Uterine carcinomas can be divided primarily into endometrial cancer and uterine sarcomas. Cervical cancer is also considered a uterine malignancy but is covered in Chapter 33 .

Endometrial cancer, primarily adenocarcinoma, is now the most common uterine malignancy. Seventy percent to 90% of cancers occur in women over age 50 and present with vaginal bleeding in the vast majority of cases. Most endometrial cancers (80%) are caught early at stage I and are completely curable by hysterectomy. Early diagnosis by tissue sampling and characterization by imaging, primarily transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are critical to diagnosis, treatment planning, and survival.

Uterine sarcomas are rare, constituting 1% to 8% of uterine malignant tumors. They are fast-growing aggressive cancers associated with poor prognosis. These occur most commonly in postmenopausal women. Metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis is common.

Uterine sarcomas most commonly present as an abnormal pelvic mass with abnormal vaginal bleeding or discharge, and pelvic pain. Uterine sarcomas are mesodermal in origin and generally subclassified into four types: malignant mixed müllerian tumors (MMMT), leiomyosarcoma, endometrial stroma sarcoma (low and high grade), and adenosarcoma (considered a subtype of MMMT).

Imaging plays a key role in diagnosing and characterizing uterine malignancy.

Ultrasound (US), particularly TVUS, is the initial examination used to define the endometrium and myometrium. MRI is most reliable for further initial characterization, staging, treatment, and posttreatment follow-up evaluation for uterine malignancy. MRI is also valuable in selecting patients for lymph node sampling or for selection of cases that require specialist gynecology referral. MRI also plays a key role in detection of local disease recurrence after treatment.

The prognosis for women with uterine cancer primarily depends on the extent of disease at diagnosis.

Surgery alone can be curative if the malignancy is contained within the uterus. The value of pelvic radiation therapy is not firmly established. Chemotherapy is indicated in some cases, although overall trials for primary and adjuvant treatment remain lacking with respect to efficacy and survival benefit.

Disease

Definition

Endometrial cancer (adenocarcinoma) is a proliferation of abnormal endometrial cells that line the uterine cavity.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Endometrial carcinoma is common. It is the fourth most common female cancer and the most common malignancy of the female reproductive tract.

The incidence has increased in the United States, presumably because of increased life expectancy and obesity.

Risk factors for endometrial cancer include postmenopausal age, obesity, long exposure to estrogen through supplementation (particularly unopposed estrogen), early menarche, nulliparity, tamoxifen, polycystic ovary syndrome, and other entities that increase the estrogen effect on the endometrial tissue over time. Hypertension and diabetes have also been associated with an increased risk. See Box 32-1 for endometrial cancer risk factors.

- ▪

High levels of estrogen

- ▪

Endometrial hyperplasia

- ▪

Obesity

- ▪

Hypertension

- ▪

Polycystic ovary syndrome

- ▪

Nulliparity (never having carried a pregnancy)

- ▪

Infertility (inability to become pregnant)

- ▪

Early menarche (onset of menstruation)

- ▪

Late menopause (cessation of menstruation)

- ▪

Endometrial polyps or other benign growths of the uterine lining

- ▪

Diabetes

- ▪

Tamoxifen therapy

- ▪

High intake of animal fat

- ▪

Pelvic radiation therapy

- ▪

Breast cancer

- ▪

Ovarian cancer

The 5-year survival rate is between 96% for stage I disease and 25% for stage IV disease. Prognostic factors include stage, depth of myometrial invasion, lymphovascular involvement, nodal status, and tumor histologic grading. See Tables 32-1 and 32-2 and Box 32-2 for endometrial cancer staging and prognosis.

| Primary Tumor (T) | ||

|---|---|---|

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed | |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | |

| T1 | I | Tumor limited to the uterus |

| T1a | IA | Tumor limited to the endometrium/endocervix |

| T1b | IB | Tumor invades less than half of the myometrium |

| T1c | IC | Tumor invades more than half of the myometrium |

| T2 | II | Tumor extends beyond the uterus, within the pelvis |

| T2a | IIA | Tumor involves adnexa |

| T2b | IIB | Tumor involves other pelvic tissues |

| T3 | III * | Tumor involves abdominal tissues |

| T3a | IIIA | One site |

| T3b | IIIB | More than one site |

| T4 | IVA | Tumor invades bladder or rectum |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | ||

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | |

| N1 | IIIC | Regional lymph node metastasis |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | ||

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis | |

| M1 | IVB | Distant metastasis (excluding adnexa, pelvic, and abdominal tissues) |

* In this stage lesions must infiltrate abdominal tissues and not just protrude into the abdominal cavity.

| Primary Tumor (T) | ||

|---|---|---|

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed | |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | |

| Tis * | Carcinoma in situ (preinvasive carcinoma) | |

| T1 | I | Cervical carcinoma confined to corpus uteri |

| T1a | IA | Tumor limited to endometrium or invades less than one half of the myometrium |

| T1b | IB | Tumor invades one half or more of the myometrium |

| T2 | II | Tumor invades stromal connective tissue of the cervix but does not extend beyond uterus † |

| T3a | IIIA | Tumor involves serosa and/or adnexa (direct extension or metastasis) |

| T3b | IIIB | Vaginal involvement (direct extension or metastasis) or parametrial involvement |

| T4 | IVA | Tumor invades bladder mucosa and/or bowel mucosa (bullous edema is not sufficient to classify a tumor as T4) |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | ||

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | |

| N1 | IIIC1 | Regional lymph node metastasis to pelvic lymph nodes |

| N2 | IIIC2 | Regional lymph node metastasis to paraaortic lymph nodes, with or without positive pelvic lymph nodes |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | ||

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis | |

| M1 | IVB | Distant metastasis (includes metastasis to inguinal lymph nodes, intraperitoneal disease, or lung, liver, or bone; it excludes metastasis to paraaortic lymph nodes, vagina, pelvic serosa, or adnexa) |

* FIGO no longer includes stage 0 (Tis).

† Endocervical glandular involvement only should be considered as stage I and not as stage II.

- ▪

75%-95% for stage I

- ▪

50% for stage II

- ▪

30% for stage III

- ▪

<5% for stage IV

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Endometrial cancer arises from abnormal division of endometrial cells and atypical adenomatous hyperplasia, which lead to adenocarcinoma. Less frequently it arises without preceding hyperplasia and presents with poorly differentiated and more aggressive varieties, such as clear cell or papillary serous carcinomas.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Vaginal bleeding in postmenopausal patients is abnormal. It is the most common presenting symptom for endometrial cancer. Endometrial cancer accounts for approximately 10% of the cases of vaginal bleeding in postmenopausal women.

An abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) smear showing tumor cells may be the first indication of endometrial cancer. Unfortunately, the minority of cancers present in this way.

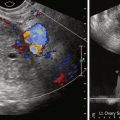

Nearly all endometrial cancer (>95%) is associated with a thickened endometrial stripe defined as greater than 5 mm in postmenopausal women using TVUS.

A postmenopausal woman with bleeding and an endometrial stripe thickness of more than 5 mm should be further evaluated with sonohysterography to look for a focal finding (which might be missed by random endometrial sampling) and endometrial biopsy if warranted.

Endometrial cancer is typically diagnosed with endometrial biopsy or dilatation and curettage, with MRI used to evaluate the extent of disease to aid in surgical and treatment planning.

After treatment for endometrial cancer there is always risk for recurrence. In the vast majority of cases, the recurrence is within the first 3 years after diagnosis and is most common in women with high-grade or high-stage disease. The recurrence rate in low stage I disease is less than 5%. The majority of recurrence is local arising from the vaginal cuff or nearby pelvic structures.

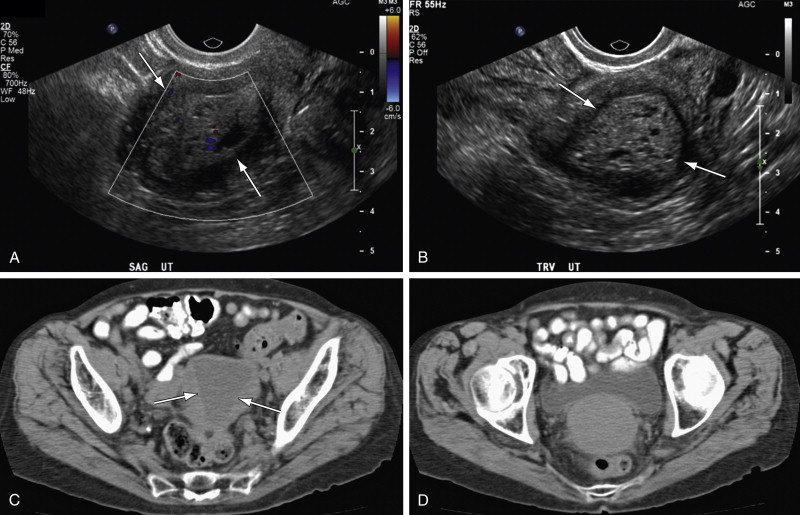

Imaging Indications and Algorithm

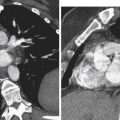

TVUS is the first step in evaluating postmenopausal bleeding. It is not sensitive or specific for the diagnosis of cancer but is sensitive for thickness of the endometrium and for detection of other more common sources of bleeding such as polyps or myomas, especially when coupled with saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS) ( Figures 32-1 through 32-4 ).

SIS is sensitive for detecting focal lesions and improves visualization of the endometrial surface. It can further characterize focal versus diffuse findings on TVUS, as well as further characterize the uterine cavity and endometrial thickness in patients for whom no source of bleeding is identified with TVUS.

There are also easy-to-use, relatively inexpensive devices now available that allow for tissue sampling during sonohysterography, coupling characterization, and tissue diagnosis (Goldstein sonobiopsy catheter; Cook OB/Gyn, Spencer, IN).

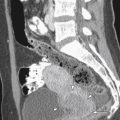

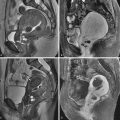

MRI is the study of choice for presurgical treatment planning of endometrial carcinoma because of its excellent soft tissue resolution. The diagnostic challenge that affects treatment planning is the presence and depth of myometrial invasion, cervical stroma invasion, lymph node involvement, and evidence for metastatic spread of disease. Invasion of less than 50% of the myometrium markedly improves prognosis.

Dynamic post–contrast female pelvic MRI has been shown to give superior definition with respect to depth of myometrial invasion compared with T2-weighted imaging.

Sala et al demonstrated that on unenhanced T1-weighted images, endometrial carcinoma is isointense to the normal endometrium. Endometrial cancer can show high signal intensity on T2-weighted sequences but is more typically heterogeneous and may even be of low signal intensity. After intravenous contrast medium administration, the normal inner myometrium shows avid enhancement earlier than the outer myometrium. The maximum contrast between the inner and outer layers of the myometrium occurs at 50 seconds. In general, endometrial cancer enhances earlier than normal endometrium but later than the adjacent myometrium, helping to discriminate small tumors, even those contained by the endometrium.

Imaging Technique and Findings

Ultrasound

Endovaginal US is generally the first diagnostic choice to evaluate the thickness of the endometrial stripe and characterize the nature of the endometrium. Myometrial invasion can also be detected by endovaginal US (although it is not as sensitive as female pelvic MRI) (see Figures 32-1 through 32-4 ).

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) is used to stage the tumor (adenopathy, visceral or osseous involvement). Contrast-enhanced studies are indicated when advanced disease is possible.

Magnetic Resonance

For female pelvic MRI it is optimal to have quiet loops of small bowel to limit motion degradation within the pelvis. This can generally be accomplished by having patients fast 4 to 6 hours before their MRI examination. Alternatively, intravenous glucagon can be used. Emptying the bladder before imaging is also helpful to decrease ghosting and motion artifacts on the T2-weighted sequences. Patients are imaged in the supine position using a pelvic surface array multichannel coil.

The author’s protocol is discussed here. A generic protocol for malignancies can be found in Chapter 5 . Coronal T1-weighted spin echo images with large field of view evaluate the entire pelvis and abdomen for adenopathy and bone marrow change. High-resolution T2-weighted images in the sagittal plane and parallel and perpendicular to the central cavity are completed for primary evaluation. Dynamic contrast-enhanced two- or three-dimensional gradient echo T1-weighted images with a smaller field of view in sagittal and axial oblique views are completed to evaluate the submucosal level and myometrium.

Sagittal and oblique axial multiphase intravenous contrast-enhanced three-dimensional gradient echo T1-weighted fat-saturated sequences through the uterine corpus are used to improve accuracy. The early enhancement phase (0 to 1 minute) allows identification of the subendometrial zone, which enhances earlier than the myometrium and corresponds to the inner junctional zone. Identification in this region helps detect early myometrial invasion because the junctional zone can become indistinct in postmenopausal women. The equilibrium phase (2 to 3 minutes after injection) allows better evaluation of deep myometrium to assess for invasion, and the delayed phase (4 to 5 minutes) enables better evaluation of cervical stroma invasion.

The tumor–myometrium interface should be assessed in at least two planes. The sagittal and perpendicular to uterine corpus are generally most helpful (see Figure 32-2 ).

Positron Emission Tomography–Computed Tomography

Positron emission tomography (PET)-CT is playing an emerging role in staging endometrial cancer. It offers superior identification of pelvic and paraaortic lymph node metastatic deposition and improves treatment management and radiation field determination in those with advanced disease.

Differential Diagnosis

From Clinical Presentation

- •

Hormonal imbalance

- •

Endometrial hypertrophy/hyperplasia and atrophy

- •

Vaginal bleeding from other cause (polyp, submucosal myoma)

- •

Uterine carcinoma/sarcoma

- •

Cervical cancer

From Imaging Findings

- •

Other uterine carcinomas

- •

Endometrial polyps, submucosal and intracavitary myomas

- •

Endometrial hyperplasia

- •

Subendometrial cystic change from tamoxifen

- •

Lymphoma (rare)

Synopsis of Treatment Options

Medical

For stage IA (low risk/low grade) disease, surgery is the treatment of choice and curative (see later discussion). For advanced stage disease, chemotherapy—primarily paclitaxel, cisplatin, and doxorubicin—combined with radiation has a role after surgical removal and/or debulking. Chemotherapy has shown to have a survival benefit beyond that of radiation alone.

Focal pelvic radiation when there is evidence of intermediate- or high-risk tumors has been shown to reduce local recurrence rate (pelvis and vagina). It remains controversial whether vaginal brachytherapy or external beam radiation therapy is preferred, although whole abdominal irradiation has shown some improved outcomes.

Surgical and Interventional

Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is the initial and primary treatment choice. Endometrial cancer often spreads to the ovaries first, and they are generally removed with the fallopian tubes. Lymph node sampling may also be performed. With stage I disease hysterectomy is considered curative.

Reporting: Information for the Referring Physician

Any endometrial stripe thickness >5 mm by vaginal ULS should be reported as potentially abnormal in postmenopausal patients with vaginal bleeding, and sonohysterogram and/or biopsy are recommended if not performed at the same time as the TVUS. Even if the stripe is less than 5 mm, some postmenopausal women will require additional evaluation if bleeding does not respond to hormone replacement therapy.

Disease

Uterine sarcomas, including most malignant mixed müllerian tumors (MMMTs), are also referred to as carcinosarcomas . They have both carcinomatous and sarcomatous elements (adenocarcinoma arising from epithelial elements and sarcoma from stromal elements). Some classify these uterine tumors as metaplastic carcinomas (rather than a subgroup of uterine sarcoma). If MMMTs are excluded as a sarcoma, then leiomyosarcoma would be considered the most common primary uterine sarcoma.

Carcinosarcoma parallels endometrial cancer in its postmenopausal predominance and in other epidemiologic features. This cancer generally occurs in women between 47 and 56 years of age (although the range is 20 to 90 years of age).

The treatment of carcinosarcoma is becoming similar to the combined modality treatment approaches used for endometrial adenocarcinomas.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

MMMT is the most common uterine sarcoma, comprising 2% to 5% of the reported uterine malignancy cases, and accounting for 50% of the reported cases of primary uterine sarcomas. For women with carcinosarcomas, if initial surgical evaluation includes an isthmic or cervical location, lymphovascular space invasion, serous and clear cell histology, or grade II or III, the risk for metastatic disease is high.

Disease recurrence and progression posttreatment is correlated with adnexal spread, lymph node metastases, tumor size, peritoneal cytologic findings, and depth of myometrial invasion. Patients with well-differentiated sarcomatous components or carcinosarcomas have a better prognosis with longer progression-free intervals than those with moderately to poorly differentiated sarcomas. See Table 32-2 and Box 32-3 for uterine sarcoma staging and prognostic factors.

| Primary Tumor (T) | ||

|---|---|---|

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed | |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | |

| T1 | I | Tumor limited to the uterus |

| T1a | IA | Tumor ≤5 cm in greatest dimension |

| T1b | IB | Tumor >5 cm |

| T2 | II | Tumor extends beyond the uterus, within the pelvis |

| T2a | IIA | Tumor involves adnexa |

| T2b | IIB | Tumor involves other pelvic tissues |

| T3 | III * | Tumor infiltrates abdominal tissues |

| T3a | IIIA | One site |

| T3b | IIIB | More than one site |

| T4 | IVA | Tumor invades bladder or rectum |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | ||

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | |

| N1 | IIIC | Regional lymph node metastasis |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | ||

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis | |

| M1 | IVB | Distant metastasis (excluding adnexa, pelvic, and abdominal tissues) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree