Clinical Presentation

The patient is a 19-year-old college basketball player with a 4-month history of progressively worsening low back pain, radiating into the thoracic region and also into the right buttock and thigh. The pain is not relieved by rest, aspirin, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Back strengthening exercises over the past 6 weeks have not relieved his pain whatsoever. He reports a tingling sensation in both feet when recumbent at night. No lower extremity weakness on examination.

Imaging Presentation

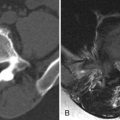

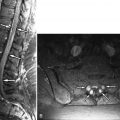

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the lumbar spine reveals evidence of L4-5 intervertebral disc degeneration and a moderate-sized midline L4-5 disc herniation that causes ventral thecal sac deformity ( Figs. 26-1 and 26-2 ) . A lumbar spine computed tomography (CT) scan was obtained because of deformity of the posteroinferior corner of the L4 vertebral body and probable avulsion fracture of posterior margin of the L4 vertebral body seen on the MR scan. The CT scan confirms an avulsion fracture of the posteroinferior corner of the L4 vertebral body associated with L4-5 disc herniation ( Figs. 26-3 and 26-4 ) .

Discussion

In children and adolescents, traumatic disc herniations usually involve the unused ring apophysis. Traumatic disc herniations and ring apophyseal injuries in young persons more commonly occur in the lumbar region, although occasionally they may occur in the cervical or thoracic spine. The injury most commonly involves the inferior rim of the L4 endplate or the superior rim of the S1 endplate ( Figs. 26-1 to 26-8 ) . Most traumatic herniations in children or adolescents occur in athletes or those who perform activities that subject the spine to repetitive stress. Some have suggested that there may be a congenital insufficiency of the ring apophysis that predisposes one to this injury. Motor vehicle accidents or other acute traumatic events can also damage the ring apophysis.

In normal persons younger than 6 years, the ring apophysis is a cartilaginous ring that develops in an annular depression along the superior and inferior margins of the vertebral body peripherally. The cartilaginous ring apophysis develops separate from the vertebral epiphysis, and this ring may be lacking posteriorly. The outer annular fibers of the intervertebral disc (Sharpey’s fibers) and some fibers of both the anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL) and posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) attach to this cartilaginous ring. Because Sharpey’s fibers, the ALL, and the PLL normally exert tractional forces on the ring apophysis, it is sometimes referred to as a traction apophysis . The radiolucent cartilaginous ring apophysis begins to calcify at age 6, begins to ossify at age 13, and begins to fuse to the vertebral body at age 17. Complete fusion of the ring apophysis to the vertebral body occurs between the ages of 18 and 20 years. Trauma to the outer discovertebral margin results in accentuation of the traction forces upon the apophyseal ring, which can cause an avulsion fracture, or at the very least, can hamper or prevent fusion of the ossified ring apophysis to the vertebral body.

Alternatively, forced flexion and rotation of the spine can produce radial (shearing) forces that disrupt the ring apophysis. This mechanism is believed by some to be the most common mechanism of injury in anterior ring apophysis injury and is most common in athletes, especially gymnasts and wrestlers. This can cause anterior vertebral rim compression deformities of variable size or a tiny triangular-shaped ring apophyseal fragment that are commonly referred to as a limbus vertebra ( Figs. 26-9 and 26-10 ) . These may be located in the lumbar, thoracic, or cervical spine. Larger anterior ring apophyseal fragments are more likely to be caused by avulsion of the ring apophysis, and most commonly occur in the lumbar region. These can be produced by traumatic anterior vertebral compression or by anterior disc herniations.