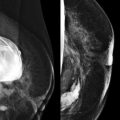

Four o’clock and you are winding down the day. The mammography technologist brings you a mammogram of a 41-year-old woman with a breast lump. It looks negative. You ask the ultrasound technologist to scan the area, or how about scanning both breasts just to be safe. She returns a bit later with 24 images from each radian of both breasts. Looks okay.

Are you done? Wait. Don’t let her leave. Go talk with her. Examine the lump and put the ultrasound transducer directly over it and really look. It will only take a few minutes and could save her life and your neck! Yes, your technologists can be trained to do this well too, though it takes dedication and feedback from the radiologist.

Radiologists have few opportunities to actually see patients, with the exception of breast imaging and interventional radiology. A busy breast-imaging practice may seem more like a clinic than a typical reading room. The radiologist covering diagnostics may spend more time out of the reading room talking with and examining patients than reading mammograms. Interacting with patients can seem intimidating at first, but hey, we all went to medical school. Obtaining a history and doing a focused clinical breast examination are extremely helpful in directing you to a significant finding.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Breast pain (mastalgia) is a common complaint. About 60% of women will seek medical attention at some point in their life for evaluation of breast pain. Fortunately, pain is rarely the sole presenting complaint for breast cancer. On the other hand, a palpable breast finding that is painful can definitely be cancer.

Breast pain can be classified as cyclic or noncyclic. Breast pain that is worst just before the menstrual cycle (luteal phase) is due to swelling resulting from elevated progesterone levels. Reassurance is all that is needed in most cases. For severe mastalgia, treatment with androgens or antiestrogens may be recommended.

However, very commonly when you ask a woman to point to the area of tenderness, she points to a costochondral junction or rib. In fact, noncyclic breast pain is often not due to pain in the breasts at all, but to costochondritis. Most women are just really worried that they have breast cancer; they are usually very happy to find out that their symptoms are not even related to their breasts.

In a study of 916 women presenting to a breast clinic with the primary symptom of breast pain, six women were diagnosed with breast cancer. All of these women either had a palpable lump in the symptomatic region or cancers unrelated to the symptomatic region that were detected mammographically. In addition, this study found that rather than providing reassurance to these women, immediate imaging evaluation for breast pain increased subsequent unnecessary utilization of medical services.

Bilateral or cyclic breast pain does not require diagnostic evaluation. For women with focal noncyclic breast pain and a normal clinical examination, diagnostic evaluation may be performed but is not mandatory. If a patient with mastalgia has negative mammography and the breasts are fatty replaced, it is unlikely that ultrasonography (US) will add useful information. Additional imaging may serve to reassure the patient, but our experience and the preceding study show that the likelihood of finding a cancer is exceedingly low.

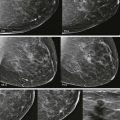

If the patient with mastalgia has an abnormal clinical examination, diagnostic evaluation should be performed and management based on evaluation of the palpable abnormality. For women age 40 or older, a mammogram is a good place to start. US is usually performed as well, and when a dominant cyst is found, aspiration may provide some relief ( Fig. 14-1 ). Cysts that are more round and distended are more likely to cause tenderness than those that are more flaccid.

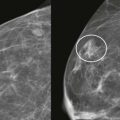

Skin dimpling, focal skin thickening, or nipple retraction . Retraction or dimpling of either the skin or nipple may be due to an underlying invasive carcinoma. Focal skin thickening may be due to invasion of the dermis by carcinoma. Spot compression or tangential views and US of the underlying area will identify most malignancies causing these findings ( Fig. 14-2 ). If the clinical finding is suspicious and the imaging is negative, patients in our practices are often referred for surgical evaluation. When the clinical findings are of high suspicion, an MRI may also be performed and may reveal a malignancy that is not apparent on either mammography or US.

Paget disease (nipple eczema) presents as excoriation of the skin of the nipple ( Fig. 14-3 ) and is often diagnosed by a dermatologist. Most women with this presentation have cancer cells—most commonly high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)—involving the cutaneous tissues of the nipple. An invasive ductal component is often present and may be distant from the nipple. The diagnosis can be made by punch biopsy of the nipple skin by a surgeon or dermatologist. The punch biopsy will show cancer cells percolating up to the dermis. If an invasive cancer is identified, there will virtually always be DCIS extending between the invasive carcinoma and the nipple. Paget disease is rarely associated with invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC).

Excoriation of the nipple can also occur with discharge due to an intraductal papilloma, though this is a much less common cause. In these cases, the nipple punch biopsy will be negative.

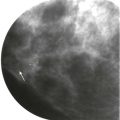

Breast edema is often due to benign causes such as fluid overload, congestive heart failure, or renal failure. This usually results in bilateral symmetric edema, though it is sometimes asymmetric due to sleeping habits or prior surgery or radiation. Unilateral breast edema is more concerning, but is also frequently benign as long as there is no erythema. On mammography, edema produces skin and trabecular thickening ( Fig. 14-4 ). The findings are usually diffuse and may be more pronounced in the dependent portions of the breasts.

Breast inflammation presents as a warm red breast and is concerning for either mastitis or inflammatory breast cancer ( Fig. 14-5 ). Mammography will show breast edema. If a suspicious mass is identified on imaging, biopsy should be performed. If mastitis is suspected, the patient can be given a trial of antibiotics for 10 to 14 days. With mastitis, the symptoms should resolve. Women with inflammatory breast cancer often have mild associated cellulitis and can show some improvement in symptoms with antibiotic treatment. If the inflammatory signs and symptoms do not clear completely, a dermal punch biopsy is necessary to exclude inflammatory breast cancer. The punch biopsy will show invasion of dermal lymphatics by tumor cells.

Focal pain associated with warmth and redness may indicate an underlying abscess. Breast abscesses are more common in women who smoke, and unfortunately, tend to be recurrent and difficult to treat with antibiotics alone. Mammography may show focal skin thickening but is usually not specific and often painful. US can be helpful in identifying the presence, location, and size of an abscess ( Fig. 14-6 ). In some cases, smaller abscesses can be successfully treated by ultrasound-guided aspiration and antibiotic therapy. Surgical drainage is often necessary, especially for larger collections. Abscesses can also be relatively cold in the breast, presenting with minimal or no symptoms, and can even mimic breast cancer.

Palpable breast lumps are common. Most palpable lumps are discovered by the patient, and most are benign ( Box 14-1 ). Those in postmenopausal women have a higher chance of malignancy. Malignant palpable lumps often produce nonspecific clinical findings that cannot be distinguished from benign lesions ( Fig. 14-7 ). In one study, about 6% of women ages 40 to 69 in a large HMO (health maintenance organization) presented for evaluation of a breast lump over a 10-year period. Of those women, about 10% were subsequently diagnosed with breast cancer.

- •

Normal tissue

- •

Ridge of tissue

- •

Lactiferous sinus

- •

Lymph node

- •

Montgomery gland cyst

- •

- •

Skin lesions (sebaceous cyst, epidermal inclusion cyst)

- •

Benign lesions

- •

Cyst or fibrocystic change

- •

Lipoma

- •

Oil cyst

- •

Hamartoma

- •

Galactocele

- •

Fibroadenoma

- •

Papilloma

- •

Scar

- •

- •

Cancer (IDC > ILC > DCIS)

Palpable breast thickening is defined as firmness of the breast tissue that is less discrete than a palpable lump. We evaluate palpable thickening in the same manner as palpable lumps, with routine and spot compression mammographic views and US. Comparing the potentially abnormal area with the palpable texture of the rest of that breast or the opposite breast on clinical examination is very helpful in gauging the level of suspicion. Thickening is often normal, although about 5% of women with this symptom may have breast cancer. ILC and DCIS may present with palpable thickening ( Fig. 14-8 ).

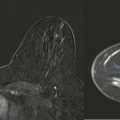

Neglected breast cancer manifests clinically as a shrunken very hard breast, often with associated erythema ( Fig. 14-9 ). This is sometimes referred to as a “mummified” breast. Palpable ipsilateral axillary adenopathy is common. Skin nodules or erosion due to dermal metastasis may also be present. Mammography is quite difficult and may not be helpful in management. Imaging for evaluation of regional and distant disease may be helpful in staging and management. The most frequent histologic finding associated with this presentation is invasive ductal carcinoma–not otherwise specified (IDC-NOS). This appearance should not be confused with the mammographic finding of the “shrinking breast” of ILC, which is associated with minimal clinical symptoms.

Evaluation of the Symptomatic Patient

Clinical history is helpful in assessing the relative importance of the clinical finding ( Box 14-2 ). The easiest way to start is to simply ask the patient, “Can you tell me about the lump?” as you are washing your hands. (P.S. Always do this in front of the patient. Love, Mom and Dad) This will usually provide you with all of the information that you need. In our experience, a history of, “Well, it was here last week, but now it has moved over to this spot. It moves around a lot,” has a negative predictive value of nearly 100%.

- •

Who found the lump and when?

- •

If your doctor found it, has this doctor examined you before?

- •

Do you perform breast self-examination on a regular basis?

- •

Has the finding changed? Have you had a menstrual cycle since it was found?

- •

Are there multiple lumps or one dominant lump?

- •

Have you had surgery to that region?

- •

Have you had recent trauma to that region?

- •

Have you had any signs or symptoms of infection?

Clinical breast examination is usually performed in conjunction with US and can be limited to the area of concern ( Fig. 14-10 ). If the patient can only find the palpable abnormality when in a certain position (e.g., sitting up), the examination should take place in that position. If the area is firm and different in texture compared with the rest of the breast, the level of suspicion should be high.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree