A sheepish older guy with a breast lump is in your department. Without even seeing him, you know that the most likely diagnosis is gynecomastia. But let’s make sure that it’s not more serious. At diagnosis, breast cancer in men tends to be more advanced than in women and will nearly always be invasive. The distinction between gynecomastia and cancer is important—a delay in diagnosis may change the stage of the disease.

Men are pretty easy in the world of breast imaging. Lesions other than gynecomastia and invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) are really uncommon. Fortunately, male breast cancer is much less common than gynecomastia and distinguishing between the two is usually very straightforward. Sometimes gynecomastia is mass-like in appearance, and the features on ultrasonography (US) can be suspicious. In this chapter, we’ll focus on how to tell gynecomastia and cancer apart and review a few uncommon male breast lesions that you might see in your practice.

Male Breast Tissue Composition

Until puberty, male and female breasts are the same. During puberty, female breasts experience ductal elongation and branching followed by lobular proliferation, but male breasts do not. Normal male breasts therefore only have atrectic ducts and few lobules. The normal male breast consists primarily of fat with a small amount of ductal tissue in the subareolar regions. Intramammary and axillary lymph nodes are commonly seen ( Fig. 16-1 ). Lesions of lobular origin, such as fibroadenomas, cysts, and lobular carcinoma, are uncommon.

Gynecomastia

Gynecomastia is non-neoplastic enlargement of the male breast due to hyperplasia of epithelial and stromal elements. Gynecomastia develops as a result of an imbalance between estrogen and androgen actions within the breast tissue. Physiologic gynecomastia presents at times when there is a normal change in the balance between these hormones. It occurs in over half of adolescent boys and usually regresses within 6 months of diagnosis. Gynecomastia is also present in about half of older men—usually over 65—in whom it is often asymptomatic.

Between these age peaks, gynecomastia is usually pathologic. It may be caused by one of a variety of different diseases, syndromes, medications, or other substances that increase estrogen or decrease testosterone ( Box 16-1 ). The clinical history can give clues to the cause. Is he an awkward teenager? A bartender with a red nose? An older guy being treated for prostate cancer? Gynecomastia is often idiopathic, so the cause is not always apparent. Confirming a diagnosis of gynecomastia is important because it often allows the patient to be successfully treated if the cause is identified, and provides reassurance to the patient that the findings are not malignant.

- •

Physiologic

- •

Idiopathic

- •

Increased body mass index

- •

Medications

- •

Chemotherapeutic agents

- •

Cimetidine

- •

Diazepam

- •

Digitoxin

- •

Estrogen

- •

Metoclopramide

- •

Phenytoin

- •

Prostate cancer therapy (antiandrogens, estrogen)

- •

Spironolactone

- •

Steroid hormones

- •

Thiazides

- •

Tricyclic antidepressants

- •

- •

Drug use

- •

Anabolic steroids

- •

Alcohol

- •

Marijuana

- •

Opioids

- •

- •

Hyperthyroidism

- •

Cirrhosis

- •

Chronic renal failure

- •

Neoplasms

- •

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- •

Adrenal carcinoma

- •

Testicular tumors

- •

- •

Klinefelter syndrome

Breast enlargement can also be caused by pseudogynecomastia , which is an increase in adipose tissue rather than enlargement of the fibroglandular tissue. Gynecomastia can usually be differentiated from pseudogynecomastia on clinical examination. In gynecomastia, a mound of tissue concentric to the nipple is generally appreciated. However, this finding is absent in pseudogynecomastia. Because there is no suspicious palpable mass and the enlargement is due to fat, the diagnosis is usually apparent on clinical examination and mammography ( Fig. 16-2 ).

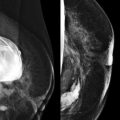

Mammographic Patterns of Gynecomastia

There are three patterns of gynecomastia based on the mammographic appearance: nodular, dendritic, and diffuse fibroglandular. In one series, among 61 cases of biopsy-proven gynecomastia, 47 (77%) were nodular, 12 (20%) dendritic, and 2 (3%) were diffuse fibroglandular. An awareness of these patterns aids in the recognition of gynecomastia, and helps differentiate it from potentially malignant findings.

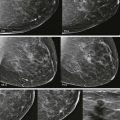

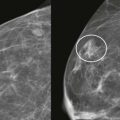

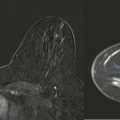

With the nodular type, there is typically a flame-shaped density (also described as triangular or fan-shaped), centered behind the nipple, that radiates posteriorly and blends into fat ( Figs. 16-3 and 16-4 ). This type occurs during the acute florid phase and usually lasts for less than 1 year. The breast is often tender. If US is performed, prominent hypoechoic ducts and edematous adjacent tissues are often visualized, and increased blood flow is common on Doppler examination ( Fig. 16-5 ). The main histologic findings in this phase are ductal proliferation with loose, cellular stroma and edema.

If gynecomastia persists, the findings may progress to the dendritic pattern. This is a chronic, fibrotic phase that can develop when gynecomastia has been present for at least 1 year. The term “dendritic” originates from the Greek language and refers to a tree branching. Mammography shows retroareolar breast tissue that radiates posteriorly in a fairly typical pattern, resembling tree branches ( Figs. 16-6 and 16-7 ). At this stage, symptoms have usually abated and the gynecomastia is unlikely to regress either spontaneously or with treatment. If US is performed, the appearance will be similar to female breast tissue with mostly hyperechoic fibrous tissue and small ducts. Edema and increased blood flow have resolved. The histologic findings at this stage are dominated by periductal fibrosis and hyalinization of the stroma.

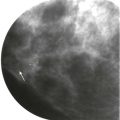

Diffuse fibroglandular gynecomastia is another pattern that occurs in men receiving estrogen treatment. The breasts are enlarged with a diffuse increase in density, producing an appearance similar to that of a mammogram of a female patient with dense tissue ( Fig. 16-8 ). With this pattern, both nodular and dendritic features may be present.

Male Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is uncommon in men, accounting for about 0.5% of all breast cancers and less than 1% of all malignancies diagnosed in men. Incidence increases with age and plateaus at about 80 years of age; the median age of diagnosis is 67 years. Breast cancer is very uncommon in younger men.

Family cancer history is important for men and women. About 25% of men diagnosed with breast cancer are BRCA gene carriers, more commonly BRCA2 . Men with a BRCA2 mutation have a 7% risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer by age 70 years. Diagnosis of breast cancer in a man is much more likely to be associated with a BRCA mutation than diagnosis of breast cancer in a woman, and a man’s family is therefore at higher risk for a genetic mutation as well. Men with breast cancer and women with a first-degree male relative with breast cancer are typically referred for genetic counseling.

Risk factors for male breast cancer other than family history include Klinefelter syndrome, androgen deficiency (undescended testes, orchitis, testicular trauma or torsion), cirrhosis, and chronic alcoholism. Some of the risk factors for male breast cancer involve chronic elevation of the ratio of estrogen to androgen, which is interestingly the same hormonal imbalance that underlies the development of gynecomastia. Although it has been difficult to establish gynecomastia as a risk factor for breast cancer, the two often occur together; this is not surprising given the overlapping risk factors and high prevalence of gynecomastia. In one study, 22 out of 55 (40%) male breast cancers occurred in patients with gynecomastia.

Most male breast cancers arise from ducts in the subareolar region, and the most common clinical presentation is a palpable mass that is eccentric but near the nipple. Palpable axillary adenopathy is common at the time of presentation. However, axillary adenopathy is rarely the sole presenting finding. Nipple discharge is an uncommon presentation.

The large majority of male breast cancers are infiltrating ductal carcinomas, not otherwise specified. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) may also occur, usually in association with IDC. Pure DCIS is uncommon. Other subtypes of ductal carcinoma are much less common; however, all subtypes that occur in women have also been reported in men. Infiltrating lobular carcinoma is rare. In a large series, 93.7% of male breast tumors were either ductal or unclassified carcinomas, 2.6% were papillary carcinomas, and only 1.5% were lobular carcinomas ( Box 16-2 ).

- •

In the United States, the screening threshold is set as the risk of breast cancer equal to or greater than that of a 40-year-old woman, which is 120/100,000 per year. To screen any other population with mammography, the risk should be equal to or greater than this risk level.

- •

Overall, the risk of breast cancer for men is 1.2/100,000, which is well below the threshold for screening in the United States.

- •

Men who are known or suspected BRCA carriers may benefit from screening mammography. These men are at substantially increased risk compared with the general male population. Their risk approaches that of women in their 40s.

- •

Of male patients with gynecomastia, only those with Klinefelter syndrome approach the screening range. Screening of these men remains controversial. Men with gynecomastia due to gender reassignment with hormone therapy are not at high risk for breast cancer. Routine screening mammography is not indicated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree