-1 C ) and external oblique ( Figure 10-1 D ), demonstrate tibial plateau fractures and less often, patellar fractures that cannot be seen on the AP and lateral views. The sunrise view ( Figure 10-1 E ) shows the joint surface of the patella and provides an orthogonal view of patellar fractures in association with the lateral view. The medial facet of the patella (to the viewer’s left) is shorter and more angulated than the lateral facet (to the viewer’s right).

2

2

Hemarthrosis/lipohemarthrosis – distention of suprapatellar bursa

Important clue to

Underlying obscure fractures

Cruciate and collateral ligament and meniscal injuries

Most commonly ACL tear

The detection of a joint effusion is a valuable finding on radiographs of the traumatized knee because a hemarthrosis points to a substantial intraarticular injury. Conversely, the absence of a joint effusion essentially excludes the presence of a significant intraarticular injury. For trauma the lateral view is best obtained using a horizontal beam with the patient in the supine position. This allows a layering of fluid in the suprapatellar bursa. A fat/fluid level indicates the presence of a lipohemarthrosis, signifying the likelihood of an intraarticular fracture.

The intraarticular injury is either a fracture or a significant injury of the cruciate or collateral ligaments and/or tear of the menisci. If a fluid/fluid level (lipohemarthrosis) is noted, this indicates the presence of an intraarticular fracture involving the joint surface.

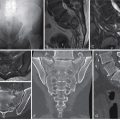

The normal suprapatellar bursa is seen on the lateral view as a line extending obliquely anterior and superior from the superior/posterior surface of the patella to the posterior surface of the quadriceps tendon ( Figure 10-2 A ). The normal width of the bursa is 7 mm or less. Widths of more than 10 mm indicate a significant joint effusion. A small to moderate-sized effusion is shown in Figure 10-2 B . Note that the normal fat density behind the quadriceps tendon is replaced by a soft tissue density arising at the superior posterior surface of the patella. This density is the distended suprapatellar bursa which lies against and silhouettes the quadriceps tendon. A larger effusion is shown in Figure 10-2 C . This almost completely replaces the normal fat density. In Figure 10-2 D the quadriceps tendon is bulged outward by an even larger joint effusion.

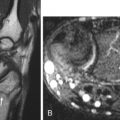

Figures 10-3 A and 10-3 B are horizontal beam cross-table lateral views. In trauma the lateral view is best obtained using a horizontal beam with the patient in the supine position. This allows a layering of fluid in the suprapatellar bursa. A fat/fluid level indicates the presence of a lipohemarthrosis, signifying the likelihood of an intraarticular fracture. Note horizontal layering of the effusion ( Figures 10-3 A and 10-3 B ) with the lucent fat layer seen on top (anteriorly). The presence of intraarticular fat, referred to as lipohemarthrosis, indicates the presence of an intraarticular fracture. If you identify a lipohemarthrosis but see no obvious intraarticular fractures, search for fine, nondisplaced fractures of the joint surfaces especially of the tibial plateaus, patella ( Figure 10-3 A ), and anterior tibial spine ( Figure10-3 B ).

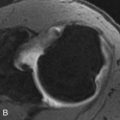

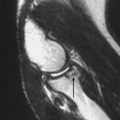

If a knee joint effusion is present, but no fractures are detected ( Figure10-4 A ), the underlying injury must be presumed due to an internal derangement (i.e., a tear of the cruciate or collateral ligaments or meniscal tear). An MRI is warranted to identify the exact source of the hemarthrosis. The most common cause, by far, is a tear of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) as shown by the PD FSE Fat Sat sagittal image ( Figure 10-4 B ).

3

3

Common sites of injury in adults

Patella

Tibial plateau

Distal femur

Metaphysis/intercondylar

Proximal fibula

Head

Neck

Avulsion proximal tip (arcuate sign)

Osteochondral fractures

Joint surface patella or femoral condyles

Flake/avulsions

Tibial spine – avulsion ACL

Posterior tibial plateau – avulsion PCL

Segond fracture – lateral tibial plateau just distal to joint line

Sign of ACL tear

Reverse Segond fracture – medial tibial plateau just distal to joint line

Sign of PCL tear

Proximal tip head of fibula – arcuate sign

Sign of injury ligamentous and meniscal structures of the posterolateral corner

Pattern of search

Diagrams of the knee ( Figure 10-5 ) pinpoint the common sites of fracture in adults. The most common sites of fracture are identified by thicker red lines. Less common sites are designated by fine red lines. Your pattern of search should include all sites.