Chapter 1 The lumbar vertebrae

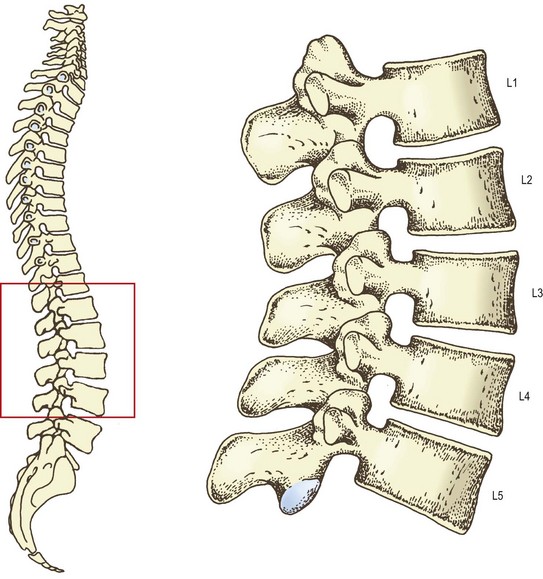

The lumbar vertebral column consists of five separate vertebrae, which are named according to their location in the intact column. From above downwards they are named as the first, second, third, fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae (Fig. 1.1). Although there are certain features that typify each lumbar vertebra, and enable each to be individually identified and numbered, at an early stage of study it is not necessary for students to be able to do so. Indeed, to learn to do so would be impractical, burdensome and educationally unsound. Many of the distinguishing features are better appreciated and more easily understood once the whole structure of the lumbar vertebral column and its mechanics have been studied. To this end, a description of the features of individual lumbar vertebrae is provided in the Appendix and it is recommended that this be studied after Chapter 7.

A typical lumbar vertebra

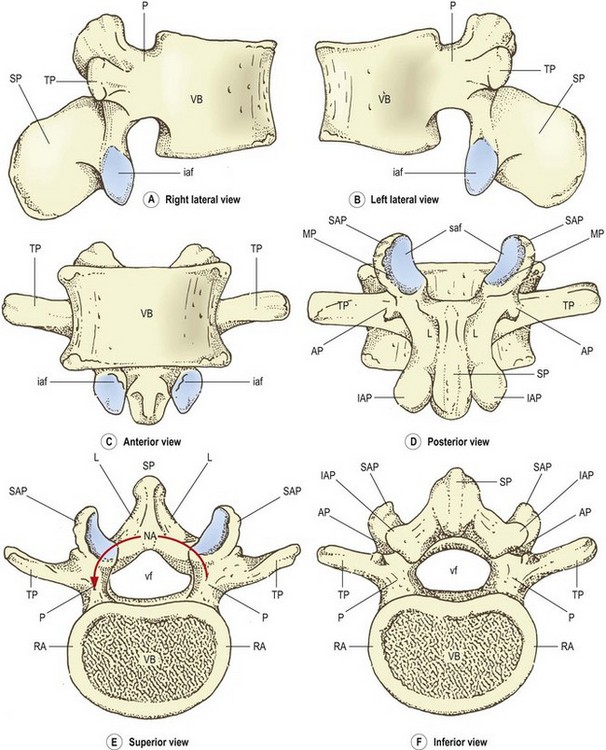

The lumbar vertebrae are irregular bones consisting of various named parts (Fig. 1.2). The anterior part of each vertebra is a large block of bone called the vertebral body. The vertebral body is more or less box shaped, with essentially flat top and bottom surfaces, and slightly concave anterior and lateral surfaces. Viewed from above or below the vertebral body has a curved perimeter that is more or less kidney shaped. The posterior surface of the body is essentially flat but is obscured from thorough inspection by the posterior elements of the vertebra.

The greater part of the top and bottom surfaces of each vertebral body is smooth and perforated by tiny holes. However, the perimeter of each surface is marked by a narrow rim of smoother, less perforated bone, which is slightly raised from the surface. This rim represents the fused ring apophysis, which is a secondary ossification centre of the vertebral body (see Ch. 12).

The posterior surface of the vertebral body is marked by one or more large holes known as the nutrient foramina. These foramina transmit the nutrient arteries of the vertebral body and the basivertebral veins (see Ch. 11). The anterolateral surfaces of the vertebral body are marked by similar but smaller foramina which transmit additional intra-osseous arteries.

Projecting from the back of the vertebral body are two stout pillars of bone. Each of these is called a pedicle. The pedicles attach to the upper part of the back of the vertebral body; this is one feature that allows the superior and inferior aspects of the vertebral body to be identified. To orientate a vertebra correctly, view it from the side. That end of the posterior surface of the body to which the pedicles are more closely attached is the superior end (Fig. 1.2A, B).

The word ‘pedicle’ is derived from the Latin pediculus meaning little foot; the reason for this nomenclature is apparent when the vertebra is viewed from above (Fig. 1.2E). It can be seen that attached to the back of the vertebral body is an arch of bone, the neural arch, so called because it surrounds the neural elements that pass through the vertebral column. The neural arch has several parts and several projections but the pedicles are those parts that look like short legs with which it appears to ‘stand’ on the back of the vertebral body (see Fig. 1.2E), hence the derivation from the Latin.

The full extent of the laminae is seen in a posterior view of the vertebra (Fig. 1.2D). Each lamina has slightly irregular and perhaps sharp superior edges but its lateral edge is rounded and smooth. There is no medial edge of each lamina because the two laminae blend in the midline. Similarly, there is no superior lateral corner of the lamina because in this direction the lamina blends with the pedicle on that side. The inferolateral corner and inferior border of each lamina are extended and enlarged into a specialised mass of bone called the inferior articular process. A similar mass of bone extends upwards from the junction of the lamina with the pedicle, to form the superior articular process.

Extending laterally from the junction of the pedicle and the lamina, on each side, is a flat, rectangular bar of bone called the transverse process, so named because of its transverse orientation. Near its attachment to the pedicle, each transverse process bears on its posterior surface a small, irregular bony prominence called the accessory process. Accessory processes vary in form and size from a simple bump on the back of the transverse process to a more pronounced mass of bone, or a definitive pointed projection of variable length.1,2 Regardless of its actual form, the accessory process is identifiable as the only bony projection from the back of the proximal end of the transverse process. It is most evident if the vertebra is viewed from behind and from below (Fig. 1.2D, F).

Apart from providing this aid in orientating a lumbar vertebra, these notches have no intrinsic significance and have not been given a formal name. However, when consecutive lumbar vertebrae are articulated (see Fig. 1.7), the superior and inferior notches face one another and form most of what is known as the intervertebral foramen, whose anatomy is described in further detail in Chapter 5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree