THYROID DEVELOPMENTAL ANOMALIES

KEY POINTS

- Imaging is central to proper diagnosis of thyroid anomalies.

- Computed tomography and magnetic resonance are the prime diagnostic imaging tools.

- Ultrasound is cost additive, not definitive, and should be avoided in most cases for these reasons.

- Radionuclide studies are not necessary in the vast majority of patients.

- Important associated findings that potentially alter the surgical approach are often revealed by careful imaging.

Congenital anomalies of the thyroid commonly come to imaging in both the pediatric and adult population. They are also frequently encountered as incidental findings on neck studies done for other indications. Their embryologic origin explains the diverse appearance of these anomalies on imaging studies as well as their clinical presentations. Anomalous development causes glandular underdevelopment, ectopia, and thyroglossal duct cysts (TGDCs), the latter two with potential associated functioning thyroid tissue at risk for the same diseases that might be encountered in a normal thyroid gland. These anomalies are occasionally encountered along with branchial apparatus anomalies of thymic and parathyroid origin. Their anatomic relationships and appearance on imaging studies predicts their embryologic origin and raises related treatment implications.

ANATOMIC AND DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Normal Embryology of Thyroid Development

The general mechanism of these developmental errors is incomplete development, obliteration, and/or descent of the thyroglossal duct along its tract, leaving buried cell rests trapped where they do not belong during the embryologic stage and later producing absence of thyroid tissue, a thyroglossal duct remnant, or ectopia of glandular tissue.

The thyroid gland develops as a diverticulum from the floor of the pharynx at the level of the tongue base1 (Fig. 170.1). The caudal migration of the thyroglossal duct proceeds along the thyroglossal tract to the low neck, potentially leaving duct remnants anywhere along the tract. The pyramidal lobe of the thyroid is the most common expression of this caudal migration; it is considered a normal variant (Fig. 170.2).

The vast majority of thyroid anomalies occur along this migratory pathway; however, unusual migration can result in more lateral, mediastinal, tracheal, and even cardiac deposits of normal thyroid tissue (Fig. 170.3). In the low neck, the eventual organization of juxtaposed developmental paths make the thyroid development intimately related to that of the branchial arches. The thymus, parathyroid glands, and ultimobranchial body are endodermal derivatives of the pharyngeal pouches that eventually migrate to their final position in and around the thyroid gland.1 These relationships provide a rationale for the sometimes unusual forms and associations of thyroid anomalies (Fig. 170.4).

Anatomy of Specific Interest

The anatomy of the neck is discussed in general in Chapter 149 and with regard to the thyroid and parathyroid glands in Chapter 169. It is also useful to understand the relationship of the superficial fascia of the neck to the visceral compartment and its fascial layers presented in those chapters.

The anatomy of specific interest in this chapter includes the following from cepahalad to caudal: the foramen cecum, intrinsic muscles forming the core or root of the tongue base, the hyoid bone and especially its body, the relationship of the infrahyoid strap muscles to the laryngeal skeleton, and the anatomy of the thyroid gland (Fig. 170.1).

CLASSIFICATION OF THYROID ANOMALIES

The classification of thyroid anomalies may be separated into the three basic categories that follow. It is important to remember that, while rare, malignancies may occur in ectopic tissue and thyroglossal duct remnants (Fig. 170.5). Once such an anomaly is encountered, the possibility of associated misplaced thyroid tissue giving rise to a benign or malignant tumor must be kept in mind and considered during any initial surgical approach and in any eventual surveillance plan (Figs. 170.5 and 170.6). The initial clinical presentation of these anomalies may therefore be related to growth or hemorrhage into an adenoma, or growth of a cancer. Infection of a cyst, if it communicates with the oropharynx via the foramen cecum, is a very rare presenting circumstance (Figs. 170.7 and 170.8).

FIGURE 170.1. Line diagram showing the tract of development of the thyroid tissue and various potential locations for both thyroglossal duct cysts and glandular ectopias. (From Sadler TW, ed. Langman’s medical embryology. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006: 279, with permission).

FIGURE 170.2. Radionuclide studies showing variations of pyramidal lobes in two patients. A, B: Patient 1. Panoramic (A) and close-up (B) views of a pyramidal lobe (arrow). C: Patient 2 with a thicker pyramidal lobe (arrow) that is slightly eccentric, coming more from the right lobe than the left.

Agenesis and Underdevelopment

Agenesis and underdevelopment are anomalies due to failure of median thyroid anlage and “athyrosis” or absence of the gland. Patients will present with hypothyroid manifesting early in life as cretinism. Failure of one side to develop, usually the left, is usually found incidentally (Fig. 170.9).

Ectopia

Ectopia may be suprahyoid (Figs. 170.10–170.14), infrahyoid (Figs. 170.3 and 170.15–170.17), intratracheal, or mediastinal, with the latter related to an unusual exaggeration of inferior descent of the thyroglossal duct beyond the usual tract. Lateral ectopia should never be in nodes, although it has been suggested that this may occur. Far more likely than not, thyroid tissue in nodes is due to indolent metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer.

An ectopia may present as a palpable midline or paramedian mass or sometimes one more laterally (Figs. 170.10–170.17). They are also found coincidentally. Those of the tongue base usually present with dysphagia and/or odynophagia and a submucosal mass on physical examination (Figs. 170.10 and 170.12).

Thyroglossal Duct Remnants

TGDCs most frequently present as anterior, midline, or paramedian neck masses (Figs. 170.18–170.22). A TDGC will present as a mass mainly in pediatric patients and young adults. They are more commonly seen as incidental findings in older patients having computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) studies of the neck for other reasons (Figs. 170.18–170.22).

TDGC anomalies are the most common visceral compartment abnormality that presents as a neck mass. The cysts present as suprahyoid masses (Fig. 170.18) at the level of the hyoid (Fig. 170.19), most frequently infrahyoid (Figs. 170.20–170.22). The tract to the foramen cecum from the tongue base may lie anterior or posterior to the hyoid bone (Figs. 170.18 and 170.19). The differential diagnosis is usually not in serious doubt clinically, but CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can confirm the diagnosis and differentiate it from other neck masses that can occasionally arise in the anteriorly and paramedian (Fig. 170.23).

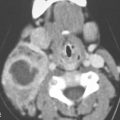

FIGURE 170.3. A–D: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography study of a patient with an infrahyoid ectopia of the thyroid gland shown by the arrows in all images. In (B), there is thyroid tissue not attached to the main ectopic glandular tissue, demonstrating the potential for all migrational abnormalities of the thyroid gland to result in disconnected lateral ectopic tissue (arrowheads). In (C), there are multiple small cysts within the ectopic tissue, suggesting that such ectopic tissue can develop abnormalities that might occur in normally positioned thyroid tissue (arrowheads).

Anomalies Involving the Thymus and Parathyroid Glands

The third and fourth branchial pouches are identified by the proliferation of endoderm with that epithelial growth developing into the thymus and parathyroid glands. Third and fourth branchial pouches anomalies therefore are histologically classified by the gland of origin. These are illustrated in Chapter 153.

FIGURE 170.4. Two patients with thyroid anomalies associated with abnormalities of branchial origin. A: Patient 1. T2-weighted magnetic resonance showing a portion of a thymoma arising in ectopic thymic tissue in the lateral neck (arrowheads) associated with intrathyroidal thymic tissue (arrow). B, C: Patient 2. Ultrasound examination of a patient with an intrathyroidal parathyroid adenoma (arrow).

FIGURE 170.5. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography study of a patient with cancer arising in ectopic thyroid tissue within a thyroglossal duct cyst. A: The abnormal paramedian thyroid tissue invades the floor of the mouth on the left side (arrow) with a suggestion of focally abnormal lymph nodes (arrowhead). B: Cephalad extension of the tumor well into the floor of the mouth (arrows). C: Continued extension of the thyroid cancer deeper into the floor of the mouth (arrow) with clearly abnormal level 2 lymph nodes manifest by discreet foci of enhancement and low density (arrowheads) confirming that these are metastatic lymph nodes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree