THYROID: NODULES AND MALIGNANT TUMORS

KEY POINTS

- The incidental discovery of thyroid nodules must be reported, but this creates potentially large medicoeconomic burdens with little return in improved longevity and/or quality of life relative to the costs incurred. Therefore, follow-up plans must be rational and not based only on the nodule characteristics.

- Imaging with magnetic resonance and computed tomography is very useful to determine the primary tumor extent and regional nodal metastases.

- Fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) has a role that should be customized for each patient.

- Imaging aids significantly in treatment selection and surveillance for recurrence.

INTRODUCTION

Thyroid Nodule Evaluation

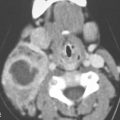

Thyroid nodules are commonly detected on physical examination and even more commonly identified as incidental findings on computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), radionuclide studies, and ultrasound examinations of the neck done for other purposes than evaluating the thyroid gland (Fig. 172.1). Risk factors that strongly suggest necessary biopsy or removal include a thyroid mass in a child or young adult, history of neck irradiation, family history of thyroid cancer, rapid growth, lymphadenopathy, or tracer accumulation on a fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) study (Fig. 172.1E–G). An older patient with a relatively soft, multinodular gland that has been stable for many years represents the other end of the spectrum. In the middle are sets of imaging criteria that are aimed at follow-up strategies in less clear-cut circumstances. In reality, many thyroid cancers will have no impact on a person’s life (Fig. 172.1). The socioeconomic and medical dilemma of how to manage incidentally discovered thyroid nodules is discussed in subsequent sections. It is not a simple issue at this point in time.

Thyroid Cancer Evaluation

Thyroid carcinoma is a relatively uncommon disease of highly variable clinical behavior. Many of these cancers will never threaten the life expectancy of the patient even if left untreated (Fig. 172.1A–D). Still, imaging is important for proper medical decision making, especially in cancers that have spread beyond the gland capsule.

ANATOMIC AND DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Embryology

The developmental pathway of the thyroglossal duct cyst described in more detail in Chapter 170 contributes to rare cases of ectopic origin of mainly differentiated thyroid cancer (Figs. 170.5 and 170.6). Although rare, such cancer may occur in thyroglossal duct remnants or glandular ectopia anywhere along this migratory pathway from the foramen cecum at the upper tongue base to the isthmus of the gland.

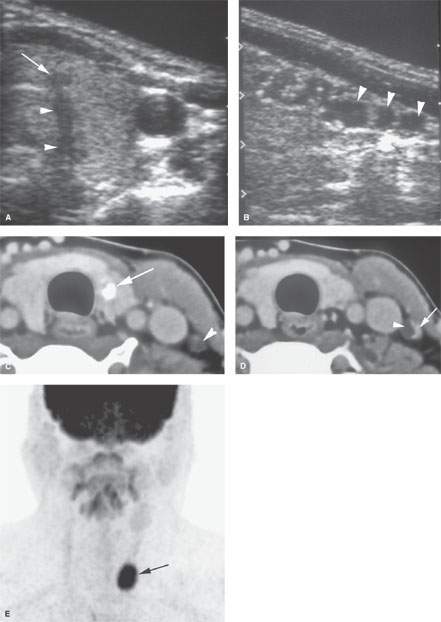

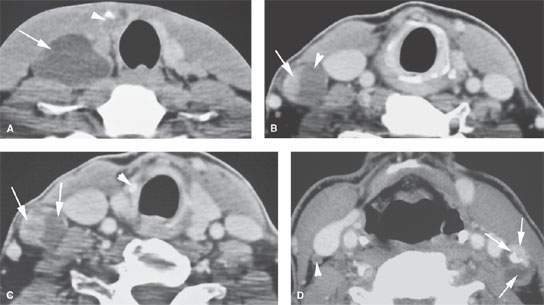

FIGURE 172.1. A–D: A patient having an ultrasound examination for a parotid lesion. The neck was also studied. In (A), a focus of abnormality (arrow) in the left thyroid lobe at the junction with the isthmus shows acoustical shadowing (arrowheads). In (B), sagittal ultrasound shows small cystic-appearing changes within the cervical lymph nodes (arrowheads). In (C) and (D), a computed tomography study was done for further evaluation. In (C), there is a calcification in the left thyroid lobe, which was believed to be a carcinoma (arrow) producing metastases to the lower neck nodes (arrowhead). In (D), an additional lymph node is seen with a cystic (arrowhead) and solid enhancing component (arrow) typical of thyroid metastases. (NOTE: The patient allowed a biopsy of the thyroid lesion, which was negative for cancer. Follow-up after 20 years showed no evidence of progression of this disease without treatment, which is most likely attributed to a very low grade papillary carcinoma of the thyroid gland.) E–G: A patient with tongue base cancer. The coronal fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) image in (E) shows a focal area of fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) uptake in the left lower neck (arrow). It would be very unusual for a right-sided tongue base cancer to metastasize to the lower and contralateral neck without any other lymph nodes involved. The axial, non–contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography (CT) (F) and the fused positron emission tomography/CT (G) images show that this uptake localizes to a thyroid adenoma (arrow in F and G).

During development, both lymphoid elements and squamous cells may be incorporated or are otherwise present in the gland, likely accounting for the rare primary squamous cell carcinomas of the gland that have occurred in the absence of a known primary tumor elsewhere in the head and neck. This may also be the source of primary thyroid lymphoma as well, although disease arises as a late complication of chronic thyroiditis.

Rests of normal ectopic thyroid tissue may be found in the lateral neck. These can be mistaken for metastatic disease. When found in cervical nodes, such deposits should most safely be considered metastases from well-differentiated thyroid cancer rather than a developmental condition.

Applied Anatomy

The key anatomy of the thyroid gland and surrounding structures in the region that must be understood to adequately evaluate nodules and known thyroid cancers includes the following:

With regard to the evaluation of thyroid nodules:

- Normal texture of the thyroid gland at ultrasound and the normal appearance of lymph nodes at ultrasound (Figs. 172.1–172.4 and Chapters 4 and 149)

With regard to local extension and involvement of important surrounding structures:

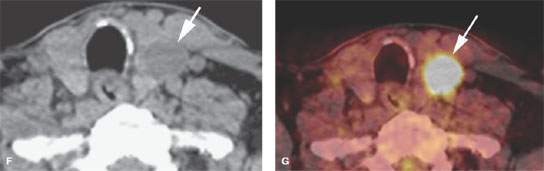

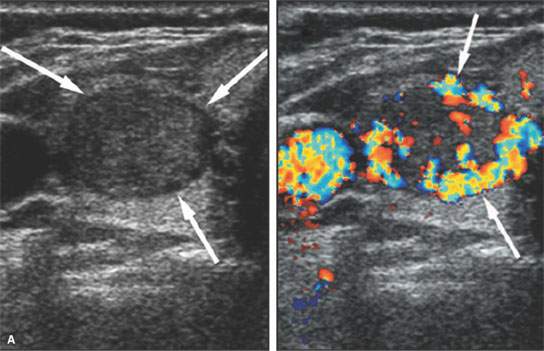

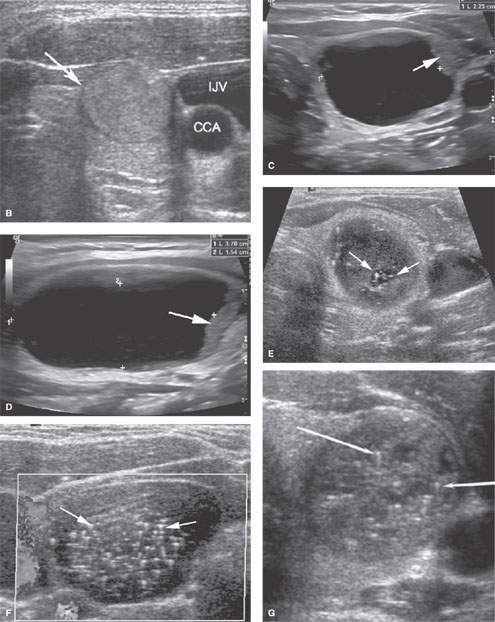

FIGURE 172.2. Various ultrasound findings in patients with a thyroid mass. A, B: Patient 1. In (A), the two-part figure on the left shows a thyroid adenoma with a peripheral halo sign (arrows) in a nodule that is very well circumscribed. The companion color flow image shows a predominately peripheral pattern of flow suggestive of benign disease. This proved to be a benign adenoma. In (B), an axial image confirms the homogeneous texture of the well-circumscribed nodule, the halo sign (arrow), and the well-circumscribed nature of this benign adenoma. (CCA, common carotid artery; IJV, internal jugular vein.) C, D: Patient 2. Axial and sagittal images, respectively, showing a sonolucent nodule with some minimal solid tissue at its periphery (arrows). This was shown to be a large colloid cyst. E, F: Patient 3. Axial and sagittal images, respectively, show that the well-circumscribed nodule has slightly indistinct margins in the axial view and contains extensive psammomatous calcifications. The nodule was found to be a benign adenoma. G: Patient 4 shows a well-circumscribed nodule with a halo sign and numerous psammomatous calcifications. Biopsy showed a benign adenoma. H, I: Patient 5 to illustrate the variability of nodules that may be seen in a patient. In (H), there are somewhat ill-defined, poorly marginated (arrows) nodules and an echogenic nodule that is fairly well circumscribed with a peripheral halo (arrowhead). In (I), the superior and inferior dimensions of one nodule exceed the anterior to posterior dimensions (arrow) in one of the more anterior nodules. All of these nodules were benign. Some were biopsied, while others were unchanged over years of follow-up. J: Patient 6. Multiple mixed solid and cystic nodules, most under 1 cm throughout the gland. The white arrow shows a fairly well circumscribed margin, while the black arrow shows slightly indistinct margins. The asterisk shows a small nodule with indistinct margins and an irregular internal echo pattern. The heterogeneity of nodules in the thyroid gland points out the difficulty in establishing effective follow-up treatment plans to completely allay patients’ fears of potential malignancy. It also points out to some degree the futility of aggressive biopsy of nodules in all patients given their ubiquitous nature in the population.

- Complete understanding of the anatomy of the gland itself (Chapter 169) and the relationship of the thyroid gland to the organs including the larynx, trachea, hypopharynx, and esophagus (Chapters 169, 201, 209, 215, and 221)

- Developmental anatomy of the thyroglossal duct as it relates to the tongue base and visceral compartment of the neck (Chapter 170)

With regard to invasion of bony structures:

- Virtually never occurs in thyroid cancer, but adjacent cervical spine, clavicle, and manubrium of the sternum are rarely invaded in anaplastic carcinoma

With regard to possible routes of perineural and/or perivascular spread or functional deficits that may arise from involvement of surrounding nerves:

- Course of the vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerves, cervical sympathetic chain, and carotid sheath (Chapter 149); also, appearance of the larynx when the vagus or recurrent laryngeal nerves have been disrupted

With regard to regional lymph node involvement:

- Retropharyngeal nodes and cervical nodes (mainly levels 2 through 5 and in particular level 6) (Fig. 172.5); rarely involved are level 1, parotid area, posterior neck, and facial lymph nodes (Chapters 149 and 157)

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

The thyroid gland is studied in essentially the same manner as the infrahyoid neck is evaluated with MRI and CT. The principles of using these studies were reviewed in Chapter 149. Specific problem-driven protocols for MRI and CT are presented in Appendixes A and B.

Ultrasound is of enormous value in the evaluation of the thyroid gland. The specific techniques are described in Chapters 4 and 169.

The approach with radionuclide studies depends on the aim of the examination. Most of the current usage is limited to known or suspected thyroid cancer by a combination of radioiodide and FDG-PET for cancer evaluation. Specifics of the use of this physiologic imaging in relation to anatomic imaging are discussed in general in Chapter 5. The use of radionuclide studies in thyroid cancer and nodule evaluation needs to be carefully integrated with specific clinical decision making on a case-by-case basis so that resources are appropriately expended.

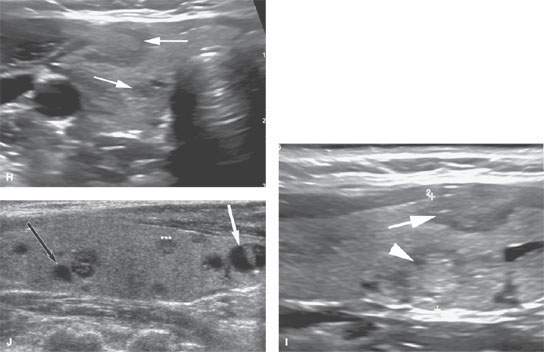

FIGURE 172.3. Two patients with ultrasound findings suggestive of cancer. A: Patient 1 has a nodule with very irregular margins (arrows) and calcifications with some shadowing (arrowheads). Biopsy showed this to be malignant. B–D: Patient 2 showing an abnormal nodule in association with the lower pole of the thyroid gland (arrow) that did not have any particular suspicious findings, but the patient was found to have left vocal cord weakness. In (C), the contrast-enhanced computed tomography study shows a low-density abnormality either due to a thyroid nodule or a level 6 lymph node (arrow). In (D), the left true vocal cord is seen to be atrophic (arrow). (NOTE: The nodule proved to be a level 6 metastatic lymph node due to papillary carcinoma within the left lobe of the thyroid gland. The cancer was found at the time of pathologic sampling of the gland after its removal.)

Pros and Cons

Thyroid Nodule Evaluation

In at-risk populations, the main diagnostic tools for triaging patients for surgery are ultrasound and needle biopsy. Radionuclide scans are usually not helpful since many nodules are hypofunctioning or “cold” relative to normal thyroid tissue. Ultrasound is used to determine whether the nodule is solitary or one of several or many. If a nodule is >75% cystic, it is likely to be benign. Nodules <10 mm are typically not biopsied. A nodule >1 cm with >25% solid component may be followed with ultrasound or biopsied, but that is not entirely foolproof1 (Fig. 172.6A–D). Such a follow-up protocol creates substantial economic burdens on the health care system for many of the thyroid cancers that, even when discovered as such, would not affect the quality of life or longevity of the patient if left alone (Fig. 172.1). The debate over this problem is considerable and reasonable.2 It will not be settled for some time, but perhaps will be by some emerging technology that will still have a cost burden for a problem that is largely, in reality, a nonthreatening problem.

Additional ultrasound parameters can be added to the risk assessment about which nodules need to be biopsied, but these still must be kept in a clinical context.3–8 A nodule in a 15 year old certainly has a different meaning than one in an 80 year old clinically, but does it ethically?9 Such additional factors include vascular characteristics of thyroid nodules, with those with perinodal vascular prominence being less at risk for malignancy than those with more central hypervascularity. These flow characteristics may also be added to pathoanatomic features including a halo, microcalcifications, relative dimensions in cross section, and echogenicity to improve the predictive models (Figs. 172.1–172.3 and 172.6A–D).

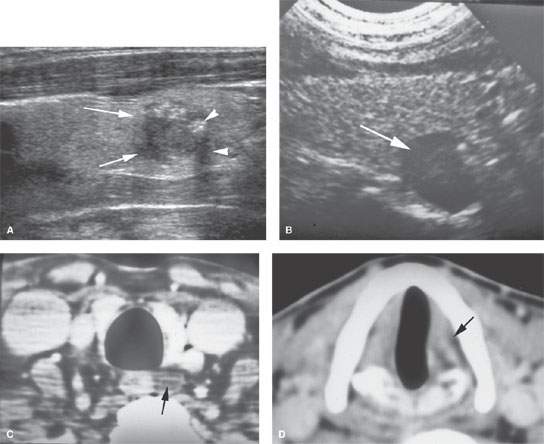

FIGURE 172.4. Incidentally discovered thyroid adenoma on computed tomographic angiography to show the typical pattern of adenomas with regard to enhancement. A: Axial study showing the adenoma in the left thyroid lobe and a slightly enlarged inferior thyroid artery likely providing some supply to the adenoma (arrow). B: Coronal reformation showing a predominately peripheral enhancement pattern reflecting the margin of the adenoma and the compressed thyroid tissue as well as the enlarged related vascular pedicle (arrow). Sagittal reformation demonstrating the same peripheral enhancing pattern in (C) that is hard to tell from the iodine concentrating in the compressed gland (arrows in D). It is easier to identify peripheral enhancement in nodules on color flow ultrasound images. E: In another patient, a colloid cyst on contrast-enhanced computed tomography in another patient showing a sharper margin with the compressed glandular tissue, but a peripherally enhancing nodule really cannot be excluded as an option.

FIGURE 172.5. A series of patients with low neck adenopathy eventually proven to be due to thyroid carcinoma. The primary tumors were #1 cm in all three patients. A: Patient 1 presenting with an almost entirely cystic mass low in the neck (arrow) that subsequently was shown to be due to a small carcinoma in the right lobe (arrowhead). B, C: Patient 2 showing metastatic adenopathy at level 4 that had both cystic (arrowhead) and solid enhancing (arrow) components. In (C), the cystic and solid enhancing components of the metastases are again visible (arrow), and the small responsible primary tumor was identified (arrowhead). D: Patient 3 with a thyroid carcinoma and a level 3 node on the left side demonstrating a focal enhancing nodule, calcification, and cystic components and a small node showing a tiny focal metastases in the right neck (arrowhead). (NOTE: A patient presenting with nodes in the low neck of this morphology should be presumed to have thyroid cancer even if the primary is not definitely visible on any imaging study.)

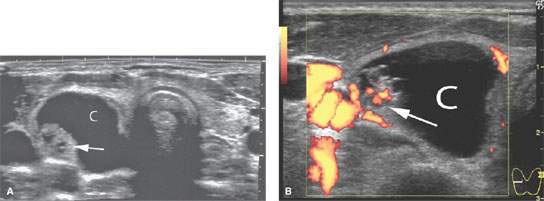

FIGURE 172.6. A series of patients in the next several figures to demonstrate a progression of locally invasive characteristics and other imaging factors that suggest malignancy. In the two patients in this figure, the cancers are contained within the gland capsule. A–E: Patient 1. In (A), transverse ultrasound shows a right thyroid mass that is mostly composed of a cyst (C) but with a solid nodule (arrow). The mass is >75% cystic, which suggests that it should be benign. In (B), a color flow image to correlate with (A) shows a more central enhancing pattern that suggests malignancy but is not specific. In (C), the non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) image shows the nodule (arrow) within the cyst (C) that likely contains somewhat proteinaceous material and a suggestion of possible extension outside the gland capsule by the solid component (arrowhead). In (D), the contrast–enhanced T1W fat-suppressed image shows the peripherally enhancing nodule (arrow) with no definite evidence of spread beyond the gland capsule. In (E), the T2-weighted image shows the irregular border of the mass and the cyst (C) to be of low signal intensity, suggesting that it might contain a very highly proteinaceous material and/or blood products. (NOTE: This proved to be thyroid carcinoma, although in looking at the overall findings, they are somewhat ambiguous with regard to prediction of this being a benign or malignant lesion based on criteria used to make such judgments.) F: Patient 2 with a generally enlarged thyroid gland. Ultrasound shows the gland to be enlarged with a diffusely abnormal texture pattern and no definite evidence of disease extending beyond the gland, although the trachea is displaced posteriorly. This turned out to be thyroid lymphoma.

Thyroid Cancer Evaluation

CT and MRI suggest malignancy when there is extraglandular extension and/or lymph node metastasis (Figs. 172.5–172.13). Such imaging is most useful for establishing the extraglandular extent of a tumor prior to surgery. These studies map tumor relative to the critical anatomy in the low neck and thoracic inlet. Regional neck and mediastinal nodes are also evaluated by CT and MRI. Level 6, superior mediastinal, and retropharyngeal nodes cannot be evaluated by physical examination.

MRI is the primary study for establishing the local extent of a known cancer because it is superior to CT at showing esophageal and tracheal wall invasion; this local extension will likely much more influence therapy than nodal staging (Figs. 172.5–172.11). Also, iodinated contrast is necessary for a reasonably definitive CT study, and this may interfere with plans for diagnostic and therapeutic use of iodine-based radionuclides.

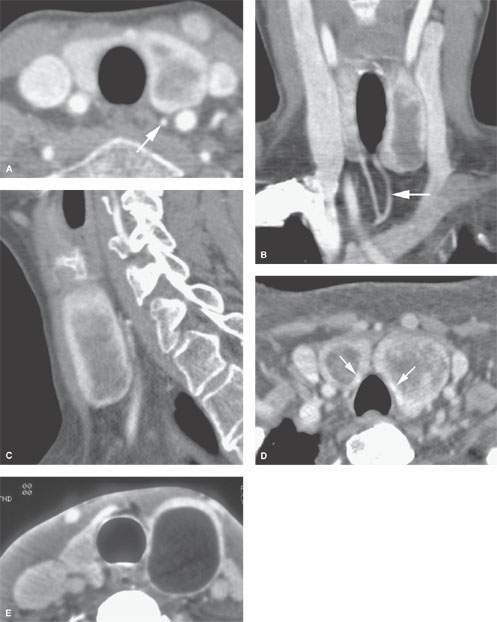

Any cancer discovered by ultrasound >3 to 4 cm in size may be studied with MRI and/or CT because of the likelihood of capsular penetration unless ultrasound assures that the mass is completely surrounded by normal thyroid tissue. Any tumor potentially associated with vocal cord weakness, dysphagia, or airway symptoms should also likely be imaged with MRI and/or CT (Fig. 172.6).

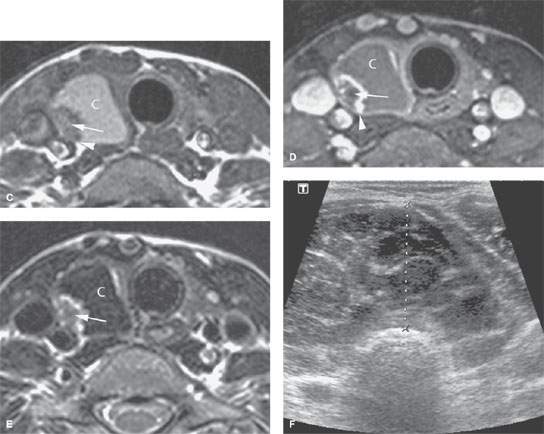

FIGURE 172.7. A patient with a palpable left thyroid nodule. Computed tomography study showing the mixed cystic, solid, and calcified nodule growing eccentrically beyond the margins of the gland. This proved to be papillary carcinoma. There is no definite evidence of related lymphadenopathy.

The specific uses of MRI or CT include the following:

- Local spread: Invasion of the tracheal cartilages connecting membranes and the membranous posterior wall is best determined by magnetic resonance (MR) (Figs. 172.6–172.13). Invasion of the esophageal muscular wall is best determined by axial T2-weighted and contrast-enhanced MR images (Fig. 72.12). Invasion of the laryngeal framework is best determined by CT but may be detectable by MRI (Fig. 172.13).

- Neurovascular involvement: The relationship of tumor to the carotid artery, course of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, and other major neurovascular structures in the low neck and thoracic inlet is best determined by MRI and/or CT (Fig. 172.14).

- Regional nodes: MRI and CT are useful in level 6, superior mediastinal, and retropharyngeal groups, none of which can be palpated; of these, only level 6 is accessible to ultrasound (Figs. 172.6–172.13). CT has a modest advantage over MR in detecting nodal metastatic disease.

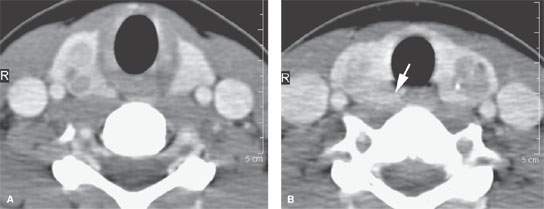

FIGURE 172.8. A patient with known multiple endocrinopathy syndrome. This computed tomography study shows multiple nodules (A, B) within the thyroid gland. The nodules are in many places ill defined, and findings in the right tracheoesophageal groove suggest spread beyond the gland capsule (arrow in B). The findings proved to be due to multifocal medullary carcinoma present in both lobes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree