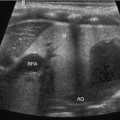

Fig. 8.1

Splenic length is measured as the maximal distance between the cranial and caudal poles of the spleen

Nomograms for splenic length as a function of age, height, weight, and body surface area have been published [1]. These show a complex, nonlinear relationship. Splenic dimensions are highly variable, but the average length ranges from 4.5 cm in 0–3-month-old to 10.5 cm in 14–17-year-old children (Table 8.1).

Age | Mean (cm) | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

0–3 months | 4.5 | 0.7 |

3–6 months | 5.5 | 0.7 |

6–12 months | 6.5 | 0.7 |

3 years | 7.5 | 0.9 |

7 years | 8.5 | 0.9 |

11 years | 9.5 | 0.9 |

15 years | 10.5 | 1.0 |

Echogenicity

In routine sonographic evaluation, healthy children demonstrate homogenous splenic echogenicity that is slightly lower than that of healthy liver tissue. Detailed discrimination between red and white splenic pulp can be accomplished by using a higher-frequency linear transducer (10–13 MHz). The white pulp is typically lower in echogenicity. It is important to remember that the lymphatic system and lymphatic follicles are not completely formed in newborns and infants, so the volume of the white pulp increases with age.

Blood Supply

A complete ultrasonographic evaluation of the spleen should always include Doppler flow studies of the surrounding and intraparenchymatous vessels. The architecture of the spleen is predominantly determined by the vascular structure. The spleen is mainly supplied by the splenic artery, which arises from the celiac trunk and in most (80 %) cases traverses along the upper border of the pancreas. Close to the hilum, it separates into two (80 %) or three (20 %) lobar arteries. These lobar arteries supply segments that typically do not form any collaterals between each other, which are important for spleen-preserving surgery. The spleen also obtains some blood from the short gastric vessels arising from the gastroepiploic artery.

Venous drainage is accomplished via the hilum into the splenic vein, which joins the mesenteric vein to form the portal vein. Therefore, splenomegaly may result from portal hypertension. Normal spleen size, however, does not rule out portal hypertension. Therefore, evaluation of the splenic drainage should always include a careful evaluation of the liver as well.

Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound

Contrast enhanced ultrasound for splenic indications has not been well studied in children. In a study that included some children, contrast enhancement increased the sensitivity for detection of splenic lacerations after blunt abdominal trauma from 59 to 96 % [2]. The main disadvantage is that intravenous microbubbles of sulfur hexafluoride gas must be infused shortly before imaging.

Anomalies

Splenomegaly

In general, the spleen must increase in size at least twofold to be clinically palpable [3]. Clinical splenomegaly is defined by the organ being palpable under the left costal angle in the midclavicular line. However, the spleen may be palpable in healthy newborns in up to 17 % of cases [4]. A good indicator for splenomegaly is the spleen–kidney ratio . The length of the spleen should not surpass the length of the kidney by 125 % [5]. Another age-independent criterion for splenomegaly is caudal extension of the spleen beyond the lower pole of the kidney. The most common reasons for splenomegaly are listed in Table 8.2.

Table 8.2

Common reasons for splenomegaly

Reason | Example |

|---|---|

Increased hemolysis | Spherocytosis, thalassemia, sickle cell anemia |

Cancer | Leukemia, lymphoma, histoplasmosis |

Autoimmune diseases | Rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematosus, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, sarcoidosis |

Infectious | Mononucleosis, leishmaniasis, malaria, tuberculosis, abscess, ehrlichiosis, echinococcosis |

Portal hypertension | Liver cirrhosis, hepatic vein obstruction (Budd–Chiari syndrome), portal vein obstruction |

Storage diseases | Gaucher, Hurler, Hunter, Niemann–Pick disease |

Benign tumors | Hemangioma, hamartoma, epidermoid cyst |

Asplenia, Polysplenia, and Topographic Anomalies

Asplenia/polysplenia, as well as the single right-sided spleen, belong to a very heterogeneous group of laterality defects including extreme variants such as total situs inversus. The exact cause remains widely unknown, but chromosomal aberrations are sometimes identified (i.e., Kartagener syndrome). Laterality defects are usually accompanied by congenital heart defects and major other anomalies such as biliary atresia , intestinal malrotation with microgastria, or isomerism of the lungs (bilateral left or right lung).

Accessory Spleen

Accessory spleens can be found in 7–20 % of patients at autopsy or in computed tomography series [6, 7]. The most common location is the splenic hilum (75 %; Fig. 8.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree