Use of Ultrasound in the Undifferentiated Hypotensive Patient

Care of the undifferentiated hypotensive patient is a challenge for clinicians, and identifying life-threatening conditions that are readily reversible is a priority. Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has had a prominent role over the past 20 years in the care of these patients. Focus on conditions that require emergent intervention, such as pneumothorax, intraabdominal hemorrhage, and pericardial effusion, has been an important addition to resuscitation practice.

The first description of a POCUS examination for the undifferentiated hypotensive patient was described by Rose et al. This examination protocol involves a focused three-view assessment evaluating for abdominal free fluid, pericardial fluid and cardiac activity, and abdominal aortic aneurysm. Subsequent protocols include additional views. The rapid ultrasound for shock and hypotension (RUSH) examination introduced a multipoint ultrasound (US) examination that includes detailed evaluation of the chest and abdomen to assess for causes of shock. Several other protocols have also emerged with varying numbers of US views. Regardless of the specific protocol involved, each of these protocols focuses on the use of US to rapidly identify etiologies of hypotension, with particular attention to conditions that require emergent intervention. Whether the shock is due to a cardiogenic etiology, an obstructive etiology, hypovolemia, or a distributive cause, an organized scanning protocol will narrow the differential diagnosis. The progress and sophistication in POCUS examinations allow detailed evaluation of the hypotensive patient.

The Heart

A focused cardiac US is central to all of the described protocols for US evaluation of the hypotensive patient. The techniques to perform focused echocardiography are explained in the echocardiography chapters.

The initial phase of resuscitation requires estimation of cardiac function, particularly left ventricular ejection fraction. Qualitatively evaluating ejection fraction is straightforward for sonographers of all skill levels. Categorization of the ejection fraction is trifold: preserved, moderately depressed, or severely depressed. This rapid estimate guides the resuscitation and determines whether the etiology of the hypotension is primarily cardiogenic.

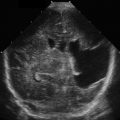

Further interrogation of the heart is performed, depending on the clinical scenario. US is the modality of choice to identify pericardial fluid. This is best evaluated with a substernal or parasternal view. Sonographic characteristics of cardiac tamponade, characterized by right ventricular collapse and alteration of the intraventricular septum, are assessed on the focused cardiac examination. Evaluation of the aortic root is performed when there is suspicion for aortic dissection. With a parasternal long-axis view, an aortic root measurement (no greater than 3.5 cm) can be rapidly evaluated. Other signs of aortic root dissection include pericardial effusion and aortic valve insufficiency. However, these may not be present. Evaluation of the right heart for right heart strain is an important addition to the cardiac examination when massive pulmonary embolus is in the differential diagnosis. This is best assessed with the apical four-chamber view.

The Lungs

The addition of lung US has been an important addition to the POCUS evaluation of the hypotensive patient. The full description of this protocol is outlined in the pulmonary chapters. Originally described by Lichtenstein, the rapid pulmonary assessment provides several important data elements in differentiating types of shock.

Clinicians generally focus on two aspects of pulmonary US in the evaluation of the hypotensive patient. First is the identification of a pneumothorax. US accurately identifies pneumothoraxes. The determination of whether the pneumothorax is causing hypotension via a tension phenomenon is a clinical decision. The second is the identification of interstitial fluid. A rapid scan of the lungs to determine whether there is interstitial fluid consistent with pulmonary edema versus the absence of interstitial fluid may help the clinician determine whether there is a cardiogenic etiology for the hypotension. The presence of interstitial fluid also guides the fluid resuscitation. Patients with hypotension and pulmonary edema have more complex resuscitation algorithms, whether the primary source of hypotension is cardiogenic or not.

The Abdomen

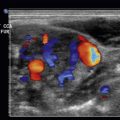

Protocols evaluating for causes of hypotension include abdominal views. Of prime importance is the evaluation for free (intraperitoneal) fluid within the abdominal cavity. It is important to determine if a patient presenting with hypotension has free peritoneal fluid. The etiology of the free fluid requires clinical synthesis of the case. Providers will consider trauma, ruptured ectopic pregnancy, aortic catastrophe, and other less common etiologies. Importantly, US cannot differentiate the type of fluid in the abdomen. This must be considered in evaluating the examination. Given the time-dependent nature of intraperitoneal bleeding, excluding the presence of peritoneal free fluid is of critical importance. Protocols differ as to the number of peritoneal views that are required and may include the right upper quadrant, left upper quadrant, and pelvic views or a single right upper quadrant view. It is important to consider the clinical context of the hypotensive patient. A single right upper quadrant view has been shown to have a very high sensitivity when performed on a hypotensive trauma patient. In addition, the right upper quadrant view is the technically easiest view to reliably obtain. For this reason, this view should be emphasized during the initial US scan of the abdomen in the hypotensive patient.

After a scan for peritoneal free fluid, attention is turned to the vessels of the abdomen. Evaluation of the inferior vena cava (IVC) is an important component of the evaluation of the undifferentiated hypotensive patient. The IVC diameter has been used as a surrogate for intravascular volume status in patients. It is surmised that rapid determination of the IVC diameter, as well as IVC collapsibility, determines the patient’s intravascular volume status. This may help guide fluid resuscitation. The current published validity of this practice is mixed, however. Many factors affect the IVC diameter and collapsibility in addition to intravascular volume status. The IVC diameter is increased by elevated right-sided heart pressure, as seen in cardiac tamponade, pulmonary embolus, and heart failure. The diameter and collapsibility are changed with positive pressure ventilation. Although the IVC assessment has many factors that affect its accuracy, it remains a common component of intravascular volume assessment.

The abdominal aorta is interrogated in patients who present a concern for aortic catastrophe. Upon discovery of an abdominal aortic aneurysm, the clinician must decide based on clinical context if the aneurysm has ruptured, causing hypotension. As the aorta is retroperitoneal, one does not expect intraperitoneal free fluid with a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Size of the aneurysm and the context of the hypotension will contribute to the likelihood of the diagnosis. The presence of an abdominal aortic aneurysm may be the only evidence to suggest a ruptured aortic aneurysm as the cause of hypotension.

Some have described the addition of the femoral vessels to detect deep venous thrombosis as a component of the hypotensive protocol as surrogate markers for pulmonary embolus. In a critically ill patient, this examination may not contribute to narrowing the differential in an emergent fashion.

Putting It All Together

Literature on the practice of undifferentiated hypotensive protocols is limited. A study by Jones et al. demonstrated that the use of a focused protocol of US to evaluate a hypotensive patient narrows the differential during the initial resuscitative phase. During emergency resuscitation, many important practices are utilized to exclude readily reversible causes of hypotension. The practice of POCUS evaluation of the hypotensive patient provides important data to rapidly determine the cause of the hypotension. Practitioners of POCUS must practice a clinically focused US evaluation of a hypotensive patient, rather than merely performing the prescribed views of any specific protocol. Rapidly identifying uncommon but reversible etiologies is paramount when dealing with the critically ill hypotensive patient ( Table 14.1 ).

| Protocol | ACES | EGLS | Elmer /Noble | Falls | Fate | Pocus | Rush: Pump Tank Pipes | Trinity | UHP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| IVC (inferior vena cava) | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | |||

| Fast A/P FAST | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | |||

| Aorta | 3 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Lungs PTX (pneumothoax) | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 6 | ||||

| Lungs effusion | 5 | 2 | 4 | ||||||

| Lungs edema | 4 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 5 | ||||

| DVT (deep venous thrombosis) | 7 | 8 | |||||||

| Ectopic pregnancy | 8 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree