his chapter will focus on fractures of the radial and ulnar shafts. Monteggia and Galeazzi fractures will be included. Fractures of the radius and ulna may occur together or separately. Forearm fractures account for 10% to 14% of all skeletal fractures. The mechanisms of injury may be related to a direct blow, a fall on the outstretched hand, motor vehicle accidents, and gunshot wounds. Associated injuries of the elbow and wrist are fairly common. In a large series of adult forearm fractures, 75% involved both the radius and ulna, 15% the ulna alone, and 10% the radius alone. The incidence is also increasing in adolescents around the age of puberty when activities are increasing and bone turnover due to growth spurts is more active resulting in increased cortical porosity. In the last 30 years, the incidence of forearm fractures has increased 56% in adolescent females and 32% in males.

his chapter will focus on fractures of the radial and ulnar shafts. Monteggia and Galeazzi fractures will be included. Fractures of the radius and ulna may occur together or separately. Forearm fractures account for 10% to 14% of all skeletal fractures. The mechanisms of injury may be related to a direct blow, a fall on the outstretched hand, motor vehicle accidents, and gunshot wounds. Associated injuries of the elbow and wrist are fairly common. In a large series of adult forearm fractures, 75% involved both the radius and ulna, 15% the ulna alone, and 10% the radius alone. The incidence is also increasing in adolescents around the age of puberty when activities are increasing and bone turnover due to growth spurts is more active resulting in increased cortical porosity. In the last 30 years, the incidence of forearm fractures has increased 56% in adolescent females and 32% in males.

The incidence of fractures also varies with location in both the radius and ulna. In the ulna, 13% of fractures involve the proximal third, 59% the middle third, and 28% the distal third. In the radius, 21% involve the proximal third, 61% the middle third, and 18% the distal third. Clinical examination should include assessment of soft tissues for abrasions or open wounds and evaluation of neurovascular structure to rule out compartment syndrome.

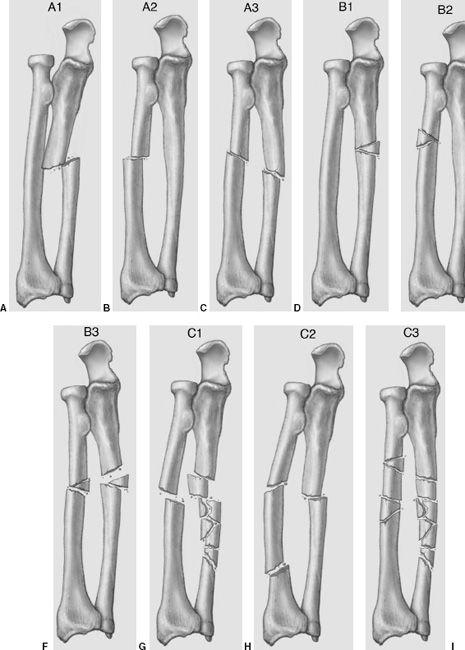

Fracture eponyms for forearm fractures such as nightstick (isolated ulnar fracture), greenstick (incomplete bowing fracture), and microfracture were reviewed in Chapter 2. The Orthopaedic Trauma Association (OTA) classification will be used in this section to facilitate discussion of treatment. Classification of diaphyseal fractures includes simple (type A), wedge or butterfly (type B), and complex (type C). The OTA has added three subcategories to each and multiple subcategories (see Fig. 12-1). The latter group addresses variations in complexity and associated dislocations of the radial head or distal radioulnar joint.

Orthopaedic Trauma Association Classification

Orthopaedic Trauma Association Classification

Type A: Simple

A1—simple ulna, radius intact

A2—simple radius, ulna intact

A3—simple fractures of both bones

Type B: Wedge (butterfly fragment)

B1—wedge ulna, radius intact

B2—wedge radius, ulna intact

B3—wedge fractures of both bones

Type C: Complex

C1—Complex ulna, simple radius

C2—Complex radius, simple ulna

C3—Complex fractures of both the radius and ulna

Two additional fractures are associated with articular dislocations. The Monteggia fracture (see Chapter 2) is a fracture of the proximal third of the ulna with an associated radial head dislocation. Monteggia fractures account for approximately 5% of forearm fractures. Type I Monteggia lesions (60%) present with anterior dislocation of the radial head and an ulnar fracture that is typically angulated anteriorly. Type II Monteggia lesions (15%) present with posterior or posterolateral radial head dislocation and the ulnar fracture is angulated more posteriorly (see Fig. 12-2). Type III lesions (20%) present with anterolateral or lateral dislocation of the radial head and an ulnar metaphyseal fracture (see Fig. 12-3). Type IV injuries (5%) present with anterior dislocation of the radial head and fractures of both the proximal radius and ulna.

Fig. 12-1 Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification for radius and ulna fractures. A: Type A1—simple ulna, radius intact. B: Type A2—simple radius, ulna intact. C: Type A3—simple fractures of radius and ulna. D: Type B1—wedge fracture of ulna, radius intact. E: Type B2—wedge fracture of radius, ulna intact. F: Type B3—wedge fractures of radius and ulna. G: Type C1—complex ulnar fracture with simple radius fracture. H: Type C2—complex radius fracture with simple ulna. I: Type C3—complex fractures of both the radius and ulna.

Fig. 12-1 Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification for radius and ulna fractures. A: Type A1—simple ulna, radius intact. B: Type A2—simple radius, ulna intact. C: Type A3—simple fractures of radius and ulna. D: Type B1—wedge fracture of ulna, radius intact. E: Type B2—wedge fracture of radius, ulna intact. F: Type B3—wedge fractures of radius and ulna. G: Type C1—complex ulnar fracture with simple radius fracture. H: Type C2—complex radius fracture with simple ulna. I: Type C3—complex fractures of both the radius and ulna.

Fig. 12-2 Monteggia fracture. Anteroposterior (AP) (A) and lateral (B) radiographs of a type II fracture with posterior dislocation of the radial head and posterior angulation of the ulnar fracture.

Fig. 12-2 Monteggia fracture. Anteroposterior (AP) (A) and lateral (B) radiographs of a type II fracture with posterior dislocation of the radial head and posterior angulation of the ulnar fracture.

Fig. 12-3 Monteggia fracture. Anteroposterior (AP) (A) and lateral (B) radiographs of a type III lesion with anterolateral radial head dislocation and anterior angulation of the ulnar fracture.

Fig. 12-3 Monteggia fracture. Anteroposterior (AP) (A) and lateral (B) radiographs of a type III lesion with anterolateral radial head dislocation and anterior angulation of the ulnar fracture.

Fig. 12-4 Galeazzi fracture. Anteroposterior (AP) (A) and lateral (B) radiographs of a distal radial fracture with dislocation of the distal radioulnar joint.

Fig. 12-4 Galeazzi fracture. Anteroposterior (AP) (A) and lateral (B) radiographs of a distal radial fracture with dislocation of the distal radioulnar joint.

The Galeazzi fracture is a fracture of the distal radius with dislocation or subluxation of the distal radioulnar joint (see Fig. 12-4). This injury accounts for 5% to 7% of forearm fractures.

SUGGESTED READING

Goldfarb CA, Ricci WM, Tull F, et al. Functional outcomes after fractures of both bones of the forearm. J Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87B:374–379.

Khosla S, Melton JL III, Dekutoske MB, et al. Incidence of childhood distal forearm fractures over 30 years. JAMA. 2003;290:1479–1485.

Orthopaedic Trauma Association Committee for Coding and Classification. Fracture and dislocation compendium. J Orthop Trauma. 1996;10:21–25.

Reckling FW, Cordell LD. Unstable fracture-dislocation of the forearm (Monteggia and Galeazzi lesions). J Bone Joint Surg. 1982;64A:999–1007.

Imaging of Forearm Fractures

Imaging of Forearm Fractures

Radiographic evaluation is essential to evaluate the position, location, and type of fracture or fracture dislocation. Images must include the elbow and wrist. Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views are obtained at a minimum. Oblique views may add additional information. The radiocapitellar relationship must be accurately evaluated. A line drawn through the mid radial head should intersect the capitellum regardless of the radiographic projection (see Fig. 12-5). Evaluation of the distal radioulnar joint is more difficult unless completely dislocated. Subluxation of the distal radioulnar joint may be difficult to evaluate on radiographs. In this setting, axial computed tomographic (CT) images in neutral, pronation, and supination will make the diagnosis. CT imaging can be performed after the other injuries are stabilized. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is rarely indicated in the acute setting but may be helpful in patients with suspected compartment syndrome or interosseous membrane injury. Injury to the interosseous membrane may result in long-term function loss. Therefore, early diagnosis and management is important.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree