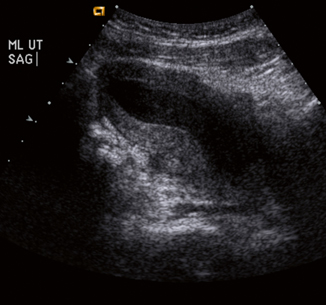

Fig. 15.1

a Ultrasound of a newborn demonstrates a more prominent fundus of the uterus in comparison to the cervix. The endometrium is also more prominent and visible. b Ultrasound of a 6-month-old shows a uterine fundus smaller than the cervix. c Ultrasound of an 8-year-old demonstrates a tubular appearance of the uterus with the fundus and cervix similar in size. d Ultrasound in a 15-year-old shows a typical postpubertal appearance of the uterus with a prominent fundus in relationship to the cervix as well as a prominent endometrium

Clinical Problems

Ambiguous Genitalia

Ambiguous genitalia requires a complicated diagnostic evaluation. However, the role of sonography is straightforward to prove or disprove the presence of the uterus and to describe the degree of hypoplasia or agenesis, if applicable. Müllerian duct abnormalities affect the proximal two thirds of the vagina, cervix, and uterus [6]. The distal third of the vagina develops from the urogenital sinus [7]. US should also look for and describe the gonadal structures, if visible. Evaluation of the adrenal glands and kidneys is also necessary, as abnormalities of those organs can be linked.

Uterine Malformations

Uterine malformations result from the disruption of the fusion of the Müllerian ducts during development [6]. Currently, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred means of evaluation. Ultrasonography, however, can provide a rapid, inexpensive, and relatively risk-free assessment. The US can evaluate the uterine contour, the shape of the endometrial cavity, and if there is duplication of the cervix and/or vagina. An arcuate uterus is demonstrated by a mild indentation of the endometrium at the fundus with a normal fundal contour [6]. If the endometrial cavity is further divided while maintaining the fundal contour, the uterus is considered septated [6]. Both didelphys and bicornuate uterus are characterized with a duplicated endometrial cavity as well as a fundal cleft [6]. Uterus didelphys also duplicates the cervix and proximal vaginas (Fig. 15.2a and b) [6]. In bicornuate uterus, the cervix may be duplicated (bicornuate bicollis) or without duplication (bicornuate unicollis) [6]. A unicornuate uterus is more easily characterized due to the presence of a single uterine horn with agenesis or hypoplasia of the contralateral horn [6].

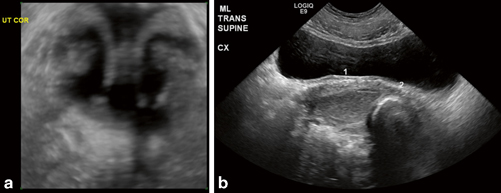

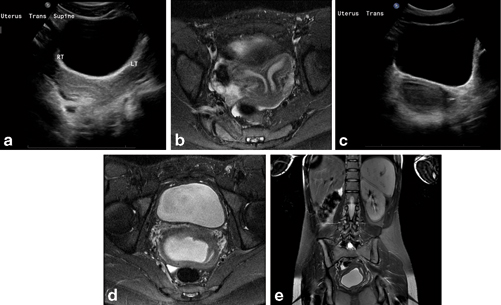

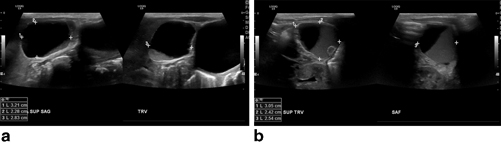

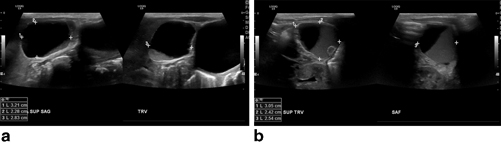

Fig. 15.2

a 3-D ultrasound demonstrates a uterus with two separate endometrial cavities and two cervixes. b A didelphys uterus is confirmed with the presence of duplication of the vagina. The first vagina is distended with complex fluid consistent with blood products. A tampon demonstrating acoustic shadowing is present in the second vagina

Pelvic Mass

Sonography is the initial examination of choice for evaluating a patient with a suspected pelvic mass. Primary tumors of the uterus and vagina are unusual in the pediatric population and are commonly malignant [3]. Rhabdomyosarcoma can arise from the uterus or vagina and has a nonspecific US appearance; the diagnosis is usually suggested by the location rather than a specific appearance. It typically exhibits as a well-circumscribed hypoechoic inhomogeneous mass and also has vascularity on color Doppler imaging [1]. Clear cell adenocarcinoma can arise from the vagina in children younger than 2 years of age who have a history of exposure to diethylstilbestrol in utero [2]. It has a similar appearance to rhabdomyosarcoma [2].

More commonly, genital tract obstruction presents as a pelvic mass in the pediatric population. The vagina (hydrocolpos) or the vagina and uterus (hydrometrocolpos) can become distended with fluid and appear as a tubular cystic midline mass (Fig. 15.3) [2, 3, 5]. The uterus can be identified because of the thickness of its wall [3]. The obstruction is typically due to an imperforate hymen, but can also be secondary to cloacal or urogenital sinus malformations [2, 3, 5]. If the uterus is obstructed alone (hydrometra), this is usually due to cervical agenesis or obstruction of one horn of a bicornuate uterus [3]. If distended with blood, then the term is hematocolpos, hematometrocolpos, or hematometra.

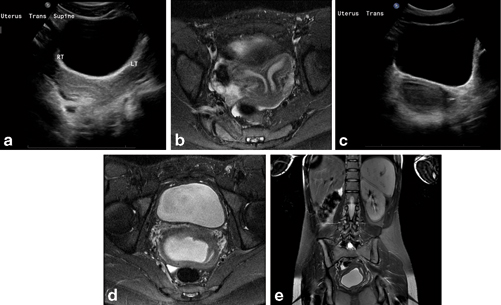

Fig. 15.3

Ultrasound shows a distended uterus and vagina with complex fluid representing blood products consistent with hematometrocolpos

Syndromes

Pelvic anomalies are not always isolated findings. Congenital malformations may involve a part or all of the Müllerian or Wolffian duct, which can lead to associated anomalies. In Mayer–Rokitansky–Küster syndrome there is complete agenesis of the uterus and the upper two thirds of the vagina. Patients can have associated malformations including unilateral renal aplasia, ectopic locations of the kidney, horseshoe kidney, double ureter, and vertebral malformations [7].

Herlyn–Werner–Wunderlich syndrome is another constellation of anomalies affecting the Müllerian and Wolffian duct. The syndrome is characterized by uterine didelphys (Fig. 15.4a and b), obstructed hemivagina (Fig. 15.4b and c), and ipsilateral renal agenesis (Fig. 15.4e) [8].

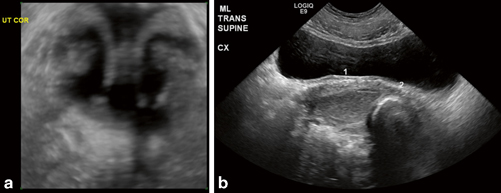

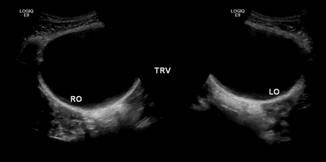

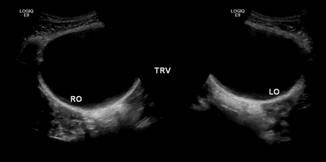

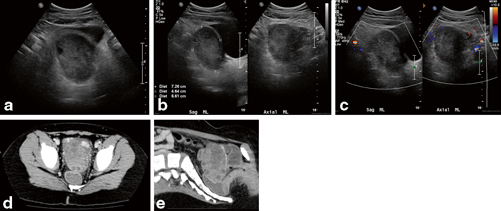

Fig. 15.4

a Transverse ultrasound view of the pelvis demonstrates a uterus with duplicated uterine bodies. b MRI coronal STIR sequence shows duplication of the uterine body and cervix consistent with uterine didelphys. c Traverse ultrasound view shows duplication of the vagina with distension of the right hemivagina with echogenic fluid consistent with right-sided hematocolpos. d MRI axial STIR sequence shows a duplicated vagina with distension of the right hemivagina with blood products consistent with right-sided hematocolpos. e MRI coronal T2 with fat saturation shows right-sided renal agenesis. STIR short tau inversion recovery

Disorders of Puberty

With precocious puberty, pubertal delay, or amenorrhea, US is commonly used to evaluate the uterus and ovaries. The developmental morphology of the uterus can be identified with US and compared to the patient’s level of sexual development. Uterine and ovarian volume can be measured and compared to a reference of normal volumes at a given age. The number and size of ovarian follicles can also be assessed.

Others

Occasionally, targeted sonographic assessment is performed to evaluate the vaginal cuff. In the pediatric population, the common clinical indication is a site of inflammation and/or a palpable abnormality. With cellulitis of the labia, US can determine if there is an underlying fluid collection to suggest an abscess (Fig. 15.5). Vaginal cysts can also be identified, which can have superimposed infection. If US detects a cystic structure at the anterolateral wall of the vagina, above the inferior border of the pubic symphysis, this represents a Gartner duct cyst, which results from incomplete regression of the Wolffian ducts [9]. A cystic structure seen at or below the level of the pubic symphysis corresponds to a Bartholin gland cyst, which develops from obstruction of the gland’s duct [9]. If the cystic structure is identified in the periurethral area, then this represents a Skene gland cyst, which is also secondary to obstruction of the gland [9].

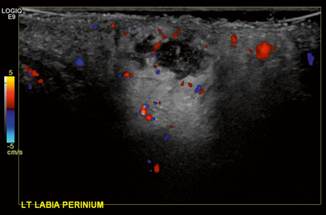

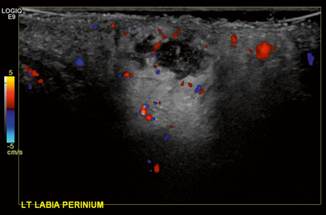

Fig. 15.5

Ultrasound of the left labia shows a complex fluid collection consistent with an abscess. There is also surrounding inflammatory changes and hyperemia

Female Pelvis—Ovaries

Normal Appearance

The size of the ovary is traditionally reported in length, width, and depth, with an approximate ovarian volume calculated by multiplying the product of these numbers by 0.523 [2]. Ovarian size varies with age, and neonatal ovarian volume correlates with birth weight and length [10]. Neonatal ovaries, like the uterus, are larger due to maternal estrogen stimulation and can contain multiple follicles. Ovarian volume can reach up to 3 cm3 during the first 3 months of life, decreasing in size over the first 2 years of life to a mean volume of approximately 0.67 cm3. Ovaries remain small until about 6 years of age, at which time they begin to grow again, continuing their enlargement through the prepubertal and premenarchal stages. Postmenarchal ovarian volume averages 8 cm3 with a wide range of normal volumes [11, 12]. Cystic spaces within ovaries are extremely common at all ages, usually representing follicles or functional cysts, and nearly all resolve spontaneously [11, 12]. The size and number of follicles generally increase throughout childhood.

The paired ovaries are best seen transabdominally through a fully distended bladder (Fig. 15.6). Longitudinal images can be obtained by scanning through the full bladder angled out toward the iliac vessels, and transverse images can be obtained through the bladder at around the level of the uterine fundus. In the neonate, the ovaries may be in an unsuspected higher and more ventral location within the abdomen [1, 2]. Ovarian detail is best seen transvaginally in adult patients, but endovaginal US is not used in routine pediatric practice [5].

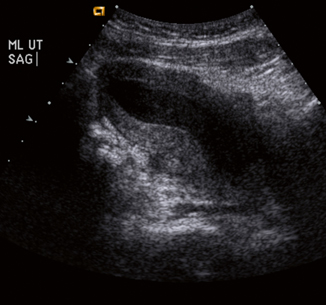

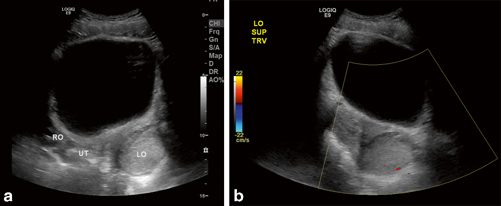

Fig. 15.6

Normal ovaries in an 18-year-old female seen through the fluid distended bladder

Ovarian Torsion

Ovarian torsion may present with acute or subacute lower quadrant or pelvic pain, pelvic US is the imaging test of choice to evaluate for the presence of torsion . Torsion is common in pediatric patients due to the relative mobility of the ovary during childhood, and even more common in patients with predisposing lesions, such as cysts or neoplasms [12]. The ovarian salvage rate is overall low, largely due to delayed diagnosis and intervention.

US findings of ovarian torsion include marked enlargement, increased or decreased echogenicity, and decreased vascularity when compared to the unaffected side [1, 12]. The absence of flow on color Doppler US is not a reliable diagnostic criterion, and this phenomenon may be explained by the dual ovarian blood supply [12]. Multiple follicles at the periphery of the ovary may also indicate torsion (Fig. 15.7) [1, 12]. The ovary may be displaced superiorly and/or ventrally, and ascites may be present [1]. The presence of a predisposing lesion, such as a cyst or neoplasm, may complicate evaluation for torsion [1, 5]. In utero, ovarian torsion may be suggested by the presence of fluid-debris levels or septations seen in previously diagnosed prenatal ovarian cysts (Fig. 15.8) [2]. When torsion is suspected and the sonographic appearance of the ovary is equivocal or not definitely normal and symmetric, emergent diagnostic laparoscopy may be required [1].

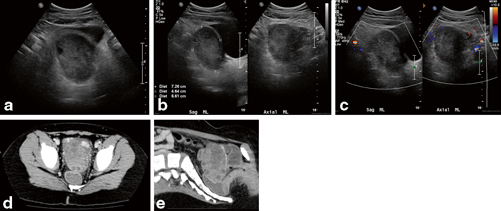

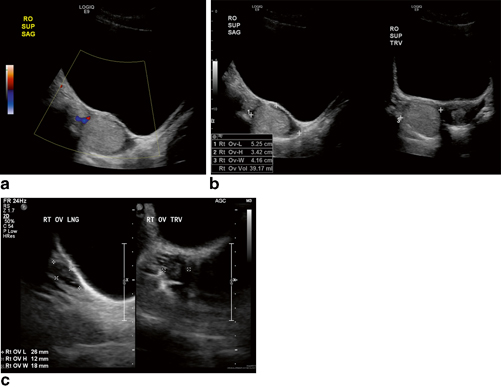

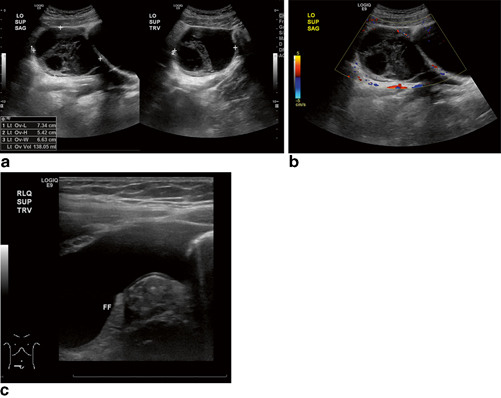

Fig. 15.7

a–e An 8-year-old female with pelvic pain initially thought to have pelvic mass, found to have enlarged left ovary with peripheral follicles, lacking internal Doppler flow, suggestion of central hypodense region found to have ovarian torsion with infarcted and gangrenous left ovary and fallopian tube intraoperatively

Fig. 15.8

a and b An 8-day-old female with bilateral ovarian cysts with fluid-debris levels and history of prenatal ovarian cysts, found to have bilateral in utero ovarian torsion on laparoscopy

Ovarian Cysts

Functional or follicular ovarian cysts are commonly seen at all ages, accounting for 60 % of the pediatric ovarian masses, and nearly all involute spontaneously [12]. These appear as uncomplicated anechoic ovarian lesions with posterior acoustic enhancement that lack internal flow on color Doppler imaging, and these may be bilateral [2, 5]. Follicular size varies, but is often greater than 1 cm in neonates, less than 5 mm in infants, and up to 4 cm after puberty, depending on the phase of the menstrual cycle [1]. Management is typically conservative with or without serial US, and cystectomy or cyst aspiration is reserved for large or symptomatic cysts, typically greater than 5 cm [5], which may predispose to torsion. Autonomous ovarian follicular cysts may secrete estradiol and result in precocious puberty, but these are also often treated conservatively with symptoms regressing spontaneously along with the ovarian cyst on serial US [5, 12].

A hemorrhagic cyst consists of hemorrhage within a functional ovarian cyst. The presence of a hemorrhagic cyst may be suggested by severe acute pelvic pain at the midpoint of the menstrual cycle. On US, the hemorrhagic cyst appears as a complex or complicated adnexal or ovarian mass with increased through-transmission and absence of internal flow on color Doppler imaging [12], which can simulate torsion (Fig. 15.9). Hemorrhagic cysts may be homogenous and mimic a solid lesion, such as an ovarian tumor, may have a fluid-debris level, or may have a “retracting” angulated internal clot [5]. Differentiation from an ovarian tumor may be difficult, as a hemorrhagic cyst may appear solid [5], and follow-up US examinations may be necessary to differentiate the two [2]. Free fluid is often observed and may be complex. Treatment is often conservative, and serial US may demonstrate the cyst becoming anechoic as it regresses in size, unlike the ovarian tumors that do not change or decrease in size (Fig. 15.10) [2]. Occasionally, the presence of active bleeding resulting in acute abdomen and/or shock may warrant surgical intervention (Fig. 15.11).

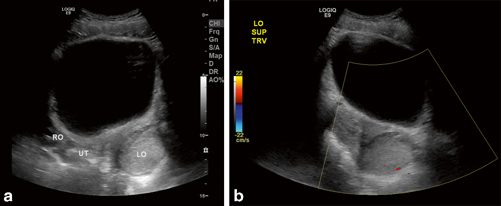

Fig. 15.9

a and b An 11-year-old female with midcycle left lower quadrant pain found to have enlarged, echogenic left ovary lacking internal Doppler flow. Initially thought to be torsion, but was unruptured hemorrhagic cyst on laparoscopy without torsion

Fig. 15.10

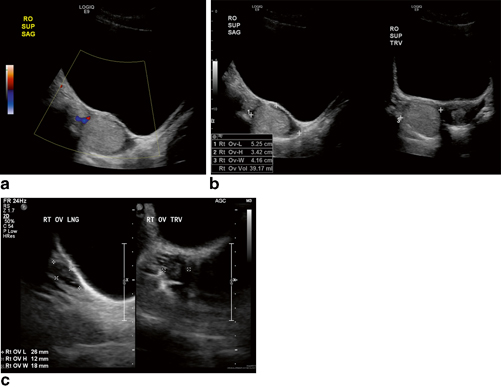

a–c A 14-year-old female with acute midcycle right lower quadrant pain found to have an echogenic lesion in the right ovary that lacked internal Doppler flow, but flow was found in normal surrounding ovarian tissue. Hemorrhagic cyst was suspected, and this completely resolved on follow-up 4 weeks later (c)

Fig. 15.11

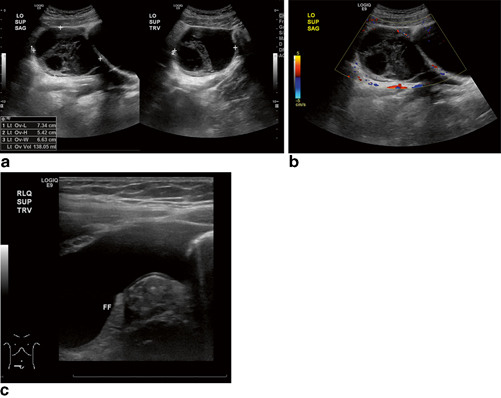

a–c A 16-year-old female with acute midcycle left lower quadrant pain found to have free fluid and large left ovarian cyst lacking internal Doppler flow. Initially thought to have ovarian cyst with torsion, was found to have ruptured hemorrhagic cyst with hemoperitoneum without torsion on laparoscopy

Ovarian Neoplasms

The clinical manifestations of ovarian neoplasms include abdominal pain, palpable abdominal or pelvic mass, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, weight loss, constipation, and urinary frequency, although lesions are also often detected incidentally in an asymptomatic patient [13]. Depending on the age of the patient, evidence of endocrine abnormality may be the presenting feature in hormone-producing tumors, including precocious puberty, menstrual irregularity, and virilization [13]. Characterization of a pediatric ovarian neoplasm is crucial to the planning of surgical resection with potential ovarian salvage and fertility preservation [13], but US alone is often inadequate in reliably differentiating benign and malignant lesions and is complimented by computed tomography (CT) or MRI [5].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree