Ultrasound of Soft Tissue Masses

Introduction

Any mass that is steadily increasing in size warrants urgent investigation.

Deep, large or diffuse lesions are best initially imaged with MRI. Plain radiograph or CT occasionally gives additional useful information with regard to calcification or subtle involvement of the underlying bone. Ultrasound is an effective method for guiding percutaneous biopsy.

The clinician referring a patient with a suspected soft tissue mass is usually asking one or more of the following questions: (a) is there a lesion? (b) where is it? (c) what is it? Ultrasound has been shown to be a highly sensitive technique in the detection of soft tissue masses. A normal ultrasound examination excludes a soft tissue mass with a high degree of certainty. Although not often helpful in making a precise diagnosis, ultrasound can readily differentiate solid from cystic lesions. Purely cystic lesions are benign whereas a minority of solid or mixed lesions may turn out to be malignant. Other ultrasound features such as lesion morphology, calcification, compressibility, the presence and type of vascularity and the pattern of internal echoes can all help to narrow the differential diagnosis. MRI will provide additional information with regard to tissue type in lipomatous lesions, fibrous lesions and those containing haemosiderin or other blood products. Cysts rarely require biopsy but are often subjected to ultrasound-guided aspiration. Small superficial solid lesions are suitable for excisional biopsy. Larger or deeper lesions require staging with MRI and, in most cases, preoperative biopsy, which can be performed under ultrasound control. Although ultrasound is generally nonspecific, a confident diagnosis can commonly be obtained by taking into consideration the clinical features along with the ultrasound appearances. This chapter covers the role of ultrasound in the assessment of soft tissue masses with emphasis on those conditions which exhibit specific ultrasound features.

Lipomatous Tumours

Superficial Lipomatous Tumours

The lesion may rarely exhibit acoustic enhancement. Lipoma size is very variable and lesions over 5 cm may be seen, commonly around the shoulder (Fig. 31.2). The reflectivity is variable and depends, in part, on the site of the lesion. Lesions of the head and neck have been described as being typically hyperechoic, whereas those in the extremities tend to be more variable (Fig. 31.3). Doppler signal is occasionally detectable. Lipomas may have an identical echo structure to the surrounding normal subcutaneous fat and the lesion may then be difficult to perceive on ultrasound.

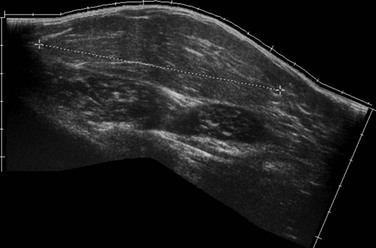

Figure 31.2 Large subcutaneous lipoma. The lesion measures nearly 10 cm in length but there are no sinister features.

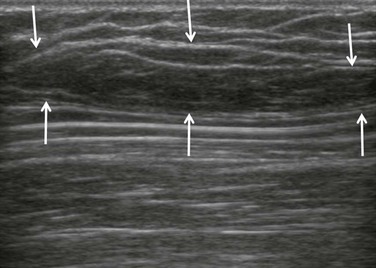

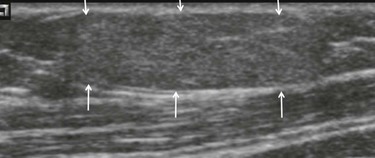

Figure 31.3 Subcutaneous lipoma. The lesion (arrows) contains minor striations and is slightly hyperechoic when compared to the adjacent fat.

One can still make a confident diagnosis of a lipoma when there is a palpable superficial mass and no apparent underlying abnormality on ultrasound.

Although superficial liposarcomas are rare, further imaging and biopsy are required if there are suspicious features such as excessive vascularity or rapid growth. Although large benign lesions are quite common, lesions over 5 cm are often subjected to further imaging as a precaution. Superficial atypical lipoma (previously known as low grade liposarcoma) are occasionally encountered within the subcutaneous fat, but are usually located deep to the muscle fascia.

Deep Lipomatous Tumours

Some intramuscular lipomas may have ill-defined borders due to interdigitation of fat with the muscle fibres. This feature is much better demonstrated on MRI and, when present, suggests that the lesion is at the benign end of the spectrum. Most deep lesions are best imaged with MRI. Deep-seated lipomas and atypical lipomas (previous known as well-differentiated liposarcomas) may have similar ultrasound features and MRI is therefore indicated. Although the detection of nonfatty tissue on MRI implies that the lesion is not a simple lipoma atypical lipoma may also suppress entirely on fat suppression sequences.

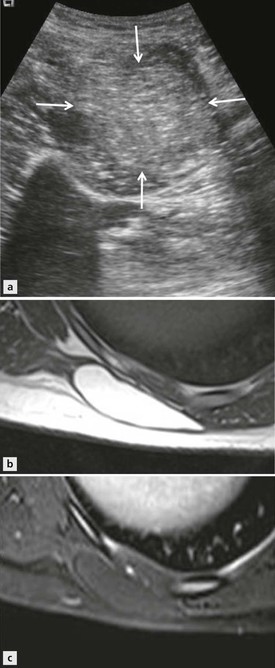

Figure 31.4 Deep lipoma. (A) An intramuscular lipoma is seen as a uniform hyperechoic lesion (arrows). (B) T1-weighted and (C) proton density fat suppression axial images through the chest wall in a different case. The lipoma is seen to lie deep within the muscle. The lesion shows uniform signal suppression on the fat suppresses sequence.

Nearly all liposarcomas of the extremities lie deep to the superficial muscle fascia. The term liposarcoma covers a range of tumours with varying histological and imaging features. The incidence peaks in the sixth and seventh decade and the thigh is the commonest site. Well-differentiated liposarcoma is now termed atypical lipoma; it is at the most benign end of the spectrum and is typically hyperechoic relative to adjacent muscle (Fig. 31.5). The lesion has no metastatic potential and the prognosis is excellent if excision is complete. Neglected lesions will continue to grow and are at small risk of dedifferentiating into a higher grade of sarcoma. Myxoid liposarcoma contains numerous lipoblasts and small plexiform vessels in a well-vascularized myxomatous stroma that has a variable fat content. The proportion of myxoid material, lipid-containing tumour and more cellular tumour can vary, giving a spectrum of imaging appearances. Some tumours are almost purely myxoid and give very uniform homogeneous features on imaging. On MRI these lesions are usually homogeneous and, without the benefit of ultrasound or intravenous contrast, could be misinterpreted as representing a cystic lesion.

Figure 31.5 Well-differentiated liposarcoma. Longitudinal scan showing a mainly echogenic lesion. On Doppler imaging the lesion shows modest hypervascularity.

On ultrasound myxoid liposarcoma may resemble a cyst, being uniformly hypoechoic, but on careful examination the internal structure can be detected and internal vascularity can usually be detected.

However, in most cases of myxoid liposarcoma there is also a lipomatous component (Fig. 31.6). Higher-grade liposarcomas such as round cell and pleomorphic types have no specific ultrasound features that will differentiate them from other sarcomas. Tumours are often highly heterogeneous on imaging. The lesion may be composed of large areas of tumour of varying histological grade. The role of ultrasound in these deep-seated lesions is limited as the tissue characteristics and the relationship of the tumour to the surrounding structures are best appreciated on MRI. MRI is a good method for confirming the lipomatous nature of the tumour and provides a good estimate of the grade of tumour and the fact that the goal for all lesions is complete excision.

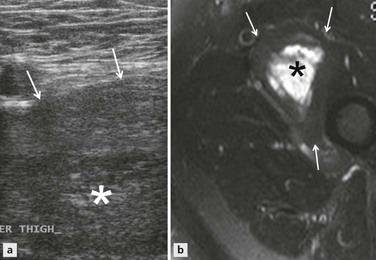

Figure 31.6 Myxoid liposarcoma. (A) The large lesion has a central hypoechoic component (*). Arrows mark the surface of the lesion. (B) Axial STIR MRI shows the lesion consists of a fatty rim (arrows) with a high signal myxoid centre (*).

Muscle Tumours

Lesions in the extremities are usually intramuscular and occur in adolescence. Ultrasound features described in bladder lesions are similar to other types of sarcoma, showing variable echo pattern and cystic areas presumably representing necrosis.

Muscle Hernias and Accessory Muscle

The nature of this lesion is easily determined on dynamic scanning. The herniated muscle is often hypoechoic, presumably due to minor oedema secondary to recurrent herniation (Fig. 31.7). Accessory muscles, such as the accessory soleus at the ankle, may present as a mass and/or a neuropathy due to nerve compression. The true nature of the lesion is readily determined by ultrasound.

Fibrous Tumours

Benign Focal Lesions

Fibromatosis

Palmar and Plantar Fibromatoses

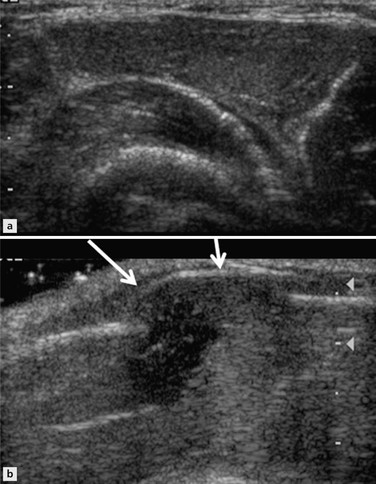

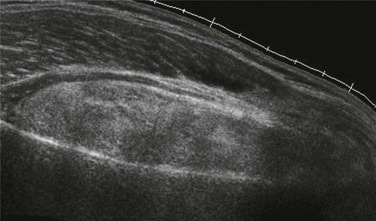

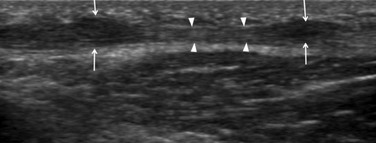

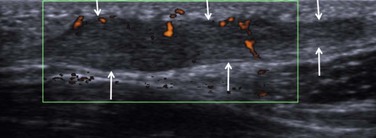

These two conditions result from fibrous proliferation of the fascia. The condition may be bilateral and the plantar and palmar versions may occur in the same patient. In the hand the patient may first notice a single nodule in the palm. Progression is slow and unpredictable. Fibrous cords extend from the lesion to the fingers, giving the characteristic feature of Dupuytren’s disease. Imaging is rarely required. In the plantar version, the patient may present with a lump, pain or both. The nodules may be solitary, multiple and situated either medially or centrally within the fascia. Unlike Dupuytren’s disease the clinical features are less specific and imaging is useful to confirm the relationship of the lesion to the plantar fascia. On ultrasound a typical plantar fibroma is seen as an elongated hypoechoic, nonvascular lesion, which blends into the fascia (Fig. 31.8). A mixed echo pattern can be seen in those lesions larger than 1 cm in length. There is usually no or minimal flow detected on Doppler but the lesion can be vascular (Fig. 31.9).

Figure 31.8 Plantar fibromas. Small hypoechoic lesions (arrows) are seen within the plantar fascia (arrowheads).

Figure 31.9 Plantar fibroma. There is focal widening of the plantar fascia (arrows). Power Doppler demonstrates modest vascularity.

Unlike fibromatosis seen at other sites (as discussed in this chapter), plantar fibromatosis is not aggressive, although recurrence following excision is common.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree