Age (years)

Normal

Acute pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis

1–3

1.13

1.9

n.a.

4–6

1.35

2.07

n.a.

7–9

1.67

2.13

2.42

10–12

1.78

2.34

2.77

13–15

1.92

2.56

2.91

16–18

2.05

2.63

3.15

Examination of the pancreas should always be considered as an integral part of a comprehensive evaluation of the hepatobiliary system, in addition to the mandatory examination of the bile duct, gallbladder, and liver parenchyma.

Age-Dependent Size and Echogenicity

The size of the pancreas is age dependent, with a high interindividual variability [2, 3]. Measurements of the pancreas, particularly during routine scans in otherwise healthy children without pancreatic disorders, are optional and usually have no clinical significance. The corpus of the pancreas is usually the easiest part to assess. When taking measurements, the anterior–posterior diameters of all parts of the pancreas should be obtained and reported (see age-depending dimensions in Table 7.2). The most substantial growth of the pancreas occurs in the first year of life [2, 3]. Pathologic increase in size at a young age mostly occurs in cases of acute pancreatitis or congenital hyperinsulinism (formerly known as nesidioblastosis). Patients with chronic pancreatitis often have normal or decreased pancreatic caliber due to fibrosis [1]. In cases of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), studies have shown that long duration of the disease was associated with a reduction in the size of the pancreas at all ages. Furthermore, the decrease in the size was correlated with the severity of insulin deficiency due to fibrosis [4].

Table 7.2

Average approximate age-dependent sonographic measurements of the pancreas in centimeters. (Adapted from [1])

Age (years) | Normal | Acute pancreatitis | Chronic pancreatitis |

|---|---|---|---|

1–3 | 0.98 | 1.15 | n.a. |

4–6 | 1.01 | 1.22 | n.a. |

7–9 | 1.04 | 1.30 | 1.05 |

10–12 | 1.06 | 1.35 | 1.15 |

13–15 | 1.11 | 1.37 | 1.15 |

16–18 | 1.18 | 1.43 | 1.20 |

In healthy children, the echo structure of the pancreas appears “cobblestone-like” on high-resolution ultrasound imaging. In infants, the echogenicity initially appears similar to liver , becoming more hyperechogenic with increasing age (Fig. 7.1a, b). In newborns, however, the pancreas may also be transiently slightly hyperechoic [5]. Reasons for diffuse hyperechoicity include fibrosis, fatty degeneration, long-term corticosteroid or cytostatic therapy, Shwachman–Diamond syndrome, congenital hyperinsulinism, chronic pancreatitis, edematous pancreatitis, hemosiderosis, parenteral nutrition, Cushing’s disease, and obesity. Focal alterations of the size and echogenicity are described separately below.

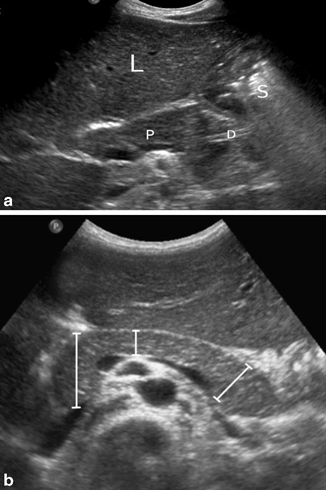

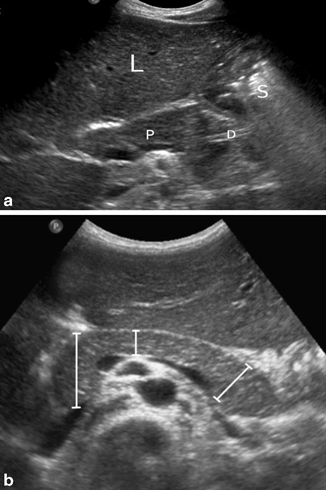

Fig. 7.1

a Normal pancreas (P) imaged through the left lobe of the liver (L). The pancreatic duct is partially visible (D), while the tail is obscured by the gas-containing stomach (S). b Transverse ultrasonography (US) image shows the measurements of the head, body, and tail of the pancreas in a child. [6]

Sonographic Pathology of the Pancreas

Pancreatic Embryology and Related Anomalies

The embryological fusion of the pancreas from a ventral and dorsal bud gives rise to a certain variance in the anatomy of the major and minor pancreatic duct. Note that in 60 %, the two ducts insert separately into the duodenum, whereas in about 30 %, the individual ducts unite before the main pancreatic duct drains into the duodenum in a single location. Pancreatic duct anomalies can predispose to recurrent pancreatitis.

Pancreas divisum is the most common anatomical variant and occurs if no or only incomplete fusion of the ventral and dorsal bud takes place. The major portion of the pancreatic secretion drains into the duodenum through the minor papilla via the dorsal duct. It can be a reason for recurrent pancreatitis due to relative obstruction, but the need of therapy in asymptomatic cases is still controversial. Ultrasound is the first diagnostic tool to rule out pancreatitis or pancreatic pseudocysts as a manifestation of pancreas divisum. In order to clearly evaluate the ductal anomaly, ultrasound should be complemented by endoscopic retrograde cholecystopancreatography (ERCP) or magnetic resonance cholecystopancreatography (MRCP). However, new ultrasound techniques , including secretin-stimulated ultrasonography (US) [7] or endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) [8], have also been employed and may be more accurate.

Annular pancreas can cause congenital duodenal obstruction, seen on ultrasound as the typical “double bubble” appearance as an indirect sign of the diagnosis.

Acute Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis in children is rare, but recent studies found that the prevalence is increasing, possibly due to improved diagnostic tools or higher awareness [9]. It is associated with a high mortality and morbidity [10]. While idiopathic in 23 % of cases, the most common causes are trauma (22 %), structural anomalies (15 %), multisystem disease (14 %), drugs and toxins (12 %), as well as viral infections (10 %). Cholelithiasis causing pancreatitis due to obstruction has previously been considered unusual [11], but lately the incidence has been increasing, in part due to a rise in pediatric and adolescent obesity (Fig. 7.2) [12].

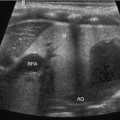

Fig. 7.2

Gallstone pancreatitis. The pancreatic head (PH) is echogenic and swollen. The pancreatic duct (1) is mildly dilated. The mesenteric artery is visible (A) as a landmark

Acute pancreatitis is defined by an acute onset of symptoms (abdominal pain, vomiting, paralytic ileus, rebound tenderness, jaundice), elevated levels of serum/urine amylase, and a pathological ultrasound with compromise of pancreatic structure and function. Factors secondary to the pancreatitis itself may obscure the sonographic diagnosis, particularly in children. For example, increased intestinal gas due to paralytic ileus or lack of compliance due to pain can negatively impact the examination.

Ultrasound may show an increase in anterior–posterior diameter of the pancreas, usually because of edematous swelling with diffuse or focal-elevated echogenicity. Organ enlargement, however, can be absent in up to 50 % of cases. Peripancreatic fluid is another typical finding (Fig. 7.3). As mentioned beforehand, dilation of the pancreatic duct greater than 1.5 mm in children between 1 and 6 years, 1.9 mm at ages 7–12 years, 2.2 mm at ages 13–18 years is significantly associated with the presence of acute pancreatitis [1].

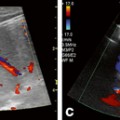

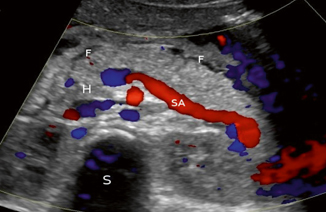

Fig. 7.3

Doppler study of acute pancreatitis. The head (H) and body of the pancreas are visible, with the splenic artery (SA) serving as a landmark. The spine is in the background (S). There is peripancreatic fluid (F) visible as a sign of inflammation

In summary, diagnostic accuracy of acute pancreatitis by native ultrasound depends on severity, the presence of complications such as paralytic ileus, typical associated findings, including a pancreatic pseudocysts, as well as operator experience. Increased diagnostic accuracy can be achieved with contrast-enhanced ultrasound, which is particularly useful to detect ischemic areas seen with pancreatic necrosis [13]. Using ultrasound elastography to gain information about organ stiffness not accessible to exterior palpation could also increase the rate of correct diagnosis in the future, but is currently mostly experimental [14].

When in doubt, the diagnostic tools can be extended to MRCP with full imaging of the pancreatic duct system, discovering structural anomalies. In most young children, sedation or full anesthesia is needed for this study, and visualization of ducts with a diameter less than 1 mm is still difficult [15].

Chronic Pancreatitis

In chronic pancreatitis—which is rather rare in children—the etiology includes cystic fibrosis, fibrosing pancreatitis, hereditary chronic pancreatitis, inborn errors of metabolism, or structural anomalies (Fig. 7.4). Chronic pancreatitis is defined as a combination of clinical symptoms such as abdominal pain, exocrine (malabsorprion, steatorrhea, etc.) and endocrine dysfunction (diabetes mellitus), along with imaging findings characteristic of the irreversible morphologic damage of the pancreatic parenchyma [10, 16–18].

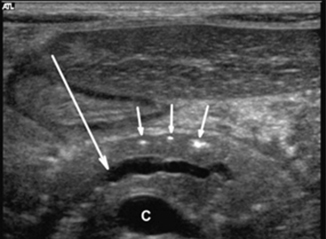

Fig. 7.4

Transverse ultrasonography (US) image in a 5-year-old boy with chronic hereditary pancreatitis shows the typical features of chronic pancreatitis: calcifications (small arrows) and dilatation of the pancreatic duct (large arrow). C confluence of the superior mesenteric and splenic veins [19]

The sonographic examination of chronic pancreatitis may show inhomogeneous echogenicity and prominent margins caused by progressive fibrosis and fatty injections of the gland. The size of the pancreas can be normal or reduced. The duct appears dilated and sometimes irregular in its course, with intermittent dilation and stenosis. Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy to confirm the diagnosis has been found to have a lower complication rate (1 %) than ERCP [15]. Potential complications of chronic pancreatitis are pseudocyst formation, focal calcifications, and recurrent intraductal stones (Fig. 7.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree