Abstract

Trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome) is the second most common autosomal trisomy in newborns. More than 90% of cases are the result of maternal nondisjunction of chromosome 18. Fetuses with trisomy 18 have significant structural abnormalities that are detected on prenatal ultrasound. Findings include cardiac abnormalities, ventriculomegaly, lemon-shaped skull, posterior fossa abnormalities, increased nuchal translucency, growth restriction, and limb and facial defects. The most common minor ultrasound marker is a choroid plexus cyst. Trisomy 18 is almost always lethal. The few infants that survive have severe physical and neurocognitive defects.

Keywords

choroid plexus cyst, ventriculomegaly, clenched hands

Disorder

Definition

Trisomy 18, also called Edwards syndrome, results from the presence of an extra copy of chromosome 18.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Trisomy 18 is the second most common autosomal trisomy among live-born fetuses after Down syndrome. The incidence of trisomy 18, 0.6–2.5 : 10,000, is considerably lower than that for Down syndrome. It is associated with multiple congenital anomalies, profound neurologic damage, and severe developmental delays in surviving neonates.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The incidence of trisomy 18 is increased in women with advanced maternal age. Most cases of trisomy 18 are the result of maternal meiotic nondisjunction (more than 90%). Paternal meiotic nondisjunction may also occur (5%). Occasionally, trisomy 18 is the result of chromosomal translocation.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Trisomy 18 is almost always lethal. Most studies show that approximately 50% of affected infants die within the first week of life, and only 3% to 10% survive the first year of life. Surgical interventions may improve overall survival in select patients, with approximately 70% of patients surviving after the first surgery in one case series; however, surviving infants have severe mental and physical deficits. The phenotypic features are variable. This disorder is more commonly seen in female fetuses. Hsiao et al. reported clinical features in 31 cases of trisomy 18, which are listed in Table 150.1 .

| Common Clinical Features | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular system | 77 |

| Gastrointestinal system | 75 |

| FACE | |

| 71 |

| 61 |

| 52 |

| 58 |

| 55 |

| 22 |

| 22 |

| 16 |

| MUSCULOSKELETAL | |

| 32 |

| 52 |

| 26 |

| EXTREMITIES | |

| 58 |

| 29 |

| 52 |

| 26 |

| 22 |

| 13 |

| OTHER | |

| 90 |

| 26 |

| 10 |

Imaging Technique and Findings

Ultrasound.

Fetuses with trisomy 18 have a very high rate of structural abnormalities (birth defects), many of which are detectable on prenatal ultrasound (US). The detection rate of trisomy 18 by US ranges from 53% to 100%. With high-resolution US and attention to detail by experienced sonographers or sonologists, achieving a sensitivity of 100% is possible. A 2009 systematic review and metaanalysis concluded that the accuracy of a genetic US scan for detection of trisomy 18 was 86%. The authors reported that a normal genetic US scan reduces a patient’s risk by almost 90%. This information also helps patients make decisions regarding invasive testing. These findings illustrate the importance of completing the anatomic survey as recommended by the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology.

The gestational age range at which the genetic US scan is performed plays a role in its sensitivity. Bronsteen et al. performed a retrospective chart review of 49 fetuses with trisomy 18 and found that anomaly detection increased from 67% at 15 to 16 weeks’ gestation to 100% at 19 to 24 weeks’ gestation. The number of anomalies found in trisomy 18 also increased from an average of 2.8 at 15 to 16 weeks’ gestation to 4 with advancing gestational age. Early menstrual age, fetal position at the time of US scanning, and maternal body habitus may also affect the accuracy of a genetic US scan.

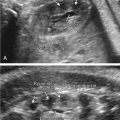

Abnormalities can be classified into major structural anomalies and minor anomalies including soft markers. Major structural anomalies associated with trisomy 18 include cardiac, central nervous system (CNS), gastrointestinal, genitourinary, hydrops, and cystic hygroma. Minor anomalies can be divided into limb and facial anomalies, clenched hands ( Fig. 150.1 ), nuchal fold thickness greater than 6 mm, short limbs (less than the 10th percentile), pyelectasis, echogenic bowel, echogenic intracardiac focus, choroid plexus cyst, and single umbilical artery. Different studies report varying incidence of these anomalies in fetuses with trisomy 18.