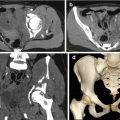

Fig. 6.1

(a) Longitudinal US view of the left shoulder of an 8-year-old girl performed for acute humeral pain shows an irregularity of the cortical aspect of the proximal humerus. (b) Anteroposterior view shows a fracture of the proximal physis, which accounts for the longitudinal growth of the humerus

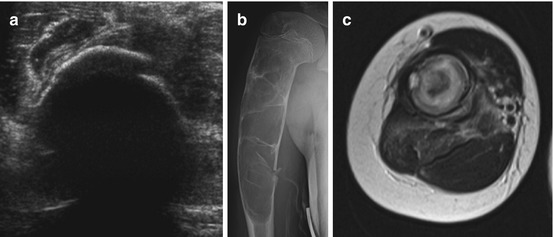

The addition of several imaging modalities can be useful also for the diagnosis of preexisting pathologies (Fig. 6.2).

Fig. 6.2

A young female patient with a history of a known juvenile bone cyst presenting with acute pain after a fall. (a) US shows irregularity of the cortical zone. (b) Anteroposterior view of the right shoulder confirmed the cyst rupture with cortical interruption. (c) Axial T2-weighted image highlights the presence of a double-density fluid-level lesion within the bone, associated with an inhomogeneous intensity of adjacent soft tissue, appearing edematous and inflamed

Traumatic glenohumeral dislocations usually occur in collision sports, such as football and hockey. It is a disorder of the growing-up age, and about 40 % of these occur in patients under the age of 22, although it is uncommon in younger children, with only 1.6 % seen in patients under the age of 10 years [3, 4].

Recurrent dislocation and glenohumeral instability are common after a first-time dislocation and have the highest incidence in patients with open physis.

Most glenohumeral dislocations are anterior with the humerus abducted and externally rotated at the time of the impact with anteroinferior aspect of the humeral head.

The labro-ligamentous complex can be avulsed from the glenoid (classic Bankart lesion) with or without disruption (distacco) of the adjacent scapular periosteum or with bony glenoid fracture (bony Bankart).

The impact of the posterolateral aspect of the humeral head may create a visible depression in the humeral head (Hill-Sachs defect), seen in 38–90 % of patients [5].

In patients with recurrent instability, a more detailed imaging is mandatory.

A great deal of soft tissue capsulolabral injuries associated with acute or chronic recurrent dislocations or instability and diagnosis is best provided by MRI.

Many authors agree that MR arthrography is the most accurate technique, with the greatest efficacy in the younger, athletic population [8, 9] and an overall sensitivity of 91 % for the detection of labral pathology.

HAGL lesion (humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament) is very important to recognize on MRI; the anterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament is torn from its humeral neck attachment and can be seen on MRI as a “J” sign.

About two-thirds of HAGL lesions are associated with other shoulder pathologies, such as labral tears, rotator cuff tears, and Hill-Sachs alterations [10, 11].

Failure to recognize these types of lesions leads to recurrent instability; MR diagnosis is important in surgical planning [11].

Ultrasound has a poor indication in cases of instability; therefore, in these cases, it can be useful in the assessment of fluid collection or indirect signs of instability at the level of the long head of the biceps, the glenohumeral ligament, or the acromioclavicular joint.

Posterior dislocation is less common, and it usually occurs with an axial loading of an adducted internally rotated arm, violent muscle contraction, or posterior glenoid deficiency, as occurs in brachial plexus palsy [12].

MRI is usually performed in order to evaluate the presence of a posterior labral tear, a capsular rent, a “reverse” Hill-Sachs, or an abnormal glenoid version [13, 14].

Superior labral anterior to posterior (SLAP) tears occurring in children are due to microtrauma associated with overhead throwing or are traumatic. In throwers, they are caused by the increased external rotation during the cocking phase, producing enormous torsional stresses at the biceps anchor and the superior labrum causing the detachment of the labrum medially, over the corner of the glenoid.

Another cause of SLAP tears in throwers is the internal impingement; it occurs when the arm is abducted and externally rotated, as we have in the cocking phase, leading to repetitive contact between the humeral and the posterosuperior aspect of the glenoid.

In addition may be those traumas producing traction or compression on the biceps anchor, such as a fall onto an outstretched arm [15, 16].

MRI is mandatory in SLAP tears when surgery is planned; typical MR findings consist of rotator cuff tears, anterior and posterior labral tears, paralabral cysts, and chondral injuries.

MRI can recognize the normal variants of the anterior labrum: the superior sublabral recess, the sublabral foramen, and the Buford complex [17].

MRI can recognize the presence of a paralabral or spinoglenoid notch cyst, associated with persistent symptoms and failure of nonoperative treatment in children with SLAP tears, or compression of the suprascapular nerve and denervation of the infraspinatus [18].

6.2.3 Shoulder: Chronic Repetitive Trauma

Repetitive stress is the leading cause of shoulder injuries in younger athletes. Most of them are observed during the mid to the late teen years, due to the increase of stress forces applied to muscular structures in this age group. These particular conditions have been often observed in baseball players but also in football, swimming, tennis, and all those sports requiring an overhead activity [19].

Little leaguer’s shoulder is a descriptive term used to refer to a stress-related injury of the proximal humeral physis, characterized by the epiphysiolysis of the proximal humeral growth plate.

It usually occurs in 11- to 16-year-olds, presenting with dominant arm shoulder pain aggravated by throwing and tenderness to palpation.

This condition affects those athletes who frequently repeat the action of overhead throwing, such as baseball players, track-and-field athletes, only later volleyball players, tennis players, and swimmers. It is a benign and self-limited condition responding well to conservative treatment [20].

It is characterized by the widening and irregularity of the proximal humeral physis, easily detectable both on x-ray and MRI, which can also highlight the logistic aspect as an area of high signal intensity on T2-weighted images [21].

Rotator cuff injuries are rare in children because the rotator cuff in young patients is more elastic and stronger, without the degenerative changes observed in the elderly population.

They usually occur as tendonitis or strain in response to repetitive microtrauma caused by overhead arm motion.

Primary impingement can occur as a result of a tight coracoacromial arch or simple overuse.

With repetitive stress, the muscle becomes weaker and rotator cuff impingement can result from a multidirectional instability.

These injuries are the major indicators for an ultrasound examination.

They can be classified as complete, incomplete, or partial (sensitivity: 91 %) [9].

Complete lesions extend over the whole thickness from the articular side to the bursal one, presenting hypo-anechoic focal areas with evidence of joint effusion within the coracoid and axillary recesses or in the anatomical locations of tendons. In complete rupture, the tendon is no longer recognizable and tucked beneath the coracoacromial arch.

Other described signs are the double cortex sign, the sagging peribursal fat sign, compressibility, and muscle atrophy.

A partial lesion is characterized by a hypo-anechoic area with poorly defined margins affecting only the articular or bursal portion of the tendon.

However, there is a spectrum of non-rotator cuff abnormalities that are amenable to US examination, including the instability of the biceps tendon, glenohumeral joint, and acromioclavicular joint; arthropathies and bursitis (inflammatory diseases, degenerative and infiltrative disorders, infections); nerve entrapment syndromes; and space-occupying lesions.

MRI is the modality of choice for the evaluation of rotator cuff tears.

When a tendinopathy occurs, it is easy to see an intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted images within the tendon.

A full-thickness tear appears as a hyperintensity on T2-weighted images extending completely through the tendon. A complete tear disrupts the tendon completely, with musculotendinous retraction and a possible upward subluxation of the humeral head.

A partial-thickness tear may present both on the articular and bursal surface and appears as a hyperintensity on T2-weighted images extending through the tendon thickness, superiorly or inferiorly [23, 24].

A rim-rent tear is a partial articular tear of the insertional fibers of the rotator cuff at the greater tuberosity; it is considered as a form of partial rotator cuff tear, and it may involve both the supraspinatus and infraspinatus insertion. If left untreated, it may progress to a full-thickness tear [25].

Subscapularis tendon tears are less common and are frequently associated with biceps tendon abnormalities.

Internal impingement is characterized by the entrapment of the undersurface of the posterior supraspinatus tendon or anterior infraspinatus tendon between the humeral head and posterior glenoid. Undersurface tears of one or both tendons with cystic changes in the posterior humeral head and posterosuperior labral pathology are diagnostic for internal impingement [26].

In conclusion, once adequate radiographs have been obtained to exclude apparent bone disorders, high-resolution US should be the first-line imaging modality in the assessment of non-rotator cuff disorders, assuming the study is performed with high-end equipment by an experienced examiner. More costly and invasive modalities such as MR imaging and MR arthrography should be reserved for bone marrow evaluation and preoperative assessment.

6.2.4 Elbow: Acute Injuries

Pediatric elbow joint trauma is challenging and particularly complex mainly because of the complex anatomy and the presence of several growth plates appearing in different phases of the growing process.

In children, elbow trauma may lead to bony, cartilaginous, or soft tissue injury.

In most of cases, basic radiographs compared with the injured elbow can allow a complete evaluation of injuries, such as joint effusions or fractures, identifying injuries that require surgical intervention, obviating the need for multiplanar imaging.

A careful assessment of soft tissues can provide information about the presence of a possible fracture, because it is frequently associated with the presence of joint effusion.

In the L-L radiogram, when effusion is present, the “fat-pad sign,” reported in 1954, will appear both anteriorly and posteriorly to the third distal aspect of the humerus.

When an anterior conspicuous dislocation of the fat pad is observed, it will result in the classic “sign of the sail,” which is very important because about 90 % of young patients with these radiographic features have a fracture of the elbow. The posterior humeral fat pad is not visible on a normal elbow and becomes visible in the presence of joint effusion.

However, x-ray does not show bone bruising or cartilaginous or soft tissue injury and may underestimate physeal injury, as demonstrated by Beltran and Rosenberg [27] who reported, in a study comprising of eight patients with elbow fractures, that two children had unsuspected transphyseal fracture extension through the unossified epiphyseal cartilage shown by MR imaging.

Carey et al. [28] reported that in 14 suspected physeal injuries, MRI changed the radiographic diagnosis in 50 % of the cases by showing either radiographically occult fractures or unsuspected transphyseal extension. MR findings resulted in a change of treatment in 36 % of the cases.

MRI can improve the understanding of complex trauma; confirm the presence of an occult fracture suggested just by a joint effusion on x-ray; show the condition of the surrounding musculotendinous structures, such as the insertion of biceps muscle upon the radial tuberosity; and evaluate the ulnar nerve, because of its path posteriorly around the medial epicondyle.

In fact, as demonstrated by Major and Crawford, MRI highlighted marrow edema and missed fractures in 13 patients whose initial posttraumatic elbow showed just a joint effusion without fracture [29].

In children of less than 2 years, before the mineralization of secondary growth plates, bony landmarks are not present, limiting the accuracy of x-rays. On the contrary, MRI may easily visualize the unossified growth plate and the cartilage, providing a good contrast between joint fluid, cartilage, and ossified bone [30].

The joint is well assessed by ultrasound which allows the evaluation of tendons, ligaments, muscles, and neurovascular components.

It also allows the assessment of any intra-articular body and the search for any incomplete fracturative lesion where painful swelling is visible.

Pediatric elbow injuries are commonly classified as lateral compression, medial tension overload, and extension overload depending on the mechanism of injury.

They typically occur during the acceleration phase of the throwing cycle when enormous forces are applied on the elbow joint.

In fact, during this phase, compressive forces are applied laterally, across the radiocapitellar joint; tensile forces are exerted medially across the ulnar collateral ligament and flexor/pronator muscle group; posterior tensile forces are applied as the triceps muscle contracts; and impaction forces are exerted as the olecranon extends into the olecranon fossa [31].

Some authors described that about 17–20 % of baseball pitchers between 9 and 15 years of age experience elbow pain during their careers. The incidence of elbow injuries is directly correlated with pitching frequency and is higher for pitchers who throw with poor technique [32–34].

Acute elbow injuries in the pediatric age are not only a characteristic of sports activities; they often occur because of a fall onto an outstretched hand, seen within or outside the sports field.

Medial epicondylar avulsion fracture: It is common (12 % overall) and sometimes associated with the alteration of normal articular relations; they are classified into two types by Woods.

It often occurs among baseball pitchers (7–15 years old) as the medial epicondyle begins to fuse. It is the result of a violent valgus force exerted on the elbow during overhead throwing with a contemporary contraction of the flexor/pronator muscle group.

Radiography is often diagnostic, although US and MRI might be useful when we have an avulsed fracture fragment difficult to see on x-rays [35].

Ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) lesion: In an older adolescent with a fused epicondyle, the UCL may be torn, partially (involving the deep intracapsular layer of the anterior bundle) or completely (more common, involving the midsubstance of the anterior bundle) [36].

It is an uncommon injury and US and MRI can easily depict this kind of lesion.

On T2-weighted MRI sequences, a disruption of the ligament and wave aspect of the fibers and increased intensity can be noticed.

However, the radiologist must be careful about the interpretation of the high signal intensity at the origin of the ligament, because a mild increase of T2 signal intensity at the origin is normal also in the immature skeleton.

Partial tears occur at the ulnar insertion, and in this case, MRI shows the “T” sign, which is the high signal intensity at the distal site of the ligament.

Tendon lesions: They most commonly occur at the distal side of the biceps and at the insertion site of the triceps.

Biceps lesions typically occur during the teenage phase, and they are commonly due to a lift effort; they are well depicted by both US and MRI.

US evaluation can be challenging because of its complex anatomy.

It is important to evaluate also the contralateral elbow and to perform the dynamic tests.

The distal biceps tendon has no tendon sheath that lies in the anterior compartment of the elbow, superficial to the brachialis muscle. Its tendon passes through the antecubital fossa to insert on the radial tuberosity.

Ultrasound examination shows thickening of the tendon fibers, muscle retraction, and the presence of blood infarction.

6.2.5 Elbow: Chronic Repetitive Trauma

During school age, the shoulder, elbow, and wrist can be susceptible to many sports-related overuse injuries.

Little leaguer’s elbow: It is a term used to describe those injuries which affect the medial, lateral, and posterior compartments of the elbow of throwers and gymnasts, in which the “primum movens” is the repetitive valgus overload [39].

Classic little leaguer’s elbow: During childhood and adolescence, the weakest site is the medial epicondyle physis, where chronic and repeated stress, aged by the common tendon of the flexor/pronator muscles and the ulnar collateral ligament, results in the irritation of the physeal cartilage. When it becomes chronic, it is easily detectable by the widening of the medial epicondyle physis, irregularity of the margins, and, eventually, sclerosis and fragmentation [40].

The most common radiographic manifestations are displacement and fragmentation of the medial epicondyle apophysis, although plain film can be normal in up to 85 % of cases.

US and MRI are very useful, especially in those cases in which there is a high clinical suspicion but radiographs are normal.

Sonography has a great ability to medial epicondylar fragmentation.

The epicondyle shows a large area of marrow edema, the physis being widened and hyperintense on T2-weighted images; a thickening of common flexor tendon could also be shown.

Panner disease: It is an osteochondral lesion responsible for lateral elbow pain in children.

It is attributed to avascular necrosis of the capitellum and typically affects the dominant elbow of boys aged 5–12 years.

The onset age is younger than that of patients with osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), occurring during the period of active ossification of the capitellar epiphysis [41].

X-ray shows lucency adjacent to the capitellar articular surface with mild surrounding sclerosis. Days later, larger areas of capitellar radiolucency mixed with diffuse sclerotic changes are clearly visible.

MRI is much more sensitive than x-ray in the early detection of Panner disease; in fact, it can demonstrate diffuse capitellar marrow edema. Normalization of capitellar appearance usually occurs within 1–2 years.

Almost all patients affected by Panner disease recover well, with no treatment, and fully reconstitute the normal architecture of the capitellum.

Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) of the capitellum: It typically occurs in older adolescents aged 11–15 years, when the capitellar epiphysis is almost completely ossified. It consists of a fragment of the capitellum separated or isolated from the surrounding bone. The cause is still unclear, but many authors suggest that it could be a combination of repetitive microtrauma across the radiocapitellar joint and the mild blood supply of the capitellum [41].

Baseball players and gymnasts are often affected by this condition, perhaps because of distraction forces across the medial elbow producing tension forces across the lateral joint.

OCD begins on the anterolateral aspect of the capitellum as a mild subchondral lucency, while Panner disease involves the entire ossification center.

Later on, there is an increasing process of lytic and sclerotic changes with the flattening and fragmentation of the capitellum. Advanced aspects of OCD are characterized by loose body formation, expansion of the radial head, and osteophyte formation.

Sonography is very sensitive to detect OCD capitellar fragmentation.

MRI spectrum of OCD is more severe than that of Panner disease, including abnormal marrow signal, cystic changes, cartilaginous defects, fragmentation, and intra-articular loose bodies.

Two patterns of OCD presentation have been described: one pattern shows a low-signal-intensity ring surrounded by an intermediate area on T1-weighted sequences; the inner portion of the ring is hyperintense on T2-weighted images. The second pattern is characterized by a segmental area of hypointensity on T1-weighted images, which is hyperintensity on T2-weighted ones.

The use of MRI arthrography with gadolinium improves the staging of osteochondral lesions; in fact, in unstable lesions, we observe some fluid or contrast agent encircling the fragment or a cystic lesion under the fragment on T2-weighted images.

MRI not only makes diagnosis and evaluates its extension and the possible presence of displaced fragments, but it can also assist with the evaluation of the stability of the lesion.

Stable lesions have a focus of low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images in a portion of the anterior capitellum.

MR instability criteria are a rim of high T2 signal intensity around the lesion, disruption of the subchondral bone plate, cartilage cracks around the lesion and cysts inside it, or displaced fragments [41].

The presence of intra-articular contrast material around the lesion suggests disruption of the articular surface, indicating the instability of the lesion.

Post-contrast MRI can also be used in order to evaluate patients affected by OCD. The use of i.v. gadolinium contrast may help assess the stability and viability of the lesion. In fact, enhancement of the lesion suggests that it is viable and with good blood supply. On the other hand, the presence of a ring of diffuse enhancement between the OCD lesion and adjacent subchondral bone might represent granulation tissue, indicating that the lesion is unstable.

The last component is the posterior elbow involvement. In fact, during throwing or tumbling, the triceps may impute strong traction on the olecranon, known as “extension overload,” in which the first site affected is the olecranon physis. This condition is characterized by apophyseal widening, irregularity, and delayed closure.

6.2.6 Wrist and Hand: Acute Injuries

Plain film radiographs can provide a detailed evaluation of bone injuries, the degree of radial foreshortening, abnormalities or angulation of the distal radius, possible ulnar fracture or dislocation, and so on.

However, MRI allows additional evaluation of soft tissue supporting structures, especially the intercarpal ligaments and the triangular fibrocartilage (TFC).

TFC tears may occur not only as a long-term result of gymnast wrist or positive ulnar variance but also acutely. In younger athletes, traumatic injuries with respect to the degenerative ones are most common [42, 43].

TFC tears can be a partial-thickness defect or complete perforation through the entire thickness of the disk and can affect both the central (radial) side and the peripheral (ulnar) side. This distinction is important because it affects the treatment; in fact, tears of the ulnar side are repaired because of the rich vascular supply, while central tears are debrided [44].

Clinically, they manifest with ulnar-side wrist pain and a palpable click, associated also with swelling and loss of grip strength.

At MRI, a partial tear is characterized by an irregular or linear surface defect, whereas a complete tear or perforation shows a hyperintense linear abnormality on T2-weighted images. MR arthrography increases MR sensitivity in detecting TFC tears [45].

There is not a great deal of formal studies about the scapholunate tears in the pediatric population, and for this reason, we cannot use the adult upper limit of 2 mm for the normal width of the space between the two bones until the age of 12 [46].

Distal forearm and scaphoid fractures in children often occur from falls onto an outstretched hand.

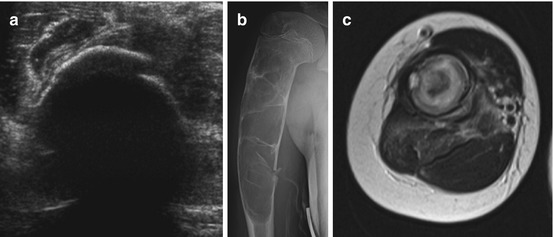

Diagnosis is usually achieved by x-ray, but in some cases, it may be difficult to visualize on plain films, although the fracture is present. In fact, occult scaphoid fractures represent 10–15 % of the whole scaphoid lesions. In these cases, MRI may help to identify an occult scaphoid fracture, showing areas of high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, especially in those obtained with short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) (Fig. 6.3) [47].

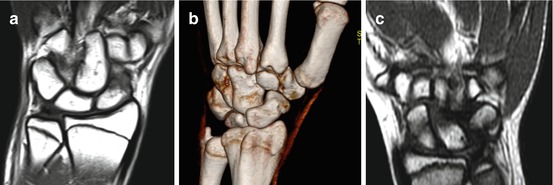

Fig. 6.3

Scaphoid fracture in a 16-year-old-basketball player occurred after a direct blow to the palm. (a) T1-weighted image on the coronal plane shows an inhomogeneous aspect of the distal scaphoid pole, characterized by a diffuse area of low signal intensity, with a subtle fracture within it. (b) VRT reconstruction on the coronal plane shows the irregular presentation of the distal pole, finding suggestive of fracture. (c) Fracture of the body scaphoid, misdiagnosed on plain film in a 10-year-old girl, occurred after a fall onto an outstretched hand. T1-weighted image on coronal plane shows a subtle linear image of low signal intensity at the middle aspect of the bone, suggestive of fracture

US can highlight an irregular aspect of cortical zone which can be misdiagnosed on plain film; it can also show effusion or compartmental hematoma.

Pediatric patients are more likely to suffer from scaphoid tuberosity fracture, which are innocuous unlike scaphoid waist fracture, which may lead to osteonecrosis or nonunion of the proximal pole. Non-displaced waist fracture may appear silent on an initial x-ray; in patients with persistent snuffbox tenderness, MRI can be performed in order to exclude an occult fracture. In this sense, MRI has a 100 % sensitivity for scaphoid fractures, showing a high signal intensity on T2 and a low signal infraction on T1-weighted sequences.

Besides, MRI may also demonstrate marrow edema, and it can also show causes other than fracture, responsible for the patient’s pain, such as osseous and soft tissue contusions and capsular-ligament injuries, clinically known as “dorsal wrist pain.”

US can be defined as the technique of choice in order to search for ligamentous or tendon lesions.

Gamekeeper’s thumb is a common injury in football and basketball players and skiers that occurs following abnormal radially directed force on an abducted thumb. Rupture of the UCL may be total or partial at the distal point of insertion. An avulsion fracture fragment at the ulnar base of the thumb proximal phalanx is typical at the site of UCL attachment. US can show a ligament thickening with an alteration of its normal architecture.

With respect to the contralateral site, it is possible to observe an asymmetrical widening of the first metacarpophalangeal joint on the affected site [48].

MRI is occasionally used to evaluate the soft tissue injury of trigger finger distal avulsion fractures and UCL in patients with a suspected gamekeeper’s thumb prior to surgical intervention.

In some UCL tears, we may have the interposition of the adductor aponeurosis between the torn UCL and the bone, a condition known as “Stener lesion,” which requires surgical intervention.

Mallet finger occurs when there is an abrupt axial load on a partially flexed finger, and it is characterized by the avulsion of the extensor digitorum tendon from the dorsal aspect of the distal phalanx. This avulsion may be tendinous or, more commonly, go with a small bone fragment of the phalanx. It is easily detectable radiographically [49].

If an avulsion fracture occurs on the volar aspect of the distal phalanx, it is termed “jersey finger,” and it develops at the insertion site of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon.

6.2.7 Wrist and Hand: Chronic Injuries

Only a small percentage of young athletes are affected by an overuse condition of the wrist related to wielding rackets, bats, and clubs.

The primary and better known overuse condition of the wrist is the so-called gymnast wrist, more common in female gymnasts, which consists of several conditions affecting the triangular fibrocartilage (TFG) complex tears, interosseous ligament tears, scaphoid stress fractures, ulnar impaction, and ganglion cyst formation.

The repetitive weight bearing on the wrist leads to physeal stress changes of the distal portion of the radius and, sometimes, the ulna. If the injury is stopped, the growth plate may recover itself and the radius may return to normal length; on the contrary, a positive ulnar variance could develop, since the ulna does not undergo the same forces and suffer the same injuries.

The radial physis appears widened, irregular with metaphyseal sclerosis and mild breaking. Later on, the radius appears short due to a delayed growth

MR imaging is more sensitive than x-ray in the detection of physeal changes.

6.3 Lower Limb

6.3.1 Pelvis

Avulsion fractures are common in young athletes aged between 11 and 16 years with a predominance in males.

They usually occur in a “locus minoris resistentiae,” represented by the insertion of the tendons at the level of the apophysis that are secondary ossification centers before the fusion. They are mostly composed by cartilage.

Some biomechanical conditions may determine its detachment, such as excessive lengthening or eccentric contraction, especially in subjects with an imbalance of muscle groups.

The biomechanics of these lesions are the same as those in adults, and they are due to a high degree of muscle injuries generally at the myotendinous junction.

X-ray of the pelvis is usually sufficient for the diagnosis and to assess the extent of the lesion.

Ultrasonography is useful when it is difficult to diagnose the radiological extent of the damage in the growth plate.

The sonographic appearance is characterized by an irregular profile, with a modification of the normal echogenicity and a possible hematoma.

MRI examination (and in some cases CT) may be indicated in more complex cases, with the advantage of being able to explore deep parts poorly evaluated by ultrasound.

MRI is a very helpful technique because it can further characterize the injury by showing the bone edema on T2-weighted and STIR images and the focal extension into the unmineralized cartilage [49].

In the bone pelvis, avulsion can occur in different sites [50].

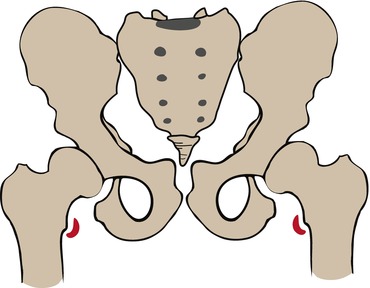

The anterior superior iliac spine is the proximal insertion site of the sartorius and the tensor fascia lata muscle (Fig. 6.4).

Fig. 6.4

Superior iliac spine (Courtesy of Paola Valori)

Sartorius lesion is common in runners, where athletic effort consists of a forced extension of the hip during knee flexion.

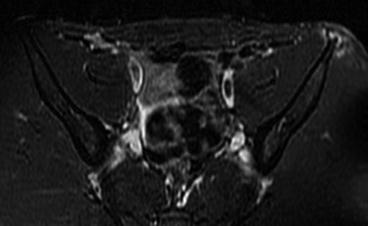

The diagnosis is clinical, but x-ray examination, essential to assess the avulsion extent, can be integrated with a comparative ultrasound examination and with MRI (Fig. 6.5).

Fig. 6.5

Axial STIR image performed in a 13-year-old football player with pelvic pain occurring after a forced hip hyperextension during running. MRI shows a focal area of high signal intensity of the anterior superior iliac spine, indicating apophysitis

The growth plate of the anterior inferior iliac spine appears between 9 and 13 years, welding around 17 years (Fig. 6.6).

Fig. 6.6

Inferior iliac spine (Courtesy of Paola Valori)

At this level, the direct tendon of the anterior rectus muscle of the thigh inserts and its action consists of extending the leg on the thigh and flexing the thigh on the pelvis. The lesion may occur in some sports such as football or rugby, due to a strong contraction against a resistance.

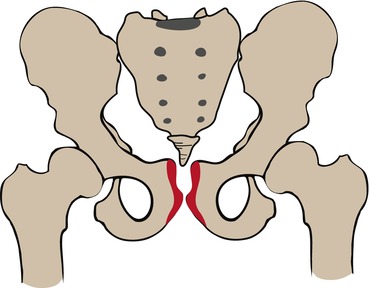

On the other hand, avulsion fractures at the level of the pubic symphysis, where we find the insertion of the adductor muscles, gracilis, and abdominal recti, are rare because they are more often caused by repetitive microtrauma and supported by some anatomical conditions such as asymmetry of the lower limbs [54] (Fig. 6.7).

Fig. 6.7

Level of the pubic symphysis (Courtesy of Paola Valori)

Ultrasound allows to detect the presence of morphological alterations at the site of tendon insertion.

In these cases, MRI is necessary to study the functional myotendinous unit and bone and cartilaginous components and in particular to search for the “stress response” typically associated with these conditions.

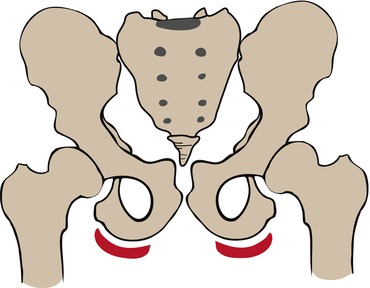

The most common anatomical location of pelvis avulsion fractures is the growth plate of the ischial tuberosity (Fig. 6.8), site of insertion of semimembranosus tendons and hamstrings (composed by semitendinosus and long head of the biceps femoris), characterized by its typical lunate morphology [55] (Fig. 6.9).

Fig. 6.8

Greater tuberosity (Courtesy of Paola Valori)

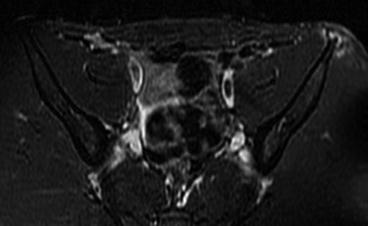

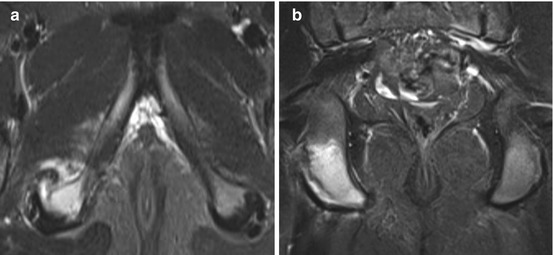

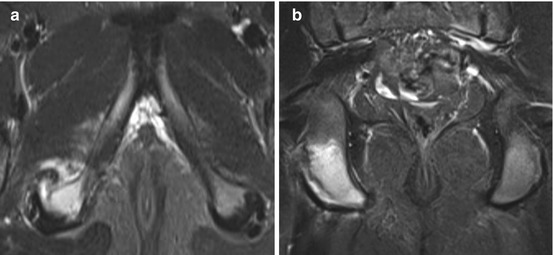

Fig. 6.9

MRI performed in a 12-year-old soccer player. Axial (a) and coronal (b) STIR images show increased marrow signal of the ischial tuberosity with surrounding periosteal edema and teno-periosteal detachment

The treatment of these injuries is generally conservative, but we have to remember that in some significant (>2 cm) dislocations, the outcome may be disabling.

MRI is a very useful to assess the degree of soft tissue involvement, to define whether the injury is complete or incomplete, and to assess the relationship with the sciatic nerve.

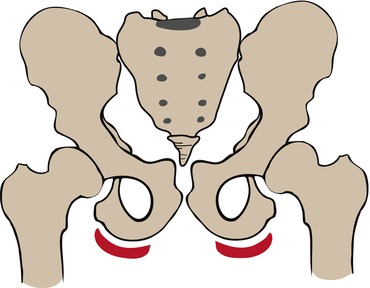

Avulsions at the iliopsoas insertion on the lesser tuberosity of the femur (Fig. 6.10) or of gluteus or tensor fascia lata muscles at the level of the greater trochanter (Fig. 6.11) are very rare [56].