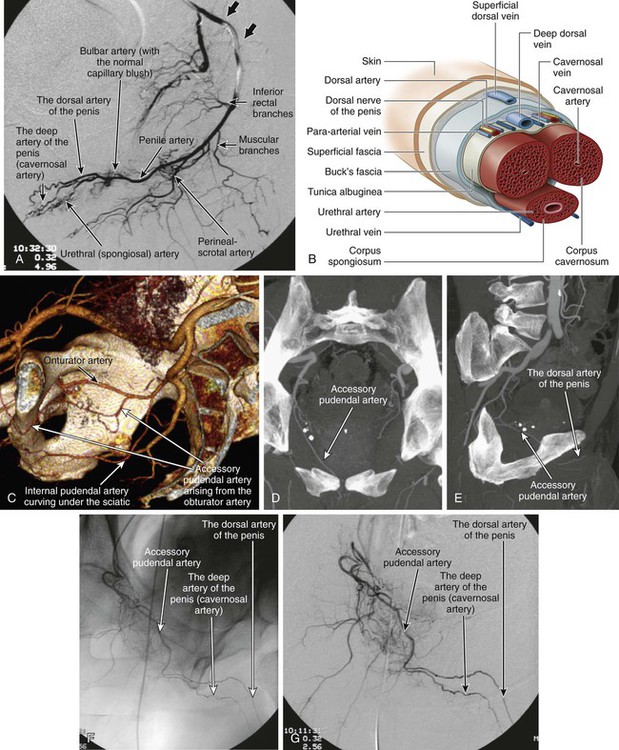

Tiago Bilhim, João M. Pisco, Max Kupershmidt and Kenneth R. Thomson Priapism is a pathologically persisting erection of the penis not associated with sexual stimulation. It is a result of imbalance of arterial inflow and venous outflow involving the corpora cavernosa. The incidence in the general population is low, between 0.5 and 2.9 per 100,000 person-years, and is higher in patients with sickle cell anemia and in men using intracorporal injections.1,2 First-line treatment is aspiration that confirms the diagnosis and at the same time decompresses. This is followed by irrigation with a sympathomimetic pharmaceutical agent and, if necessary, a surgical shunt. The management is slightly different but follows the same principles for the sickle cell anemia variant of veno-occlusive priapism.3,4 • Less common than the low-flow type; in adults, 80% to 90% have a single fistula causing the priapism, but in children, 50% have multiple fistulas.3–5 There is unregulated blood flow in an arteriolacunar (not arteriovenous) fistula between one of the terminal branches of the internal pudendal artery (most commonly the cavernosal artery) and lacunar spaces of the corpora cavernosa. The bulbar and dorsal penile arteries are less frequently involved. Venous outflow is not restricted, because there is no compression of subtunical veins, normally produced by neural stimulation; hence, there is a constant state of inflow/outflow without pooling of blood. Shearing forces on the endothelium cause release of increased levels of nitric oxide and activation of the cyclic guanosine monophosphate pathway, resulting in relaxation of smooth muscle.6–8 Unlike the low-flow/occlusive type, there is no ischemia or pain, and hence it is not an emergency. The onset is usually delayed after injury, but typically it is clinically evident within 72 hours.9 Aspiration of the cavernosa reveals arterial blood. Doppler studies show normal or high velocities in cavernosal arteries. The actual site of the arteriolacunar fistula can usually be accurately determined.3,4 Erectile dysfunction is defined as inability to reach or maintain erection sufficient for satisfactory sexual performance.10 ED is commonly associated with diabetes mellitus (threefold increased risk of ED), hypertension, vascular disease, dyslipidemia, hypogonadism, and depression. A normal sexual erectile response results from the production of nitric oxide from endothelial cells after parasympathetic stimuli. Nitric oxide causes smooth muscle relaxation, which leads to arterial influx of blood into the corpus cavernosum, followed by compression of venous return, producing an erection. This neurovascular function must be integrated with sexual perception and desire.12 Other smooth muscle relaxants (e.g., prostaglandin E1 analogs and α-adrenergic antagonists) can cause sufficient cavernosal relaxation to result in erection. Many of the drugs that have been developed to treat ED act at this level.13 Vascular causes of ED may be arterial and/or venous, and these are the ones amenable to endovascular treatment. Generalized penile arterial insufficiency may result from stenotic arterial lesions of the internal pudendal arteries or from microangiopathy of the arteries of the corpora cavernosa. Failure of the veins to close completely during an erection (veno-occlusive dysfunction) may occur in men with large venous channels that drain the corpora cavernosa, and may be studied by cavernosography.13 Evidence is accumulating in favor of ED as a vascular disorder in the majority of patients.14 Up to 70% of men with ED remain undiagnosed and untreated.15 ED has an effect equal to or greater than the effects of family history of myocardial infarction, cigarette smoking, or measures of hyperlipidemia on subsequent cardiovascular events.16 All patients with ED should be considered for screening for undetected cardiovascular disease. The AUA recommends that the initial evaluation of ED include a complete medical, sexual, and psychosocial history.17 History and physical examination are sufficient to make an accurate diagnosis of ED in most cases.12 The five-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function Questionnaire (IIEF-5) is a validated survey instrument that can be used to assess the severity of ED symptoms.18 Although erectile function can improve after vascular reconstructive surgery or endovascular angioplasty of the internal pudendal/penile arteries,20–23 there is still very little evidence to recommend vascular imaging studies and therapies for ED in the general population. More rigorous trials are needed to prove short- and long-term effectiveness.19 Duplex sonography with pulsed Doppler analysis (with and without dynamic erection studies with vasoactive substances) and nocturnal penile tumescence (NPT) are usually performed as first-line studies. Evaluation of these vasculogenic factors ultimately depends on cavernosography and internal pudendal angiography.24 The internal pudendal artery arises from the anterior division of the internal iliac artery, with a typical trajectory curving under the sciatic notch that enables easy recognition.25 The artery enters the perineum via the lesser sciatic foramen and runs along the lateral wall of the ischiorectal fossa between the split layers of the obturator fascia in the Alcock canal to the inferior pubic ramus (Fig. e81-1). It gives rise to the following collateral branches, in order: • Inferior rectal (or inferior hemorrhoidal) branches at the level of the ischial tuberosity • Perineal-scrotal artery, supplying the perineal muscles, structures between anus and scrotum, skin and dartos tunic of the scrotum Some authors consider the artery to be called the penile artery from here on, giving rise to: • Bulbar artery supplying the bulb of the urethra, posterior corpus cavernosum, and bulbourethral glands (with the normal capillary blush seen within the bulbar spongiosa) • Urethral (spongiosal) artery supplying the corpora spongiosa and providing anastomoses with the dorsal artery of the penis at the glans penis There are two terminal branches: • The deep artery of the penis (cavernosal artery), which divides into helicine arteries that enter the lacunar spaces almost at right angles from the cavernosal artery • The dorsal artery of the penis, the other terminal branch supplying the glans penis and prepuce. Its course lies outside the tunica albuginea. Thus, the penis has three pairs of arteries: two urethral arteries that run on either side of the penile urethra in the corpus spongiosum, two cavernosal arteries, each running on the center of the corpus cavernosum, and two dorsal arteries of the penis running on either side of the dorsum of the penis between the tunica albuginea and Buck fascia, near the dorsal nerves of the penis.26 The most common anatomic variation is the accessory pudendal artery, which arises from the internal iliac or internal pudendal arteries within the pelvis and passes below the pubic symphysis along the anterior-lateral aspect of the prostate, below the bladder (see Fig. e81-1). This branch most frequently replaces the dorsal artery of the penis and deep branches of the internal pudendal artery (with the internal pudendal artery terminating as the bulbar artery or with perineal branches).

Treatment of High-Flow Priapism and Erectile Dysfunction

Priapism

Low-Flow/Ischemic/Veno-occlusive Priapism

Incidence

Management

High-Flow/Nonischemic/Arterial Priapism

Incidence

Pathophysiology

Clinical Presentation

Erectile Dysfunction

Pathophysiology

Clinical Presentation

Management

Vascular Studies in the Patient with Erectile Dysfunction

Relevant Anatomy

Arterial Anatomy

Treatment of High-Flow Priapism and Erectile Dysfunction