LEARNING OBJECTIVES

1. Presentation, imaging findings, and potential causes of gynecomastia

2. Risk factors for breast cancer in men

3. Imaging findings in men with breast cancer

4. Metastatic disease to the breast in men

Our approach to men presenting with breast-related symptoms includes marking the area of concern with a metallic BB and obtaining craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique views of the symptomatic side. Following review of these images, we may obtain views of the contralateral breast for comparison. If benign changes are diagnosed, no further evaluation is undertaken. Spot compression and spot compression magnification views are obtained as needed for evaluation of findings suggestive of an underlying cancer.

Mammographically, the normal male breast is predominantly fatty with prominent pectoral muscles and a small nipple. Rarely, the sternalis muscle (1,2) may be imaged in men (Fig. 10.1). When present, breast tissue in men is primarily composed of subareolar ducts with no significant branching and sparse surrounding stroma. Lobular units are rare. Consequently, lesions arising in the lobules such as cysts, fibroadenomas, sclerosing adenosis, lobular neoplasia, and invasive lobular carcinoma are rare in men who are not taking exogenous estrogen (e.g., for prostate cancer treatment). All of the breast lesions discussed for women can occur in men, however, with a significantly lower incidence (particularly, as already mentioned, the lobular-derived lesions).

The principles for positioning the male breast are the same as those described for women. The compression paddle used routinely for screening studies can make it difficult for the technologist to hold the male breast in place. Specifically, as compression is applied, the technologist may find it difficult to slide her hand out from under the paddle without scraping her knuckles or letting go of the breast prematurely. Some equipment manufacturers provide a paddle that is half the width (see Fig. 2.2A) of the standard compression paddle for imaging male patients (these paddles are also useful in women who have small breasts or those with implants for the implant-displaced views).

Breast imaging studies in men are scheduled as diagnostics since the patients present with breast-related symptoms. Cooper and associates (3) suggest that mammography is not necessary in men under the age of 50 whom present with diffuse breast enlargement or a palpable non-indurated central subareolar mass unless there are other strong clinical indications such as skin changes or bloody nipple discharge. In their series, none of 43 male patients under age 50 were found to have breast cancer (3). Although there is no significant data supporting screening mammography in men, it may be something to consider in those who have a personal history of breast cancer or in families with male breast cancer and the BRCA2 gene. It is also unknown if screening should be done routinely in transgender (male to female) patients.

GYNECOMASTIA

Gynecomastia is common, reportedly occurring in 57% of men over the age of 44 (4). Gynecomastia is the enlargement of the male breast with secondary branching of the subareolar ducts and proliferation of surrounding stroma. Patients present describing a “lump” behind the nipple; some men describe pain with the lump. Gynecomastia may be uni- or bilateral, symmetric (Fig. 10.2) or asymmetric (Fig. 10.3). Cooper et al. (3) described unilateral involvement in 33% of their patients with gynecomastia and in 33% it was asymmetric. Appelbaum et al. (4) reported 61 patients with gynecomastia, 55 of which had bilateral mammograms: in 84% of the patients the gynecomastia was asymmetric, in 2% it was symmetrical, and in 14% it was unilateral. Increases in serum estradiol levels, combined with decreases in testosterone levels, are thought to be the etiologic factors governing the development of gynecomastia. At this time, there is no known association between gynecomastia and breast cancer in men. Some of the causes of gynecomastia are listed in Table 10.1.

Three patterns have been described for gynecomastia mammographically (3–7). The nodular pattern is characterized by focally increased tissue in the subareolar area (Fig. 10.4) that may fan out symmetrically from the nipple. It has been suggested that this represents the early phase of gynecomastia and corresponds to florid gynecomastia histologically. The epithelial lining of the ducts is hyperplastic and the surrounding stroma is edematous, loose, and cellular. The fibrous or dendritic pattern appears as retroglandular tissue with prominent fibrous extensions that radiate out into the fatty tissue. Histologically, this is fibrous gynecomastia and reflects long-standing changes; there is ductal proliferation with dense fibrotic stroma. Diffuse glandular gynecomastia is the third pattern; it simulates the heterogeneously dense breast in women (Fig. 10.5). Appelbaum et al. (4) describe 61 patients with histologically proven gynecomastia: 77% had nodular, 20% dendritic, and 3% diffuse patterns mammographically. In some men presenting with breast enlargement and tenderness, fatty tissue alone is imaged on the mammogram (Fig. 10.6).

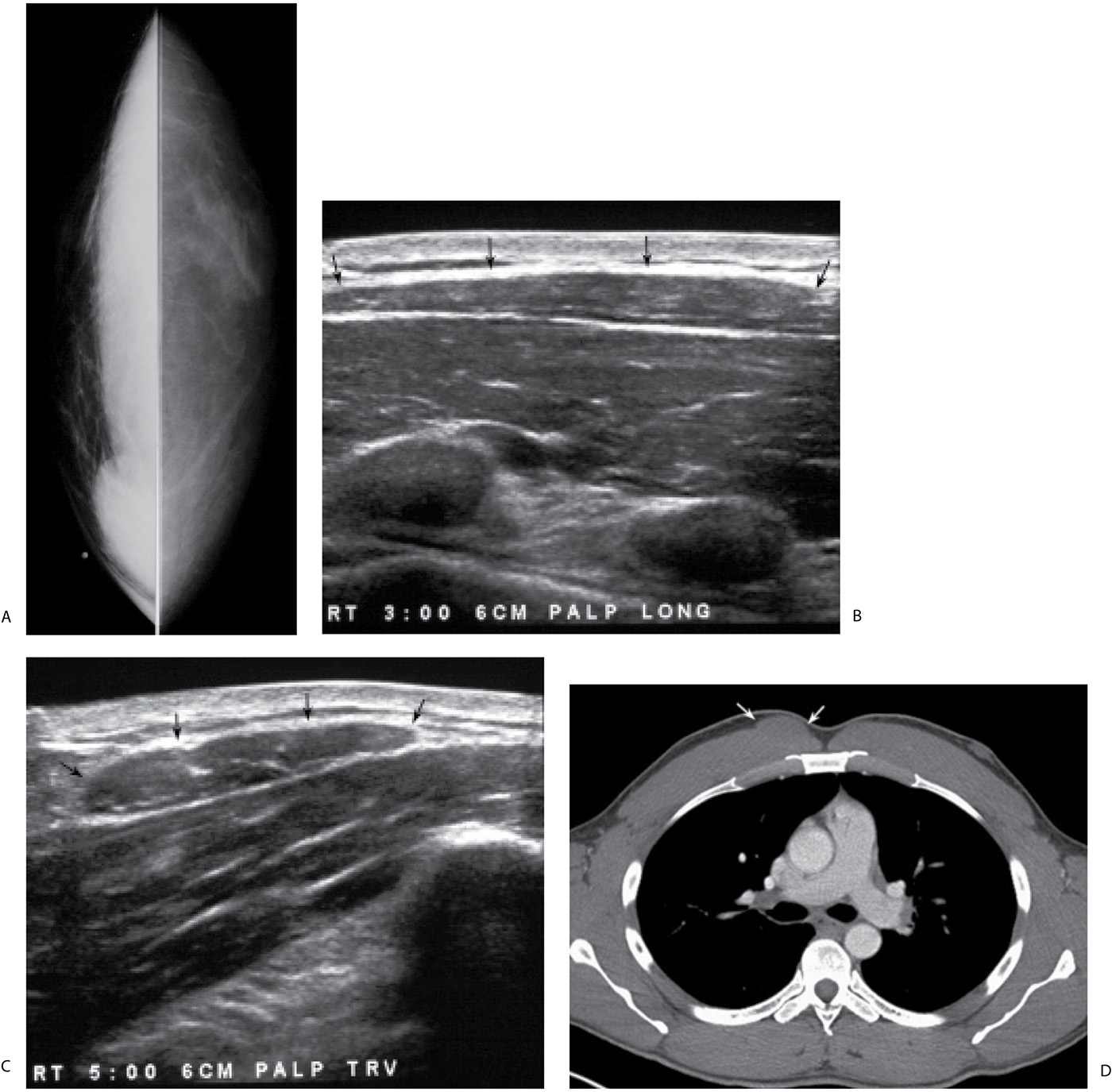

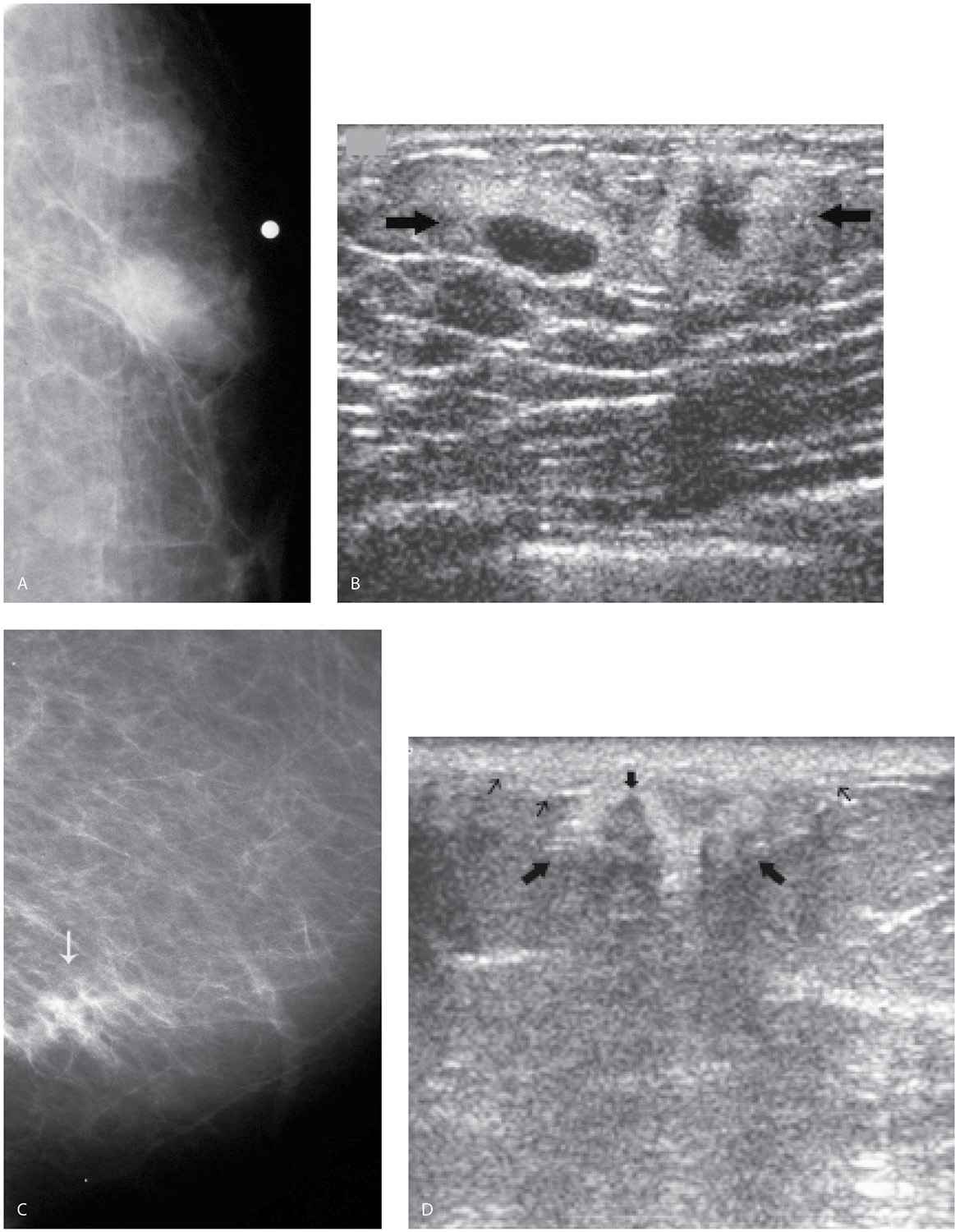

FIG. 10.1 • Sternalis muscle. A: Craniocaudal views in a 33-year-old weightlifter describing a “lump” in the lower inner aspect of the right breast. Metallic BB is used to denote the palpable finding. B: Ultrasound, sagittal plane. On physical examination, the “lump” described by the patient is hard and can be followed in a longitudinal course medially in the right breast close to the sternum. A hypoechoic tubular structure (arrows) is seen in the subcutaneous tissue overlying the deep pectoral fascia. C: Ultrasound, transverse plane. In cross-section, an oblong mass-like structure (arrows) with internal striations is imaged corresponding to the palpable finding described by the patient. A miniscule amount of subcutaneous fat is present interposed between the skin and the palpable finding. Also, note the thickness of the pectoral muscle in this athletic patient. D: CT scan. In cross-section, an oval mass (arrows) is noted superimposed on the right pectoral muscle. This is actually a tubular structure coursing along the anteromedial edge of the pectoral muscle consistent with a sternalis muscle.

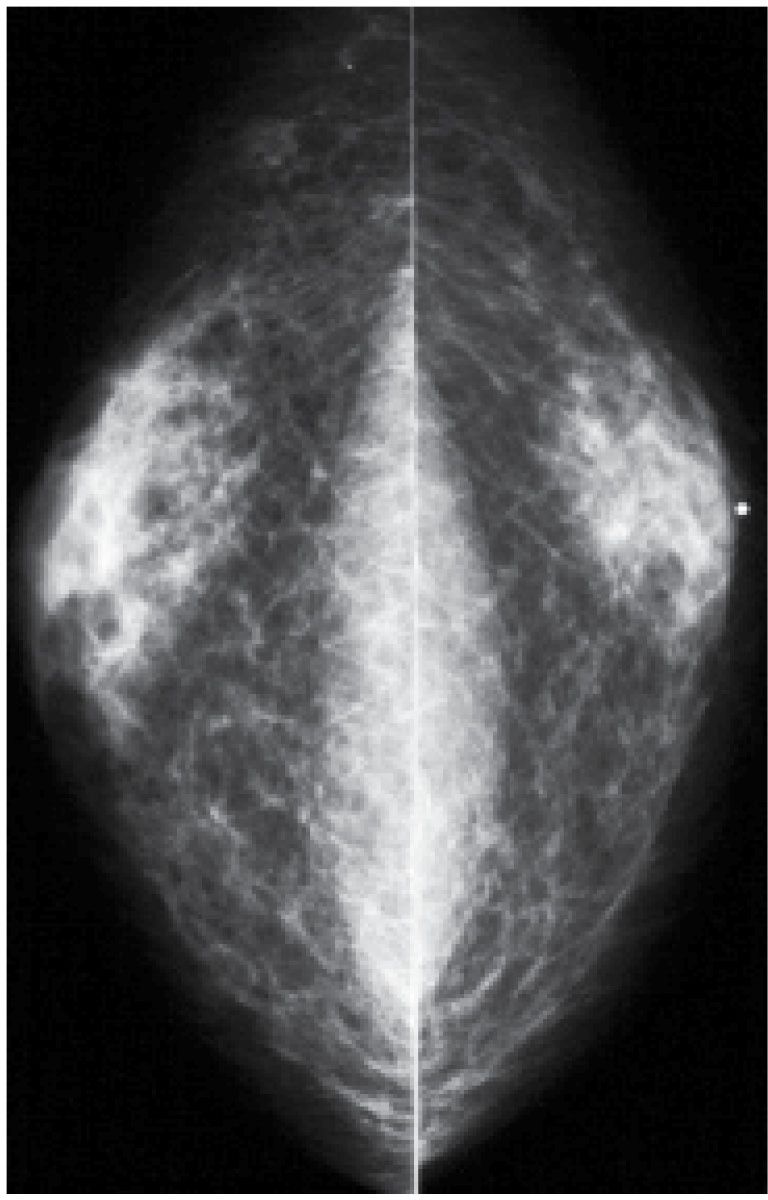

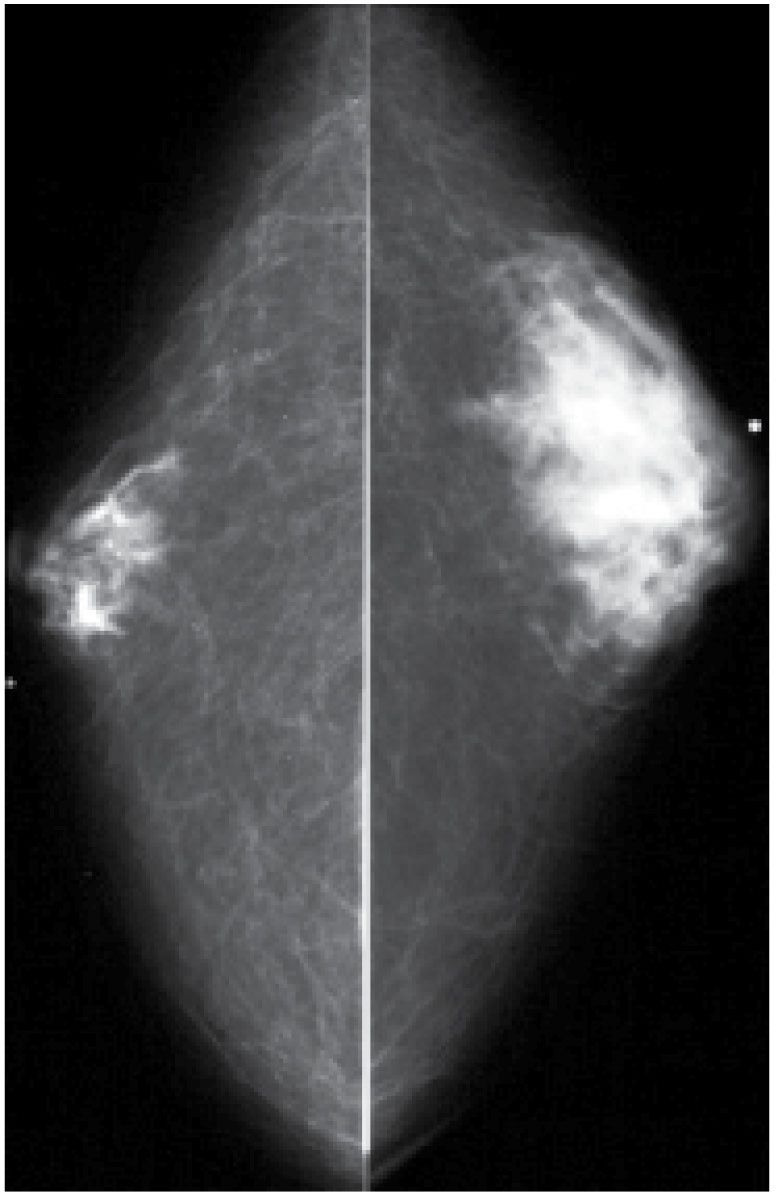

FIG. 10.2 • Gynecomastia, symmetric. Craniocaudal views in a 49-year-old man. Glandular tissue is noted centered on the nipples and fanning out into the surrounding fatty tissue. Metallic BBs (not readily apparent on the right) used to denote palpable finding. BI-RADS 2: Benign finding.

FIG. 10.3 • Gynecomastia, asymmetric. Craniocaudal views in a 61-year-old man. Glandular tissue is present bilaterally; however, it is asymmetric with more tissue seen in the left breast compared with the right. Metallic BBs denoting palpable findings. BI-RADS 2: Benign finding.

Table 10.1 CAUSES OF GYNECOMASTIA

Idiopathic |

Physiologic |

Neonate (placental estrogens) |

Puberty (imbalance in androgen–estrogen ratio) |

Elderly (decreases in plasma testosterone levels) |

Diseases with estrogen excess |

Testicular tumors (Leydig cell, Sertoli cell, testicular germ cell) |

Non-testicular tumors (lung, liver, renal, adrenocortical, hepatocellular) |

Cirrhosis |

Endocrine abnormalities (hypo- or hyperthyroidism) |

Nutritional deprivation |

Androgen deficiency |

Aging |

1° hypogonadism; Klinefelter syndrome (XXY) |

2° hypogonadism (trauma, orchitis, cryptorchidism, irradiation, hydrocele) |

Renal failure (and hemodialysis) |

Drugs |

Estrogenic activity (anabolic steroids, exogenous estrogen—diethylstilbestrol for prostate CA, digitalis, heroin, marijuana, alcohol) |

Inhibition of testosterone action or synthesis (cimetidine, diazepam, phenytoin, spironolactone, vincristine, methotrexate) |

Idiopathic mechanism (furosemide, isoniazid, methyldopa, nifedipine, reserpine, theophylline, verapamil) |

Systemic disorders (unknown mechanism) |

Non-neoplastic diseases of the lung |

Chest wall trauma |

HIV |

On ultrasound, the findings seen with gynecomastia are non-specific. In some patients, normal appearing tissue is imaged corresponding to the palpable abnormality fanning out from under the nipple. In others, the tissue may have an irregular appearance with long hypoechoic spicules possibly leading to confusion regarding the diagnosis (Fig. 10.4B). We do not routinely ultrasound patients in whom the mammographic findings are diagnostic of gynecomastia. Ultrasound is done if the diagnosis of gynecomastia remains in doubt after the mammogram, if there are findings not centered in the subareolar area or a mass is identified mammographically.

The management of gynecomastia is variable. In patients with drug-related gynecomastia, attempts can be made to eliminate the causative agent or, if this is not possible, another drug can be tried. No intervention is indicated unless the symptoms are severe or if the patient is bothered by the changes in the breast. Patients with significant symptoms may undergo surgical excision of the tissue. Unless there is a significant change in the physical findings, no imaging follow-up is recommended. Once it has developed, gynecomastia does not usually resolve particularly if the underlying cause is not identified (e.g., idiopathic).

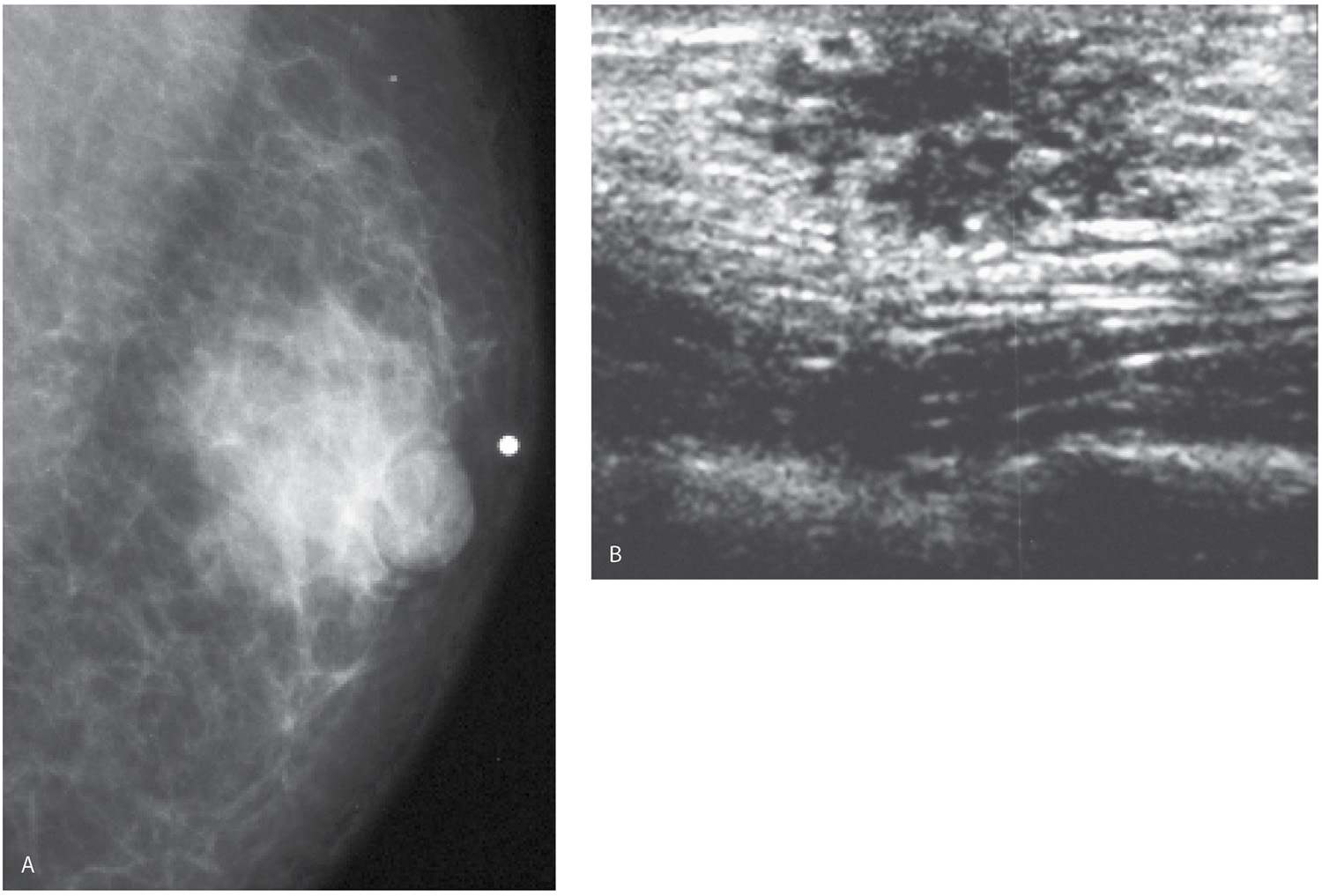

FIG. 10.4 • Gynecomastia, nodular pattern. A: Mediolateral oblique view in a 94-year-old man presenting with a “lump” in the left breast. Metallic BB denotes palpable finding. Round glandular tissue is imaged corresponding to the mass. Scalloping of the density is noted, consistent with tissue. B: Ultrasound. Irregular mass-like area of mixed echogenicity with internal hypoechoic serpiginous tubular-like structures (likely ducts) radiating out symmetrically from the nipple. The irregular spiculated-like appearance of this tissue should not be confused with a mass having spiculated margins. BI-RADS 2: Benign finding. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

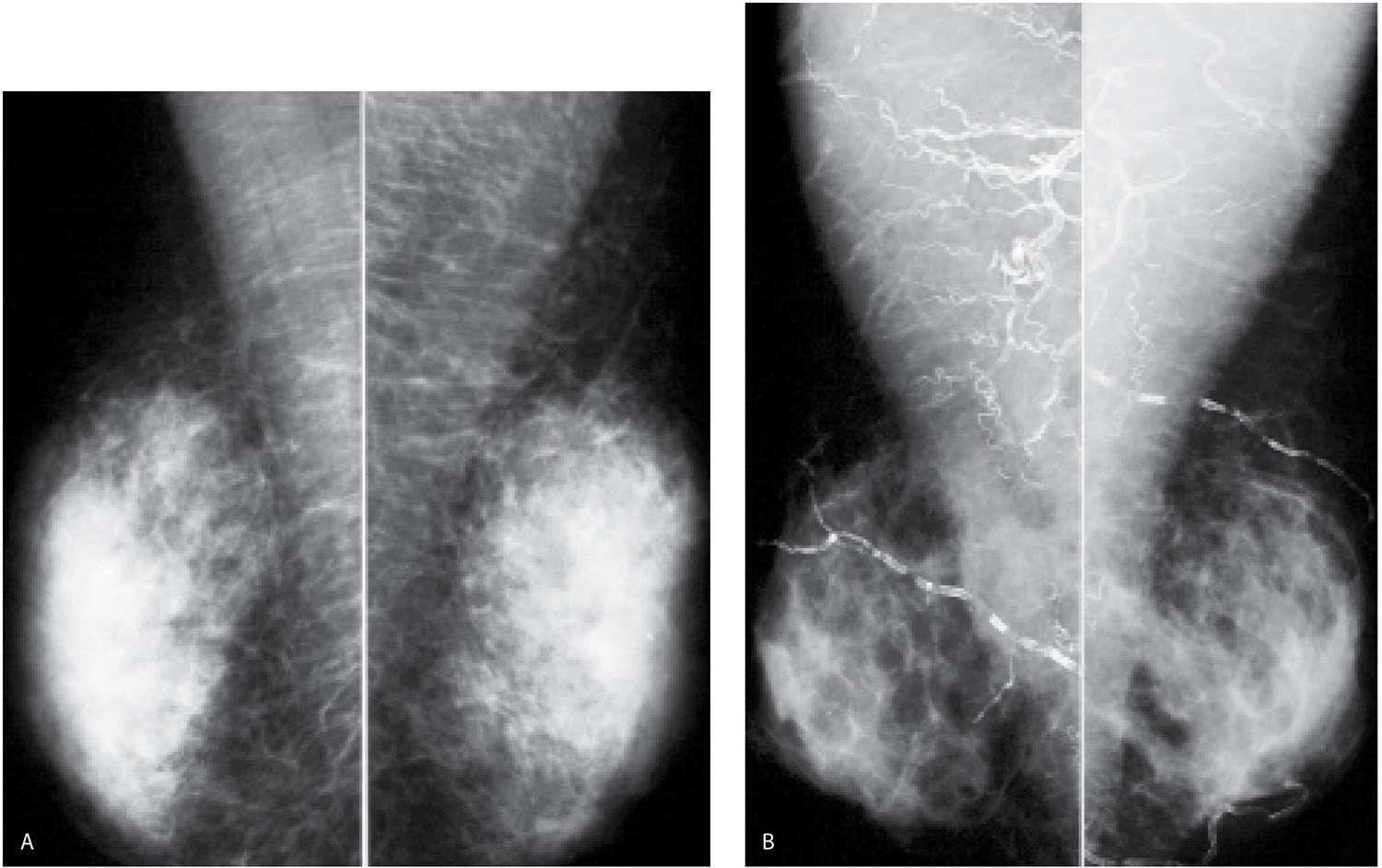

FIG. 10.5 • Gynecomastia, diffuse pattern. A: Mediolateral oblique views in a 35-year-old man. Bilateral symmetrically dense glandular tissue is present. In the absence of an explanation for this amount of gynecomastia in a 35-year-old patient, hormonal and testicular evaluation is indicated. B: Mediolateral oblique views in a 56-year-old man. Bilateral symmetrically dense glandular tissue is present. Extensive calcification of the arteries is noted in a patient with end-stage renal disease and hyperparathyroidism. Also, note prominence of the pectoral muscles.

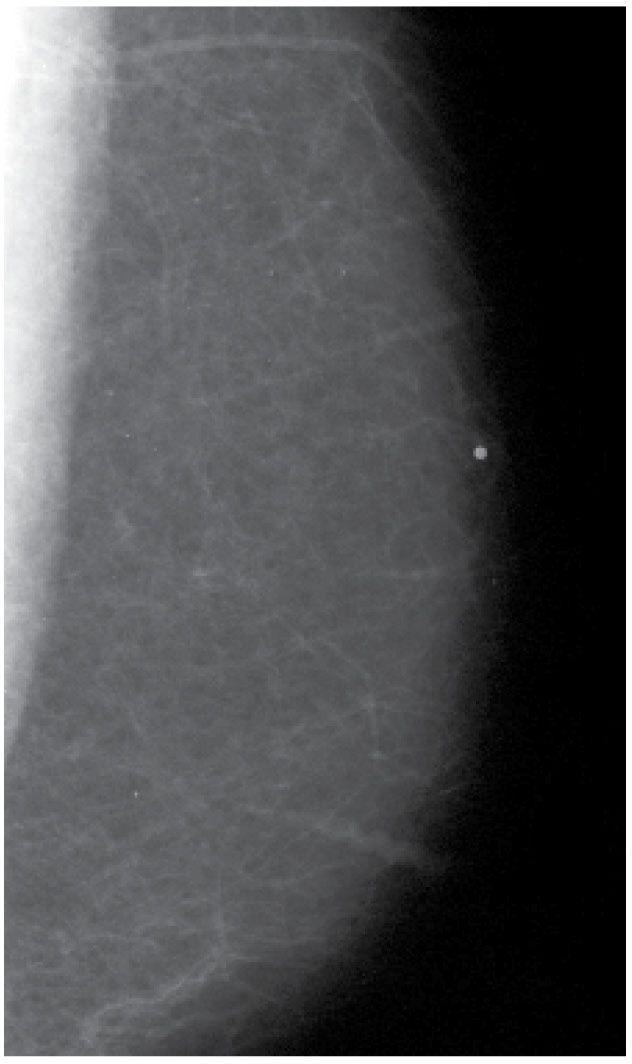

FIG. 10.6 • Fatty tissue. Left mediolateral oblique view. When fatty tissue is imaged corresponding to a palpable finding, it is sometimes called pseudo-gynecomastia. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

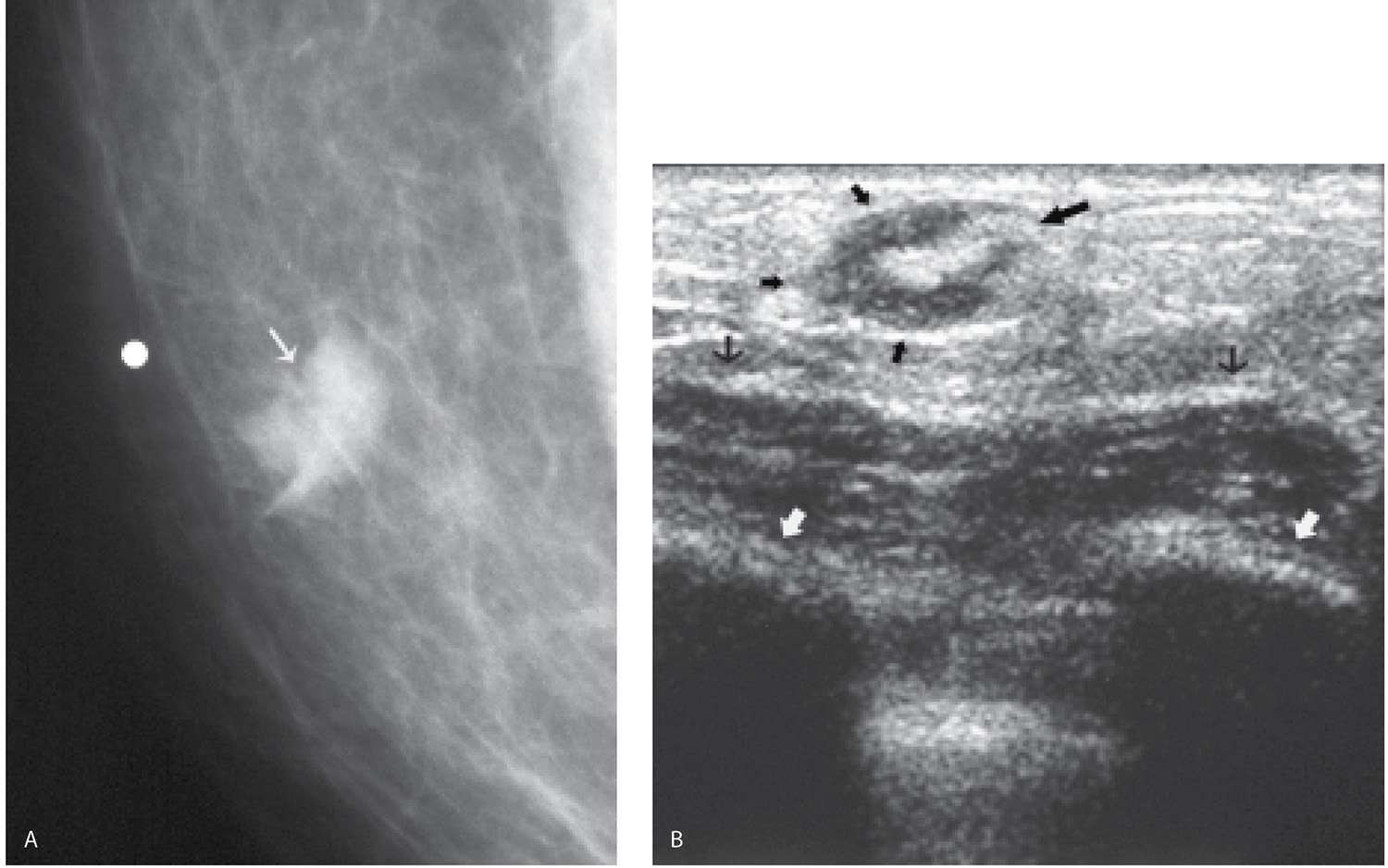

FIG. 10.7 • Intramammary lymph node, medial. A: Spot compression view in a 37-year-old man presenting with a “lump” (arrow). Metallic BB used to denote palpable finding. Mass (arrow) with indistinct margins and the suggestion of a fatty notch is imaged on the spot view. B: Ultrasound. Oval hypoechoic mass (small thick black arrows) with a hyperechoic fatty hilar region (large black arrow) is imaged corresponding to the palpable mass. The ultrasound features are consistent with an intramammary lymph node. Deep pectoral fascia (thin black arrows); ribs (white arrows) with associated shadowing. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

BENIGN LESIONS

Fat-containing masses in men are benign and have appearances similar to those described for women. These include lipomas, lymph nodes (Fig. 10.7), hematomas, and fat necrosis (Fig. 10.8). Water density masses seen in men include epidermal inclusion cysts, abscesses (Fig. 10.9), papillomas, pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (Fig. 10.10), and focal fibrosis (diabetic mastopathy). As mentioned previously, cysts and fibroadenomas as lobular derivatives are not usually seen in men.

BREAST CANCER

Breast cancer in men represents approximately 1% of all breast cancers and 0.2% of all cancers diagnosed in men; breast cancer in men is thought to be unrelated to gynecomastia. It is estimated that 2,360 men will be diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014 and that 430 men will die of breast cancer–related complications (in contrast 232,670 women and 40,000 breast cancer–related deaths among women are expected in 2014) (8). Risk factors for breast cancer in men are listed in Table 10.2.

Clinically, some reports suggest that male patients present at an older age (median age of 67) than female patients with a painless, hard mass most commonly in the subareolar area or, second in frequency, the upper outer quadrant of the breast; they can, however, occur anywhere in the breast. Skin or nipple retraction may be present and, some patients, present with spontaneous nipple discharge. Axillary adenopathy is identified in approximately 50% of patients at the time of presentation. As with breast cancer in women, prognosis depends on the status of the axillary lymph nodes and the size of the tumor at the time of diagnosis. Unfortunately, many men delay seeking medical attention for breast cancer–related signs and symptoms.

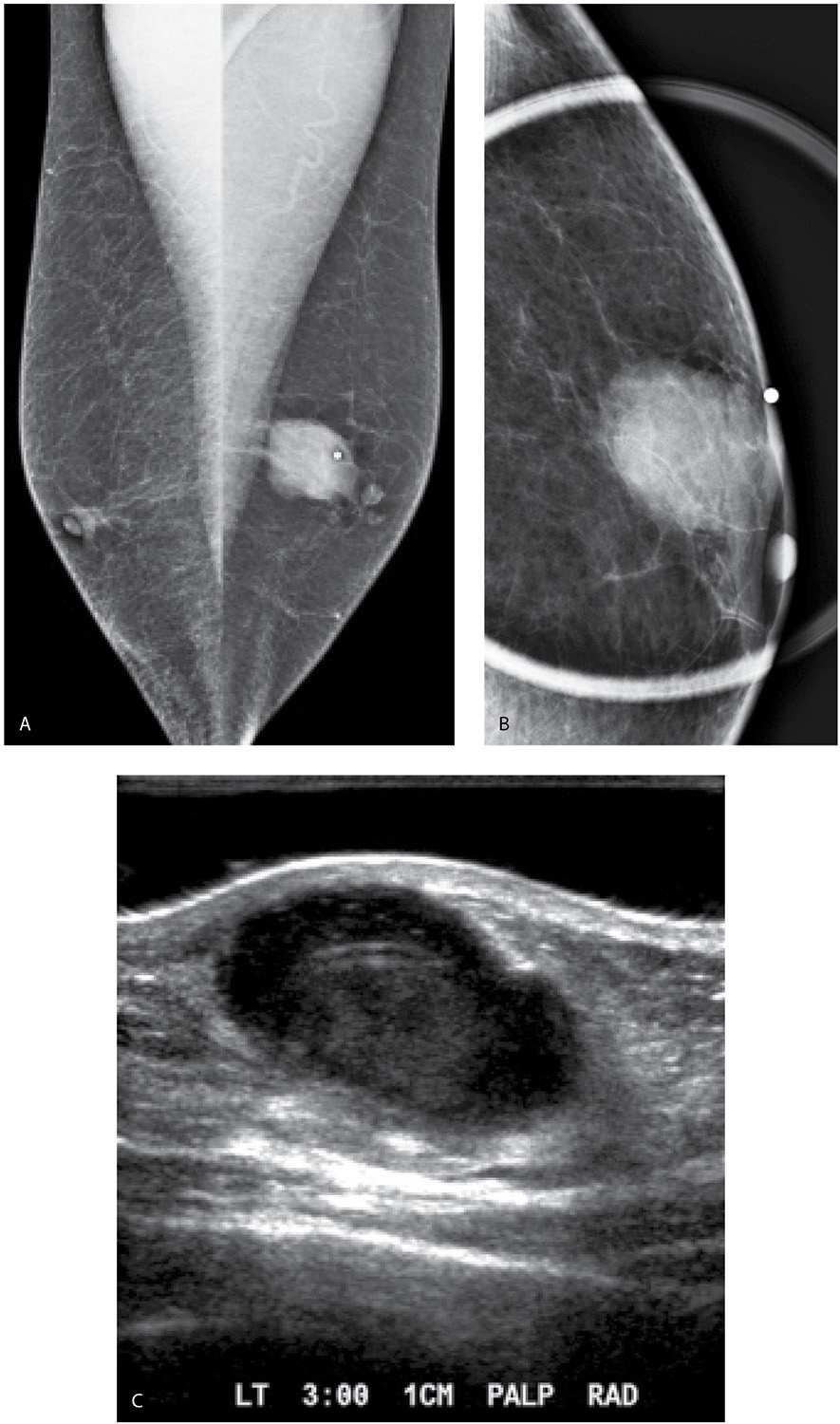

FIG. 10.8 • Fat necrosis. A: Left craniocaudal view. Two adjacent iso- to low-density masses with indistinct margins are imaged corresponding to a “lump” described by a 74-year-old man. Metallic BB used to denote palpable finding. B: Ultrasound. Two adjacent hyperechoic masses (arrows) with central hypoechoic areas are imaged corresponding to the palpable finding. The ultrasound features of these lesions are consistent with fat necrosis. Follow-up ultrasound 6 weeks later (not shown) demonstrates near complete resolution of the findings. C: Left mediolateral oblique view in a different patient presenting with a “lump.” Architectural distortion is imaged at site of clinical concern (arrow). D: Ill-defined area of hyperechogenicity (thick long arrows) with heterogeneity as well as an area of hypoechogenicity (thick short arrow) and some shadowing corresponding to the site of the palpable finding. The ultrasound features are consistent with fat necrosis. Associated skin thickening is noted (thin arrows). The patient has a history of trauma to this site with complete resolution of the imaging findings on follow-up studies (not shown). (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

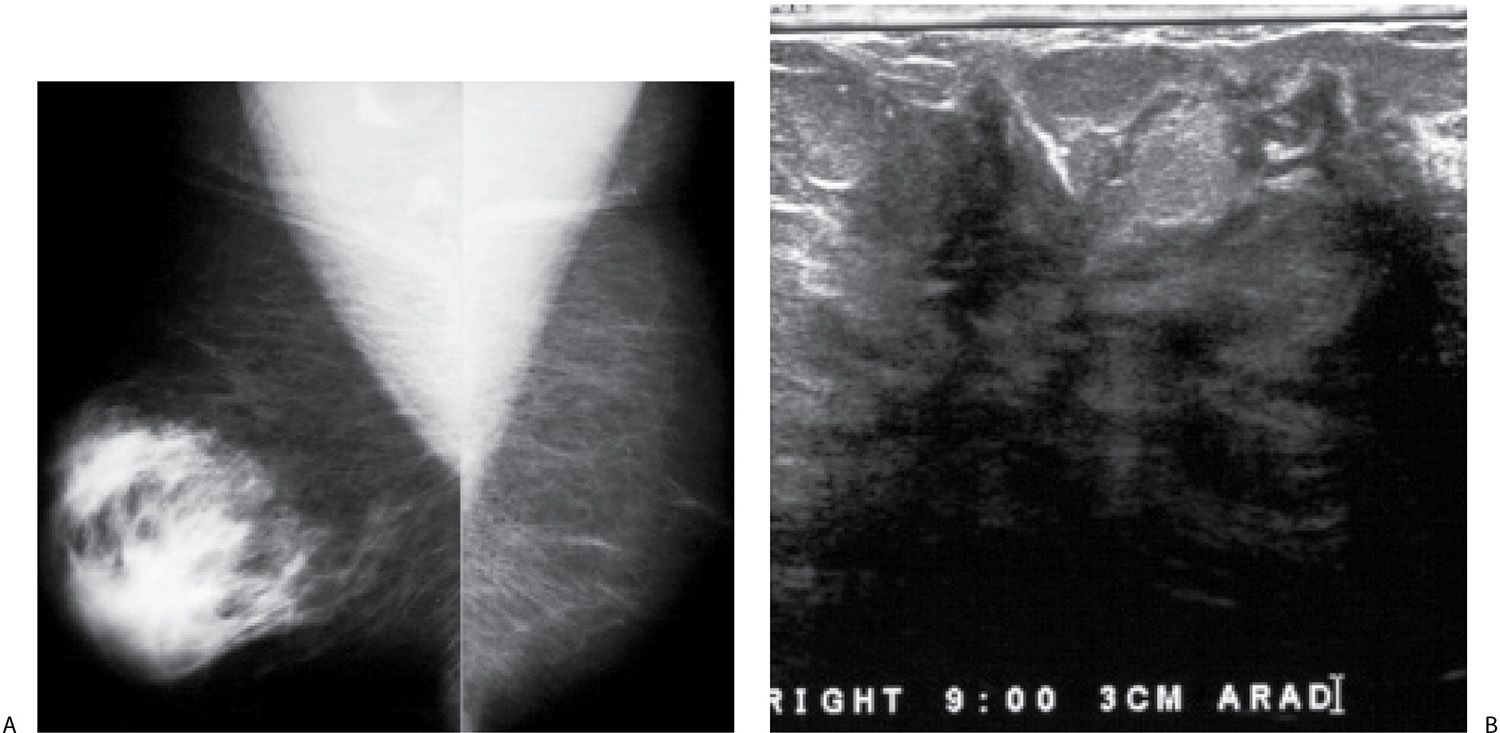

FIG. 10.9 • Abscess. A: Mediolateral oblique views in a 64-year-old man presenting with a “lump” in the left breast. Metallic BB used to denote site of “lump.” Note small nipples typical of male patients. B: Spot tangential view demonstrates a round isodense mass with indistinct margins as well as focal skin thickening. Metallic BB denotes the palpable finding. C: Ultrasound. On physical examination, a 3 cm round area of erythema is noted at the left periareolar margin at the 3 o’clock position. No significant tenderness is elicited at this site. A complex cystic and solid mass with posterior acoustic enhancement is imaged abutting the skin correlating to the clinical and mammographic findings. An aspiration with possible core biopsy to follow is discussed with the patient. Approximately, 2 mL of thick purulent fluid is aspirated.

FIG. 10.10 • Unilateral dense gynecomastia and pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH). A: Mediolateral oblique views in a 53-year-old man who presents describing rapid enlargement of the right breast with a more focal site of nodularity laterally. The right breast is larger than the left and further characterized by the presence of dense glandular tissue. Fatty tissue is imaged in the left breast. B: Ultrasound. Irregular masses with disruption of normal tissue planes and shadowing are imaged at the site of nodularity described by the patient laterally in the right breast. With rotation of the transducer, these areas become less prominent. Gynecomastia and PASH are diagnosed on an ultrasound guided core biopsy through this tissue. Although PASH typically presents with a mass, rapid breast enlargement has been described as an unusual presentation (see Chapter 7) for PASH.

Table 10.2 RISK FACTORS FOR MALE BREAST CANCER

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree