Chapter Outline

Ultrasound Features of the Normal Bowel

Ultrasound Findings of the Abnormal Bowel

Peritoneal, Mesenteric, and Omental Abnormalities

Transabdominal ultrasound (TAUS) allows the hollow viscera to be identified and characterized by anatomic location, morphology, and mesenteric attachments. At higher frequencies, TAUS and endoluminal probes resolve the bowel wall into multiple concentric layers approximating to the histologic strata and usefully referred to as the sonographic gut signature.

This real-time capability, with patient interaction, to correlate symptoms, clinical signs, and imaging findings, makes TAUS a powerful diagnostic tool Since the 1970s, the TAUS features of a broad range of common and uncommon gastrointestinal pathologic conditions have been documented in numerous original publications and review articles.

Ultrasound Features of the Normal Bowel

At higher frequencies (5-17 MHz), the gut signature is comprised of five alternating bands of higher and lower echogenicity equating to serosa (bright), muscularis propria (very dark), submucosa (bright), deep mucosa (dark), and superficial mucosa-lumen interface (bright) ( Fig. 4-1 ). The outer and inner bright bands are very fine and may not be visualized.

Healthy bowel wall is thin (<3 mm), varying with the state of contraction or distention. The muscle layer is the thickest and may be used as a yardstick for assessing relative changes in the mucosa and submucosa.

Ultrasound Findings of the Abnormal Bowel

Bowel Thickening

Thickening of the bowel wall is the most commonly identified pathologic feature. With improving technology, the threshold used to assess pathologic thickening has been lowered, from 5 to 3 mm. As the threshold is lowered, sensitivity increases at the cost of specificity.

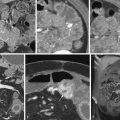

Thickening may be caused by the presence of edema, hemorrhage, inflammation, tumor growth, or infiltration. Any of these may result in the classic ultrasound (US) feature of a hypoechoic circumferential thickening around a strong echogenic center (lumen),variously referred to as the target sign, ring sign, or pseudokidney sign ( Fig. 4-2 ).

For more specific diagnostic indicators, thickened bowel must be characterized as focal or diffuse, circumferential or segmental, and solitary or multifocal. Tumors may grow into the bowel lumen to produce a polyp or polypoid mass ( Fig. 4-3A ) or away from the lumen into the peritoneal cavity (see Fig. 4-3B ).

Bowel Wall Layers

Changes in the gut signature within and adjacent to an observed bowel lesion should be carefully assessed. The high resolution of US provides a unique opportunity to identify the specific bowel layers affected, characterize the lesions, and diagnose the underlying process.

In pathologic conditions, the gut signature may be preserved, exaggerated, distorted, diminished, or obliterated. Focal alterations of the gut signature may allow identification of bowel lesions with borderline thickening ( Fig. 4-4 ).

Bowel Lumen

Commonly, when the bowel wall is thickened, the bowel lumen is compromised, becoming narrowed or strictured. An uncommon exception to this is the aneurysmal dilation seen in lymphomas and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), in which the lumen in the diseased segment enlarges.

Dilation of the bowel lumen is seen proximal to an obstructing lesion, where it is initially accompanied by increased peristalsis. Dilation with no peristalsis may be caused by late-stage obstruction or paralytic ileus, usually seen after abdominal surgery.

Bowel Plasticity, Mobility, and Peristalsis

TAUS resolution permits visualization of peristalsing small bowel folds, particularly as fluid passes along the lumen ( Fig. 4-5A ), and of rigid folds in dilated, fluid-filled obstructed loops ( Fig. 4-5B ). Most disease processes result in stiffening of the affected bowel segment, which is observed sonographically as more rigid, less compressible, less easily displaced, and with reduced or absent peristalsis. Real-time scanning allows for the observation of other motility disorders, such as nonobstructive intussusceptions in celiac disease ( Fig. 4-6 ).

Altered Blood Flow

Doppler signals are negligible in normal bowel wall but assessment of flow in masses or thickened segments is essential. Color and power Doppler signals indicate hyperemia in actively inflamed segments or hypervascular lesions, and the absence of signals in a conspicuously thickened bowel segment may indicate ischemia. Most tumors have sparse Doppler signals but hypervascularity is a significant differentiator and should be routinely assessed (see Fig. 4-3B ).

Extramural and Mesenteric Changes

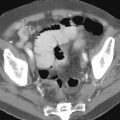

Bowel wall disease may extend to involve peri-intestinal structures, adjacent loops, or solid organs. Around inflammatory bowel lesions, collections, and abscesses, mesenteric fat becomes edematous (swollen and hyperechoic), displacing adjacent structures and increasing the conspicuity of the lesion ( Fig. 4-7 ).

Changes in mesenteric lymph node size, shape (oval, round), echotexture, and surface should be documented. The initial identification of focal mesenteric lymphadenopathy should direct the search for a bowel abnormality.

Ultrasound Technique

TAUS is a well-tolerated, noninvasive technique. A 6-hour fast induces a quiescent intestinal state and reduces bowel gas; no other preparation is required. Focused bowel TAUS is preceded by a general examination of the abdomen and pelvis. Particular attention should be given to deeper recesses inaccessible to the higher frequency probes used for detailed investigation of the bowel wall.

Most bowel pathologic findings displace bowel gas and feces, making them stand out against normal bowel segments. Focal bowel masses, segments of wall thickening, or dilated loops may be apparent, even at lower frequencies, but high-frequency probes are essential to characterize changes in the layers of the bowel wall.

Graded Compression

The term graded compression was introduced by Puylaert to describe the gradual progressive increase in pressure that the operator applies to the probe while making gentle sweeping movements. Done carefully to minimize discomfort, this is an essential technique for bringing the probe closer to the bowel, displacing bowel gas and overlying bowel loops and assessing the compressibility and rigidity of normal and abnormal bowel loops and mesenteric fat.

Mowing the Lawn

Surveying the entire intestine within the abdominal cavity requires a systematic technique. Puylaert recommended the use of overlapping vertical sweeps of a high-frequency probe up and down the abdomen, similar to the motion of a lawnmower. Additional operator techniques include posterior manual compression and scanning in the left lateral decubitus position to assess the retrocecal area.

It is my practice to begin bowel scanning in the left iliac fossa (LIF), where the left colon is easily identified and compressed against the left psoas (see Fig. 4-1 ). This is an opportunity to optimize scanning parameters so that wall layers can be clearly identified, even in briskly peristalsing small bowel segments.

The distribution of bowel in the right iliac fossa (RIF) is variable. Several small bowel loops may be present, and the terminal ileum should only confidently be identified if continuity with the ileocecal valve is demonstrated. Reexamining the right iliac fossa with the patient in a left decubitus position allows movement of the mobile small bowel and cecum into different positions, redistribution of bowel gas, and improved access to a retrocecal appendix.

In adult female patients, transvaginal scanning may give excellent views of low pelvic bowel loops ( Fig. 4-8 ).

Peritoneal, Mesenteric, and Omental Abnormalities

Acute Appendicitis

Acute appendicitis is one of the most common causes of acute abdominal pain and is the most common indication for urgent abdominal surgery. It is more prevalent in older children and young adults.

Appendicitis is the result of luminal obstruction, usually by a fecalith or appendicolith. Less common causes include lymphoid hyperplasia, parasites, and primary and secondary tumors. The obstructed appendix is susceptible to mucosal ischemia and necrosis, which may progress to transmural inflammation, full-thickness infarction, and perforation (in ≈20% of cases).

The intention to preempt complications underpins the practice of early surgical intervention based on clinical assessment and laboratory tests. The “typical” clinical presentation is of vague central or epigastric abdominal pain with anorexia, progressing to nausea and vomiting, followed by migration of the pain to the right lower quadrant, and accompanied by fever, leukocytosis, and rebound tenderness. Any of these features may only be present to a variable degree or absent, so symptoms, signs, and laboratory tests are only moderately accurate for predicting appendicitis.

This strategy persists widely, although between one in three to five removed appendices will be healthy, in spite of over 20 years of evidence of the reduction in the number of unnecessary appendectomies using diagnostic imaging.

Sonography of the Normal Appendix

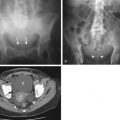

The normal appendix is elusive. It varies greatly in size (average, 8 cm; range, 1-24 cm) and position (pelvic and retrocecal being the most common). With TAUS, the appendix is identified as a thin, blind-ending tube, with a normal gut signature, in continuity with the cecal pole and arising several centimeters from the ileocecal valve.

Sonographic identification of the normal appendix is difficult and often only partial (see Fig. 4-8 ), because overlying loops must be compressed or displaced, and the healthy appendix is often coiled up. Identification rates for the normal appendix, in a population not presenting with suspected appendicitis, varies widely and is related to numerous factors, including technique, operator experience, examination time, and patient body habitus.

Sonography of Acute Appendicitis

The earliest sonographic descriptions of acute appendicitis identified the dominant diagnostic criteria as a noncompressible, blind-ending tube, with a maximum outside diameter (MOD) less than 6 mm. More recent studies have shown normal appendices with diameters of more than 6 mm and lumen distention by feces and/or air, confirming that this threshold diameter is unreliable unless included with other sonographic signs of appendiceal or extra-appendiceal inflammation ( Box 4-1 ). Requiring a combination of these criteria to be present, together with significant clinical evidence of acute appendicitis, reduces the number of false-positive diagnoses ( Fig. 4-9 ).

Noncompressible blind-ending tube

Lumen distention (MOD > 6 mm)

Wall thickness > 3 mm

Loss of gut signature

Hyperemia on Doppler scanning

Hyperechoic periappendiceal fat thickening

Local transducer tenderness

Appendicoliths are frequently identified in asymptomatic patients with otherwise normal US appearances and are not a reliable indicator of inflammation. In focal appendicitis, the MOD may not exceed 6 mm, and the diagnosis may be missed if the entire appendix is not visualized. The perforated appendix is even more elusive but may be most reliably identified by loss of the hyperechoic appendiceal wall layer (indicating transmural inflammation) and loculated periappendiceal or pelvic fluid collections. The negative predictive value of a scan in which the appendix is not identified differs widely across studies but is more reliable when the operator regularly identifies a normal or abnormal appendix.

The strategic place for TAUS in the imaging of acute appendicitis is considered later.

Mimics of Acute Appendicitis

The imaging objectives for patients referred with suspected acute appendicitis are to identify the inflamed appendix or a normal appendix and any other cause of presentation. The most common differentials are acute diverticulitis, gynecologic causes, and mesenteric adenitis (in children), but prospective studies have identified a number of frequent and less frequent mimics ( Box 4-2 ) and documented the relevant TAUS features.